From the Desk of Ann Kummer

The vast majority of pediatric speech-language pathologists (SLPs) evaluate and treat speech sound disorders (SSDs). For these SLPs to ensure that they are providing evidence-based practice, they should be able to answer the question posed in the title of this article: What’s new… in regards to speech sound disorders in children. Fortunately, Drs. Lynn Williams and Elise Baker will answer this question (actually through a total of 20 questions) for all of us in this 20Q article.

Drs. Williams and Baker are uniquely qualified for informing us about the latest in speech sound disorders. They have both authored many articles, chapters, and books on this topic, as their bios will attest.

A. Lynn Williams, PhD, CCC-SLP, is an Associate Dean for the College of Clinical and Rehabilitative Health Sciences and professor in the Department of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her research has focused on the development of a new model of phonological intervention called multiple oppositions that has been the basis of federally funded intervention studies by the National Institutes of Health (NIH); she has authored several articles in a variety of journals, as well as published several book chapters; developed a phonological intervention software program called Sound Contrasts in Phonology (SCIP) that was funded by NIH; authored a book Speech Disorders Resource Guide for Preschool Children; and served as associate editor of Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in the Schools and the American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. She co-edited a book on Interventions for Speech Sound Disorders in Children that was published in 2010 by Brookes Publishing with the 2nd edition to be published next year. Dr. Williams has been a frequent presenter at numerous state, national, and international conferences. She is a Fellow of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and recently served as ASHA Vice President for Academic Affairs in Speech-Language Pathology (2016-2018).

Elise Baker, PhD, CPSP, FSPA is the Course Director of the Master of Speech-Language Pathology program at The University of Sydney, Australia. Her research focuses on speech sound disorders in children including assessment, differential diagnosis, intervention, and innovative service delivery solutions. Dr. Baker is regularly invited by Speech Pathology Australia - the national peak body for speech pathologists across Australia - to present continuing education workshops. She has also been an invited speaker at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association convention. Dr. Baker has authored several articles and book chapters on speech sound disorders in children and co-authored the recent text Children Speech: An Evidence-Based Approach to Assessment and Intervention published by Pearson. Dr. Baker has a passion for supporting clinicians’ conduct of evidence-based practice.

This course offers an overview of many issues related to the assessment and intervention of SSDs in children. It is both interesting and very informative.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Speech Sound Disorders in Children: What's New?

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Describe articulatory and phonological differences in classification of SSD, target selection approaches, and intervention approaches

- Discuss how to use age of acquisition norms to determine eligibility for services

- Describe the Phonological Intervention Taxonomy and outline how it could be used to compare and contrast different intervention approaches

- Identify at least one way to assess the impact of SSD on children's everyday activities and participation

A Lynn Williams

A Lynn Williams Elise Baker

Elise Baker- What are speech sound disorders?

Speech sound disorders (SSD) are a common type of childhood communication impairment involving difficulty with the perception, motor production (articulation) and/or phonological representation of speech impacting overall speech intelligibility and acceptability (International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children’s Speech, 2012). The term speech sound disorder is a theoretically neutral overarching term for a range of different types of speech difficulties of both known and presently unknown origins (Shriberg, 2010), although some authors use the term speech sound disorder to be synonymous with the most common type of speech sound disorder - phonological impairment (also known as phonological delay or disorder). The speech of children with SSD can be difficult to understand because of one or more different types of errors impacting speech sounds, syllable shapes, word lengths or prosody. For instance, specific speech sounds could be distorted, entire classes of speech sounds could be substituted by another class (e.g., substituting all fricatives and affricates with plosives), syllable final consonants could be omitted, or the timing of syllables could be changed.

Different types of intervention approaches are proposed for each type of speech sound disorder.

2. What is the difference between articulation and phonological disorders?

Distinguishing between phonological disorders and articulation disorders is often challenging because articulation and phonology are inextricable constructs (Fey, 1992). Phonology encompasses articulation but expands the scope of speech to incorporate language. As Grunwell (1987) stated, phonological disorders arise more in the mind than the mouth.

Phonological problems are associated with a difficulty learning the phonological system of a language. The difficulty might involve learning which phonemes comprise a language and/or the phonotactic rules governing how those phonemes are distributed in words (e.g., although /ŋ/ is a phoneme in English, phototactically it is not permitted to start a word). Articulation problems are associated with difficulty with the physical production of speech.

