Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, It's Never Too Late To Collaborate, School Based Therapists And Educators Getting Together, presented by Tere Bowen-Irish, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate various ways of connecting with coworkers regarding student goals and treatment.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze why support may be variable and formulate ideas as to why this may occur.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze how best to collaborate in classrooms and improve their knowledge of curriculum standards for their students.

Introduction

I'm looking forward to this today. It makes my heart happy to be talking about this. I'm genuinely hoping I can offer you some information that either helps you get into classrooms if you're not there yet or helps you tweak things that might not be going well.

I don’t have all the answers for collaboration, but I’m going to offer you a plate of hors d'oeuvres today. Some of what I present will be yummy—you’ll think, “Oh, that sounds great, I will try that,” and you’ll want more. You might contemplate others, maybe even try them, but ultimately, they might not apply to your setting, your style as a therapist, or the environment you’re working in.

School System Delivery for the 21st Century

School system delivery in the 21st century vastly differs from what it was in the late 70s, 80s, and 90s. It all started in 1978, and since then, there has been a great deal of shifting, changing, and reimagining how we contextually treat students through daily, dynamic engagement. You and I both know that offering therapy once a week for 30 minutes or providing a consultation once a month often doesn’t allow us to permeate the child’s environment in a meaningful way, truly. When we’re not present, our services aren't necessarily living on in the classroom—we’re not “haunting” the space, so to speak.

Hopefully, therapy in schools has evolved since 1978. Think about your journey and how much you’ve grown since your first day in school. At the beginning, I was very much a jack of all trades, master of none. That’s where I started. Consider where you’ve expanded your practice from that point—or, for some, where it might have remained the same.

I began my school-based therapy career in Phoenix, Arizona. At the time, I shared a 35-foot Winnebago with two other therapists. We operated on a seven-day schedule for the school, which meant I had access to the van two or three days a week. I would pull up in the fire lane, fire up the generator, go retrieve the student, and bring them out to my van. Inside, I had a swing, a desk, toys—you name it. It was essentially a mobile clinic. If I tried that today, I think I’d probably be arrested, and not just for parking in the fire lane. Looking back, I’ve grown from those early days, and I hope the field has too.

In this 21st-century model of school therapy, there is a constant juggling act. You might work in one school that operates under one set of systems and philosophies, and then enter another school that functions differently. As therapists, we continually keep those balls in the air, navigating differences that can arise not just year to year or month to month, but day to day. And that day-to-day inconsistency can be particularly tough.

That’s why I believe we need practical problem-solving approaches consistent, appropriate, and accessible for therapists. Part of that involves collaboratively utilizing the classroom, working alongside the teacher or even with a social worker, guidance counselor, or other team members.

Sometimes, we forget that we’re not the only ones juggling. Anyone working in education today is carrying a tremendous workload. In theory, collaboration sounds great. But what’s getting in the way of truly inclusive work? What’s preventing the ideal of co-teaching from becoming a reality? That’s what we’ll explore.

Teacher's Reality Vs. Therapist's Reality

Join me in stepping into the teacher's reality for a moment. She’s got a packed classroom—overflowing with energy, needs, demands, and responsibilities. Now, contrast that with the therapist’s reality. Often, we get to pull one student, work with them in a controlled environment, and then deliver them back. I started noticing something whenever I brought a student back into the classroom. I’d say, “Oh, he did great. He’s all set. He’s coming back to you.” And more often than not, the teacher would respond with a look—a roll of the eyes, a grimace, something subtle but telling.

My clinical reasoning would kick in. That moment became a cue for me—an aha. That child might not be doing so well in that classroom environment. Sure, he’ll thrive when I pull him out. But maybe the space where I’m providing the services is not appropriate. Maybe I need to go into the classroom and observe what’s happening. Where are the hiccups? What’s making things fall apart for this child when I’m not there? Because these teachers aren’t loving him like I do, that tells me something important.

There’s also another layer to the reality we live in as therapists. We’re often on the move, traveling from school to school—sometimes eight schools, sometimes ten, maybe even more. Meanwhile, that teacher is in her classroom 6.5 hours a day, every day, with the same kids. If it’s a middle or high school setting, it's 6.5 hours with a rotating roster of students over six or seven class periods.

