Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, School-based SLPs: Are Our Caseloads Really That High, presented by Angie Neal, MS, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List specific requirements for eligibility under the IDEA

- Identify factors that contribute to high caseloads

- Describe consequences of inappropriate identification

Introduction

Thank you for joining me today. I will start by saying that I get it. The title of this course is a little crazy because I know everyone is thinking, "Yes, our caseloads are really that high. I have X number of kids on my caseload, and I am dying here." That being said, this course is designed to help school-based SLPs look at their caseload under the lens of eligibility as per the requirements of the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) to make sure that all of the students that should be on our caseload are and students that should no longer be on our caseload aren't.

Caseload Size Data

First, I want to discuss caseload sizes, which is very interesting because it varies a lot from state to state and even district to district. According to a 2016 study by ASHA, the median monthly caseload was 48, with a range of 31 to 64. ASHA also has a 2020 State-by-State Caseload Guidance document on its website that is available for free. Remember, as I review this data, it is from 2020, so things may have changed by now. But, according to the document, there are 28 states that have no minimum and no maximum number for caseloads. There are three states who do use a formula or have a workload approach. Those three states are Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Indiana. The highest maximum caseload is 80 for Ohio, and the lowest maximum is 30 in Alabama. So, the average for all of the states that participated in the survey was 55. That's a lot of variability.

In a state with a low maximum of 30 or 40 students, it's possible that at different times of the year, you could have more students than at other times because they're pending dismissal. In other words, what I want you to appreciate about these numbers from ASHA is that caseload numbers are never static. They change over the course of the month and the course of a year.

The other thing to consider with these numbers is whether or not the state includes in their caseload numbers the number of students receiving intervention in general education. Also, did they consider caseload numbers and include students who are dually served? Meaning, the SLP serves them but may not be the case manager. We also have to think about how the state defined caseload. What does that word actually mean to them?

Rethinking Caseloads

All of that to say, we need to rethink caseloads because they have remained relatively unchanged over the past decade or more. That is very much the case in my state. Our role as SLPs and our related responsibilities have changed dramatically.

The complexity of the students that we serve has changed. We're now working with students who have feeding and swallowing concerns and students with significant emotional and behavioral needs. There's an increase in autism, with the number of students with autism being 1 in 44.

We've also increased our role in supporting literacy and preventing disabilities through interventions in general education. As a result, we need to think and move towards a workload approach if the SLP is expected to add value to the student's classroom experiences and improve outcomes. In other words, we can't keep doing the same thing the same way because what we do and who we serve have changed.

We, as SLPs, also need to rethink our thinking about caseloads based on a solid understanding of the requirements of IDEA.

Caseload vs. Workload

When thinking about workload and caseload, the reality is that the number of students we serve - that caseload number, the students on an IEP - that's only one small part of the picture. In my opinion, paperwork is honestly more like 60 to 70% of the work I actually do. If we are only counting the actual time spent in therapy, that's not going to reflect the daily documentation, monthly progress notes, administering evaluations, scoring evaluations, writing evaluation reports, writing IEPs, attending IEP meetings and other related meetings, Medicaid billing, all of the ongoing communication with colleagues about a student and the implementation of that IEP. It doesn't reflect the myriad of other tasks we do every day to directly impact the success of the therapy and implementation of the IEP.

Many people ask, "Why doesn't ASHA recommend a caseload?" There are actually several good reasons for that. First, they did recommend a caseload amount at one time. But the states and districts misinterpreted it. Some of them put it as a minimum, and others thought of it as the maximum. Other states actually ignored the recommendation entirely, saying that there's no research to support a specific size caseload. In fact, there isn't any research to support a specific size caseload because the need of the student receiving speech-language services varies greatly. A specific caseload number doesn't take into account that variation. For example, a caseload of 40 students with only speech sound errors is a lot more manageable than a caseload of 40 students who have speech sound disorders, severe disabilities and preschool intervention, and on and on. As a result, the caseload number may actually be dictating the services rather than the student's needs. And that does not support FAPE (i.e., Free and Appropriate Public Education). The bottom line is that your caseload or workload should actually be whatever it needs to be to meet all the needs of all of your students.

With that said, ASHA actually has advocated for a workload approach since 2002. The challenge, however, for districts is they don't like fuzzy numbers. It's much easier for people to allocate personnel to serve X number of students than to allocate personnel to do X number of activities. Not that they can't, but to do so, you must have a good understanding of speech-language pathology and the activities that we do as part of our job.

The Impact of Large Caseloads

When the caseloads are high, and you're seeing a tremendous number of students, what's the impact? First, the outcomes are not as good. Students on smaller caseloads are more likely to make good, measurable progress on functional communication measures than those who are on large caseloads because we may need to serve students in a group, whereas individually may result in better or faster improvements.

