Editor's Note: This text is a transcript of the course, External Cognitive Aids for Adults with Acquired Cognitive Deficits, presented by Jessica Brown, PhD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the impact of cognitive deficits on functional outcomes and examine rehabilitation models appropriate for this population.

- Describe a three-phase model associated with external aid selection, design, and implementation.

- List considerations for implementing external aids for cognitive deficits commonly associated with traumatic brain injury and dementia.

Cognitive Deficits & Impact on Functional Independence

Thank you everyone for joining me. Today we're going to talk about the use of external cognitive supports for individuals with acquired cognitive impairments across the spectrum. Then we will focus on a few populations where some of the supports we discuss may differ depending on who you're working with and what type of cognitive concern they have.

Let's first discuss what cognitive deficits might exist that could impact functional independence and why someone might consider external aids as the appropriate rehabilitative method. What do I mean by cognitive deficits? Depending on what you read, there are different definitions of what this term means.

I've listed nine different components of cognition below.

- Initiation

- Inhibition

- Processing Speed

- Planning

- Organizing/Sequencing

- Problem-solving

- Cognitive Flexibility

- Self-awareness

- Attention & Memory

The first eight components are adapted from McKay Sohlberg's definition of executive functioning. What I like about her definition is that it breaks apart different components of executive functioning into discrete tasks or skills so that we aren't saying, "I'm working on executive functioning" Rather, we can pinpoint what the particular issue is. When we talk about individuals who might need external cognitive aids, it could be for any one of these different areas of executive functioning. What typically comes to mind the most are skills like planning and organization. However, I also combined the very big ideas of attention and memory.

Rehabilitation Efforts

Traditionally, we may think about external cognitive supports being more appropriate for people in post-acute or later stages of rehabilitation, where we might work on executive functioning deficits. However, individuals in more acute stages who might be showing impairments in attention and memory, are also potential candidates for use of these aids. Later in the course, we will talk about the different considerations depending on the characteristics that somebody is displaying cognitively.

Personalized Education

When we think about how to support these cognitive impairments in individuals with acquired deficits, we have many different options as rehabilitation professionals. I have provided options in four main categories. The first one is personalized education where we are talking to the client about what their impairments are, what a brain injury is, what a stroke is, or what a brain tumor is. We are talking about how that diagnosis or deficit might impact their ability to function.

Direct Approaches

We also might engage in direct or restorative intervention approaches. There's not a lot of great evidence to support direct intervention for individuals with cognitive impairments, except maybe in the area of attention. Although direct intervention, such as drill and practice, is very appropriate for a variety of different areas of our professional scope of practice, it doesn't lend itself well to cognition.

Compensation & Metacognition

The last two areas, compensating for impairments and increasing metacognition are where the "bread and butter" of our rehab efforts lie for individuals with neurological deficits. This is what the literature supports in terms of the most effective practices as well. Compensation can mean many things. It could mean that you're teaching someone to use an internal memory strategy, for example. However, for our purposes today, we're going to talk specifically about how compensation for cognitive impairments can be achieved through the use of external aids. I want to point out that external aids don't always mean technology. I couch those as two different things. Assistive technology may be appropriate for some people and I will cover that later. What I am referring to is anything that's outside of the person that they can refer to, use, and engage with to promote success and work around some of their challenges.

Rationale for Compensation

What are some of the rationales for choosing compensation as your rehabilitative method for cognitive impairments? We have seen a lot of attention given in clinical practice and in research about external aid being used in a variety of ways. This could be writing down a to-do-list, using a daily planner, or even using a photograph to support memory.

The current literature shows that the use of these supports can help foster increased independence, which is always the goal of our rehabilitation efforts, especially with adults. In 2011, Cicerone and his colleagues describe what cognitive rehabilitation should look like, and in their literature review, they discuss direct attention training. We can do some of that deficit type of rehabilitation for attention, memory, and metacognitive strategy training. But, those efforts should be coupled with the use of internal and external compensatory supports. That is the important piece. Again, the research supports the idea that the most efficacious and important clinical approaches should be combined with the use of support materials and external cues.

These support materials are, hopefully, the external cognitive aids that we are designing, selecting, and helping our clients implement. When we think about the use of external cues, traditionally we think of the cues that we, as therapists, or caregivers might provide. However, it's possible that the support materials themselves could serve as the external cues. I will share the features of some materials that might best support cognitive use and independence, as well as some that embed external into the systems.

We should also consider looking at the expert recommendations about rehabilitation and cognitive therapy. In 2014, there was a series of papers published called the INCOG recommendations. I highly suggest, at the very least, looking at the abstracts because they are a series of very extensive reviews of the literature that focus on a variety of topics. One of the articles that I referenced in this course is about cognitive-communication impairments (Togher et al., 2014). There are also specific pieces of literature on attention, processing speed, and memory. The cognitive-communication paper by Togher et al. discusses four general ideas that are going to enhance therapy:

- Consider premorbid status - considering who the person was before their injury or before their diagnosis

- Individualize goals, skills, therapy approaches

- Include training in assistive technology use, when appropriate

- Occurring in a context that doesn't require generalization

If we make our therapy approaches functional in the beginning, then we don't have to worry about whether those techniques or skills will generalize to real life. When I look at those four points, it is a lot of great information but it's pretty challenging to achieve all of that. Therefore, in practice, I want to find ways to concretely achieve those different aims.

Functional Impact

We need to consider the functional impact of these materials and aids. What are the systems or materials going to do to support the individual in their daily living? There may be multiple strategies or supports that we want to teach, so we might have to focus our intervention efforts on determining which materials might be helpful in a variety of situations. What a person needs in their home may be vastly different than what they need when they're attending a medical appointment.

How we can personalize these materials? It's not a one size fits all approach and we want to figure out how to use these support systems in a variety of different ways. I like to think of external cognitive aids as brain prostheses. Just like somebody with a limb impairment would rely on a prosthetic device, these external aids can serve as a prosthesis for the brain. The aid is there to be a support that an individual can rely on to participate fully in their everyday world.