3. How are speech sound disorders classified?

Five types of speech sound disorders have been identified - two are considered to have a phonological basis; three an articulatory basis. The phonologically-based speech sound disorders include phonological impairment and inconsistent phonological (speech) disorder (Dodd, 2015). Phonological impairment can be further classified as a phonological delay or phonological disorder (Dodd, 2015). A phonological delay is characterized by pattern-based errors or phonological processes such as stopping of fricatives and velar fronting that should have disappeared for a child’s age (i.e., phonological delay); phonological disorder is characterized by atypical or uncommon pattern-based errors (McLeod & Baker, 2017). Inconsistent phonological (speech) disorder is associated with a phonological planning difficulty and is characterized by inconsistent productions of the same word, in the absence of the prosodic difficulties observed in motor speech disorders. Articulatory-based speech sound disorders include articulation impairment, and two types of motor speech disorders, namely childhood apraxia of speech, and childhood dysarthria (McLeod & Baker, 2017). An articulation impairment (or disorder) is associated with a difficulty clearly producing specific types of speech sounds, such as the distortion of sibilants or rhotics. Childhood apraxia of speech and childhood dysarthria involve difficulties with motor planning/programming (for apraxia) and motor programming and execution (for dysarthria) (van der Merwe, 2009). Shriberg, Kwiatkowski, and Mabie (2019) recently described a third type of motor speech disorder - speech motor delay. Further research is needed to better understand the nature of this new type of motor speech disorder and how it might be differentially diagnosed and treated by SLPs in routine practice.

4. Are phonological problems sometimes actually motor speech difficulties?

Theoretically, we can describe articulation and phonology as two distinct concepts. In reality, however, speech is a combination of both the cognitive abilities to abstract or decipher the phonological system of a language, and the ability to physically articulate speech sounds. This suggests that phonological and motor speech/articulation difficulties can exist on a continuum (Cabbage et al., 2018; McAllister Byun & Tessier, 2016). Ingram, Williams, and Scherer (2017) proposed that speech sound disorders (SSD) be viewed as a spectrum that accounts for the interaction of articulation and phonology. For instance, children with childhood apraxia of speech (a motor speech disorder) can also present with difficulties learning the phonological system. Similarly, children with primarily phonological difficulties can find it difficult to learn how to articulate specific speech sounds. This is why it is important as part of any routine assessment with a child with a speech sound disorder, to determine the individual nature of a child’s speech sound disorder and therefore what might be most helpful for a child. For example, if a child presents with a phonological impairment characterized by velar fronting, but is not stimulable for velar phonemes, the child might benefit from an articulation-based approach to learn how to position the articulations to produce the phoneme before or concurrent with strategies to learn to use alveolar-velar contrasts in words.

5. It has been suggested that children with speech sound disorders are at risk for reading difficulties. Is this true?

Children who have a speech sound disorder can be at risk for literacy difficulties. Indeed, speech sound disorders and dyslexia are considered to be “highly comorbid conditions” (Cabbage, Farquharson, Iuzzini-Seigel, Zuk, & Hogan, 2018, p. 777). The risk and type of difficulty can depend on the type of speech sound disorder. For instance, an increased risk of reading difficulties has been reported in children with phonological impairment (e.g., Hayiou-Thomas, Carroll, Leavett, Hulme, & Snowling, 2017; Preston, Hull, & Edwards, 2013), inconsistent speech disorder (McNeil, Walter, & Gillon, 2017), and childhood apraxia of speech (Carrigg, Parry, Baker, Shriberg, & Ballard, 2016; Gillon & Moriarty, 2007). While the risk of reading difficulties is increased for children with concomitant language difficulties and speech difficulties that persist into the school years (Lewis et al., 2015), literacy difficulties can still emerge following early successful remediation of speech sound disorder (Farquharson, 2015), and in children with an error on one speech sound (Farquharson, 2019). Cabbage et al., (2018) provide a helpful tutorial on the overlap between speech sound disorders and dyslexia, suggesting that reading and speech difficulties can co-occur because both skills rely on children using underlying phonological representations.