Also, student outcomes depend on the SLP's ability to provide services that integrate the educational curriculum. It takes time and collaboration to know what the student's working on and what they are struggling with. It takes time to work with the teacher to figure out how to help support them exactly.

Large caseloads also tend to drive the service delivery amounts that we recommend on the IEP. In other words, "How can I fit this student on my schedule" instead of "What service time does this student need to provide effective services and efficient remediation of a disability?" Not to mention, the more students we have, the more Medicaid billing and paperwork we have to complete, which also takes a lot of time.

If we could go into classrooms and co-teach, that would benefit all students, not just those we serve in the classroom with an IEP. But we can't do that if we have a large caseload or a large workload.

It's also worth mentioning that large caseloads are associated with difficulties in recruiting and retaining qualified SLPs. That's a big piece of it. Additionally, large caseloads limit the time that we have to train and supervise student clinicians, clinical fellows, and other support personnel like SLP assistants and paraprofessionals who may be implementing some of the recommendations of our IEPs.

A Few Points of Consideration within IDEA that Impact Workload

Next, let's look at some important considerations within IDEA that impact the number of students we see and subsequently add to our workload. Specifically, I will discuss the following aspects of IDEA related to:

- Eligibility

- Pre-Referral considerations

- Intervention

- Exclusionary Factors

- Least Restrictive Environment

- Specially Designed Instruction

- Continued Eligibility

Eligibility. Eligibility under IDEA means the student has been identified as having one of the disabilities under the 13 categories of disability that are defined by IDEA. We will discuss what is necessary to document a disability, but for now, the important thing to appreciate is that this is simply a "yes" or a "no." If they do not meet the definition of a disability under IDEA, then that student is not a student with a disability under IDEA.

The student can always be considered as a related service, but that is only if the related service is necessary in order to assist a student with a disability to benefit from special education. This is an important point to understand for two reasons. 1) the student has to have a category of disability other than speech-language impairment. And 2) if speech services are provided to the student, and they're not helping them benefit from special education, then that related service by the SLP is not appropriate. So, we must ask and document how speech is necessary for helping the student benefit from special education. It's not because we "think" they need or want it, but how the student benefits from special education.

Also, a disability does not automatically qualify a child for special education services. This is a huge point of misunderstanding by many people that stems from the fact that in any other setting, children can be served for any area of need without being tied to specific criteria set forth by the IDEA law. Teachers struggle with this because they tend to think that a child needs speech because they can't say a certain sound right, so they need to be enrolled. But that does not equate to a level of disability as defined by IDEA.

It's on us to provide education about how a disability is defined by IDEA and your state. We also need to let teachers and staff know that even with a disability, that's not enough; there are two prongs of disability. The first prong is the disability, and the second prong is the adverse educational impact and, thus, the need for specially-designed instruction. Many people think that there are three prongs, and that is true depending on how you interpret the syntax. Technically, IDEA refers to two prongs: 1) a disability and 2) adverse educational impact, thus the need for specially-designed instruction.

I will address the data collection that you need to support eligibility. But first, let's focus on the term "need." "Need" for special education implies that there's a difference between what they get in special education and what they could get in general education. This is important because if what the student needs can be provided in general education, then they do not need special education.

If there is a disagreement about eligibility, be prepared to share and discuss data that answers two questions, does the child have a disability that adversely impacts educational performance, and do they require specialized services? If the data illustrates that the disability adversely affects educational performance, then they are eligible. If the data does not demonstrate that the disability adversely affects educational performance, then that student is not eligible for services under IDEA. This is why the role of our teachers is so important. They have to be part of the process of gathering this evaluation data. The teacher does not just refer and sit back and wait for the IEP. The teacher who is making the referral has to contribute that data. The teachers who are currently working with the student when you're writing the annual review also need to contribute data to make sure we're documenting ongoing adverse educational impact. We can't do it without teacher data.

Intervention. Intervention in general education can be provided when and if the student is not suspected of having a disability. The key point is they're not suspected of having a disability. That's different for every state. Intervention varies greatly from one state to another and from one district to another, primarily because of how SLP positions are funded. If the SLP is funded 100% through IDEA funds, then 100% of that SLP's time must be dedicated to IDEA-related activities with one exception. That one exception is called the CEIS, or Coordinated Early Intervention Services, which are part of IDEA funds. CEIS are services provided to students in kindergarten through grade 12, but the focus is really on kindergarten through grade three. CEIS is for any child not currently identified as needing special education or related services but who needs support in the general education environment.

Most of the CEIS funds are used for providing professional development. When doing a standard type of intervention, the funds are typically for a very defined period of time, usually six to eight weeks at most. The interventions are designed to meet a very specific need that is determined based on your screenings. Screenings cannot be used to determine whether the child has a disability or not; the purpose of the screening is to identify what intervention needs to target, and those interventions must be evidence-based.