External Cognitive Aids: Current Practices

I started pursuing this line of research because of an experience I had as a master's student in an inpatient rehab facility. I was lucky to spend three months full time in an inpatient rehabilitation unit that was primarily associated with stroke, traumatic brain injury, and some spinal cord injury. In that inpatient rehabilitation unit, every person who we had any cognitive concerns about was given a one-subject spiral notebook. The notebooks had a page about biographical information, the monthly calendar, a list of therapies, some contact information for people, and a type of routine log. We did this for every patient we were seeing, including what their impairments were, and why. It was the support that was put in place in that setting, and I started to think about how much adaptation that particular material required from me as a therapist when I was working with different people. I remember trying to rely on all of the techniques that I thought worked for me. I was circling different things in the notebook, highlighting things, drawing arrows to other things. I was doing anything I could do to support the person, and I realized I had absolutely no evidence to support those decisions. I was doing it because I thought it might help.

So I really started to dig into the literature and found that external aids work, but we don't know how they work, what parts of them work, why they work, or when they work. We are using the resources that we have available that might be the most efficient, the easiest, part of the routine in our setting, or based on our own experiences. But, we don't have a lot of literature on how to do these external cognitive aids. So that's a lot of the motivation I had as a clinician and as a researcher to try to answer some of these questions.

Theories of Technology Acceptance

There are some theories regarding technology acceptance that we can consider. Technology acceptance is not necessarily the same thing we might think of in rehabilitation with augmentative and alternative communication technology. If we think broader, we want to figure out why people decide to adopt a specific kind of aid or technology, and potentially why they abandon other systems. We do know that regardless of the theory, most of the ideas have to do with some sort of social validity. Meaning, does this system actually match what the person needs in their life? Is it something they can easily use based on the things they need to do?

When selecting a support for somebody, we need to determine what components will match the person's strengths and challenges. Additionally, we need to make this more of a phased approach rather than a simple selection and implementation process.

How do we do that? There are a lot of resources available to help us figure that out. One is called the Matching Persons with Technology process. This is not something that I created, but I do rely on it a lot for adapting strategies to different populations that I work with. It's a very systematic, yet personalized, approach to gain information about the individual and to match them to features of technology that would be most appropriate.

I love this quote from their website, "When matching person and technology, you become an investigator, a detective. You find out what the different alternatives are within the constraints." So, it's a very iterative process. If you go to the Institute for Matching Person and Technology website (https://sites.google.com/view/matchingpersontechnology/home), there are many different sublinks. The website provides information about the research that has been done to create this method. It provides some of the rationale behind using this approach and there are even some videos to walk you through the process. One of the most beneficial things about this website is the forms and workbooks that are publicly available.

The idea of matching persons with technology was started by Marcia Scherer who is an editor for the journal, Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, which is very helpful because it focuses on this type of work. If you want to know more about this area, a good place to start is with this website and journal.

Procedures for Evaluation and Implementation

Because this matching persons with technology process exists, I began to realize that I could take some of the spirit of that process and focus it on individuals with acquired neurological deficits. A few years ago, I started to look at a process for evaluating and implementing an external cognitive aid. Some of the work that I'm going to discuss is specifically with individuals with traumatic brain injury, but this entire process can be matched to a variety of individuals. I've been doing a lot of work with people with brain tumors recently, and this three-phased approach works well for this population also.

Phase 1: Evaluation (Needs Assessment)

To start, we determine what the needs of the user might be. What will our evaluation look like? What are some of the methods that we could use to evaluate people? What are we trying to support? To answer these questions, there are a variety of things that I recommend.

First, complete an in-depth case history. Obviously, some of the individuals we support may be better historians than others. An in-depth case history may be easy to procure or it may be quite difficult. We all know that when we review medical records there is a wide range of specificity and detail that is provided in those records and we may need to rely on the individual or some other informant to help us gain this kind of information.

We also want to definitively and objectively determine the client's strengths and weaknesses. This could be obtained with a self-report or symptom checklist. But relying on the individual with the impairment may not necessarily give us everything we need. We may need to think about alternative methods for getting more descriptive information.

Then we want to determine what the client's goals are in order to promote their independence and improve their functioning.

Needs Assessment: Provider. Let's talk about a needs assessment from your view as the provider. This could include anything in your typical assessment battery. Depending on your setting, you may have protocols from your specific institution or your assessment may be dependent on whether you're working with someone in acute versus chronic stages.

I don't have specific suggestions on how to evaluate your client. But I will say that the use of publicly available standardized measures to show the potential benefit of external cognitive aid use is easier said than done. We know that there are a variety of standardized assessments available for evaluating cognition. Those can be very beneficial to gain quantitative data, but they may not inform us about functional performance. To gain information about a client's functional performance, we want to consider their strengths and challenges in dynamic ways. We may want to do some type of trial and error with different aids and systems or we may want to look at the aids and/or systems outside of the context of a therapy room.

Also, from the matching persons with technology assessment process, we can do a technology device predisposition assessment. This allows us to consider the user's abilities across a variety of areas. How you gain that information might look really different. For example, maybe you know the person so you can answer a lot of these questions. Maybe it's bred out of your standardized assessment or maybe you include the individual in trying to get some of this information. The idea is that you don't have to think about what all the potential impacts of technology might be. The assessment provides you with various prompts to get the information. It asks about the person's social skills. It asks if they can appropriately use systems in a variety of different ways. It asks if social skills are going to be a barrier or do we need to support them socially through the use of some kind of system? Do they desire to work or go to school? What is the person's desire to use technology? Depending on the person, they may or may not be interested in technological processes, but the overall idea is to look at how many of the assessment items are either disincentives to technology use or major incentives to technology use.