That puts us in very different operational roles. We can’t juggle every ball in the air for each school, student, and classroom because we often have just an hour. That makes the case even stronger for understanding the teacher’s context, getting into the classroom, and finding collaboration points that make a real impact.

Collaboration

Let's talk about collaboration. And as Dan Siegel says, we’re going to name it to tame it. It’s much more dramatic than it sounds, but for the next 55 minutes, please don’t put on your rose-colored lenses. Let’s talk honestly about how we can shift our paradigms, change our perspectives, and maybe find new ways to flow more effectively as therapists in 2025.

The trouble with specialists is that we tend to think in groups. We stay in our lane because it feels safe. We know our mission, our goals, and our objectives. We’re accomplished. So when we’re asked to bring those same objectives into a different environment—one that we don’t fully control—it can feel scary. I’ve experienced that. I’ve had moments of doubt, of wondering, “Wait, how do I do this?”

But I challenge you to think about the last time you sat in a classroom and truly watched your students—watched them either perform or not perform. Call it therapy. Mark it up for Medicaid or wherever you keep your attendance. Why? Because that’s how you put your hand on the pulse of actual function—of how a student is accessing the curriculum, which is why we’re there in the first place.

It’s easy to push back. “I already have enough to do. No, thank you. I’m done.” The cons are real. Too many schools. Too many staff. Too many schedules. You might think your caseload already takes every ounce of your time. You’re taking paperwork home, writing notes you don’t need. You feel like teachers don’t want you in their space. That it’s their territory, not yours. You don’t want to cross any boundaries. And besides, you think they won’t carry through on what you suggest. You feel like you don’t have the time to plan or generate anything new.

But there are pros. We might find ourselves working smarter—not harder—by integrating activities already planned by the teacher. I remember doing a glyph project with students who were making a scarecrow. I had no idea what a glyph was. The teacher taught me: it’s a visual coding activity based on a rubric. For example, “If you have red hair, give the scarecrow a black hat. If you have brown hair, give it a blue hat.” As we worked through it, I realized it met my objectives for sequencing, inhibition, cutting, and writing—and I hadn’t even had to plan it. I just showed up.

That experience helped me understand why some students seem more challenged in the least restrictive environment. They may do great in our therapy spaces—the little room, the hallway, the gym—but when they get back to the classroom, the nuances of that setting make a huge difference. From our therapist’s perspective, the solution might be simple. If the issue is communication, maybe writing things down could reduce the need for the teacher to call out a name 700 times in 30 minutes. Your presence can model a new way to approach that student. You’re educating the teacher from a therapeutic lens.

There are many barriers to collaboration. Maybe you’re not feeling welcome, seen, or heard. Maybe there’s inconsistency in how different roles are respected in relation to students in special education. There may be territorial issues, lack of motivation, or even fear. But collaboration is about widening the lens. What we do is important—but it should be connected to what others are doing too.

I started working at a school that fascinated me. They chose me, and I chose them, because it was a fully inclusive school—back in the 90s. One of the first things I noticed was that the students didn’t name the special ed teachers as their teachers. Instead, they would say, “I’m Mrs. Stewart’s student,” or “I’m in Mrs. Racum’s class.” They felt like they belonged. They were part of the classroom—not just mainstreamed into art or music as visitors.

There was one teacher I really connected with, a second-grade teacher who said to me one day, “Terry, why don’t you come in and teach my students how to write?” I laughed. I have a personal bias against being a handwriting teacher—it’s just not my thing. But I told her, “Penny, I’d love to help. But I’m going to teach you how to teach them. Because when I’m not here, you need to carry it through.” At the time, we were using the D’Nealian method.