After a period of six to eight weeks targeting a very specific need, the team needs to meet, report on the progress or the lack of progress, and then plan the next steps. For example, what does the next round of intervention need to do? Do we need to ramp it up to a tier three, make it more intensive either by decreasing the number of students in the group that are getting the intervention or increasing the amount of time or number of days, or the amount of time per session?

This does not apply just to speech interventions; it also applies to reading interventions. If you have students who are in intervention for months or years, that is not an intervention; that is a class. They're obviously not targeting the specific needs, and they're not monitoring the progress. So that needs to be changed.

Intervention can and should be counted as part of your workload, especially if special education or CEIS is being used as part of the funding. Again, CEIS includes professional development, which is a great way to provide training to teachers on specific language areas that impact literacy, such as vocabulary, phonemic and phonological awareness, linguistic differences between languages like cultural and linguistically diverse backgrounds and text because our text is written in general American English. These are all areas that we could provide general education teachers with information about. Often, they haven't had instruction, but who better to provide it than the language experts?

When discussing intervention and providing professional development, we must also illustrate to everybody that intervention by the SLP should not be used to supplant explicit and systematic tier-one general education instruction in the five essential components of reading instruction. That includes phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and reading comprehension strategies. For example, we should not be asked to be providing intervention for vocabulary or for phonemic awareness if that's not been provided in tier one. That's an important point because our role in a school is not the primary instructor of that skill. We're not the only people who should be addressing that or have knowledge about that skill. Our role is to be a resource for schools and for interventionists when it's appropriate. In addition, there are many different people in a school who can provide that exact type of support or intervention for phonemic awareness, vocabulary, comprehension, and similar areas. Again, this is when providing professional development on this and collaborating with other school members and team members using those CEIS funds is a good thing.

The key point to remember is that interventions cannot be used to delay or deny an evaluation. If a disability is suspected, start the process outlined by your school, district, or state. Interventions can be provided during that 60-day timeline that's required to complete the evaluation. You can be doing interventions then, but you can't delay or deny an evaluation because you're waiting on interventions to be completed. Actually, doing those interventions during that 60-day window is a great way to collect data through dynamic assessment.

CFR 300.8 Child with a Disability

Let's discuss Prong one, the presence of a disability. According to IDEA, speech or language impairment means a communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice impairment that adversely affects a child's educational performance. Each state differs slightly in this criteria. Before getting into the specifics of defining a disability, because how my state defines it may be somewhat different from how your state defines it, I want to be very clear that you must look at your state's standards of evaluation and eligibility because they aren't the same from one state to another.

Statutes, Regulations, and Guidance

IDEA is a law (a.k.a statute) made by legislatures. IDEA is a statute made at the federal level, meaning the US Congress, the House of Representatives, and the Senate put it in place. State laws are mandated by the state legislature. If you refuse to follow the law, including IDEA, there are civil sanctions and possibly criminal sanctions. Therefore, we have to know the law, and we have to follow the law.

What's the difference between a statute and a regulation? A statute does not and cannot set out all of the details that describe the procedure or the details related to how they apply and enforce the laws. That's where regulations come in. Regulations are usually drafted by departments like the State Department of Education and administrative agencies. Those can be at the federal level or state level, and each has its own area of expertise and its own way of drafting the regulations.

States and other agencies, such as ASHA, can provide further clarification, also known as guidance, on certain topics. If your state has an SLP companion guide, that's considered guidance rather than regulation or statute. The same is true for things that come from ASHA, such as their policy document guidelines for the roles and responsibilities of school-based SLP. That's guidance, not regulation or a statute. Remember, a statute is the law. It is the end all be all.

What happens if regulations and guidance don't align? What if ASHA says one thing, but your state regulations say something else? If guidance and regulations don't align, follow the regulation. State regulations are based on IDEA law. The difference is you get the IDEA statute, and then you have state regulations. State regulations can be added on. They can have additional requirements in the regulation. And that's why there can be a difference between different states' disability criteria. That also explains why in some states, speech can only be a related service, while in other states, it can be a standalone service or a related service.

States, in their regulations, can add on additional requirements, but they cannot limit or reduce the law or what's required under IDEA. So, any additional regulations that are issued by the state must be followed. Again, they may only apply to that state, so we have to know what those are.

In Conducting the Evaluation, the Public Agency Must… (CFR 300.304)

Let's discuss the statutes, these laws, under IDEA for conducting the evaluation. First, we must use a variety of assessment tools and strategies to gather three things: functional information, developmental information, and academic information. We have to gather information about those three areas. We also have to use a variety of assessment tools and strategies to develop the content of the IEP. And, third, we have to document how the disability is related to the student's involvement in the general education curriculum or in the case of a preschooler, participation in developmentally appropriate activities. Again, there are several things in one statute that we need: 1) functional, developmental, and academic information; 2) information that helps develop the IEP; 3) information that's related to the student's progress in general education.

