Introduction

This course will focus on the key features of autism that distinguish it from other disorders. The reason I suggested this topic is because of the increase in the number of diagnosed cases of autism. Sometimes I'm called into a case where a child has been diagnosed with autism, but it turns out that the child doesn't have autism after all. Therefore, it is important, as I'm sure we would all agree, to get this diagnosis correct.

Speech language pathologists are learning more and more about autism and more commonly being involved in, or is sometimes the primary diagnostician of autism spectrum disorders. As you can see, I think we are uniquely qualified to do that diagnostic very appropriately and accurately, so I hope that you will learn how to participate in diagnosing autism and how to get the diagnosis right.

Is it Autism?

So, is it autism? It is a question that seems to continue to elude us. Autism is a serious medical condition that bestows lifelong issues for individuals with the condition, their family, and their community. Accurate diagnosis is important for the individual, their family, and everybody who cares about them. The diagnostic criteria for autism has changed, but the disorder remains the same as when Leo Kanner identified it in 1943. It's a disorder that evidences itself in the presentation of social, communication, and behavioral symptoms.

There is still no reliable medical test to identify autism and there's no standardized measure that alone can diagnose the condition either. The best method of identifying autism continues to be by observation of skilled professionals who work extensively within the autistic population in collaboration with their families, educators, and medical professionals. Together, we can put the pieces of the puzzle together and render an accurate autism diagnosis. A good place to begin is to understand the diagnostic signs of autism that collectively yield the diagnosis of autism and are either specific to autism or might indicate just one facet of the disorder.

Diagnosticians

Who are the diagnosticians who participate in this process? Autism can be diagnosed by a wide range of professionals including doctors, teachers, educators, and therapists like speech language pathologists. It doesn't have to be any one of these individuals, so it's important to recognize we can play a very important, if not a main role in performing the diagnosis as speech language pathologists.

Who Is Qualified to Assess the Core Features of ASD

Who is qualified to assess the core features of ASD? The core features involve communication, social skills, and behavior. I would argue that the speech language pathologist is the diagnostician of choice for diagnosing autism. As recommended by ASHA, we need to have extensive experience before we take on this role, but if you, as a speech language pathologist, have extensive experience in this population, you may be one of the more qualified diagnosticians on the team. It's important to remember that.

Roles of the SLP: ASD and SCD

In 2006, ASHA came out with a series of papers to delineate more information for speech-language pathologists about autism spectrum disorders. One of those papers delineates the roles and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists in diagnosing and treating autism spectrum disorders.

- Research

- Assessment and Intervention

- Collaboration

- Diagnosis

- Screening

- Advocacy

Even if we do play one of the major roles in the diagnostic procedure, we need to do this in collaboration with other people, including the family members, educators, medical professionals, anyone who's been involved with the child. We can play a role in screening for autism spectrum disorders. There are a number of good screening tools available for assessing the condition and assessing the communicative and social abilities of the child and intervening in those ways as well as making the actual diagnosis. Speech-language pathologists also participate in research relative to autism spectrum disorders and in advocating for these individuals and their families. We can play a role in many ways and I encourage you to consult this 2006 paper from ASHA regarding the many different ways that we can participate.

ASD: New Diagnostic Parameters

Changing Criteria for Diagnosing Autism (APA)

How have the diagnostic criteria changed for autism spectrum disorders? For many years, the diagnostic and statistical manual of the American Psychiatric Association specified a set of diagnostic criteria that are globally used to diagnose the condition. In 2013 they had a major revision of these criteria. As of 2017, there are many individuals with autism spectrum disorder or Asperger's disorder or PDD-NOS who still have those diagnoses and based on the 2013 standards or diagnostic criteria, they keep those diagnoses until they are re-evaluated. There are many different diagnostic terms today and it's important to be aware of the criteria under which individuals were diagnosed and re-diagnosed if they are reassessed in the future.