6. What are phonological representations and what do they have to do with speech sound disorders?

A theoretical construct that has been used to understand how words are stored in our minds is the underlying phonological representation. Phonological representations are thought of as mental stores of the phonological information comprising spoken words (Sutherland & Gillon, 2005). When children first learn to talk, their representation for words is thought to be underspecified. As children develop, their representations become more detailed. Research on polysyllables has been particularly valuable for understanding this concept of the phonological representation, and the possible underlying nature of phonological impairment. For instance, Masso and colleagues (2017) discovered that children with errors of omission on polysyllables (as opposed to other types of errors such as consonant substitutions) had poorer performance on other measures also thought to rely on underlying phonological representations - including a test of receptive vocabulary, phonological awareness, and phonological processing (e.g., rapid naming and digit span). Why children’s phonological representations are underspecified remains to be clearly understood.

7. How are speech sound disorders assessed?

Speech sound disorders are assessed in two stages - gathering information, then analyzing that information. The information to be gathered can include a child’s case history and speech samples, investigating the child’s body structures and functions that support speech (oral structure and function, hearing, and speech perception), in addition to other areas of communication such as language, voice, and fluency (McLeod & Baker, 2017). It is also valuable to assess a child’s overall psychosocial well-being including day-to-day activities and participation. A thorough assessment would investigate a child’s literacy abilities - either emergent literacy for a child who is yet to start formal literacy instruction or early literacy for a child who has started school. An initial speech sample could be used to establish the presence of a speech sound disorder. The specific type and severity of the disorder would then be determined through strategic speech sampling (Bernhardt & Holdgrafer, 2001; McLeod & Baker, 2017; Strand & McCauley, 2019). Depending on initial observations, this strategic speech sample could focus on one or more different speech elements via one or more different sample methods. The elements could include a range of singleton consonants and consonant clusters across word positions, vowels, and diphthongs, and polysyllabic words with a variety of word lengths and stress patterns, whereas sampling methods could include a single-word sample, a structured connected speech sample (e.g., imitating a series of sentences), a conversational speech sample, stimulability testing of speech sounds that a child has not produced, in addition to repeated productions of the same words to check consistency (McLeod & Baker, 2017). Analysis of the information that has been gathered would then be needed to both determine the type of speech sound disorder, and the potential goals to be addressed in intervention. There are two analysis frameworks: relational and independent. Most analyses are relational, (e.g., phonological process analysis), which compares the child’s productions to the adult target and labels errors in terms of phonological processes. More recent analyses combine independent + relational analyses to provide a more comprehensive description of the child’s sound system. An example of an independent and relational analysis is Systemic Phonological Analysis of Child Speech (SPACS, Williams, 2005) that maps the child’s sound system onto the adult system using phoneme collapses.

8. Are there differences in assessing younger and older children with speech sound disorders?

For young children under the age of 3 years with small vocabularies, there is a need to use a developmentally appropriate assessment tool, particularly given the early connection between lexical and phonological acquisition (Stoel-Gammon, 2011). A valid and reliable assessment protocol for developing phonological systems should contain target words familiar to children aged 24 months or younger (Stoel-Gammon & Williams, 2013). Two tests that are designed particularly for younger children include the Toddler Phonology Test (TPT, McIntosh & Dodd, 2011) and Profiles of Early Expressive Phonological Skills (PEEPS, Williams & Stoel-Gammon, in preparation).

9. What assessment tasks are valuable when trying to differentially diagnose childhood apraxia of speech from phonological difficulties?

When conducting an assessment with a child with highly unintelligible speech, you might suspect that the child has a severe phonological impairment, childhood apraxia of speech, or childhood dysarthria. A comprehensive battery of assessment tasks would be needed to differentially diagnose the child’s type of speech sound disorder. Ideally, the battery would include a single-word speech sample, a diadochokinesis (DDK) task, polysyllabic words comprising words of varying lexical stress, and an assessment of oral structure and function. If you suspect that a child has a motor speech disorder, you could conduct a more in-depth motor speech assessment using a published tool such as the Dynamic Evaluation of Motor Speech Skills (DEMSS) (Strand & McCauley, 2019).

10. Is there value in assessing children’s productions of polysyllables?

Polysyllables—words comprising 3 or more syllables—can provide valuable insight into the nature of a child’s speech sound disorder and risk of literacy difficulties. For instance, preschool-age children with a phonological impairment who have errors of omission (rather than primarily submission errors) on polysyllabic words had poorer performance on measures associated with an increased risk of literacy difficulties (Masso, Baker, McLeod, & Wang, 2017). Difficulty with lexical stress on polysyllabic words in conjunction with a child’s performance on a diadochokinesis task and oral motor examination was reported to be helpful in supporting the differential diagnosis of childhood apraxia of speech from speech difficulties associated with structural abnormalities and childhood dysarthria (Murray, McCabe, Heard, & Ballard, 2015). Given that published speech assessments tend to focus on sampling a range of consonants across word positions in primarily mono and disyllabic words, SLPs would need to check whether the single-word speech sampling tool they routinely use to assess a child, samples an adequate range of polysyllables with varied lexical stress (e.g., banana, computer, caterpillar, rhinoceros).