Why is this important? When doing an evaluation, it must be comprehensive. A comprehensive evaluation is made up of four domains of data. The first two relate to documentation of the adverse educational impact. The second two domains support documentation of a disability as a student with a speech-language impairment.

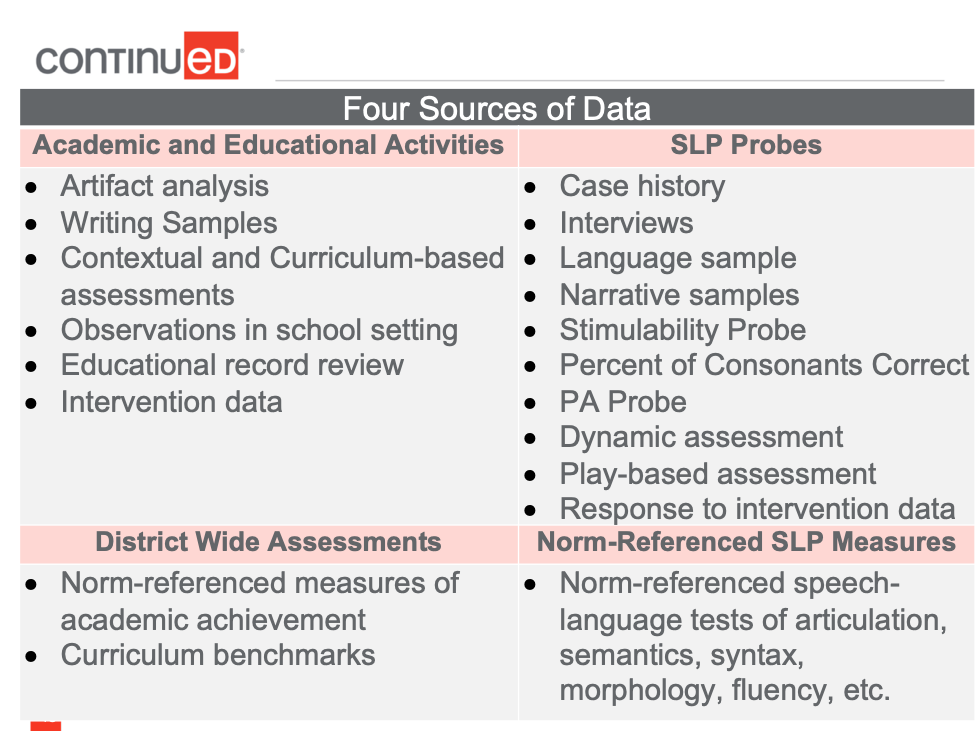

Four Sources of Data

First, let's discuss academic and educational activities (see figure 1). That includes academic activities and contextual tests, which are tests within specific curricular subjects.

Figure 1. Four sources of data.

We have to collect this data to document how a student communicates in the school environment and how the disability or lack of ability impacts educational achievement. This can also include observation of school performance and looking at their functional communication skills in the classroom setting. We can review some of their educational records, class assignments, or work samples. We can also observe the student across different educational contexts, such as the class, the playground, at lunch, et cetera to see what their speech-language abilities look like in real communication tasks. We need that classroom piece to understand what the impact of the disability is in real life. Our analysis of those activities helps support documentation of the adverse educational impact.

District-wide assessments (bottom left of figure 1) include norm-referenced tests that are given periodically to almost every single student to look at academic achievement in comparison to their peers in the school, peers in the district, and peers across the United States. These measures ask the student to actively use written language abilities ad sometimes oral language abilities, which may include vocabulary knowledge, syntactic knowledge, semantic knowledge, morphological, metalinguistic, and literacy-related skills. That said, these measures do not directly assess those components of speech-language ability. Instead, they reflect their ability to activate and apply that language knowledge to academic performance. Again, the data collected on the whole left side of figure 1 support adverse educational impact.

On the right side of the figure are SLP probes. Probes allow the SLP to fully examine the current level of performance in the different areas of language, phenology, morphology, semantics, syntax, pragmatics, voice fluency, and speech-sound disorders. That probe will allow you to unpack all of that. Probes are important because they look closely at the skills along a developmental continuum and stimulability. And answer questions such as, "What's the error pattern?" "What other factors may contribute to a demonstration of that?" The purpose of probe data is to identify if the student exhibits any variations in language and looks closely at dialect and multilingual learners.

We also use a probe to look at the type and degree (i.e., severity) of speech-language impairment, and to inform the development of appropriate goals and recommendations. Probes can include reviewing the case history, the medical history, and developmental history, doing play-based assessments, developmental scales, criterion-referenced assessments, narrative assessments, language samples, and dynamic assessments.

