Introduction

Today’s course is going to focus on some considerations when testing for speech sound disorders. First, we are going to cover issues of reliability, validity and diagnostic accuracy as they relate to speech testing. Then we will get into the coverage of speech testing. In other words, what sounds are tested and in which positions, et cetera. We will think about some dialect issues, and then do a brief case study if time permits.

Testing Considerations

Let’s think about testing considerations, and as I have said over the past four courses, there is no one good test. A good test is one that is psychometrically adequate, diagnostically accurate, and appropriate for your client and purpose of testing. All of those factors combined will help you to decide whether or not a test is a good test for your specific client.

What is a “Good” Test?

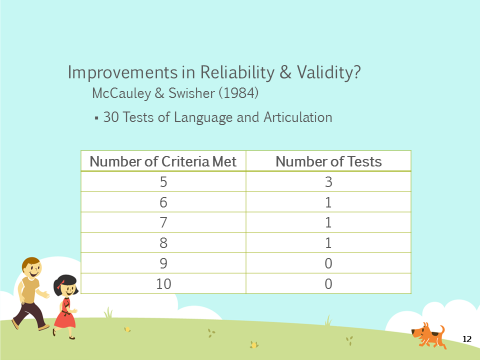

The answer to this question is that it depends on your client, it depends on why you are testing, and it depends on what you are trying to obtain from that testing material. In 1984, McCauley and Swisher had ten criteria for reliability and validity. They reviewed 30 tests of both language and articulation specific to the pediatric population. Figure 1 shows that most of the tests met very few of the criteria.

Figure1. Test improvement in reliability and validity.

Of the 30 tests, six of them met five of more of the criteria, which meant that the rest of the tests met four or few of the criteria. This shows that we didn’t have very good tests in terms of reliability and validity back in 1984. The question you might want to know is, “Have we seen improvements in reliability and validity since that time?”

In 2014, Kirk and Vigeland looked at six single-word tests for children’s phonological error patterns. They had twelve criteria – they had the McCauley and Swisher criteria and included some additional ones. Of the six tests that were reviewed, they found that five of the tests met two of the 12 criteria, one test met three criteria, and none of the tests met four or more.

During a previous course, we looked at language testing and if we compared that data to the speech sound production data, it would seem that we have made more improvements in reliability and validity with respect to language tests. Again, Kirk and Vigeland were looking at phonological error patterns; tests that asses phonological error patterns.

Flipsen and Ogiela (2015) also looked at speech sound production for single-word tests. They included the McCauley and Swisher criteria (i.e., the 10 criteria) as well as seven additional criteria. They found that of those tests, one test met three criteria, three tests met five, four tests met six, and two tests met seven. So for single-word tests, we seem to be doing slightly better in terms of reliability and validity.

Diagnostic Accuracy

If we think about diagnostic accuracy – how accurate the test is at identifying children with an impairment and children who are typically developing - sensitivity and specificity data were only available for six of the 10 criteria in Flipsen and Ogiela’s review. Four of the tests didn’t have any data available. Of the six that had data, only two of them actually gave sensitivity and specificity. For the other tests, Flipsen and Ogiela were able to find means and standard deviations or they were able to extrapolate from the data provided in the exam. There is a manual to determine sensitivity and specificity, but it wasn't explicitly reported. Only two tests actually explicitly gave sensitivity and specificity data. Again, we need to be very cautious and thoughtful about how we're using these standardized tests.

Part of the criteria that Kirk and Vigeland looked at with those six tests of phonological error patterns was sensitivity and specificity data. They found that two of the six tests reported sensitivity and specificity data. However, we don't have four different tests, we only have two different tests because Kirk and Vigeland reviewed some of the same tests. So, of all of the tests that were reviewed, only two actually reported sensitivity and specificity data in the examiner manuals.

Coverage

The next piece, especially for speech sound disorders, is that we really need to be thinking critically about the coverage of the tests. When I first started clinical practice, I never really thought critically about what sounds are being tested and how many opportunities, et cetera. It wasn't on my radar at that time.

Factors

We know that there are several factors that can impact a child's ability to correctly produce a word. Some of the factors that can impact a child's ability to correctly produce a sound include:

- Word familiarity - Words that are more familiar. We are more likely to accurately produce the sounds in familiar words than when we are given words that are not familiar to us.

- Syllabic complexity - Multisyllabic words that have complex syllables are going to be more difficult to pronounce than words that have a simple structure or are single syllables.

- Ability to produce the other sounds in the word - If the word has a lot of sounds that we're not able to produce, that is very problematic as opposed to the word only having one sound that we're not able to produce.