11. How can we assess the impact of speech sound disorders on children’s everyday activity and participation?

The impact of speech sound disorders on children’s everyday activity and participation can be measured in a variety of ways. SLPs could use an established questionnaire with children such as the Focus on the Outcomes of Children Under Six (FOCUS; Thomas-Stonell et al., 2012). The FOCUS was designed to assess the impact of a child’s speech sound disorder (or communication disorder more broadly) on their everyday activity and participation. The FOCUS is particularly valuable when completed by a child’s parent/carer. The reliability and validity of the FOCUS have been established across a series of studies (e.g., Thomas-Stonell, Oddson, Robertson, & Rosenbaum, 2013; Washington, Oddson, Robertson, Rosenbaum, Thomas-Stonell, 2013; Washington et al., 2013). Another option for assessment is the Speech Participation and Activity Assessment of Children questionnaire (SPAA-C; McLeod, 2004). The SPAA-C was designed to find out from children themselves how they feel about having a speech sound disorder and the impact of a speech sound disorder on their everyday life (e.g., “How do you feel when you talk to the whole class?”). Children can respond by coloring faces that best match their feeling in response to a question (e.g., J K L). The SPAA-C also contains questions for other people in a child’s life (e.g., parents/carers, teachers, siblings). The SPAA-C is readily available at: http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/spaa-c. The reliability and validity of the SPAA-C are yet to be established.

12. I’ve heard a lot recently about the “new developmental norms.” What is that?

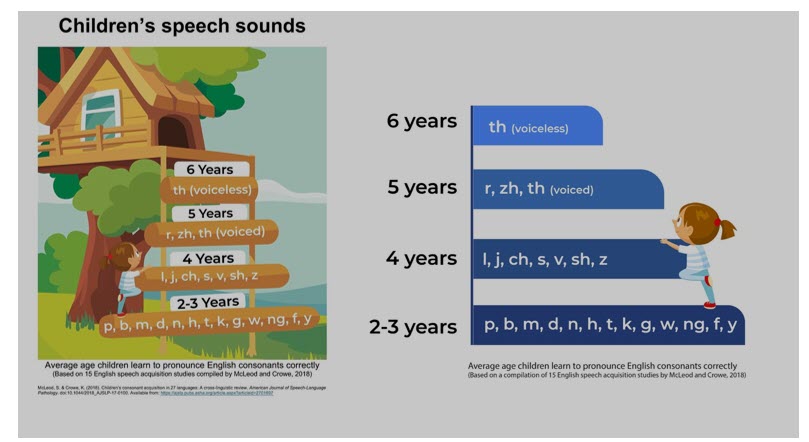

First, there are no new developmental speech acquisition norms! McLeod and Crowe (2018) published an article that aggregated existing norm data across 64 studies from 31 countries to provide a cross-linguistic review of children’s acquisition of consonants in 27 languages. What was interpreted as “new norms” were the infographics the authors published describing their data (see below).

These graphics represent aggregated data that were averaged across these studies to show the age at which 90% of English-speaking children produce a particular sound correctly. Developmental norm studies vary on the age of acquisition because of differences in methodology (e.g., imitated vs spontaneous productions) and in criterion levels (e.g., 50%, 75% or 90% mastery). So the McLeod and Crowe study is useful in providing aggregated data for age of acquisition. Here is a link to more information about the study: https://speakingmylanguages.blogspot.com/2018/11/childrens-consonant-acquisition.html.

Secondly, this confusion brought to light two problems: (1) developmental norm charts were being used incorrectly to determine when a child qualifies for therapy; and (2) developmental norms were frequently being used as a single measure for determining eligibility. A recent 2019 clinical forum in Perspectives on Speech Sound Disorders addressed these problems (cf., Storkel, 2019a; 2019b; Fabiano-Smith, 2019; Farquharson, 2019; Krueger, 2019). Storkel (2019b) summarized best practice guidelines regarding use of age of acquisition norms to determine eligibility for services. These include: (1) consider the range of age of acquisition rather than a single age because of the variability across norm studies and the absence of a diagnostic accuracy for a given cut-point; and (2) integration of normative data with other measures, such as total number of errors, intelligibility, and types of errors. For example, McLeod and colleagues (2012, 2015) have demonstrated that parents report their 4- to 5-year-old children are usually-always intelligible, even to strangers when using the Intelligibility in Context Scale (freely available in over 60 languages http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/ics).