Again, the SLP probes are for stimulability. We're used to stimulability for speech-sound disorders and oftentimes, there is a speech-sound stimulability probe the assessment tools that we use. If you don't have one for your speech-sound assessments, you can use the Miccio stimulability probe. It's free and online. Stimulability is especially important because there is evidence that suggests if sounds are stimulable, then they can be acquired without specially-designed instruction. In fact, research indicates that sounds that are 30% stimulable will continue to come in without us targeting them directly.

What about language? What is our stimulability probe for language? It's your dynamic assessment. That is your stimulability for language.

Finally, are norm-referenced SLP measures. Norm-referenced tests are only as accurate as the least accurate test that you select. In fact, it's actually better to use one test that is well-validated, reliable, and normed for that child's population than it is to use a whole bunch of different tests that are poorly constructed or the normative sample doesn't match that student.

Remember that norm-referenced tests are not contextually based. They don't look at what the student actually knows or can apply in real life. And as a result, they will give an incomplete picture of the student's skills and abilities. Therefore, only using a norm-referenced measure is not enough. It's not enough to get everything required in 300.8 of IDEA. You can't get all the information you need from norm-referenced tests.

In Conducting the Evaluation,

the Public Agency Must… (CFR 300.304)

Continuing on, we can't use one norm-referenced test to say a student has a disability. Many states have cut scores in place for eligibility criteria. In other words, your state may say the student has to be two standard deviations below the mean to be eligible for services. A cut score dictates that eligibility. But, cut scores vary depending on the test. For example, one test may have a disability identified at 1.5 standard deviations while another test identifies a disability at two standard deviations below the mean, and another test states a disability is 2.5 standard deviations below the mean. So, having a randomly assigned 1.5 or 2 standard deviations as being applicable to all tests makes no sense; it's not supported by evidence, and it's not likely to be an accurate determination of a disability.

Using standard deviations to actually diagnose a language impairment doesn't accurately identify language impairment with appropriate sensitivity and specificity, and it's not consistent with IDEA because we also have to consider factors such as whether or not the evaluation is sufficient or comprehensive.

Next, I want to address the phrase "speech-only" evaluations. Speech-only evaluations are a myth. Speech is often seen as a shortcut to special education, but IDEA requires that the evaluation be sufficiently comprehensive to identify all of the child's needs. That means even when there's only a speech-sound concern, if there are educational concerns, all areas must be evaluated or at least discussed and ruled out. Again, that means we have to have a comprehensive evaluation or at least documentation that supports the reason not to have a comprehensive evaluation, including other evaluators. The reason for this is to not delay or deny access to appropriate supports and to make sure that we're presenting the team and family with a comprehensive view of all of the student's needs, as opposed to piecemealing some this year, some next year and some further down the road.

How do concerns about reading and writing impact intervention? They may say the student has to receive the intervention first (actually, that's becoming more of the criteria for a specific learning disability). But we know interventions cannot be used to delay or deny an evaluation, including your evaluation. They can and should occur as part of the evaluation process, as part of that 60 days. That's great data to collect because we are identifying all of the student's needs, and we're not pinning specialized services onto only what the SLP can provide. In other words, we're able to comprehensively support that student and actually reduce the amount of time they should need special education.

Considerations for Assessment Tools

IDEA also requires that we use technically sound instruments. IDEA also requires that the assessments we use are valid and reliable. This may seem straightforward, but it's not because we need to think about the purpose of an assessment tool. The purpose of a standardized assessment is to serve as one piece of data. It is one snapshot of one moment in time and may serve two purposes. One purpose could be to determine if there's a language impairment. Then we must use an assessment that has the capacity to discriminate between students who have a language impairment and those who don't. The only way to do this is to have a tool with appropriate sensitivity and specificity. It has to be 80% or better sensitivity and specificity.

Another purpose might be to determine what the deficit areas are so we know what goals to write. That is not the purpose of standardized assessments. We can't use one standardized assessment to both identify a disability and target the goals. Think about a standardized assessment. How many queries are there, for example, for plural -s? How many queries are there for past tense -ed? How many queries are there for relational vocabulary? How can you say the student has met the criteria for a disability or that this is an area of weakness if they only had two to four items in that particular area? Is missing two out of the four items enough to warrant a goal?

The reverse of this is also true. If the test asks for the plural -s only two times, does that mean that they are actually demonstrating that skill as a weakness in their spoken and written language? A standardized test cannot tell you that because standardized language assessments are decontextualized, which is why we want contextualized information as well. If the student has not mastered that skill in the natural setting (i.e., outside of our test-taking) in conversational language, only then can we say they need to have this skill addressed as a goal. All of this is why assessment tools and strategies, including our SLP probes, are needed to determine the educational needs of the child.

Consequences of Inappropriate Identification of a Disability

If we find a student eligible under IDEA and they don't meet IDEA eligibility criteria, there are lower educational expectations for that student. They get fewer opportunities or less access to the general education program and less rigorous practice, and we are violating that child's civil rights.