In 2000, the DSM-4 specified that there were five pervasive developmental disorders. One of those was autistic disorder, or autism, as we more commonly refer to it. It was one of five disorders which were entitled pervasive developmental disorders because they were pervasive into almost every aspect of the individual's life. Autistic disorder was diagnosed by a series of social, behavioral, and communication symptoms that I will discuss shortly.

Asperger's disorder, on the other hand, was differentiated from autism in that the individuals with this condition were very fluent with their language. They most-likely presented some early language delays, but once they learned language they spoke in sentences conversationally in a very fluent way. This very much differentiated it from autistic disorder in which individuals had life-long difficulty putting communication together, even if they achieve conversational language. A lot of times it was still very difficult for them to put their thoughts into words and to think in words.

There were three other pervasive developmental disorders in this category. One was pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified, or PDD-NOS. This turned out to be the most popular category of pervasive developmental disorder. It was intended to be for individuals who exhibited some characteristics of autism, yet not enough characteristics to give the full diagnosis of autistic disorder. The original authors of the DSM-4 intended this to be a placeholder condition when diagnosticians, maybe very early in development, were not sure whether the child was going to present the full autistic disorder or maybe just had a few characteristics that they may develop out of over time. It was really meant to be a placeholder in which a new diagnosis, or a new evaluation, was conducted in a year or so to determine whether or not autistic disorder or Asperger's disorder or some other condition was present. However, in practice, PDD-NOS was a diagnosis that frequently stuck and followed the child for quite a long time. The other two other conditions in this category were Rett's Disorder and childhood disintegrative disorder. These were both neurodegenerative conditions that are genetic or neurological in origin and are much rarer than the other three conditions, as it turns out.

The DSM-4 specified that a diagnosis of autism or Asperger's syndrome or PDD-NOS needed to be rendered by the time the child was three years of age and the presenting symptoms should be there for the diagnosis to be rendered by that time. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association, after a long period of study and consultation with many autism experts, set forward a new group of diagnostic standards. They did away with the category of pervasive developmental disorders and renamed a category of autism spectrum disorders all for itself. In a sense this gave the diagnosis of autism a greater standing in the psychiatric community. They completely revamped how autism was diagnosed and while you will still see the communication, social, and behavioral components in the diagnosis, they became a little more specific in terms of exactly what behaviors we wanted to look for. This is a good change and one that has helped us to know what we're looking for better than we did before.

Specifically, for a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders there will be social, communication, and interaction deficits, restricted behaviors, activities and interests similar to before. Now, instead of diagnosing autistic disorder, Asperger's disorder, PDD-NOS, autism is diagnosed based on a level of severity. Level 1 individuals with autism are those that require the least support. They have more communication. They're much more verbal. They are going to communicate in sentences or conversationally. Level 2 individuals need some support from others. Level 3 are individuals with autism who have minimal verbal ability, certainly limited understanding of language, limited social skills, and behavioral aspects that would be expected and they are going to require very substantial support to be independent. No longer does the diagnosis have to be rendered by age three, but rather just very early in development.