13. How are speech sound targets selected?

There are different target selection approaches, which can be broadly categorized as phonetic (articulatory) or phonemic (phonological). The phonetic approach is the traditional approach that is based on phonetic factors, including developmental norms, stimulability, and consistency of error. This approach assumes there is a motoric basis of sound learning, an ease of acquisition that follows a sequential order of acquisition. Targets that are early developing, stimulable, and produced correctly in at least some positions are prioritized since they are assumed to be easier for the child to learn. The goal is sound accuracy and ease of learning. Conversely, the phonological approach can be informed by various factors such as systemic factors (e.g., the function of a sound within a given child’s sound system), and linguistic factors (e.g., implicational laws and the relationship between marked and unmarked properties in a phonological system with marked or more complex properties implying the existence of unmarked properties) Two phonological target selection approaches are the complexity approach (cf., Gierut, 2001; Storkel, 2018) and the distance metric approach (Williams, 2005, 2010). The goal of both of these approaches is to induce system-wide change in order to achieve the greatest amount of change in the least amount of time.

14. How are speech sound disorders treated?

There are a number of interventions reported in the literature for treating SSD in children. Baker and McLeod (2011) identified 46 approaches for treating phonology-based SSD in a narrative review of 134 peer-reviewed published studies. Only half (n=23), however, had been reported in more than one publication. Given the diversity of SSD, one approach will not fit all children; or even one child all the time. Different approaches are designed to be implemented with different types of SSD, (e.g., articulation impairment, phonological impairment (consistent or inconsistent), childhood apraxia of speech, childhood dysarthria). Some approaches are broader to address co-morbid speech and language impairments or speech and phonological awareness or literacy difficulties. Still, others are designed to be brief, transition approaches to address a particular aspect of sound production (e.g., stimulability or consistency of production) rather than mastery. It is important that clinicians use EBP to select an appropriate approach with a strong evidence base that aligns with the child’s SSD characteristics and that s/he is competent to implement with fidelity.

15. There have been several articles on intervention intensity. Is there a recommended intervention intensity for speech sound disorders?

The intensity of an intervention can influence the success of intervention for children with speech sound disorder. This means that even if you select an intervention approach supported by empirical evidence, it may not work if you underdose or provide the intervention at a diminished intensity (Williams, 2012). Intensity can be conceptualized in four ways: the duration of a session (e.g., 30-minute or 45-minute sessions), the frequency of a session (e.g., 2 x weekly; 3 x weekly), the dose within a session (e.g., 100 production practice trials of intervention target/s), and total intervention duration either measured in the number of sessions or time over which intervention was provided (e.g., 30 sessions; 6-months) (Warren, Fey, & Yoder, 2007). Across the literature on the intensity of interventions for children with speech sound disorders various intensities have been investigated (Sugden, Baker, Munro, Williams, & Trivette, 2018). For instance, for children with phonological impairment, frequent sessions (i.e., 3 x weekly) with a minimum production practice dose of 50 trials in 30 minutes is recommended for children with a moderate-severe phonological impairment receiving multiple oppositions intervention (Allen, 2013; Williams, 2012). Interventions for children with motor speech disorders need to be intense and align with principles of motor learning (see Maas, Gildersleeve-Neumann, Jakielski, & Stoeckel, 2014 for further reading).

16. What is the Phonological Intervention Taxonomy and how can clinicians use it to make intervention decisions?

The Phonological Intervention Taxonomy was created by Baker, Williams, McLeod, and McCauley (2018) to identify the elements that comprise well-studied phonological interventions. Based on a qualitative investigation, Baker et al. identified 72 elements (i.e., building blocks of intervention) through content analysis of meaning statements from published literature on 15 intervention approaches documented in Williams, McLeod, and McCauley (2010). These 72 elements are nested within four main domains (Goal, Teaching Moment, Context, and Procedural Issues). Using this taxonomy, interventions can be compared and contrasted with regard to similarities and differences, as well as the number of elements contained in each approach.