Here is a link to the form: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xikD7cUvC8ekLLMQ_cZOuSlPfqDYdjQf/view. Again, this is a form that you, as the provider, would complete. There are many questions that address a variety of different areas. As I mentioned, there are questions about the desire to return to pre-injury roles and responsibilities, such as school and work. It addresses how the person feels about themselves; what are their coping skills? These questions can provide some insight into how motivated the individual might be to use an external aid. As you can imagine, if somebody has poor self-awareness, poor self-esteem, or isn't motivated to be independent, they're not likely to use one of these systems or aids anyway. So we want to take that into consideration and this assessment can guide you through that.

The assessment first addresses some of those global areas and then addresses the person's current level of skill in order to match a particular area or a particular type of aid to those skills. For example, a lot of people we work with might have physical or sensory demands that limit their ability to engage with technology or engage with a particular aid. If we are working with an individual who has visual problems, we might have to consider size, color, background, etc. If we are working with a person who struggles with literacy we don't want to use something that relies on written words or text very much. Again, this is a great way to get going in the process and figure out what the individual might bring to the table to facilitate success with using aids or not.

Needs Assessment: Consumer. We also want to gain information from the consumer. I mentioned that self-awareness might be a significant barrier and that's an important theme for us to consider. Obviously, many individuals with acquired neurological disorders are going to show challenges in self-awareness. It's a hallmark symptom of traumatic brain injury and certain individuals with right hemisphere dysfunction. Individuals with dementia do not have a very clear sense of self, awareness of their environment, or their needs. So that is something we want to incorporate into our therapeutic models as well as acknowledge up front that it's something important to consider when selecting the appropriate support for these individuals.

Additionally, we want to make sure that the needs of the individual actually match their preferences. I don't know about you, but I don't really love doing what other people tell me I have to do. If we are the ones always making the decisions for our clients, the likelihood of them using it in their daily lives is not very high. They might not have the best awareness of their deficits and their challenges, but their preferences are going to be key to figuring out how to match them with appropriate supports.

The consumer can also complete a survey of technology use (Link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1b8UmOpY-RN8VTo6OJLOSo3lX0Y9Yzlqi/view). There may be some barriers depending on the level of cognitive status or if they are in acute versus chronic stages, etc. but the idea is to prompt the individual to provide information about how they feel about using different technologies. For example, what have they used in their past that they feel has been successful? What are their frustration levels with using technology? Some may think they are really good at learning a new system or are tech-savvy. Others may say they are not. There may be certain types of technology that they're good at and others that they are not. This survey of technology use is a systematic way to get that type of input from the individual.

As I mentioned, depending on the user and their abilities, they may be able to fill out this survey with more or less independence. If they are unable to complete it on their own, it can serve as a way to guide an interview. Also, an informant or somebody else can also help complete it based on what they know about the individual.

This survey is great because it prompts you to consider a variety of different kinds of technologies, everything from a VCR to a bank ATM. It's a very broad conception of what technology might be and it's categorical in nature. It uses statements that are very concrete for the consumer. It specifically addresses typical activities the person engages in, how social they are, and what some of their mental health concerns are. You get an overall score to help determine if somebody has a positive attitude towards using technology, whether they're neutral, or whether they're negative. Then you know if technology is something you want to pursue or how to adapt it. Again, it's a helpful starting point to gain some information that you may or may not get otherwise.

Needs Assessment: Informant. I mentioned earlier that an informant may be helpful with this process. I have seen a lot of clients in acute care or inpatient rehab who are not good historians and cannot be fully relied on for helpful information and making these decisions. That is when we may need to consider somebody else. Unfortunately, an informant may not be available to all people who need one. I can think of a lot of individuals who come into hospital settings with non-traditional backgrounds. They may not live at home, maybe their living situation is very unstable, maybe they don't have a support network, or they don't have somebody to rely on. We may need to do our best, but the idea is that an informant is best suited for helping you obtain an accurate history, and to make suggestions for future supports. I emphasize the word "suggestions" because ultimately this person is there to provide you with ideas, but is not the person I want to fully rely on. There are times in therapy, particularly when I'm working with adolescents and young adults, when I asked the informant to leave because they may be providing too much information. When I'm trying to find out what motivates the client that I'm working with, I sometimes ask the informant to provide information through a form or questionnaire, but they aren't dominating the decisions that are being made.

Motivational Interview. I like to use motivational interviewing as a generic method to gain information about my client and their preferences in order to make goals. I'm sure many of you have heard of this technique. Motivational interview techniques were not originally created for use by SLPs. It was actually something used very commonly in the medical field for determining how to support patients with different diagnoses. If you look up the literature on motivational interviewing there's a lot of information about working with people with diabetes, for example, and how we can figure out what their goals and needs are. A lot of it is related to medication management, but the idea is that a motivational interview is a framework that facilitates a collaborative process between you and your client. You are obtaining information from them about what they think their challenges are and what their goals are. Then you work together to form that into something realistic and manageable in your therapy. I like this as a clinician because sometimes I'm off the hook for trying to create the goals. A lot of the goals come from my clients and what they're interested in and what they think their needs are.

Let's talk about what a motivational interview looks like. The idea of it being really open-ended is what sparks the spirit of this technique. You start by asking a very open, generic question such as, "Why are you here today?" or "What can I do for you?" or "What can I help you with?" Maybe they tell you about a particular item and then you help them focus on that. You might respond with, "Okay, that's interesting. Tell me why that bothers you." or "Okay, you said that you're having trouble getting things done, how do you go about completing tasks in your daily life?" It's still open-ended, but you're narrowing the scope for them.

One of the important pieces of this is the validation of your client and what they're experiencing. You want to frequently reflect on what they're saying and help them understand that what they're going through is a real thing. For example, you might say, "It is really hard to stay focused for long periods of time. I have that problem too."Then at the end, you want to summarize and synthesize what you're hearing them say. An example is below.

- Practitioner: Why are you here today?

- Client: I’m having problems at work. I keep doing things wrong.

- Practitioner: Tell me about how you go about your day at work.