As for the SLP, that means higher caseloads. In schools, our funding for special education services is based on criteria from IDEA. In order to receive federal and state funding, we must follow those laws. If we don't, there can be civil and criminal penalties, not just for us but for the school and district, as well. So don't let people or the team bully you into finding a student eligible if there is no data - data that you collected and provided and data that the teacher provided to meet those two prongs of eligibility.

There are also consequences at the state level. The federal office of special education programs monitors students with a disability, how many of them are found to have a disability, and which subgroups are identified as having a disability more so than others. This is referred to as disproportionality. Disproportionality becomes a big deal when the number of students in a certain subgroup exceeds the threshold, and this threshold number varies from state to state. Therefore, we must make sure we are doing appropriate identification.

One state was identified for having too many speech-language impaired students who were white. Again, this is federally monitored, so they had to go back and look at each child's record. In 52% of those cases, the students actually did not meet or continue to meet eligibility. The primary reason cited was the evaluation was not comprehensive enough. In most cases, the SLP was the only evaluator, and therefore, that evaluation was not comprehensive. Another reason the state was cited was that they didn't have enough information from the classroom teacher to document adverse educational impact. Additionally, there was no information provided by the parents in some of the cases, a standardized test was the only measure used to establish eligibility and there were no direct observations of one of the students.

It has also been found that small, rural districts were flagged more often than larger urban districts. That's thought to be attributed to the fact that the SLP in a small rural district may have strong ties to that community. They know those families and may have seen the student's siblings in speech. So they're more likely to enroll the other child as well.

Also, we have all likely had an administrator or a parent say, "You have to take these students. You have to take them. They're not going get anything else if you don't." We've also had teachers who really push for services, even though there is no documentation of adverse educational impact.

Exclusionary Factors

Exclusionary factors are important because the focus of special education is on children with a disability, not children who need additional support. Therefore, IDEA has exclusionary criteria to follow. The team must rule out these factors as the primary cause for difficulties in determining and maintaining eligibility for special education services. Why are these disabilities occurring? We need to look at exclusionary factors before determining eligibility to ensure we're not excluding anyone or including anyone who should or shouldn't receive special education services.

The basic fundamental principle underlying exclusionary criteria is that we can't say they have a disability if they have not been given sufficient, appropriate learning opportunities or if they have other factors that may be the cause. Additional different exclusionary factors include:

- (3)(a)(i) A visual, hearing, or motor disability;

- (3)(a)(ii) An intellectual disability;

- (3)(a)(iii) Emotional disturbance;

- (3)(a)(iv) Cultural factors;

- (3)(a)(v) Environmental or economic disadvantage; or

- (b) not due to lack of appropriate instruction in reading or math.

We must ensure that a lack of appropriate instruction in reading and math is excluded. This is asked on every eligibility document. We also have to ensure limited English proficiency is not an exclusionary factor. Data must be collected to determine that. Think about it this way, especially with the reading. A lot of times, we don't want to be the ones to rock the boat and say, "I'm not really sure if they've received any instruction in phonological awareness." But if you are not documenting that and you've collected it as part of your SLP probes, you have now provided them with a special education service that should've been provided in general education.

Consider economic factors and poverty. Can we say they're language disordered if they've not had the opportunity or exposure to adequate language experiences? This holds true for culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds too. We have to make sure we're not saying it's a disorder if it's related to their dialect or their language.

Environmental or Economic Disadvantage

Environmental disadvantage means school performance related to homelessness, abuse, neglect, and poor nutrition. Economic disadvantage relates to the inability of the family to afford necessary learning materials or experiences. Again, although students may be impacted by economic and environmental disadvantages, the evaluation team has to first determine if that's the primary cause of the difficulties. If an economic disadvantage is the primary reason, we have to provide supports to alleviate that, especially from an oral language standpoint, since oral language is part of the state ELA standards.

Remember, our job is to support students with disordered skills. There are steps that can and should be taken in general education to meet those specific poverty needs before we say it's a disability. To be clear, this is not about excluding students of poverty from receiving additional support; rather, it is ensuring that they're provided the support before we say it's a disability.

There are several important questions that we can ask to help determine this, such as:

- Did the student attend publicly funded preschool (i.e., Headstart, 4k programs, etc.)?

- What additional enrichment or intervention has been provided?

- Does medical history reveal any challenges that may affect school performance (illness, nutrition, trauma or injury, sleep)?

- Has the student changed schools often or attended school sporadically such that typical achievement hasn’t been possible?

- Have there been any significant or traumatic events?

- Are there any variables that may have affected achievement (lifestyle, length of residence in the U.S., stress, poverty, lack of emotional support, guardianship by other adults or agencies)?