- Stress pattern - English has a pretty complex way of assigning stress. Although most people and linguists would agree that English is a trochaic language (i.e., stress is typically on the first syllable of the word in English), that is not always the case. And it's not always easy to predict why it is “SYMphony” versus “symPHONic.” Stress patterns change in English. The stress pattern will change the actual phonetic segments in that word, and that can impact our ability to produce those sounds correctly.

- Phonetic context - Phonetic context has to do with the surrounding sounds in the word. For example, maybe the child could produce an /s/ sound like in the word ‘sun.’ But if that /s/ is in a consonant cluster as in ‘stick,’ suddenly, ‘stick’ becomes ‘tick.’ The child can say the words, ‘sick’ and ‘sun,’ but not the word, ‘stick.’

All of these factors play a role in whether or not a child can accurately produce a word. There are other factors, but these are the ones that emerge as being particularly problematic for children.

Sounds

When selecting a standardized test, we have to think about whether or not the test developers have taken some of these factors into account. Is the test really determining what the child can and cannot do? In terms of speech sound disorder tests, we need to ask these questions: What sounds are actually tested? In what position of the word? How many opportunities does the child have to produce those sounds? What is the phonetic context of the word? Is it a simple consonant-vowel-consonant construction or is it a more complex consonant-consonant-vowel-consonant-consonant construction? Those are the factors that need to be considered when thinking about the coverage of a test of articulation or phonological processes.

Eisenberg and Hitchcock (2010) looked at 11 tests of articulation and phonology to see what sounds were tested. They looked at word initial sounds and in English there are 22 consonant sounds that can occur in the word initial position. For example, the ‘ng’ sound as in ‘sing,’ cannot occur in the word initial position in English. The researchers wanted to know how many of these 11 tests have tested how many sounds in one phonetically-controlled word? In other words, the stimulus item was a phonetically-controlled word. They found that three tests tested 20 sounds in word initial position, four tests tested 21 sounds of 22, and four tests tested 22 of 22. Again, that's one phonetically-controlled word. So that would be one opportunity to produce that sound in word initial position.

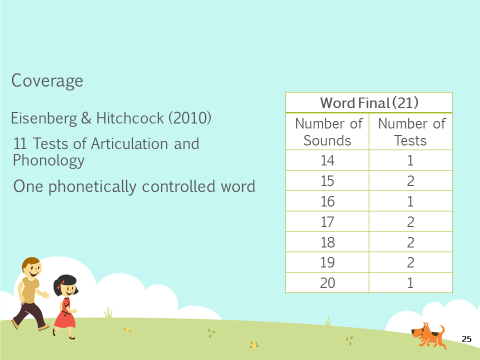

Eisenberg and Hitchcock also looked at word final position. In English, there are 21 sounds that can occur in word final position. Again, this is one phonetically-controlled word, so the child is getting one opportunity to produce that sound. You can see from the chart in Figure 2 that none of the tests tested 21 sounds; they ranged from 14 to 20 sounds.

Figure 2. Coverage of sounds in word final position.

What this research shows is that in most instances, children are only getting one opportunity to produce each of those sounds in one phonetically-controlled word. Remember, we said many factors affect the child's ability to produce the word. And even though the test is controlling for phonetic context, it is also controlling for the syllabic complexity and the stress pattern. What they have not controlled for is word familiarity. So, there is still the possibility that in that one word, that one opportunity, the child might misarticulate the sound because they're not familiar with the word.

Eisenberg and Hitchcock also looked at two phonetically-controlled words in word initial position. Again, none of the tests had 20, 21 or 22 sounds that were tested in two phonetically-controlled words. One test tested 19 sounds in two phonetically-controlled words. So at the most, we're seeing two phonetically-controlled words, and most of the sounds are not being tested, only some of the sounds are getting two opportunities.

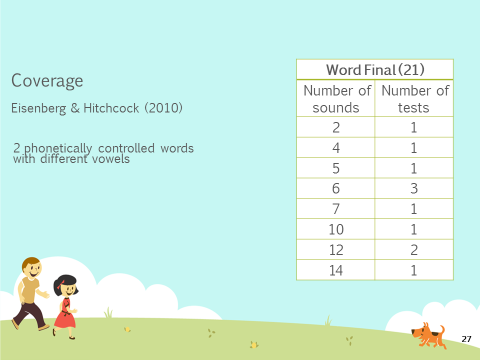

They also looked at it in terms of word final position where there were two phonetically-controlled words with different vowels, so that the phonetic context is different. You're not using the same consonant-vowel combinations. Again, none of the tests tested 15 or more sounds in word final position even though there are 21 sounds that could occur there. Most of the tests are really only testing very few sounds (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Coverage of 2 phonetically-controlled words in word final position.