- Client: I’ve always been so good at knowing what to do, but now I am always confused and forgetting to do little things.

- Practitioner: It can be difficult to remember what needs to be done and make sure it happens.

- Client: Yes, my mind wanders and I forget what I’m supposed to be doing. Sometimes I look up and two hours have gone by.

- Practitioner: So what I hear you saying is that you’re struggling at work because you are confused and often lose focus or don’t remember what to do next.

- Client: Yes. It’s a huge problem for me.

What I want to point out is it can be an easy, smooth, and natural process to guide the individual and help them narrow their focus. I find that this works with people who have really impaired self-awareness. I also find that this works with people who we have concerns about their cognition or their ability to engage because, honestly, whatever they tell us is their current version of reality. Again this is an informative evaluation tool, not only for prioritizing and creating goals but also to informally evaluate where they are cognitively.

You can take specific training on motivational interviewing and become a certified expert in it. But, there is plenty of literature available for implementing it into your assessment process for a variety of different kinds of patients.

Phase 2: Selection

Once we know what the challenges are for the person and have utilized a variety of different techniques, we need to determine what type of aids will be beneficial for the individual.

In this phase, we want to make sure that we talk with our clients about the different options that might be available to them. We want to talk about things that they see as favorable to those potential options and things they see as barriers to those different options. Then, ideally, we would participate in a feature matching process (if that term is familiar to you from the AAC literature) to identify what we think will be the most preferred systems for the time being.

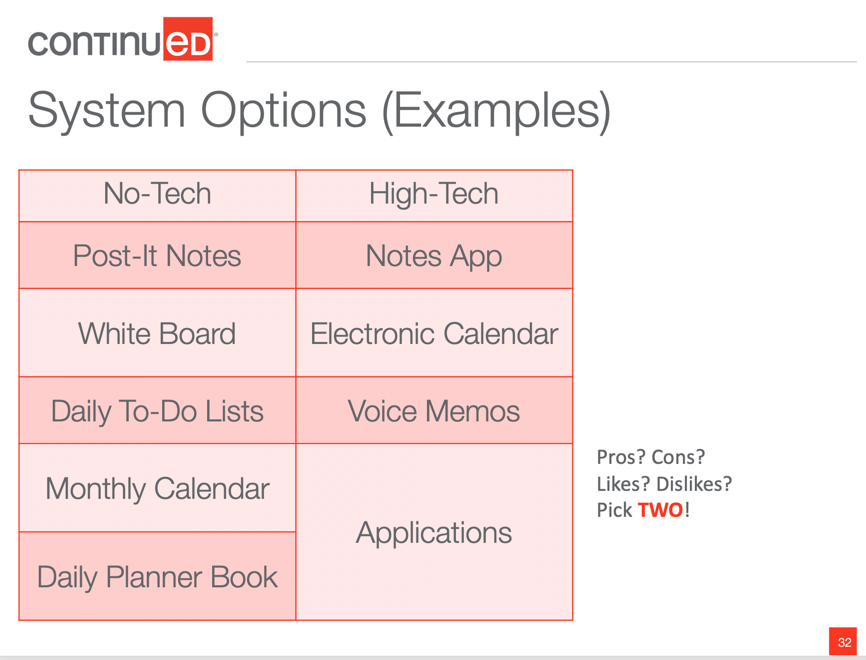

Here's an example of the options that I often go through with my clients and what I've used as a starting point in research.

Figure 1. System options.

I find it important to include both no-tech and high-tech options. You probably use a variety of methods in your daily life. How did you remember that this webinar was happening today? How do you remember that you had to pay a bill or call the doctor? Do you put it on post-it notes? Do you put it on your calendar? Do you write it down? What do you do that supports your ability to function in your daily world? It probably includes a few of these things. I literally have these options sitting out on a table and I talk to them about what all these different things are. I ask them to tell me about what they think the pros and cons would be of each item, what they like, what they dislike. Then, ultimately, I try to encourage my client or patient to select two of these that they will trial.

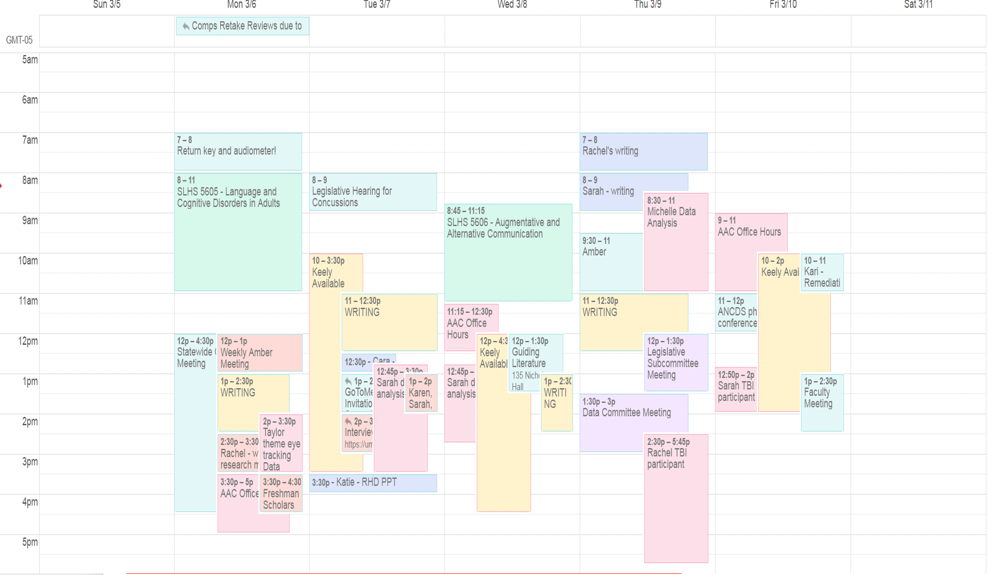

One thing we need to be careful about is that some of these systems or options might have way too many features. Figure 2 is a screenshot of my Google Calendar on any given day. I'm the kind of person who will color code things, you'll also notice that I am booked from start to finish in my day and I often have overlapping appointments.

