Introduction and Overview

In Part two of this five-part standardized assessment series, we're going to focus on the issues of reliability and validity of standardized tests. We're going to define these terms and then discuss the levels of reliability and validity you should look for when selecting a standardized test. When you're thinking about whether or not a test is appropriate, you need to think about psychometric characteristics. We will address diagnostic accuracy next week in Part three of this series. In future seminars, we'll be talking about test content and considerations for dialect and English language learners, as well as the cultural and linguistic load. The purpose of these five webinars is to empower you with the knowledge that you need to be very critical consumers, users, and reporters of standardized tests because we want to make sure that we're getting all and only those children that have a speech language impairment.

As SLPs, when we assess a child, we have four main goals:

- We want children with speech language impairment (SLI) to be correctly identified as having a speech language impairment.

- We do not want children with an SLI to be inappropriately found as not impaired.

- We do not want children who don't have an impairment to be inappropriately labeled as impaired.

- We want to make sure that children without the impairment are found to not have the impairment.

In order to meet these goals, we have to pay careful attention to the quality of the assessments that we're using, and whether these assessments are appropriate for the client that we're testing. A good test is one that demonstrates psychometric adequacy, one that is diagnostically accurate, and one that is appropriate for your client.

Psychometric Considerations

This idea of psychometric adequacy has been discussed for a long time in the field of speech-language pathology. Going back to 1984, McCauley and Swisher conducted a review of 30 preschool tests of language and speech. They developed 10 criteria that they recommended be included in the examiner's manual. These 10 criteria are:

- Standardization sample

- Sample size

- Systematic item analysis

- Mean and standard deviations of test scores

- Concurrent validity

- Predictive validity

- Test-retest reliability

- Inter-examiner reliability

- Test administration procedures

- Special qualifications

Although these criteria were developed in 1984, they are still valid and are used to this day to evaluate the quality of a test.

Standardization Sample

When reading the examiner's manual, according to McCauley and Swisher, there are several pieces of information that should be included. First, you should see a description of the number of sample participants who participated in the standardization. Next, you want to know their geographic residence, as well as their socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status can be measured by income or by the highest level of education of the primary caretaker because education levels and socioeconomic status are highly correlated. Then, you need to have information regarding the "normalcy" of the participants, including any participants who were excluded because they exhibited "non-normal" development or language on both ends of the spectrum (either highly gifted or developmentally delayed).

In an article by Tammie Spaulding, she describes what a norming sample should look like. When we include a lot of children who are not typically developing in the norming sample, that changes the nature of the means and standard deviations that you're getting as a result. As such, you want to think carefully about tests that have large numbers of children with disabilities included in the norming sample if you are trying to capture typical development.

Sample Size

In terms of the sample size, you want at least 100 participants for each age or grade. In older versions of the Goldman Fristoe Test of Articulation, there is a set of norms and they were divided by age and sex. There would be one set of norms for girls age 3.0 to 3.5 and one for boys age 3.0 to 3.5. By the standardization sample size criteria, we would want 100 girls aged 3.0 to 3.5, 100 boys aged 3.0 to 3.5. For every category or level that the test is reporting as score, however they're sub-dividing their scores, in each of those cells you should have 100 participants.

Systematic Item Analysis

Systematic item analysis is the idea that there is evidence of quantitative methods to study and control for both item difficulty and item validity. There are various statistical procedures that can be done. You might see something like split half reliability, or the use of a Cronbach's alpha. In other words, the items that are included in the test are systematically analyzed to make sure that no one item is especially difficult for a particular group of participants, and that the items are, in fact, valid. In addition to quantitative methods and statistical procedures, many times the items are reviewed by a panel of experts to determine validity.

Mean and Standard Deviation of Test Scores

We need to know how the participants did on the test. As we just talked about in the standardization sample, there should be 100 participants in each of the cells. The test manual should also divulge the mean and standard deviation for all of those subgroups. This is important because if the examiner's manual does not indicate whether the test has acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity, the next thing you should look for is whether the means and standard deviations for the different groups are, in fact, different. For example, if the standardization sample included a subgroup of children who had language impairments, you want to make sure that their performance is different from the typically developing children. One way you can do that is to look at the means and standard deviations for a particular age group to see whether the children with language impairments have a different mean and standard deviation than children who are typically developing. Then we can see that the test can put the children into two different groups: one language impaired, one language typical.

