From the Desk of Ann Kummer

We all know that children need to develop oral language skills before they are able to learn to read. Oral language development occurs when the child is exposed to casual talk (CT) in the environment. In addition, we know that the development of phonological awareness is a critical component in early reading in that it serves as a foundation for decoding the written word. What may be less clear to all of us is that, in addition to casual talk, the child needs to be exposed to higher-level academic talk (AT) for reading development. These higher-level skills are great predictors of later reading comprehension and academic success. Fortunately, Dr. Anne van Kleeck, PhD, CCC-SLP, who is an expert in this area, will answer our questions about this important topic in the 20Q article.

Dr. van Kleeck is Professor Emerita at the Callier Center for Communication Disorders in the School of Behavioral and Brain Science at the University of Texas at Dallas. Over the past 45 years, she has taught courses and conducted research on preschoolers’ language development and impairments, focusing particularly on the kinds of preschool oral language skills that provide critically important foundations for preschoolers’ later literacy achievement and academic success. Dr. van Kleeck’s publications include 5 edited books (one also translated into Swedish), 25 book chapters, and nearly 50 journal articles. She has given over 250 invited and peer-reviewed presentations nationally and internationally. Over the course of her career, she has also been the major professor for a total of 45 master’s theses and doctoral dissertations. Dr. van Kleeck has twice received the Editor’s Award for the best article of the year in the American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology (1994, 2014). In 2011, she received the International Reading Association’s Dina Feitelson Research Award. Dr. van Kleeck has been a Fellow of ASHA since 2013 and in November 2018, she received the highest award given in her discipline for her career-long research accomplishments in language science, the Honors of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA).

In this article, Dr. van Kleeck explains the importance of focusing on these higher-level oral language skills when preparing preschoolers, particularly those with language impairment, for later reading development. She also discusses the purpose of academic language, its components, its development progression, typical cultural variations in preschoolers’ exposure to it, and ideas for teaching it. This article provides a lot of interesting and practical information.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Focusing on Academic Language in Preparing Preschoolers

with Foundations for Later Reading Development

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Explain why various aspects of academic language (or academic talk) are important language goals with preschoolers

- List different aspects of academic language

- Define ways in which academic talk (AT) is distinguished from everyday casual talk (CT)

- Demonstrate ways to foster AT in preschoolers during a storybook read aloud

Anne van Kleeck

Anne van Kleeck1. To prepare preschoolers and kindergartners with language impairments that I work with for later reading, I focus on phonological awareness skills with them. Am I doing enough to help them make as smooth of a transition as possible to learning how to read?