So I’d get them warmed up and ready to write, and then I’d pass it off to Penny. I’d stay in the room, walking around, supporting the students—especially mine—but also anyone else who needed help. I became the CEO of handwriting readiness. Sometimes I’d do therapy for five minutes. Maybe finger flicking, theraband stretches, or other small exercises. I’d say, “Your body’s ready, your muscles are warmed up, you’re alert and ready to write.” Then Penny would take over with the actual lesson. I’d reinforce what she was teaching, spot challenges like far-point copying, or support oral processing of how to form letters. It worked. In one 30-minute session, I reached four of my students, and the teacher got handwriting she could read, meaning she could deliver the curriculum more effectively. That was a win.

There are many articles out there on collaboration. Teachers often say the single biggest barrier is time. They just don’t know when to fit it all in. But we know collaboration is beneficial. When it’s strong and of high quality—with mutual respect and a shared commitment to problem solving—it benefits teachers, therapists, and most importantly, the students.

Laureen Slatter’s Collaboration Framework for School Improvement says we need to consider three things: a common goal, parity in the collaboration, and that collaboration shouldn’t be forced. If we focus on those elements, we begin to reshape our work as a kind of contemporary school reform. Let’s say a teacher says, “I don’t know how to get this student to do paperwork. They’re fidgety and don’t sit still.” That’s our opportunity to consider attention, focus, executive functioning, sensory processing. I might offer warm-up exercises. The teacher might say, “Can you leave some of those with me?” That’s how the sorting and sifting begins.

One thing I often did when writing IEPs in that inclusive school was schedule one session in the classroom and one out. That way I could prime the pump. I’d say to the student, “We’re going to be doing a diorama in your classroom. Let’s plan it together now, so we’re ready.” That helped the child feel prepared and part of the community—not pulled out and missing key group activities.

In another study called Collaboration in Schools: Perspectives of OTs and Teacher Dyads, researcher Morris found that three interpersonal themes were essential: mutual decision-making, effective communication, and respect. I made it a point to go into classrooms saying, “I know nothing about curriculum. How will I learn?” Teachers smiled and welcomed me in. “We’re having a seminar on language arts,” they’d say. “We’ve got a session on science.” I signed up and learned so much. Those courses counted toward my CEUs, and they expanded my understanding of the curriculum.

I still credit Hampton and Shepherd for their work on The Consulting Therapist and later Collaborating for Student Success. They introduced me to the concept of “workload,” which includes not just your caseload, but meetings, travel time, and the daily grind of things like the copier breaking. They also emphasized how we sometimes alienate colleagues by using clinical language. I’ve seen therapists in meetings talk in a way only another therapist would understand. It’s intimidating. Now, I make it a point to speak plainly, as if talking to a parent or layperson. It’s more accessible and practical.

We each have to define our role in collaboration. There’s nothing more gratifying than feeling like part of a community that values your opinion and expertise. Once embedded in a school, I was invited to staff meetings. I knew about every evaluation, every special activity. I got up in a meeting and said, “You’re all doing different things for writing. Some are teaching cursive, others are still printing. That’s a problem.” They agreed and asked me to chair a committee. At first, I was overwhelmed—but I said yes. I brought in Handwriting Without Tears. And what did that do for me as a therapist? It gave me power. It gave me a voice. It made me feel like an educator.

Hampton and Shepherd also emphasized that we, as therapists, are often underutilized. Are we missing opportunities to share our expertise and support student success? One area I see consistently underserved is behavioral challenges. We’re trained in emotional regulation. We understand how self-regulation and emotional control can make or break a student’s day. If we’re part of the team, we can help make a difference.

I’ve joined playground committees, suggested adaptive PE strategies, and even participated in class placement planning for the following year. That allowed me to consolidate caseloads—putting three students in one room instead of spreading them across five. That’s smart work.

And lunch groups? I used to go to the cafeteria because we had students inhaling their lunch in five minutes, which caused trouble. I brought games and a deck of cards. That was therapy. And before long, the other kids joined too. It became a table for connection, inclusion, and shared play—and it all happened in 15 minutes at lunch. It was beautiful.

Each Member Brings Something Unique

Ultimately, each team member should bring something unique to the table. When we consider what we individually add to the overall recipe, it’s important to reflect on what sets our contribution apart. What do you feel you can do better than others? Or maybe it’s not about being better but about bringing a perspective that is simply different, distinct from what others on the team might see or value.