Figure 2. Electronic calendar.

This type of system is highly inappropriate for most individuals with neurological disorders. Unless they were already familiar with this kind of system, we might want to shy them away from some options that might require a lot of new learning, or might have a big learning curve to get them started and going. Sometimes the best system is the easiest system. We don't necessarily want the system with the most bells and whistles. If a whiteboard works just as well, maybe that's where we need to start.

Preferred system components. Again, the goal is to pick two systems. When I do this with clients, I talk to them about the pros and cons, the likes and dislikes. Below is a summary of what I hear from people with neurological disorders about different options.

- Ability to be synchronized with multiple devices

- “The one thing that I think is really helpful is being able to sync my calendar with my phone”

- Visuospatial appeal

- “I’m a very visual person so if I don’t see something visually I’m not going to do it probably.”

- Accessibility and convenience

- “[Electronic devices] are really accessible…that’s a really big factor,”

- “The [online] calendar is much more efficient 'cause of the pop-ups 'cause like I always check my phone every 5-10ish minutes”

- Reminders

- “There was a reminder…at the time I needed it… so that was really helpful.”

- Structure with space for details, but not overcrowding

- “[I like] that there was a deadline and kind of a timeframe…I felt like it was easier to do when I had a calendar that showed me dates and stuff like that so I could plan it out better.”

There are trends about the components of systems that people prefer, not that everybody decides they like post-it or the Notes app, but that there are some generic features that seem to be preferred and work well for this population.

One thing that a lot of people tell me, especially if they have neurological issues, is that they wrote the information on their phone. But then they're sitting at their computer and that same information isn't there. Or they wrote it in their planner book, but then they forgot to bring that book with them so they don't have any of that information. The availability of accessing it and having it across multiple locations is very helpful.

With visuospatial appeal, some individuals are going to enjoy certain options like color-coding. For others, that's going to be a huge barrier. We want to match the visuospatial appeal to the particular user. That's something that you want to consider as a component of the system.

We need to think about accessibility. Many people will tell me that they wrote something down but then they don't remember to do it when the time comes. With electronic systems, what has been maximally effective for these individuals is the use of pop-ups. Setting up pop-up reminders on their electronic calendars can be really valuable and is a great way to combine the support system with the external cue. The external cue to use the support is actually embedded into the system. So those reminders can be key.

Many individuals are going to need help remembering the details of what it is they're supposed to be doing, but overcrowding is also not good. A dynamic system might work, such as using a monthly calendar to write down their appointments. For example, the doctor's appointment is written in the calendar, and then within that system in a different location all of the details are there about time, location, who it's with, et cetera. This can help them to not be so overwhelmed by what's going on within the systems.

When we talk to clients about their needs and the needs of people with neurological disorders, we want to consider the format of the system and the information that's in it. We want to personalize the system for them and include information that is relevant to that individual.

I try to remind myself that cognitive aids can be prospective and retrospective. Meaning, they are not only useful to help somebody plan and organize future events, they're also useful as a way to remember the past. I like to think of it as a living document that grows with the person and helps them move into the future. But, they can also rely on it if somebody asks them a question about their therapy appointment last Tuesday. It can serve a dual purpose of being a prospective and retrospective aid.

Phase 3 - Trial Periods & Implementation

What do we once we determine an individual likes the aids that we're recommending? Monumental to the success of these aids is trying them out. The most important phase is implementing the aids and the trial periods. If you have any experience with AAC, you know that you can't just hand somebody an AAC device and say, "Go communicate." We have to actually train the person. We can't just pick a system and send the person on their way. We want to make sure that what we've selected actually works for the user. So, we need something that allows us to make adjustments, to change our mind, to realize that maybe something didn't work and to go back and figure out a different method.

Training on the support system. How do we do that? If I'm going to train somebody on a particular support system, I need to train them on a variety of things. I need them to learn why the system is helpful - that's some of that education, awareness and metacognition. I also need them to learn how the system will help them. In what situations is it going to be useful? What's it going to do? Is it going to support your memory? Is it going to support your communication? They also need to learn when to use it. Without this background training, the likelihood of them pulling it out at the right time and engaging with it is going to be very low.

This is where we start our therapy. Do they know what these things are and what they might be used for? We will teach them this through guided practice. Maybe there are some role-play scenarios we can do. The idea is for the person to become really fluent in the use of these supports.

We also want to teach them the antecedents or the "triggers" for when to use it. It's possible that you find a support system that the person can use in any situation. However, there can be other systems that are only going to match a particular context or situation. In that case, we want to teach them what should trigger them to think, "Oh, I'm actually struggling with this particular task, I'm supposed to use my aid for that."

We also want to be sure that we can do this practice in a really real-life, functional way. When I think about what this means as a therapist and how I actually write goals and take data, it gets a little tricky. It's one thing to say we'll use an external aid to complete a task, but we also need to show that we are doing something that is goal-oriented, reimbursable in our therapy, and moving the person towards their long-term goal of independence with these systems. That can be hard to document.

One way to support this is to figure out the type of data you want to obtain when doing trial periods or teaching somebody about the support system. Some data might be the individual's ability to recall or know what the strategy is. For example, at an appropriate time, given a particular situation, do they know that a strategy might be helpful? That step could be a goal. The next step could be about their ability to use the system. Not only do they know when and what it is, but do they actually initiate use of it? Do they use it appropriately? Do they do these things with decreasing support? All of these different components can be embedded into ways that you write your goals and take session data to make it a reimbursable, skilled service. We must show the impact of our therapy.

TEACH-M strategy. The TEACH-M approach is a systematic way to teach a strategy. It could be a cognitive strategy, use of an external-aid, etc. It helps you start from a very distinct process to helping the person eventually implement it on their own.