By understanding what makes approaches different from one another, clinicians can select an intervention approach aligned to a child’s particular clinical presentation of phonological impairment. For example, the Stimulability approach is an intervention approach that targets a wide range of stimulable and non-stimulable consonants in supportive teaching moments comprising multiple cues (articulatory-phonetic, phonological, metaphor, and gestural cues) for young children with very limited phonetic inventories and limited speech sound stimulability (Miccio & Elbert, 1986).

17. Why is the Phonological Intervention Taxonomy important?

As noted previously, SSD are diverse and range in the nature and severity of the disorder. Further, children with SSD do not comprise a homogenous population and may exhibit co-occurring challenges with language and/or phonological awareness and literacy. For clinicians to be competent and confident in their management of the diversity of children with phonological impairment, they need to know a range of approaches and the elements comprising those approaches. The Phonological Intervention Taxonomy was developed to make those elements explicit and help promote clarity in clinicians’ understanding of each intervention. Additionally, the Phonological Intervention Taxonomy with its identification of individual intervention elements provides a strategy for examining active ingredients of intervention approaches that contribute to treatment outcomes.

18. I’ve heard a lot about using parents as therapy extenders. Is there research to support this?

There is research to support the involvement of parents in intervention for children with speech sound disorders (Sugden, Baker, Munro, & Williams, 2016). In a review of the empirical evidence on this issue, parents have been involved various tasks such as supporting children with production practice activities at home, collecting data, supporting their children’s self-monitoring skills, and engaging in naturalist play activities (Sugden et al., 2016). Surveys of SLPs practice also suggest that they involve parents. In a survey of 288 SLPs in Australia, 96.4% reported involving parents in intervention in some way, most typically supporting their children in the completion of production practice activities at home (Sugden et al., 2018). It would be important for SLPs to determine if the particular intervention to be used has empirical support for involving parents, as not all interventions have been successfully implemented by parents (Thomas, McCabe, Ballard, & Bricker-Katz, 2018).

19. What do children say it is like living with a speech sound disorder?

The experience of living with a speech sound disorder has been studied by a number of researchers. For some children it can be distressing and isolating, impacting social and emotional wellbeing (McCormack, Baker, & Crowe, 2018). For instance, in a qualitative study of two young men with a history of speech sound disorder and their mothers McCormack, McAllister, McLeod, & Harrison (2012) described some of their experiences as a battle. For instance, Tim recounted that he “would just try and avoid … or avoid specific topics ’cause I wouldn’t know what to say … or don’t know much about the topic or just feel that I might stuff up … just be ridiculed pretty much” (McCormack et al., 2012, p. 151). In a longitudinal case study of a male (BJ) with a severe speech sound disorder, BJ (22 years) recounted the isolation childhood: “Growing up I often felt left out because I wasn’t able to talk with other people, I wasn’t able to tell other people my thoughts or if I needed something. It was heartbreaking because I knew what I wanted to say, but I couldn’t say it. I still feel deeply sad about not talking to others.” (Carrigg, Baker, Parry, & Ballard, 2015, p. 46).

20. What are some of the challenges families face when raising a child with a speech sound disorder?

Parents raising a child with a speech sound disorder have identified several challenges. One challenge is learning how to provide therapy. For instance, in a qualitative study of parents’ experience of completing home practice with their children, one mother Joanne commented that “doing the therapy at home was a bit daunting for me.” (Sugden, Munro, Trivette, Baker, & Williams, 2019, p. 10). Parents have also reported that the experience of raising a child with a speech sound disorder as stressful, but also a journey that can change over time. For instance, Margaret reported that “I think at the start, because we were . . . so worried about him, I think . . . it’s a severe speech sound disorder and we were like, stressed about it, as you are, I think there was a lot of pressure then, and . . . So that was a bit stressful at first but once we could see the progress . . . we’ve been a little more relaxed about it.” (Sugden et al., 2019, p. 11).

References

Allen, M. M. (2013). Intervention efficacy and intensity for children with speech sound disorders. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 56, 865-877.

Baker, E., & McLeod, S. (2011). Evidence-based practice for children with speech sound disorders: Part 1 narrative review. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(2), 102-139.

Baker, E., Williams, A.L., McCauley, R.J., & McLeod, S. (2018). Elements of phonological interventions for children with speech sound disorders: The development of a taxonomy. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(3), 906-935.

Bernhardt, B. H., & Holdgrafer, G. (2001). Beyond the Basics I: The need for strategic sampling for in-depth phonological analysis. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 18-27.