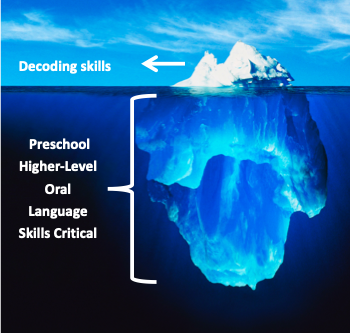

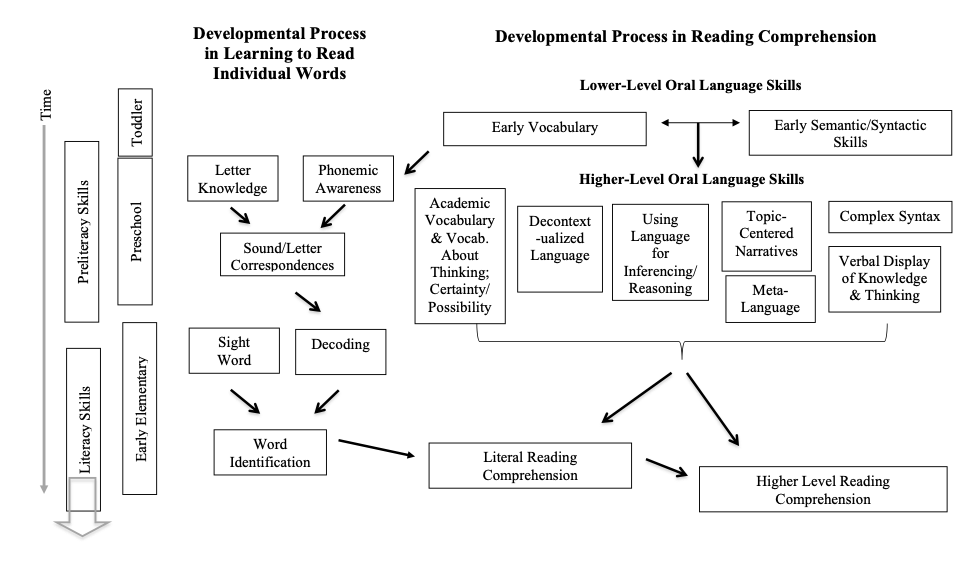

Phonological awareness (PA) skills, particularly at the phoneme level (knowing that words are made up of individual sounds), are very important foundations preschoolers can learn that will help them as they later learn to decode print (figuring out which spoken word each printed word corresponds to). This certainly helps tremendously in learning to read individual words in our alphabetic script, which is essential to being able to comprehend text. However, learning the foundations for decoding is the mere tip of the iceberg in laying preschool foundations for learning to read. We need to also be thinking about higher-level oral language skills that are foundations for later reading comprehension. These skills, as shown below are “less visible” (letters are much more concrete). They are also more complex and more difficult to teach and measure.