Again, these are important considerations because there is usually that general thought of, "They're low SES. What can I possibly do to help with that?" But that thought places the blame and responsibility on the family and disregards the role of the school in providing help and support. Consider this, if all children come to us from strong, healthy, functioning families, it makes our job easier. If they don't, it makes our job more important.

Having worked in Title 1 schools, I can tell you that, more often than not, the district is dictating the instruction. They say, "You have to use this instruction, these strategies, these curriculums across the entire district," without taking into account that there are overwhelming amounts of research that students of poverty have specific needs, especially in developing background knowledge and vocabulary. So, we have to make sure we look at this in terms of exclusionary criteria if we want things to get better.

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

Regarding limited English proficiency, this relates to our choice of assessments. We have to exclude whether or not they've been given that support. We also have to ensure our assessments are not culturally or racially biased. We must also administer the assessment in the child's native language to get the most accurate information.

We also have to consider dialect because the text of what they read in the classroom daily is General American English. There are significant differences between dialect and what that General American English text says. Again, we have to ensure we're not saying there's a disability simply because of these differences. Instead, we need to make sure they're getting the instruction as part of general education.

Adverse Educational Performance

There are some considerations in regard to adverse educational performance. First, you have to support it with data. You have to collect and support with data the impact of adverse educational performance. Educational performance is not limited to academic needs only. We also have to look at social and emotional needs that may impact their progress, as well as their behavior and socialization.

Again, it's not based on grades and test scores. It's not based on how they did on standardized achievement tests. Grades, in and of themselves, are subjective. They're also based on the teacher's observations and subjective interpretations. Teachers give out grades based on many different factors. Some teachers will allow for extra credit work, which will obviously make the grade higher. Other teachers may not allow for extra credit, and that keeps a student's grade lower. Other teachers provide grades based on class participation, good attitude, citizenship, etc. Some teachers may even change or up the grade because they're doing really well and working hard. But that's not an accurate reflection of what that student's actual skills are. So IDEA does not mention grades at all. It doesn't say grades should be a factor in determining whether or not they're eligible for special education services. A child who is making good grades can still need special education support.

IDEA requires that for a student to be eligible for special education support there must be an impact academically, social-emotionally, and vocationally. That said, we can't guess that in 5 to 10 years, there will be a vocational impact for a student. We have to base it on the student's current identified needs. We also have to consider the impact on their involvement and advancement in general education, education and participation with and without students who have disabilities, and their participation in extracurricular and non-academic activities.

Sources of Information to Determine Adverse Educational Impact

Here are the different ways to gather data, all of which help support the determination of adverse educational impact:

- Observation

- Intelligibility

- Phonemic and Phonological Awareness data (probes or norm-referenced assessments)

- Narrative skills

- Play skills (preschool and social-pragmatics)

- Language samples (syntax, morphology, pragmatics)

- Work samples

- Curricular assessments (e.g., social studies tests)

- Teacher checklists/data

- School, district, or statewide assessments

Least Restrictive Environment

Speech therapy is not meant to be long-term. Unless there is a reason that is supported by our data, students should be in gen education. In other words, the least restrictive environment is important enough to be discussed in depth at every meeting because every team member's goal should be for the student to get back to general education and to be in general education as much as possible. So we have to be very thorough and thoughtful about that. And, again, remind people that what we do is tied to federal and state funds. We have to make sure that the student is receiving a free and appropriate education within the least restrictive environment because we have to follow the law.

The second prong discussed earlier was related to specially-designed instruction. That implies that to have a need for special education services, the student has specific needs that are so unique and so severe, they require specially-designed instruction above and beyond anything they could get in general education. That's why it's critical to collect data as part of the assessment that shows the child is not accessing the general education curriculum and their need is so severe that they need specific training by the speech-language pathologist. Also, know that specially-designed instruction is a shared responsibility. Special education teachers also have training and expertise in specially-designed instruction. So we all contribute to this as part of the team.

Dismissal

In order to demonstrate that the student is ready to be dismissed, data has to be collected in three areas:

- The area of disability

- Academic, social, or emotional impact

- And the need for SPECIALLY designed instruction – instruction so severe and so unique that no one else can provide it.

A student who does not have these adverse educational impacts and does not need specially-designed instruction should be considered for discontinuation of services. Again, when we think about the number of students we see and the amount of time that they're served for speech therapy and pulled out of the classroom, we have to ask ourselves, "Does the data support those three things?" If the data does not support it, why are we accepting federal funds to serve them when they don't meet the requirements of the law?

ASHA has a lot of good information on its website about dismissal. ASHA clearly states, "The goal of public school speech-language pathology services is to remediate or improve a student's communication disorder as such that it does not interfere or deter with academic achievement and functional performance."

Dismissal should be discussed at the initial placement meeting and every meeting thereafter, and ideally, it will be a mutual decision. With that, there are some tools and strategies that may help make it a little easier to talk about dismissal.