Cabbage, K. L., Farquharson, K., Iuzzini-Seigel, J., Zuk, J., & Hogan, T. P. (2018). Exploring the overlap between dyslexia and speech sound production deficits. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 774-786.

Carrigg, B., Parry, L., Baker, E., Shriberg, L. D., & Ballard, K. J. (2016). Cognitive, Linguistic, and Motor Abilities in a Multigenerational Family with Childhood Apraxia of Speech. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 31(8), 1006-1025.

Fabiano-Smith, L. (2019) Standardized tests and the diagnosis of speech sound disorders. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 58-66.

Farquharson, K. (2015). After dismissal: Examining the language, literacy, and cognitive skills of children with remediated speech sound disorders. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 16(2), 50-59.

Farquharson, K. (2019). It might not be just artic: The case for the single sound error. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 76-84.

Farquharson, K. (2019). It might not be “just artic”: The case for the single sound error. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 76-84.

Fey, M.E. (1992). Articulation and phonology: Inextricable constructs in speech pathology. Clinical Forum: Phonological assessment and treatment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 23, 225-232.

Gierut, J.A. (2001). Complexity in phonological treatment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 229-241.

Gillon, G. T., & Moriarty, B. C. (2007). Childhood apraxia of speech: children at risk for persistent reading and spelling disorder. Seminars in Speech and Language, 28(1), 48-57.

Grunwell, P. (1987). Clinical Phonology (2nd ed.). London: Croom Helm.

Hayiou-Thomas, M. E., Carroll, J. M., Leavett, R., Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2017). When does speech sound disorder matter for literacy? The role of disordered speech errors, co-occurring language impairment and family risk of dyslexia. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(2), 197-205.

Ingram, D., Williams, A.L., Scherer, N. (2017). Are speech sound disorders phonological or articulatory? A spectrum approach (pp. 27-48). In E. Babatsouli & D. Ingram (Eds.) Phonology in protolanguage and interlanguage. Sheffield, UK: Equinox.

International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children’s Speech (2012). Multilingual children with speech sound disorders: Position paper. Bathurst, Australia: Research Institute for Professional Practice, Learning and Education (RIPPLE), Charles Sturt University. Retrieved from http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/position-paper.

Krueger, B.I. (2019). Eligibility and speech sound disorders: Assessment of social impact. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 85-90.

Lewis, B. A., Freebairn, L., Tag, J., Ciesla, A. A., Iyengar, S. K., Stein, C. M., & Taylor, H. G. (2015). Adolescent outcomes of children with early speech sound disorders with and without language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(2), 150-163.

Maas, E., Gildersleeve-Neumann, C., Jakielski, K. J., & Stoeckel, R. (2014). Motor-based intervention protocols in treatment of childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 1(3), 197-206.

Masso, S., Baker, E., McLeod, S., & Wang, C. (2017). Polysyllable speech accuracy and predictors of later literacy development in preschool children with speech sound disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(7), 1877-1890.

McAllister Byun, T., & Tessier, A.-M. (2016). Motor influences on grammar in an emergentist model of phonology. Language and Linguistics Compass 10(9), pp. 431-452.

McCormack, J., Baker, E. & Crowe, K. (2018) The human right to communicate and our need to listen: Learning from people with a history of childhood communication disorder, International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(1), 142-151,

McCormack, J., McAllister, L. McLeod, S. & Harrison, L. J., (2012). Knowing, having, doing: The battles of childhood speech impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 28, 141–157.

McLeod, S., & Baker, E. (2017). Children’s speech: An evidence-based approach to assessment and intervention. Boston, MA:

McLeod, S., & Crowe, K. (2018). Children’s consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A cross-linguistic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(4), 1546-1571.

McLeod, S., Crowe, K., & Shahaeian, A. (2015). Intelligibility in Context Scale: Normative and validation data for English-speaking preschoolers.Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 46(3), 266-276.

McLeod, S., Harrison, L. J., & McCormack, J. (2012). Intelligibility in Context Scale: Validity and reliability of a subjective rating measure. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(2), 648-656.

McIntosh, B., & Dodd, B. J. (2011). Toddler phonology test. London, UK: Pearson Publishers.

Murray, E., McCabe, P., Heard, R., & Ballard, K. J. (2015). Differential diagnosis of children with suspected childhood apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 58(1), 43-60.