2. What are the higher-level oral language skills important for reading comprehension and academic success?

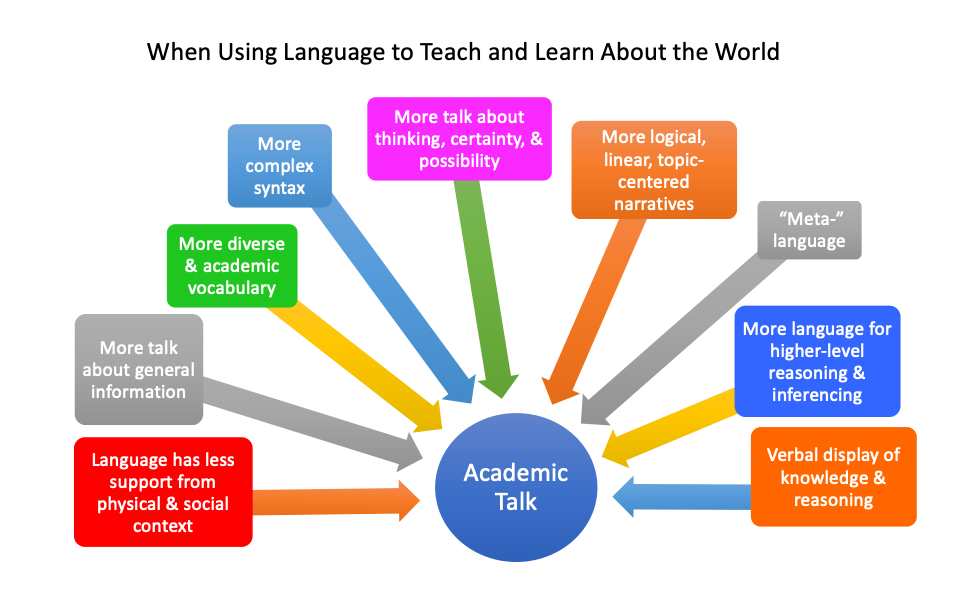

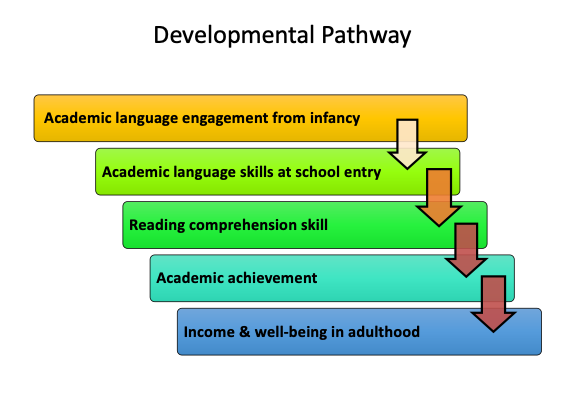

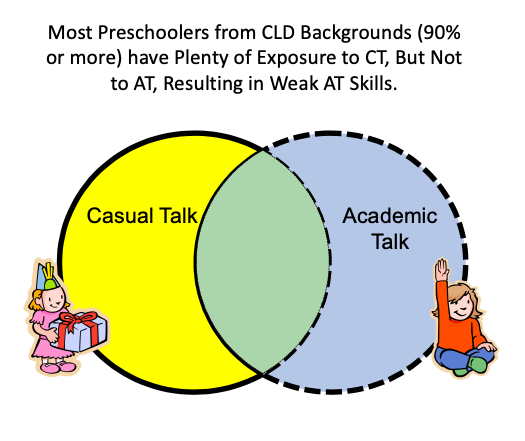

The higher-level oral language skills are shown in the figure below (see van Kleeck, 2014a, 2014b, 2015). When language is used for school (or school-like) teaching and learning about the world, these higher-level language skills need to be more frequently used than when language is used for everyday living reasons (called casual talk, or CT). For this reason, I refer to these higher-level language skills as academic language or, because they begin to be learned only orally at the preschool level, academic talk or AT. CT and AT are two different registers of English.

3. What do you mean by “verbal display of knowledge and reasoning” that you list as one of the AT skills in the previous question?

Preschoolers whose parents have higher levels of education are often called upon to display skills they are in the process of learning. Verbally, they are often requested to answer many questions in order to show and adult what they know, and not to provide information that is unknown to the adult asking the question. Another type of verbal display (see van Kleeck & Schwarz, 2011) requests that children display their thinking or reasoning rather than show what they already know. Both of these types of verbal display are very commonly requested in school. Preschoolers from CLD backgrounds may not get as much experience in responding to requests for verbal display in their homes. They, therefore, might arrive at school less familiar with this aspect of the AT register, and therefore less comfortable engaging in verbal display.

4. What can I do, or suggest that a teacher do, for preschoolers who are not familiar and comfortable with engaging in verbal display?

Preschoolers need to understand what their role is when such questions are asked. This may be particularly necessary because at least a small amount of evidence indicates that children from some culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) backgrounds may be discouraged from answering such questions, or they may be used to tease or chastise in their cultural groups (see van Kleeck, 2014b, for discussion). I have elsewhere offered the following ideas for explaining verbal display to preschoolers who are not used to performing in this way (van Kleeck & Schwarz, 2011). For verbal display of knowledge, you might say something like the following, “Because we are in school, I’m going to ask you and the other children questions I already know the answer to. That helps me know if I’m doing a good job teaching you. If you don’t know the answer, that’s okay. Maybe another child or I will give the answer.” For verbal display of thinking, you might explain by saying, “Sometimes, you might not know the answer to questions I ask, but you can think about what the answer might be, and you can tell us what you are thinking.”