- T - Task Analysis

- E - Errorless Learning/Spaced Retrieval

- A - Assessing Performance (Initial, Probe, Final)

- C - Cumulative Review (regularly review previously learned skills)

- H - High Rates of Correct Practice (multiple times per session and overtime) – shorter more frequent sessions are better

- M - Metacognitive Strategy Training (example: within-session prediction)

The "M" component focuses on the idea of self-awareness and metacognition. What does the person know about their strengths and weaknesses? Do they know that using an aid is helpful? Do they know when to use it? We want to incorporate that metacognitive approach and self-awareness training when we're helping our client use these external supports.

Another strategy is thinking of this as a progression of your client skill set. This comes from McKay Sohlberg's cognitive rehabilitation work that starts with helping a client acquire knowledge of the aid itself. For example, I might start by saying, "Here's your book. Can you tell me where you'd find information about your therapy schedule today?" I want to see if they can navigate through the book. Do they know where the book is? Then maybe you get a little bit more generic, "Oh, I feel like you're having a problem remembering what you're going to have to do tomorrow. Is there something you could do to help with that?" Can they navigate to find their calendar? We want them to get used to and acquire the skills and knowledge of their aid that they will need to be successful. Then, you can start writing application goals or engaging in activities that help them apply it. But, it is done in a very structured way.

Role-play can be helpful. I have used nursing staff, other therapists, PTs, OTs, rec therapists in this stage because they understand what we're doing, they know the kinds of questions to ask and how to support someone through a guided interaction. Multidisciplinary care can be really helpful in this application stage, while the person is still in therapy. Then, hopefully, they get to an adaptation stage where they can use it on their own, in their own environment, without any help from you. That might be a little bit of wishful thinking, but hopefully, they get there.

Implementing short-term trials. If you're struggling to figure out how to justify this as part of your services, consider writing goals or implementing activities across these different stages. I find it helpful to implement short-term trials. Again, I have people try out two different systems or aids. I give them time to have one trial phase, where they use a particular system, switch to another system, and then do a debriefing. We would never find a device without a trial period. We would also never select a system without comparing it to other systems to ensure it's the best one. Furthermore, we don't want to select an AAC system for somebody unless they have tried it in their own world and in their own life.

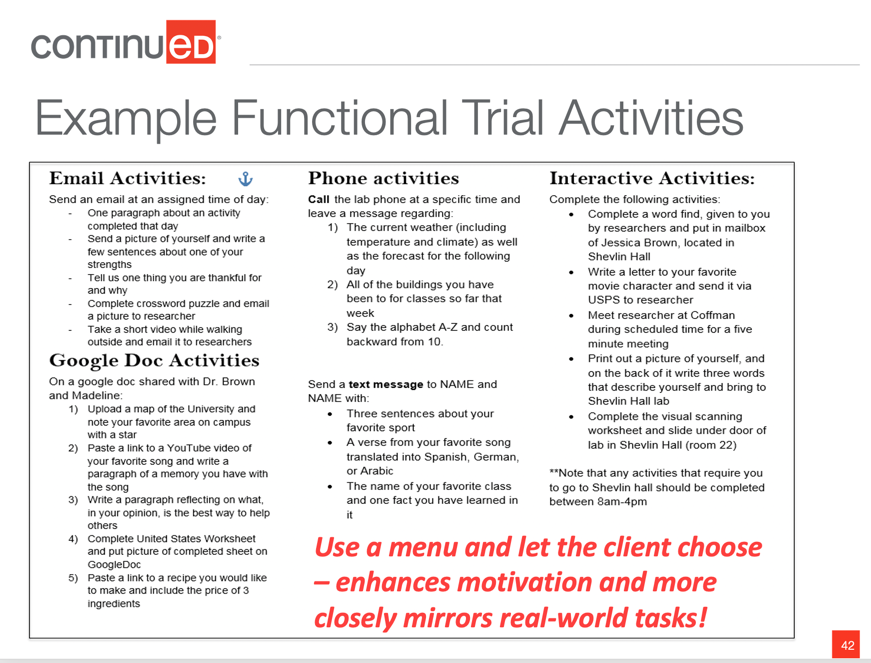

Example functional trial activities. To do the trials, I give my clients a list of tasks to choose from. They select something that they will do over a period of time and they will use the aid that we are trialing to help them complete these activities. I used to choose the activities for my clients, but I have found that there is value in letting the client choose activities. Not only is it going to enhance their motivation to actually complete that task, but it's going to more closely mirror what they might do in their real life. It's not up to me to decide what they need to do to be successful when they leave my office, it's up to them. So I like having a menu available.

Figure 3. Functional trial activities.

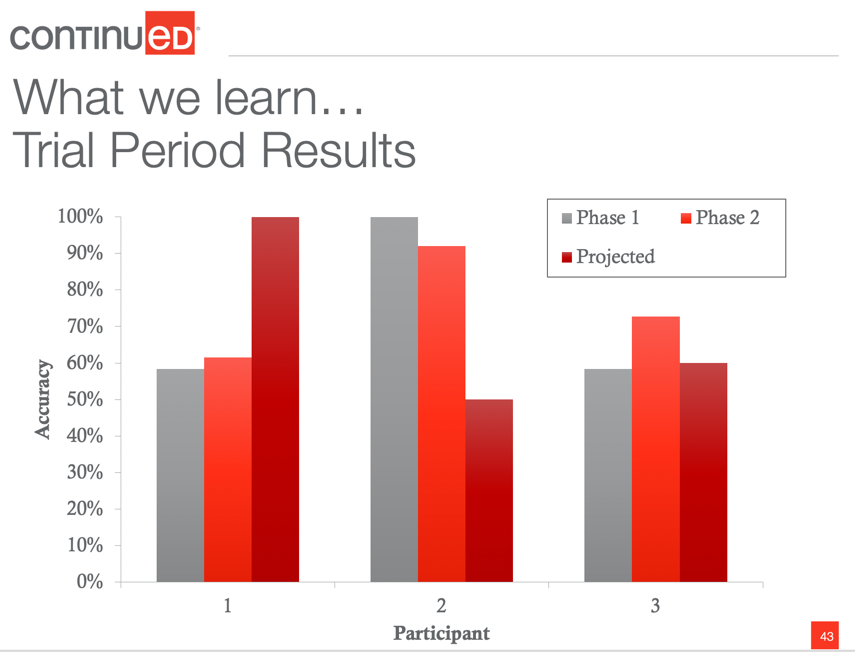

I ask them to select about five things that they will do with the aid over a week-long period. Again, we are doing two trial periods. Below is example data (figure 4) from three different people who showed very different results in their trial periods.