Before we go any further, it is important to define and distinguish between two key terms: reliability and validity. Reliability is the degree to which the tool produces stable and consistent results. As an analogy, think about archery and the ability to hit the same target over and over again. Reliability is the idea that you can consistently hit that same target over and over. It doesn't matter what time of the day you're trying to hit the target. It doesn't matter whether the sun is shining or if it's cloudy. Those other variables do not impact your ability to hit that target over and over again.

In contrast, validity is the idea that we're measuring what it is that we think we're measuring. In other words, if we say that we're measuring non-verbal intelligence, are we really measuring non-verbal intelligence if the child has to respond verbally? That test might have questionable validity. It's important to understand that reliability and validity are independent of one another. You can have a measure that has excellent validity, but it's not reliable. Conversely, the measure may be very reliable, but it's not a valid measure of the construct that you're trying to test. Although these two terms are often talked about together, they are different constructs.

Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity is the extent to which the results of a particular test or assessment correspond to those of previously validated assessments for the same construct. In other words, there is evidence that the test categorizes children as impaired or normal similarly as other validated "gold standard" tests. We have other tests that we feel validly assess children's language, and the same group of children would take both assessments and we would compare their performance on the two measures. The caveat is that we have other measures that we think are valid. In our field, especially with speech and language, that's a little bit of a challenge.

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity is the extent to which the test score will predict later performance of the same language or literacy behavior. Even in recent reviews, we still tend to have very few tests for predictive validity, because it requires looking at the same group of children longitudinally over time and reassessing to see how accurate the test is at using early scores to predict later performance. This is the one criteria that most tests still do not have.

Test-Retest Reliability

Test-retest reliability is the idea that if I administer the test today and I administer the test tomorrow, I am going to get the same result. These are often reported as coefficients. When you're looking in the examiner's manual, it should indicate that the test-retest reliability coefficient is .90 or higher. The statistic is an R2 value, and it should state that the R2 is .90 or higher. If you took the test today and tomorrow, it is likely that you would have very little language growth in one day, and therefore your test results should be highly correlated with one another. That correlation should be .90 or higher.

Inter-Examiner Reliability

Inter-examiner reliability means that if I give the test and any of you give the test, we should get the same result. The child's performance should not be dependent upon the person administering the test. The inter-examiner reliability coefficient should be .90 or higher. Again, we want these high correlations because we don't want any of these factors to impact a child's performance on a test.

Test Administration Procedures

In the manual, there should be enough information to instruct you how to give the test in the same way as it was given when they standardized the test. There should be scoring procedures, so that you're scoring it the same way as the children who took the test in the standardization sample. For example, some test manuals are not very clear about whether you can repeat an item. How long do you wait until you repeat an item? How many times are you allowed to repeat an item? Do you repeat the item verbatim or do you need to change the language? Those are things that you, as an examiner, need to know. If I was part of the standardization sample as an examiner, and I gave the test and I read the questions only one time without repeating anything, you might have a different profile of performance than if the examiner repeated those prompts. You want to make sure that you are giving your child the same opportunities to perform on the measure as the children in the standardization sample, and that you are scoring it in exactly the same way. If your administration of the test varies from the standardization sample, that will impact not only the score, but also your interpretation of the score.

Qualifications

I often am asked whether you have to be a speech-language pathologist to be able to give a specific measure. As many of you who work in schools know, our area of expertise often overlaps with the school psychologist, and perhaps the special education teacher. My response is that you need to look in the examiner's manual, which will outline exactly who is qualified to give the test. There may be assessments that are outside of an SLP's normal scope of practice. However, there might be reading assessments that, as a speech language pathologist, we do have specialized knowledge in that area. The takeaway message is to read that manual to make sure that your level of expertise matches up with what the examiner's manual says you need to have.