So, what can you offer that no one else can? What do you notice that others might miss? What’s your lens as a therapist? These are the questions I ask myself when thinking about our unique role in the educational setting.

Here are my thoughts on what we, as therapists, contribute in a way that’s both valuable and unique.

- Motor tasks

- Self care

- Self-regulation

- Social, emotional abilities

- Play skills

- Pragmatic language

- Executive functioning

- Participation abilities

- Pre-voc and vocational skills

- Energy conservation

- Specific diagnostic information

- Behavioral consultation

- Sensory processing challenges

- Accommodations and modifications based on age, abilities, and grade expectations.

- Social conventions, receptive and expressive language

It could be motor tasks. It could be self-care. It could support self-regulation and help develop social-emotional abilities. Right now, we’re seeing a group of kids clearly showing the effects of being sequestered during COVID. Their play skills were disrupted, and now they struggle with cooperative group work. They’re missing foundational skills like pragmatic language—speaking to their peers and adults in socially appropriate ways. They’re also having challenges with executive functioning and overall participation abilities.

There’s the shy child, the anxious child. We’re also addressing prevocational and vocational skills, teaching strategies like energy conservation, and providing specific diagnostic information to support teachers and staff. Often, I’d walk into a classroom in September and say to the teacher, “You have Joe Blow this year. He has a diagnosis of autism. Have you worked with a child with autism before?” If they said yes, we’d discuss similarities and differences in behavior and presentation. If they said no, I’d coordinate with the special education teacher, speech-language pathologist, and other team members to ensure we gave this teacher the right tools and specific insights about this particular student.

We also provide behavioral consultation. We look at how sensory processing challenges might interfere with a student’s productivity in the classroom. We help identify accommodations and modifications appropriate for the child’s age, developmental level, and grade expectations. We also consider social conventions, communication needs, and receptive and expressive language. Sometimes it’s as simple as suggesting to a teacher, “When you call on a student, silently count to ten or even fourteen seconds before expecting a response.” That small shift can allow the child enough time to find the words they want to say. It could also be planned so the teacher knows when it’s a good time to call on a particular student, when the teacher is confident the child knows the answer and will feel successful instead of flustered or embarrassed when the words don’t come easily.

Harry Potter Quote

I love this from Harry Potter; it reminded me of being a school therapist.

“Oh yes, if you are any wizard at all you will be able to channel your magic through almost any instrument. The best results, however, must always come where there is the strongest affinity between wizard and wand. These connections are complex. An initial attraction, and then a mutual request for experience, the wand learning from the wizard, and the wizard from the wand.”

This quote has stayed with me throughout my entire career. It’s what’s kept me in therapy all these years. To me, it’s magic—being able to help a child find success, seeing something click, and being part of that transformation. And yes, we can do that one-on-one. Yes, there are moments when it’s entirely appropriate to work sequestered away from the noise and distraction of the larger environment. There are times when that quiet, protected space is not just beneficial, but necessary.

But I’m also saying this: let’s broaden our scope. Let’s help students succeed not just in isolation, but across environments—in their classrooms, on the playground, at lunch, in the community of learners they’re part of daily. That’s my metaphor. That’s my invitation. Let’s be wizards who help our students find the wand that channels their best magic.

Binocular Metaphor: Generalist Vs. Specialist

Sometimes in our practice, we need to take a moment and recognize when we’re looking through our binoculars backwards. When we do, our view becomes narrow, inverted, and focused only on our immediate practice. We may not even realize we’ve got them upside down, and all we see is that tiny field of vision that feels manageable and familiar. But if we’re truly going to join an effort toward more collaboration with the people we work alongside—teachers, administrators, support staff—we need to flip those binoculars around. We need to see the bigger picture.

When we adjust our view, we recognize that we’re not just functioning in isolation—we’re part of a much larger ecosystem. Dropping a pebble in the pond can introduce a ripple of new ideas, new possibilities. Collaboration is that ripple. It's an opportunity to work smarter, not harder, and to expand the scope of our impact.