Figure 4. Example trial periods.

The vertical axis is accuracy, or the percentage of tasks they successfully completed during a trial period. The gray represents the first phase, the first system they tried, and the bright red represents the second system they tried. The deep red represents the client's prediction of how many tasks they think they will remember. This question was asked prior to starting the trials. The question gets at that self-awareness piece.

I chose this data because they are three very different profiles. For the first individual, the two different systems were almost identical in their accuracy. So both systems were relatively beneficial. They were 50-60% accurate for completing tasks, which is great. However, comparing that to the individual self-awareness, they projected they would have 100% accuracy. Participant two shows the total opposite. Their self-awareness is poor because they overpredict problems. Their projected accuracy was 50%, but they performed really well when they had these supportive aids. Then, the third person is fairly even for all three.

What ‘we’ learn from trial periods. Collecting this kind of data on our clients can help guide therapy. These trial periods are a type of dynamic assessment. By doing these trials, we get to see how our therapy and how these aids change performance in our client. That's the definition of dynamic assessment, and it's done in an easy way and doesn't require a lot of time.

We are asking the client to mimic independent completion of a task and from that, we can see where the problem is. For example, maybe the person tries some of these different activities, but they really struggle with the details. That tells me something about how I might change that support or how I might help them focus during our therapy activities. Maybe they literally took the system home and never remember to use it or it sat on the table in their hospital room and never looked at it. So, trial periods tell us a lot about where we need to start in terms of either selecting a different type of system or engaging with that system in our therapy. They help determine the next steps for treatment.

Iterative review & adjustments. It is very important to have an iterative review and adjustments. At the beginning of the year, I bought a daily planner and stickers to help me visually with planning. I haven't even opened it and it's almost the end of the year. This planner is obviously not the type of system for me anymore. When I was a student, I used to rely heavily on my planner. But now I have a different life that requires different things. The point is that we can't pick a system with our clients and think it's going to be good forever. We need to keep adjusting and reviewing all of this if we have the ability to in our therapy. It's a continuous training process.

We also may want to consider a hybrid of systems. If a person has comparable use and success with two methods, maybe they use both. One system can be used for certain tasks and the other system may be better for other tasks.

Considerations for Populations of Adults

with Acquired Neurological Disorders

I mentioned at the beginning of this course, that using external aids is going to look very different for a person with dementia versus a person who has a traumatic brain injury. The first factor to consider is whether or not to even use technology. Many of us may automatically consider age as a factor for making this decision. Age-related factors are definitely present, but it is also a bit of a myth. Not all individuals that are aged or considered elderly are unable to use technology. Some of them are very good at technology. I also have some young students in my graduate classes who are terrible at technology. We don't want to make an assumption.

We need to consider cognitive status as well as the individual's premorbid abilities and desires. There is an article written by Kämpfen & Maurer, "Does education help “old dogs” learn “new tricks”? The lasting impact of early-life education on technology use among older adults," that I like to think about in terms of technology. My father was a healthcare administrator for his entire career. He was a CEO and a CFO, and he's done a lot of different things. He could run a hospital so well, but he does not know how to use Skype. I have walked him through how to use it probably 12 different times and he can't seem to figure it out. He is an example of somebody who has a lot of premorbid skills and abilities but may not be a good match for some of these technological ideas because the learning curve is going to be so high for him.

There is research that suggests individuals who are successful with technology or who use technology often, this includes individuals with and without disabilities, usually have characteristics such as younger age, male sex, white race, higher education level, and are married (Gail et al., 2015). This describes a very small subset of our clinical population. Not very many people who we work with are going to match all of these particular characteristics. Although this research can guide us in terms of success or use with high technology aids, we don't want it to bog us down in terms of what considerations we are making with our clients.

Aging and Typical Cognitive Decline

Aging and cognitive decline can also be informative. Interestingly, according to Gitlow (2014), more than 50% of older adults use some type of cell phone or smartphone and a computer. So, over half of those who are in the older population are pretty tech-savvy. However, fewer of them use tablets and e-readers. Many of them actually use technology primarily for socialization activities. For example, texting with grandchildren, calling and emailing support groups, or texting/chatting with their friends. Older adults report a desire to use features such as alarms in their calendars to support their cognition. While barriers include lack of knowledge, negative attitudes, and some of those sensory and physical issues that we talked about. This is for typical aging individuals, which is important to consider as we think about those who have neurological disorders.

Traumatic Brain Injury

The overall idea is that technology could be helpful, but may not necessarily be the best. This is particularly true when we think about the clinical populations that we support. Let's think about traumatic brain injury in general. Obviously, these individuals are going to have acute and chronic symptomatology that would benefit from the use of external cognitive supports. Many of them have the goal of going back to the environments that they participated in before, such as school, work, home life, etc. But the demands of those kinds of environments are incredibly high.

Not only do we need to consider if these supports might work for them, but what it looks like for this population. If we consider the acute stages of TBI, we might use aids that help with orientation (i.e., getting someone oriented times four: person, place, time, situation as well as memory). Memory impairments are not only common in the early stages, but are also persistent complaints from individuals following brain injury. Consider how these aids can support orientation and memory when thinking about content and type of support.