5. How do AT skills foster academic success?

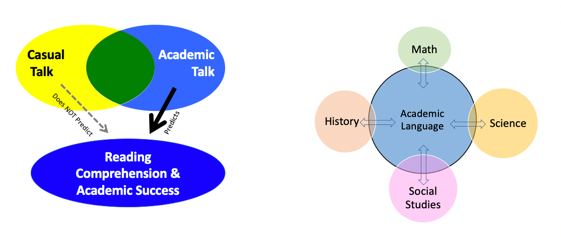

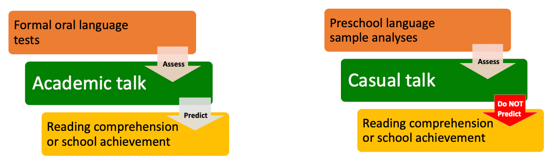

First of all, preschool and kindergarten AT skills predict later reading comprehension and academic success while CT skills do not, as shown in the first figure below (although for children strong or weak in both AT and CT, either will predict later reading comprehension and academic success, but only because skill in both will be highly correlated). Second, AT skills allow access to the curriculum, whether presented in oral or written format, because they are the “currency” of the classroom. Teachers focus on academic content areas, but typically do so without realizing that academic language is central to teaching all of them, whether in oral or written form. This puts children not as adept at academic language at a distinct disadvantage for accessing the curriculum. The second figure below shows the centrality of AT to academic content areas and attempts to also depict, by using bidirectional arrows, how growth in the academic content areas also creates growth in AT.

6. Given that the reading curriculum in first and second grade is usually focused on children learning to decode print, isn’t it developmentally inappropriate to be thinking about reading comprehension with preschoolers and kindergartners?

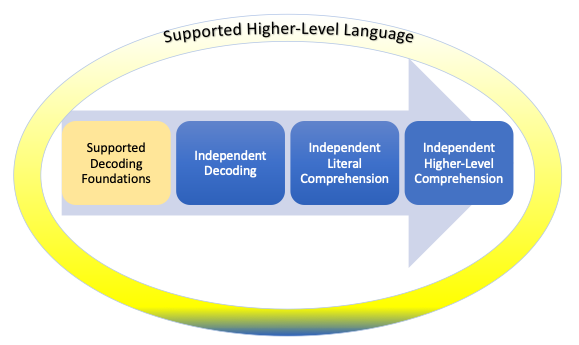

Early foundations for both later decoding and reading comprehension ideally begin long before children learn to independently decode print or engage in reading for comprehension. This can occur as their parents and others frequently engage them in school-like learning, which happens more often when parents have higher education levels. Such parental discussions involve engaging children in conversations that describe and explain the world, and simultaneously encouraging and supporting the children in using their critical thinking and language skills for these same purposes – the essence of AT. As I have attempted to depict in the first figure below, in these families, engaging children in AT “surrounds” – often begins before, and continues both during and long after – the period during which decoding foundations, later decoding skills, and independent reading comprehension are emphasized in the school curriculum. And, as is shown in the second figure, AT exposure can begin in infancy and leads to a variety of positive child outcomes over developmental time. And, of course, AT exposure from adults will become more and more complex over time as children continue to develop higher and higher levels of their own AT skills.

7. I’ve heard of lots of initiatives to encourage parents to increase the number of words they use with their toddlers and preschoolers in the home as a way to prepare them for the language demands of school. As an SLP, should I endorse this approach when asked about it by parents?

I would explain to parents that it is more important to think about HOW they talk to their children than to focus on how much they talk to them. How they talk should include frequent doses of AT. This seems to come naturally for parents with higher education levels, but for many parents, it might not come naturally at all. They will need to learn about the importance of helping their preschooler develop AT, and how they can do this both during everyday routine activities with their child and also during book sharing. As an example, while eating a meal or snack, parents can talk about the five senses – e.g., popcorn is crunchy, white, bumpy, tastes salty (and maybe buttery), makes a popping sound as you make it. They can also talk about where it comes from – a corn plant. Or they could ask a reasoning question – What do you think might happen if a whole barn full of popcorn caught on fire? As another example, during bath time, parents could talk about whether or not different bath toys sink or float; expand on a toy duck the child has by talking about ducks in general, where they live, how they can both fly and move on the water, etc.

8. If a preschooler I am working with is still having difficulty with using language to communicate with others in social interactions, shouldn’t I focus on these social interactive language skills before I consider focusing on the higher-level language skills needed for academic success?