Sometimes I might say to you, “Think more globally as an educator.” That happened to me when I stood up in a staff meeting and pointed out the inconsistencies in the school’s writing program. I was expressing a concern. But the response I got was, “You don’t like it? Then fix it.” That moment transformed me. I stepped into more of a generalist role in the education setting, and it helped me see the interconnectedness of what we all do.

As you start to integrate more deeply into the school environment, there will be times when someone might say, “Hey, could you help with this?” Or, “Would you mind cutting some things out?” And I’ll be honest—at first, my reaction was defensive. I felt puffy. I thought, “That’s not my role.” But then I stopped and asked myself, “What if it is?” If I can use that moment to pull a student over and say, “The teacher asked us to cut these out for the whole class—can you help me?” I’m doing therapy and supporting the teacher. Everyone benefits. It’s not about giving in or watering down your work. It’s about meeting others in the shared space of education.

Other times, I’ll challenge you to reflect on what you bring to the team as a specialist—your deep knowledge, your unique skill set—and also what you know as a generalist who works across multiple domains. Are you thinking locally, in terms of your workload, your style, your approach? Or are you beginning to think globally, seeing your practice as one integral part of a wider, collaborative whole? That awareness can be a powerful catalyst for growth, connection, and meaningful change.

Collaborator Possibilities

All the possibilities for collaboration span a wide range of professionals—teachers, therapists, ABA specialists, behavioral analysts, parents, doctors, and consultants. Each one has a unique perspective and a valuable role to play. But when we think about the practicalities of regular collaboration, it’s clear that those who are part of the school community daily are most likely to engage in consistent, ongoing dialogue. They’re present. They’re in the environment. They’re seeing the same patterns and responding in real time.

In acute or complex situations, bringing in a doctor, a parent, or an outside consultant to contribute to the planning and intervention process makes sense. Their expertise can be critical. But the real focus—the ball we’re keeping in the air today—is balancing collaboration within the daily school ecosystem. How do we connect and align with the people who are consistently there? How do we create meaningful, functional bridges with the individuals in the student's daily life?

That’s the collaborative space we want to nurture. It’s about building systems and relationships that are responsive, sustainable, and rooted in shared goals—all anchored in the rhythm of daily school life.

Contextual References: Hanft and Shepherd

Hanft and Shepherd emphasized the importance of recognizing contextual stressors for students. They urged therapists to examine the environment a student must navigate every day closely. That means looking beyond just the physical space and considering elements like time demands, social transitions, daily living functions, environmental layout, sensory input, and the level of team support. It requires an honest assessment of what resources and capacities we, as team members, have—and what the student has.

To do that well, we must stop viewing the classroom as a place to pick kids up for therapy and understand it as a living, dynamic environment with expectations, rhythms, and demands. Without that insight, we risk missing the mark.

One morning, a perfect example of this happened when I popped into a classroom to check in on a student. I asked the teacher, “How’s Abigail doing?” The teacher responded, “Well, it’s strange. She doesn't pay attention when I ask the group to be quiet. Everyone else focuses, but she doesn’t seem to notice.”

So I pulled Abigail later that day and practiced some cues with her. I said things like, “Class, please pay attention,” and coached her to fold her hands or sit up a little straighter when she heard the teacher’s voice. The next morning, I circled back to see how it went. The teacher looked confused and said, “What are you talking about? She just sat there and folded her hands while everyone else raised theirs and said, ‘What are you talking about?’”

It turned out that she didn't use verbal cues when the teacher wanted the class’s attention. She held up her hand and made a peace sign. That was her signal. So while I had spent time teaching Abigail how to respond to a verbal directive, I missed the actual cue system in that classroom. I had taught Abigail the wrong thing, not because she wasn’t listening, but because I hadn’t taken the time to learn the expectations of that specific environment.

That wasn’t her failure—it was mine. And I owned that. I told the teacher, “That one’s on me. I’ll fix it. I’ll make sure she knows your system.” Because if we’re truly going to support students, we need to meet them—and their teachers—exactly where they are.

Current Collaboration

- Do we understand roles?

- Can we offer multiple suggestions?

- Do we take time to brainstorm?

- Can we blend roles?

- Can we commit to team decision?

- Can we leave our ego at the door?