New learning for this population is going to be a struggle. Think about those who might still be in a state of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), meaning they're unable to lay new memories for a period of 24 hours. These aids could be very helpful at that moment. So, immediately in therapy, you could have external aids to help compensate for that inability to learn new information or recall newly learned information. Oftentimes, people with TBI have intact procedural memory or non-declarative memory, but they struggle with the new learning and factual information. In those instances, consider selecting systems that will help them manage those hallmark complaints.

Later in therapy, for individuals with TBI, we should focus more on executive functioning skills. These are the areas discussed earlier that we use to solve everyday problems and engage in the everyday world. In post-acute or chronic outpatient stages, for example, for people with TBI, we can consider supports that are going to hit these higher levels. But early on, it's not appropriate to focus on executive function skills when selecting, implementing, and training external cognitive aids.

Dementia

Traumatic brain injury is obviously something that we hope will allow for rehabilitation. We hope that the impact of the injury is going to be lessened over time. However, we have to think differently when working with individuals with dementia, who are going to have a progressive loss of cognitive functioning at variable rates. Therefore, with this population, using technology is going to be very difficult for this population as time goes on. But we do want to capitalize on tasks that they are good at.

I mentioned that people with TBI are often good at procedural memory and that's absolutely true for people with dementia as well. For example, if there is a magazine or something interesting sitting near a person with dementia, they may rely on that procedural memory to pick it up and flip through it. They may not have very good literacy skills so they are unable to read it, but that innate skill is still intact. Procedural memory is great when it comes to external aids because we can keep these systems ever-present. I take a lot of pictures for clients and I will put their memory books on their walker or their wheelchair. Sometimes I put the picture around their neck or strap it to them because if it's not in their immediate environment they aren't gonna use it. We really want to capitalize on that procedural memory with the availability of these aids. We're not going to teach them when and how to pull out the aid and use it. Their skills are not going to match that level of external aid use. But we want to make them readily available to be used.

We also want to consider things that are very personalized, very simple and primarily focused on orientation for this population. Getting the person to reduce anxiety, recall who they are, where they are, why they are somewhere, are all important.

There is some current literature available on using these memory aids as communication supports. Michelle Bourgeois does a lot of work for individuals with dementia across a variety of different dementia types. She conducted a study on individuals in the earlier stages of suspected Alzheimer's disease. She created memory wallets or little card books that include pictures and words relative to three main topics: family names, biographical information, and the person's daily schedule. They were very orientation-related. They trained some caregivers to use these aids in conversation. Not only were they used for cognitive support, but also as communicative support to enhance potential engagement, back and forth turn-taking, etc. They looked at these conversational sections, or dyads, between these groups of people, and found that the availability and use of the memory books increased communication abilities. There was also increased frequency of expressing factual information. There was less confabulation, more on topic statements, and increased turn-taking when these memory books were present. Additionally, the content was better with less perseveration noted.

The biggest take away from this study is that they actually noticed decreased depression in people with dementia when these memory aids were available for them and subsequently implemented in conversational use. So just the availability of these aids for individuals with dementia is highly impactful. So, I want you to think about some of the flexibility of these systems, not only for cognitive impairments but also other areas that we address as rehabilitation professionals such as conversation and communication.

Summary

In summary, I want to highlight some key takeaways and messages that the literature and clinical experience tells us. First, self-awareness and self-report are very important, but it really doesn't always mirror what is best for the person. We want to think about methods that we can use as clinicians to gain information from a variety of sources to make a really informed decision. We spend a lot of time relying on our own experience in clinical practice, which is excellent, as it is one of the three tenants of evidence-based practice from ASHA.

We also need more research to consider what the best systematic approaches are. I've provided you with some ideas on how to be more systematic and intentional in assessing and implementing these systems with our clients. We want to think about the components that people generally prefer, but also remember that doesn't mean everybody is going to benefit from reminders, for example. This is more of a feature matching process. Meaning, what do you know as a clinician? What does the client think and prefer? What can we rely on from the literature to support our decisions?

We need to consider why we're using external supports. Some populations might have different kinds of needs, so we need to select aids that fit those needs, not only for what their suspected neurological impairments are but also for where they are in their recovery. I am actually doing some research on eye-tracking where I have presented different layouts of daily planners and have altered the text in various ways - highlighted some of it, made some of it bigger, bolded things, changed the font color - to see what we can do to enhance the attention and memory of people with traumatic brain injury to different components of these aids. That's really where I see this literature going and the need for what needs to happen next. We have ideas for how to go about the general process, but we're still missing the particulars about what these aids should look like. That frustrates me because I can't tell you exactly how to create the most evidence-based external cognitive aid right now. But, hopefully, that's where some of the literature is heading so we that have the right option for our client and we've done our due diligence in the design and selection process to promote best outcomes.

Questions and Answers

How do we figure out the design features?

In the world of AAC, we have spent decades trying to figure out how to best design the systems and we still aren't really there yet. AAC is not perfect. We don't have the best language models that are created. Personalization is really key. I spend a lot of time trying to manage the decision as a therapist and a researcher about how much we need to personalize something versus how much time it takes to do that. So, think about some of the methods you can do that are low-hanging fruit. Like I mentioned, maybe starting with a template, but then quickly try to make some of those changes or decisions. Maybe you want to include pictures because that seems to be really important and helpful, and then you ask somebody else to bring in pictures for you and place them in the book. So hopefully, we can do more to specify what the design needs to look like, but figure out ways to decrease the clinician burden because I know that's a really big factor for a lot of people.

How do you use cognitive aids when you're implementing telepractice?

That's a really good question and something that obviously is on everybody's mind right now. I think that particularly for people with traumatic brain injury, telepractice could be a very helpful tool in therapy, and the reason being is it actually allows us to engage with the individual more in their natural context. So you could think more globally about what the goal of the external aid is. Maybe an initial place to start is that you want the person to be able to use their aid to walk them through the steps of accessing your remote technology. Maybe you want them to