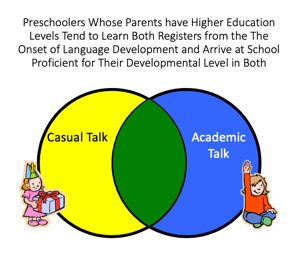

For children whose parents have higher education levels, everyday casual talk (CT) and academic talk (AT) are not developed sequentially, but are typically learned simultaneously from the very onset of the child’s language development in everyday routine activities as well as more “academic” activities, such as book sharing. So, as soon as a child can utter words, you can foster both, although both CT and AT will be at a very rudimentary level at first. Also be aware that if you wait until children are school-aged to focus on AT, they may be substantially behind in using this type of language at the start of school, which makes it more likely they will remain behind academically, as has been shown to be the case for many CLD children (see van Kleeck, 2014, for discussion).

9. If children in my caseload are in preschool, aren’t their teachers fostering academic language skills with them all day long, making it much less important that I add this focus to my language goals in working with them?

Although this will hopefully be changing in the future, academic language has long been part of what is referred to as the hidden curriculum. These are skills that are important to academic success, but are not directly taught to children in school (see van Kleeck, 2014, for discussion). They are not taught because teachers are rarely aware of the distinction between CT and AT.

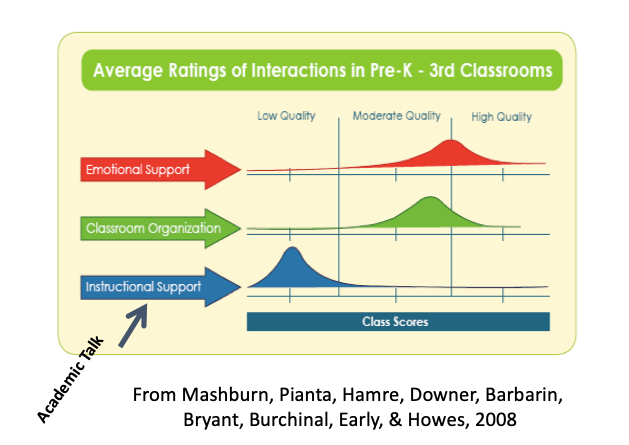

10. Don’t preschool teachers, like most more highly educated parents you have mentioned who are also very likely unaware of the AT register, just naturally use AT children in their classroom, even if they are not aware of it as a separate language register?

A large body of research shows that teachers of pre-K through grade 3 do well with providing emotional support for the children in their classroom and with organizing the classroom, but they do not do well in providing instructional interactions (which are basically synonymous with academic talk), (e.g., Mashburn et al., 2008). The results of the study, depicted below, are from a very large study of 2,439 children from 671 well-established pre-K classrooms in 11 states. The findings of this study are even more true of teachers serving low-income children (e.g., Pianta et al., 2005).

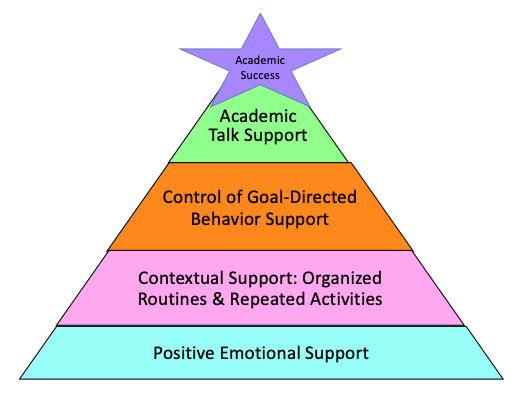

11. Emotional support and having organized classroom routines are also very important to children’s classroom learning, aren’t they?

They are essential. In fact, I think of them as foundational to learning. The problem is that they are just not enough. To maximize preschoolers’ chances for later academic success, we need to build two things on top of these foundations. First, preschoolers need support in beginning to learn to control their own goal-directed behavior so that they can attend well -- skills often referred to as executive functions (a detailed explanation of them is beyond the scope of this discussion). To be most effective, engaging children in academic talk rests on all of these important foundations, as I have depicted below.