Diagnoses Then and Now: A Comparison

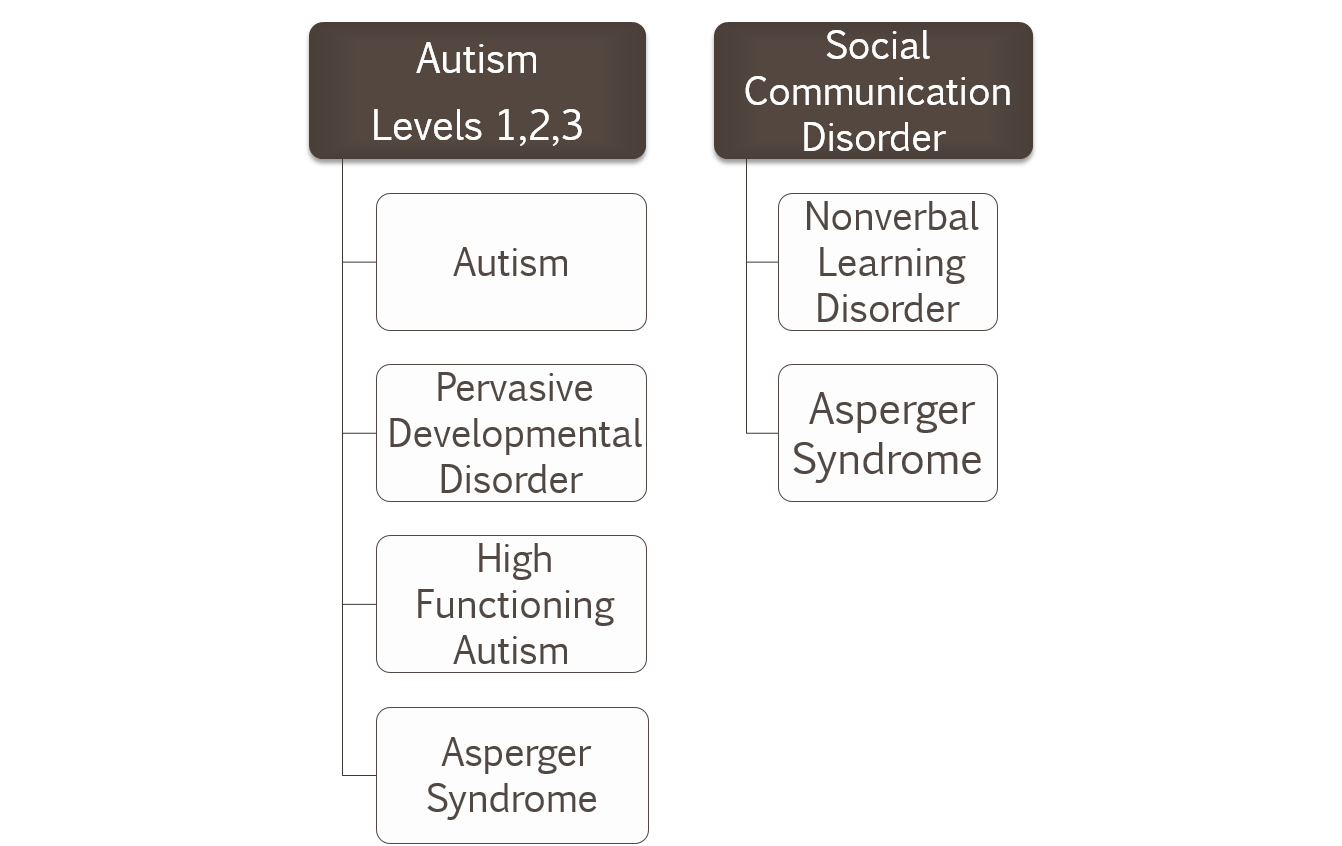

The diagnoses then and now could be laid out according to Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagnoses Then and Now: A comparison.

On the left side of figure 1, there are autism levels 1, 2 and 3. This used to be represented by diagnosis such as autism, pervasive developmental disorder, high functioning autism, or Asperger's syndrome, but the new diagnosis would either be at level 1, 2 or 3. We would expect people who formerly had a diagnosis of Asperger's syndrome or high functioning autism to be level 1 and people with autism or a diagnosis of PDD-NOS would most likely be at 2 or 3.

They also added a new diagnostic category – social communication disorder. This one is especially interesting for speech language pathologists. These are individuals who evidence all of the pragmatic language deficits that we often see such as difficulties with nonverbal communication and difficulty interacting with others. But, they don’t have all of the other symptoms of autism. Diagnoses that were commonly used in this category before were nonverbal learning disorder and some people with Asperger syndrome may have fallen into this category as well.

ASD: Social Communication and Interaction Deficits

Let’s take a closer look at the criteria to help you sort out the criteria that were used formerly and those that are being used in new diagnostic evaluations since 2013. There are new diagnostic standards for diagnosing autism spectrum disorder.