- Step-down services

- Graphs

- Parent Input

- Classroom/Teacher data

- Does the child continue to have a speech-language impairment?

- How do you know (or how is this documented)?

- Is there an adverse educational impact that results in the need for specialized instruction?

- How do you know (or how is this documented)?

- Does the child continue to have a speech-language impairment?

With step-down services, we want to gradually decrease the amount of services and document that the reduction in services has not impacted their demonstration of skill or their educational performance. We can use charts and graphs. I have my students graph their own progress. Get parent input at least nine weeks prior to dismissal. I have a form letter that I send home that says, "I'm considering dismissal. What are your thoughts? Are there any other things that you want me to be sure to target so that we address any remaining concerns before we go through dismissal? So there are no surprises at the IEP meeting."

Additionally, we need the classroom teacher data. I like to ask the teacher, before the meeting, "Does the child continue to have a speech-language impairment? How do you know?" (You need answers to both questions) I also ask, "Is there an adverse educational impact that results in the need for this specially designed instruction? How do you know (Or how do you document this?)"

Questions and Answers

CEIS is a new term for me. How long has this term been in use?

I have no idea how long that term has been in use, but if you Google "IDEA Coordinated Early Intervention Services," you'll find it.

Can you qualify a student if the team thinks the student may be teased in the future for his single sound artic disorder, but there's currently no impact? I have an elementary student who currently can't say a sound, but there is the possibility of it hindering him socially in middle school.

It has to be based on what you can document. If you can't document that they are teased or that the student does feel bad about it emotionally, then there's no documentation to support it.

Can you clarify what artifact analysis is?

That's just a fancy way of saying to look at their schoolwork, look at their homework, look at their tests. I love to look at tests and see what kind of questions they have difficulty with? What does their spelling look like? What does their writing look like?

Do you have any recommendations for how to gather data or how to assess the social impact?

Social as it relates to speech-sound disorders or social as it relates to pragmatics? Because those are two different things. If you're looking at the speech sound piece, you can't gather data for what might happen or hasn't happened. There's no way to gather that. As far as social for pragmatics, honestly, what we think is only social verbally, you will also see those impacts academically because students who struggle with pragmatics struggle with academic skills like figurative language and comprehension of main ideas because they only focus on the details. They don't get the main idea. So there are things we can look at for that specifically in the area of pragmatics.

How about gathering data for fluency?

A great one for fluency is an inventory with the student. Let them give themselves a rating or even have a discussion with them about that.

In regards to supporting students who are economically disadvantaged, how can we support them? Is that state to state, district to district, or are there specific funds or funding that we can access or connect the family with?

That's a really complicated question because it does vary from state to state, district to district, and school to school. So what I can tell you is that one of the best things you can do is provide professional development for your teachers on the impact of poverty. What does that look like related to the needs in terms of background instruction? What does that relate to in terms of the need for vocabulary instruction? What does that relate to, especially related to phonemic and phonological awareness? It needs to be systematically and explicitly taught, and we could give them great supports for that.

Are reading or writing difficulties alone something that would warrant SLP involvement if it's something that the general ed teacher can address?

If the general education teacher can address it, we can collaborate, but that may not mean that they meet that need of severity related to adverse educational impact. Remember what we do is highly specialized, so we have to make sure that we are doing, not what the teacher could or should be doing, we can help support them. We can provide PD, we can be a resource for them, but they have to need that specialized instruction. And teachers should already be able to provide instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

For students in middle school special ed classes, what happens when they stop being compliant and do not make any more progress?

That's definitely a team decision. But when considering dismissal, especially when I'm looking at progress, the very first thing that I do is I put it on myself. What have I done and how can I document the variety of strategies that I've used? Have I called in another SLP to look at it, are there other possibilities? Again, it's making sure, we have done everything we can to reach that student and remediate the disability. As far as compliance, that's another thing. But I would go back to that reduction in services, slowly going from 60 minutes a week to 30, to 15, to consultative. And what does that look like? Document what that looks like over time.

Abbreviated List of References

Castilla-Earls, A., Bedore, L., Rojas, R., Fabiano-Smith, L., Pruitt-Lord, S., Restrepo, M. A., & Peña, E. (2020). Beyond scores: Using converging evidence to determine speech and language services eligibility for Dual Language Learners. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1116–1132.

Ehren, B. J. (1993). Eligibility, evaluation, and the realities of role definition in the schools. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 2(1), 20–23.

Ireland, M., & Conrad, B. J. (2016). Evaluation and eligibility for speech-language services in schools. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 1(16), 78–90.

Yamasaki, B. L., & Luk, G. (2018). Eligibility for special education in elementary school: The role of diverse language experiences. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 889–901.

Citation

Neal, A. (2022). School-based SLPs: Are Our Caseloads Really That High. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20581. Available at www.speechpathology.com