12. Is it part of my job to help teachers understand what AT is?

As a language specialist, it would be very much in the purview of the SLP’s scope of practice to help preschool teachers learn about AT and its critical importance to preschoolers’ later reading comprehension and academic success.

13. How can I confirm the importance of what a teacher already knows about preliteracy skills related to decoding, while also expanding her or his knowledge to include AT foundations for later reading comprehension?

I think the best way to do this is by demonstrating that BOTH of these areas are critical, as I have done in the figure below that shows the foundations for decoding and for later reading comprehension. It might be important to point out that decoding skills are certainly important for reading comprehension, but they won’t take the child beyond literal comprehension of what she or he reads. Higher-level reading comprehension is essential for school success from the early school grades onward.

14. I have heard that many preschoolers from CLD backgrounds have weak language skills that put them academically at risk. Is this accurate?

Many researchers and educators continue to talk about how children from CLD backgrounds (who as a group are at risk academically) have “weak language skills.” But this is not accurate, because it is too broad of a claim. Approximately 90% of these children have perfectly adequate CT skills for use at home and socially – they do NOT have a language impairment. They learn to use language in the ways that they are exposed to it. Indeed, research has shown (Tomblin, Records, Buckwalter, Zhang, Smith, & O’Brien, 1997) that only 7.4% of kindergarten children overall have a language impairment, with this rate being somewhat higher for children in the following racial/ethnic groups, likely due to lower parental education levels: @ 11% of African-American; @ 12% of Native American; and @ 8% of Hispanic. But many children from CLD backgrounds do have very weak AT skills, and that is what puts them at risk academically (see van Kleeck, 2014a, and 2015). So, we shouldn’t just think of preschoolers’ language skills globally, but be aware of the differences between CT and AT.

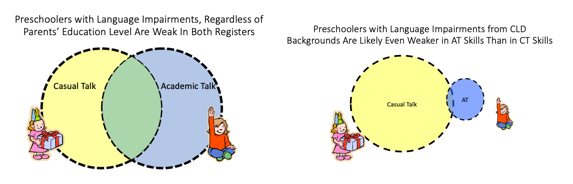

15. Are all preschoolers with language impairments weak in academic language foundations?

Because preschoolers with language impairments are weak in learning language regardless of the register, they will be weak in both CT and AT skills, as depicted in the first figure below. In preschoolers from CLD backgrounds who have language impairments, we might expect even greater weakness in AT skills compared to their CT skills, as the second figure shows.

16. How can I determine if a preschooler is weak in academic language skills?

As I discuss in van Kleeck (2014a), formal, norm-referenced language tests capture a preschooler’s skill with the AT register in a global fashion, whereas spontaneous conversational language samples analyses (LSAs) reflect skill with the CT register. For many preschoolers from CLD backgrounds, CT skills are often quite a bit stronger than AT skills, as noted in questions 14 and 15 above. In these cases, formal, norm-referenced language tests predict later these children’s later reading comprehension and/or academic achievement (e.g., Durham, Farkas, Scheffner Hammer, Tomblin, & Catts, 2007), whereas spontaneous conversational language samples analyses do not (e.g., DeThorne, Pretrill, Schatschneider, & Cutting, 2010).

Other children tend to perform equally on both of these types of assessments because they are equally weak in both registers (many preschoolers with LI) or they are equally strong in both registers (many preschoolers whose parents have higher levels of education). Since their performance on both AT and CT measures will be very similar (and not because CT predicts later school achievement) measures of either will interchangeably predict later reading comprehension and/or academic achievement. But for most children from CLD backgrounds, the figure below shows how different assessments capture different skills.