Improvements in Reliability and Validity

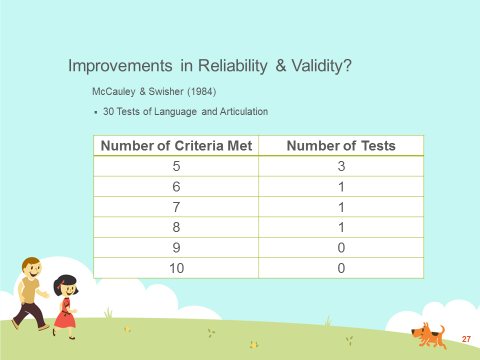

McCauley and Swisher's original study was conducted in 1984. They looked at 30 tests of language and articulation. McCauley and Swisher had 10 criteria that used to measure each test. In Figure 1, you can see the number of tests, and the corresponding number of criteria that each test met. Of the 30 tests that were used, 24 of them met four or fewer of the criteria. Only six of them met five or more criteria. In looking at this data, it is clear that in 1984, we didn't have very good tests.

Figure 1. McCauley and Swisher, 1984.

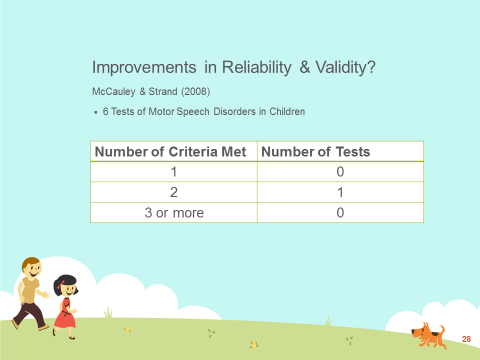

Next, I'm going to present some newer research from 2008. McCauley and Strand looked at six tests of motor speech disorders for children (Figure 2). They found that one test met two criteria, and the rest didn't meet any of the criteria. This suggests that, at least for motor speech disorders, we don't have great tests.

Figure 2. McCauley and Strand, 2008.

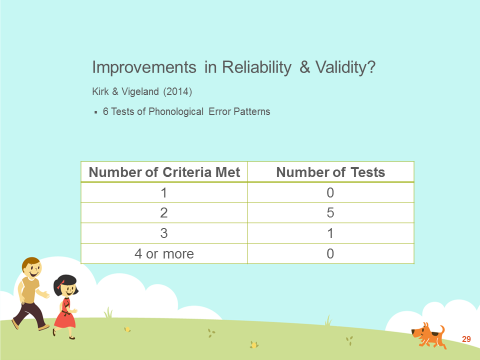

In 2014, Kirk and Vigeland looked at six tests of phonological error patterns. In Figure 3, we see that five of the tests met only two criteria, and one test met three. None of the tests met four or more criteria.

Figure 3. Kirk and Vigeland, 2014.

It is important for all of us who are clinicians to make sure that we are aware of the limitations of these tests. When you look at the Kirk and Vigeland and the McCauley and Strand articles, they used McCauley and Swisher's original criteria. For example, it could be the case that test-retest reliability was .88, so the test did not get the check mark for meeting that .90 criteria. Instead of meeting two criteria, it's possible that maybe this test was close to meeting some of the other criteria. As a clinician, you have to make the judgment about whether it is appropriate for you to use the test or not. That is not an easy question to answer, because as discussed in a previous course, your selection of a test is going to depend on why you're testing in the first place, what information you hope to obtain, and the characteristics of the child that you will be testing. If this test is appropriate for those reasons and the only criteria that the test doesn't meet is test-retest reliability, and the coefficient is .88, then I would probably go ahead and use the test. However, if there are questions about whether this test is appropriate for the child (e.g., if it doesn't allow you to score responses from dialect speakers) then I definitely would become more concerned when the test does not demonstrate acceptable levels of reliability and validity. There are multiple factors that go into deciding, above and beyond whether the test is .90 or higher.

Included in your handout are citations for the three specific articles that I referenced in this course, if you would like to further explore some of those. To review, in 1984, McCauley and Swisher started talking about issues of reliability and validity. In 1994, Plant and Vance were probably the first two to point out that a test can be both valid and reliable, but not be diagnostically accurate, which is problematic. The next course in this series is going to focus on diagnostic accuracy, which include the issues of sensitivity and specificity, and we'll talk about those metrics as they relate to selecting a standardized test.