Pearson. McNeill, B. C., Wolter, J., & Gillon, G. T. (2017). A comparison of the metalinguistic performance and spelling development of children with inconsistent speech sound disorder and their age-matched and reading-matched peers. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26(2), 456-468.

Clinical Forum on Speech Sound Disorders in Schools. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1)

Preston, J. L., Hull, M., & Edwards, M. L. (2013). Preschool speech error patterns predict articulation and phonological awareness outcomes in children with histories of speech sound disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(2), 173-184.

Shriberg, L. D. (2010). Childhood speech sound disorders: From post-behaviourism to the postgenomic era. In R. Paul & P. Flipsen Jr. (Eds.), Speech sound disorders in children: In honour of Lawrence D. Shriberg (pp. 1–33). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. Shriberg, L. D., Kwiatkowski, J., & Mabie, H. L. (2019). Estimates of the prevalence of motor speech disorders in children with idiopathic speech delay. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 1-28.

Stoel-Gammon, C. (2011). Relationships between lexical and phonological development in young children. Journal of Child Language, 38, 1–34.

Stoel-Gammon, C., & Williams, A.L. (2013). Early phonological development: Creating an assessment test. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 27(4), 278-286.

Storkel, H. L. (2018). The complexity approach to phonological treatment: How to select treatment targets. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(3), 463-481.

Storkel, H.L. (2019a). Clinical Forum Prologue: Speech sound disorders in schools: Who qualifies? Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 56-57.

Storkel, H.L. (2019b). Using developmental norms for speech sounds as a means of determining treatment eligibility in schools. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 67-75.

Strand, E. A. & McCauley, R. J. (2019). Dynamic Evaluation of Motor Speech Skills (DEMSS) Manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul. H. Brookes Publishing Company.

Sugden, E., Baker, E., Munro, N., & Williams, A. L. (2016). Involvement of parents in intervention for childhood speech sound disorders: a review of the evidence. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 51(6), 597-625.

Sugden, E., Baker, E., Munro, N., Williams, A. L., & Trivette, C. M. (2018). Service delivery and intervention intensity for phonology-based speech sound disorders. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 53(4), 718-734.

Sutherland, D., & Gillon, G. T. (2005). Assessment of phonological representations in children with speech impairment. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 36(4), 294-307.

Thomas, D. C., McCabe, P., Ballard, K. J., & Bricker-Katz, G. (2018). Parent experiences of variations in service delivery of Rapid Syllable Transition (ReST) treatment for childhood apraxia of speech. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 21(6), 391-401.

van der Merwe, A. (2009). A theoretical framework for the characterization of pathological speech sensorimotor control. In M. R. McNeil (Ed.), Clinical management of sensorimotor speech disorders (pp.3–18). New York, NY: Thieme.

Warren, S. F., Fey, M. E., & Yoder, P. J. (2007). Differential treatment intensity research: A missing link to creating optimally effective communication interventions. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 70-77.

Thomas-Stonell, N., Oddson, B., Robertson, B., Rosenbaum, P. (2013). Validation of the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication under Six outcome measure. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(6), 546-552, 2013.

Washington, K., Thomas-Stonell, N., Oddson, B., McLeod, S., Warr-Leeper, G., Robertson, B., Rosenbaum, P (2013). Construct validity of the FOCUS (Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six): A communicative participation outcome measure for preschool children. Child: Care, Health and Development. 39(4), 481-489, 2013.

Washington, K., Oddson, B., Robertson, B., Rosenbaum, P., Thomas-Stonell, N. Reliability of the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six (FOCUS) (2013). Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 15(1), 25-31.

Williams, A. L. (2012). Intensity in phonological intervention: Is there a prescribed amount? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(5), 456-461.

Williams, A.L. (2010). Multiple oppositions intervention. In A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R.J. McCauley (Eds.) Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 73-94). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Williams, A. L. (2005). Assessment, target selection, and intervention: Dynamic interactions within a systemic perspective. Topics in Language Disorders, 25, 231 – 242.

Williams, A. L., McLeod, S., & McCauley, R. J. (Eds.). (2010). Interventions for speech sound disorders in children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Williams, A. L., & Stoel-Gammon, C. (in preparation). Profiles of Early Expressive Phonological Skills (PEEPS).

Citation

Baker, E. & Williams, A.L. (2019). 20Q: Speech Sound Disorders in Children: What's New? SpeechPathology.com, Article 20112. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com