17. What is academic vocabulary, which is one of the areas of AT you have mentioned?

Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) considered three tiers of vocabulary. Tier 1 contains words of every day speech (CT) that are simpler and are used more frequently. Academic vocabulary has two levels, and these are lower frequency words. Tier 2 consists of general academic words that are used across the curriculum. Examples here would include words such as annual, demonstrate, directions, ignore, investigate opposite, represent, sequence, accurate, and pattern. Tier 3 academic vocabulary consists of words that are specific to a particular academic area of study. Preschoolers might be exposed to Tier 3 vocabulary such as eclipse, lava, evaporation, migration, hibernation, and metamorphosis. Discipline-specific words reflect more precise concepts.

18. How does the idea of “more precise” vocabulary jive with the idea of “more general information” used in AT? That is kind of confusing.

AT is general because scientific information is often about categories of things (hence more abstract) rather than about specific instances of things that are often familiar and personally relevant (often the when using CT). Categories can get more specific or more general (superordinate or subordinate categories), but they are still general categories containing all members of that category. You might talk about dormant versus active volcanoes, for example. Precise scientific concepts are often used to talk about categories of things, such as how all members of a category function or behave (e.g., they migrate; perform photosynthesis; are carnivores) and maybe how that is different from members of another category (e.g., they hibernate; cannot perform photosynthesis; are herbivores).

19. Could you tell me more about the idea of using language for inferencing or reasoning? I think I get the idea, but it’s a little fuzzy for me.

We use inferential reasoning in order to do things such as explain, problem solve, categorize, talk about cause and effect, predict, summarize, compare, contrast, describe, define, justify, and give examples. We have to engage in inferencing whenever information has not been directly provided for us. So, for example, we might show a preschooler a book she or he hasn’t seen before, read the title of the book, and then ask, “What do you think this book might be about?” To attempt to answer this, the child needs to infer what the book might be about from the picture on the cover and from the title we just read to them. The child has not been directly told what the book might be about; she or he has to infer that information. Children often need to infer in everyday contexts, but they are very frequently called upon to verbalize their inferences in school.

20. AT introduces a lot of new aspects of language to focus on with preschoolers. Do you have ideas for integrating them into one activity?

A program I developed (and have documented the effectiveness of) is called TAB4I, which stands for Talking About Books Builds Big Brains Intervention. It uses scripted questions and discussions during read alouds to incorporate many dimensions of AT (often more than one simultaneously). Referring back to the subareas of AT shown in question 2, ideas for fostering some of the aspects of AT (using a published children’s storybook) are offered below after the storyline is presented.

Story Line of Moonbear’s Shadow by Frank Asch: A bear, who is simply called Bear in this story, goes fishing and his shadow scares the fish away. The entire story focuses on the Bear’s various attempts to make his shadow go away so he can resume fishing. At first, he just tells it to go away, but it doesn’t. Then he tries to run away from it, and that doesn’t work either. His subsequent failed attempts included hiding behind a tree, climbing high up on a cliff, nailing his shadow to the ground, burying his shadow in a hole, and slamming the door to lock his shadow inside. Finally, he makes a deal with his shadow that “if you let me catch a fish, I’ll let you catch one.” Because the sun is now high in the sky, he no longer has a shadow, Bear is able to catch a fish. His shadow catches one, too.

Language less supported by the physical context: Book content is removed from the immediate physical context, so this is a given during book sharing.

More talk about general information: In the story, a fish is scared away by the bear’s shadow. This is a specific fish. To extend this event to general information, the adult could comment about fish in general and say something like, “Fish don’t know that shadows aren’t real things – they just sense that something is near them – so they swim away so they are safe.”

More diverse and academic vocabulary: In the book it says, “Now Bear was very annoyed.” The adult could elaborate first ask the child what “annoyed” means. If the child cannot supply an adequate definition, the adult could say, “Annoyed is a fancy word for being a little unhappy or bothered about something. It’s not being very angry, but just a little bothered.”