Social-emotional reciprocity. The APA specified that this is a disorder with primary social, communication, and interaction deficits. Notice that the language has changed and that they're understanding that the social communication piece of this is very important and that individuals with autism present persistent deficits in these areas, particularly in the area of social-emotional reciprocity. For example, failing to engage with other people, failing to be interested in the communication of other people, difficulty initiating, difficulty taking turns. Perhaps there is difficulty with joint attention, just sharing attention with another person you want to communicate with, difficulty showing off and sharing the joy of something with another human being. These are characteristics that we don't see in children with autism early on. Some of these skills can be developed and we work very hard to develop them. But when we see a child for a diagnostic, we're looking for these kind of core deficits in social-emotional reciprocity.

Nonverbal communication. We're also looking for deficits in nonverbal communication. I was glad to see the APA including this category because it's very important. Nonverbal communication are those nonverbal communicative messages that carry so much meaning, like our eye messages. What are we saying with our eyes? Are we saying that we're interested in someone's communication or not? Are we saying with our eyes that we understand what someone's saying or we don't? Are we saying with our eyes that we're being a little bit sarcastic and that our verbal message doesn't match our nonverbal message? There are all kinds of eye messages that we send to one another.

Similarly, we use our voice to communicate a lot of nonverbal information. Are we asking a question or are we making a statement? Are we hoping that someone's going to listen to us? Are we changing our vocal register when we talk to young children or when we talk to other people or not? There are many types of voice messages that we send to one another when we're sending a verbal message.

Then there's our body language that helps to get across our meaning. How close or far away we stand to people also says something about the communicative message that we're sending. People with autism don't read these signals very well. They're having a hard enough time decoding the verbal piece of the message and they're just not very good at being able to simultaneously read all of these nonverbal signals and encode meaning from them.

Negotiating social relationships. People with autism have difficulty approaching other people, knowing how to start a verbal or nonverbal interaction with them, and this goes on into having difficulty making friends and maintaining relationships later.

ASD: Restricted Behaviors, Activities, Interests

Another category in the new diagnostics standards is similar but kind of collapses across some of the former categories as restricted behaviors, activities, and interests.

Repetitive stereotypic movements, speech or use of objects. People with autism do have some repetitive stereotypic movements. Sometimes we refer to these as stereotypies, or motor movements that don't seem to have any purpose but are repeated over and over again. This also happens with speech in terms of echolalia, saying things over and over again for no apparent reason, and using objects repetitively, not necessarily for the function they were intended.

Insistence on sameness and routines. It was replete through Leo Kanner's early papers, that children with this new condition that he had identified wanted things to be the same. They wanted a routine. They didn't just want it. They seemed to need it. Anytime the routine was broken they would react negatively to it and often scream and tantrum. So this insistence on sameness and need for routine continues today as one of the seminal characteristics of this disorder.

Restricted interests; fixations. Individuals with autism are typically not interested in too many things and may be fixated on certain topics or on certain things. Often during a diagnostic evaluation, I often ask the family if given a short period of time to do whatever the individual wanted, what would they do. Usually, if the person has autism, the family can tell me one or two things that the individual likes to do over and over again, or with higher functioning individuals there is something they like to talk about over and over again.

Hyper- or hypo- sensory experiences. People with autism have a lot of altered sensory experiences. Quite simply, they don't experience the world the way you and I do. They're often hypersensitive to certain smells or sounds, which means that they don't hear things the way we do. They don't hear your voice the way I would hear your voice. They don't see things the way that we would see things. One time, a little girl with autism told me that my hair looked like a halo. When she described it to me more in depth, she said that she could see each individual hair on my head as if it was an individual thing rather than hair as you and I would see it. People with autism are not experiencing the world from a sensory perspective in the same way as you or I, so it may not be surprising that they're not responding to it the same way either.