We have to think cautiously about children. How many opportunities are they actually getting? Are these opportunities phonetically controlled? How familiar are these words to the child? Because it's certainly a possibility, that the child can produce the sound in isolation or if they are given a different word list suddenly they can produce all of the sounds that they just missed on the standardized test. There are so many reasons why a child might not do well on a standardized test and that is something we have to remember, especially when very few tests are reporting diagnostic accuracy values. We want to be very cautious and thoughtful about how we are using these tests.

Diagnostic Accuracy & Coverage

When diagnostic accuracy is combined with coverage, one of the tests that does report diagnostic accuracy is the Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology (DEAP, 2006). This is what they reported in the research articles. The DEAP has one phonetically-controlled word. There are 22 initial and 17 final. For two phonetically-controlled words there were two initial and six final.

The other test is the Clinical Assessment of Articulation and Phonology (CAAP, 2004). When these research articles were written, the CAAP-2 was not yet published. So all of the information that I'm giving you is based on the analysis of the first edition of the CAAP. The first edition of the CAAP does report sensitivity and specificity information and it tests 20 words in word initial and 19 in word final position. That's a one phonetically-controlled word. For two phonetically-controlled words, there are four in word initial and six in word final. In the tests that do have diagnostic accuracy values listed in the examiner’s manual, they don’t actually do a completely thorough test of all of the sounds.

As I said, this research was conducted before the CAAP-2 came out. So, I would encourage you to look at the CAAP-2 examiner's manual to see what kind of information it provides.

What we have talked about in coverage so far is tests of single word production. But as you know, when working with preschoolers, especially those who misarticulate sounds, you are not only thinking about single sounds but the phonological processes that the child might be engaging in and whether those processes are age-appropriate or not.

With phonological testing, we want to think about what processes are tested and how many opportunities the child gets to produce those processes. In 2015, Kirk and Vigeland looked at 11 different error patterns:

- Final Consonant Deletion

- Weak Consonant Deletion

- Cluster Reduction*

- Prevocalic Voicing

- Velar Fronting*

- Postvocalic Devoicing

- Palatal Fronting

- Stopping of Fricatives & Affricates*

- Gliding of Liquids (/l/ & /r/)

- Derhoticization

- Deaffrication

They looked for these patterns in both initial and final position of words. But, some of these patterns will only apply for one of those positions. For example, final consonant deletion only occurs in word final position. It obviously does not occur in word initial position.

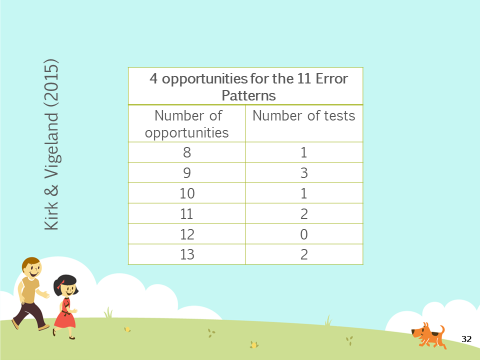

They first asked, “Does the test provide four or more opportunities for each of those 11 error patterns?" Figure 4 shows that children are getting, in many of the tests, quite a few opportunities to produce those 11 error patterns.

Figure 4. Diagnostic accuracy and coverage data for phonological testing on the CAAP.

But, if you look at the research on speech sound disorders as a whole, we know that children with speech sound disorders tend to engage in more idiosyncratic processes. They also tend to use backing and initial consonant deletion with more frequency than typically developing children. I found it interesting that in this article, the researchers did not look at whether the tests tested for these more unusual patterns, which tend to be the hallmarks of children with speech sound disorders. That's just my personal thoughts of, "Well, these patterns are great but what about some of the patterns that tend to be more of a red flag indicating a true disorder such as initial consonant deletion and backing?" Those two patterns tend to be used with much more frequency by kids with speech sound disorders. Again, we just have to be very thoughtful and critical when we're using these tests.

The two tests that they identified were the DEAP and the CAAP-2 that have diagnostic accuracy. In regards to coverage, the DEAP tests nine error patterns. It has less than four opportunities for cluster reduction in word final position, velar fronting in word initial position, gliding of /l/ and /r/, derhoticization and deaffrication. The CAAP-2 also assesses nine error patterns. It has less than four opportunities for cluster reduction in word final position, velar fronting in word initial position, gliding of /l/ and /r/, derhoticization and deaffrication.

Language Variation

Dialect Considerations (Flipsen & Ogiela, 2015)

In Flipsen and Ogiela’s 2015 article that reviewed 10 tests of single-word production, they asked, "Did the test developer discuss the issue of dialect and its potential influence on test scores?" They found that of the 10 tests, four of them did not address the issue at all, which is particularly concerning. Of the six that did address dialect, five manuals simply stated that clinicians need to be aware that dialect could affect scoring and interpretation. My thought is, "Well, it’s nice that you said it, but what do I do as a clinician? How do I score these items? What do I do with it?"