More complex syntax: The adult could prompt a longer, more complex sentence by asking, “Moonbear has tried so many things to get his shadow to go away. Can you tell me all the things he has tried?” To support the child in doing this, the adult might supply temporal adverbials in carrier phrases such as, “And then next he tried to . . .”

More talking about thinking, certainty, & possibility: The adult could model this kind of language by saying something like the following, where these kinds of words are in bold, “I think maybe this book is going to be about the bear on the cover and his shadow, because the title is Moonbear’s Shadow. But I’m just guessing, so we’ll have to read the book to find out for sure.”

More logical, linear, topic-centered narratives: Ask the child to retell the story to a stuffed animal that did not hear it because it was asleep, and support the retell as needed.

More meta-language: The adult could say, “This book is called Moonbear’s Shadow.” And then ask, “Do you see a letter in this title (underline the title with finger) like the first letter in Miguel’s name here?” If the child cannot respond adequately, the adult could point to the M in Moonbear, and say, “M, that makes the mmmmm sound. Miguel’s name both start with the same sound, Mmmmmmm – Mmmmoonbear and Mmmmmmiguel.”

More language for higher-level reasoning and inferencing: Ask the child to predict what the Bear could possibly try next to make his shadow go away. This is also an example of verbal display of reasoning. There is another example below.

Verbal display of knowledge and reasoning: The adult could ask where Moonbear’s shadow is in one of the book illustrations (knowledge); After Bear tries to nail the shadow to the ground, the adult could ask, “Do you think that will work?” Why (or why not)?” (reasoning).

References

Asch, F. (1985). Moonbear’s Shadow. New York: Aladdin.

Beck, I., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life, second edition: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Biber, D. (1995). Dimensions of register variation: A cross-linguistic comparison. New York: Cambridge University Press.

DeThorne, L. S., Petrill, S. A., Schatschneider, C., & Cutting, L. (2010). Conversational language use as a predictor of early reading development: Language history as a moderating variable. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 209 - 223.

Durham, R. E., Farkas, G., Scheffner Hammer, C., Tomblin, J. B., & Catts, H. W. (2007). Kindergarten oral language skill: A key variable in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 25, 294 - 305.

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D. Burchinal, M., Early, D. & Howes, C. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development 3, 732-749.

Pianta, R. C., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Bryant, D., Clifford, R., Early, D. M., & Barbarin, O. A. (2005). Features of pre-kindergarten programs, classrooms, and teachers: Do they predict observed classroom quality and child–teacher interactions? Applied Developmental Science, 9(3), 144-159.

Tomblin, J. B., Records, N. L., Buckwalter, P., Zhang, X., Smith, E., & O’Brien, M. (1997), Prevalence of Specific Language Impairment in Kindergarten Children. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 40(6), 1245-1260.

van Kleeck, A. (2014a). Distinguishing between casual talk and academic talk beginning in the preschool years: An important consideration for speech-language pathologists. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23, 724-741. Recipient of 2014 Editor’s Award for Best Article of the Year in this journal.

van Kleeck, A. (2014b). Intervention activities and strategies for promoting academic language in preschoolers and kindergartners. Journal of Communication Disorders, Deaf Studies & Hearing Aids, 2; 13 pages (Free online at open access doi: van Kleeck, A. (2015). The academic talk register: A critical preschool oral language foundation for later reading comprehension. In A. DeBruin-Parecki A. van Kleeck, & S. B. Gear (Eds.), Developing early comprehension: Laying the foundation for reading success. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes (pp. 52 – 76).

van Kleeck, A. & Schwarz, A. L. (2011) Making “academic talk” explicit: Research directions for fostering classroom discourse skills in children from nonmainstream cultures. Revue Suisse des Sciences de l’Éducation, 33 (1), 1-18.

Citation

van Kleeck, A. (2020). 20Q: Focusing on Academic Language in Preparing Preschoolers with Foundations for Later Reading Development. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20349. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com.