- Are we innovative in our communication?

- Do we know each other’s email?

- Do we even have a cubby for mail?

- Do we keep a weekly log?

- Do we use planning time for grades to connect?

- Do we have meetings, gatherings, and special activities on a common calendar?

So, how do we collaborate currently? Do we truly understand our role within the team? Are we offering multiple suggestions when problems arise? Are we taking time to brainstorm and think through possibilities together? Can we blend our roles, stepping outside our silos to support shared goals?

Can we commit to team decisions even when they differ from our initial instincts? Can we set aside our ego—often the hardest thing to do? Are we being innovative in the way we communicate? Do we even know each other's email addresses? Do we have something as simple as a cubby for school mail?

Therapists tell me, “Oh, I don’t need a cubby. I’m only here one day a week.” But I learned a tough lesson when I was covering ten schools. I walked into a classroom one day, and there was a substitute teacher. I said, “Hi, how are you today?” She replied, “Okay.” I told her I was there to pick up James. She said okay, and I took him out for our session. But James was acting differently—he seemed distant and off. I asked if he was alright. And then he started to cry.

He said, “I miss Mrs…” through tears and paused. I didn’t catch the last name. I told him I was sorry and was sure she’d be back tomorrow. And he looked at me and said, “She’s dead.” Again. I could have crawled into a hole. I had no way of knowing. I wasn’t on any school-wide email lists. I had no cubby. No communication system. I was completely unaware of what was going on in this child’s world. That was a turning point for me.

We can’t complain about not being part of the school community if we don’t advocate to be included. So, are we doing that? Do we have a weekly log that we share with other team members? Do we align with the grade-level planning time? Let me tell you a secret: most grades have a common planning time—maybe all the fourth-grade teachers meet on Thursdays during lunch. Ask if you can join that meeting once a month. That’s where you get the real insight into what they’re teaching, what they need, and how you can tie therapy goals into classroom learning.

When you know that spelling is coming up, or that students are working on vocabulary, you can use your sessions to reinforce those same concepts. Maybe you create motor activities that incorporate spelling patterns or word recognition. Suddenly, your therapy isn’t just clinically sound—it’s also educationally relevant. That’s when everyone begins to see the value in what you bring.

Do you have access to a shared calendar for school events, assemblies, or special gatherings? How many of us have driven to a school only to hear, “Oh, sorry, everyone’s at an assembly”—and we had no idea it was happening? It’s happened to me more times than I’d like to admit.

This is about building inroads. We’re coming nearly forty years forward in the evolution of school-based therapy, and part of that is about intentionally sorting and sifting through how we can truly belong. When we do, we don’t just integrate ourselves more fully—we also start to consider what the student is experiencing. We begin to see school through their eyes. And that shift, that perspective, is powerful.

David Sedaris Quote

David Sedaris in, Me Talk Pretty One Day, writes about his experience with speech and language therapy:

My therapy sessions were scheduled for every Thursday at 2:30. It was speech and language pathology. The word therapy suggested a profound failure on my part. I didn't see my sessions as the sort of thing that anyone would want to advertise. Whereas the goal was to keep it a secret, hers was to inform the entire class.”

His teacher, without subtlety, would call out his schedule: “If I got up from my seat at 2:25, she'd say, Sit back down, David. You've got five minutes before your speech therapy session. If I remained seated until 2:27, she'd say, David, don't forget you have speech therapy at 2:30.”

He continues: “On the days I was absent, I imagine she addressed the room saying, David’s not here today, but if he were, he’d have a speech therapy session at 2:30.

Sedaris delivers it with his characteristic humor, but beneath that humor is a real and powerful reminder. For many students, being pulled for therapy can feel like a spotlight on something they’re already insecure about. That experience—of being singled out, of having something meant to support you broadcast in a way that feels shaming—stays with them.

As therapists, we need to remember the impact of our presence, not just our interventions. How we approach pull-outs, communicate with teachers, and protect a student's dignity—all of that matters. This excerpt serves as a meaningful reminder that how can be just as important as the what when it comes to school therapy.

Teacher Buy-In

In a way, we need to walk the talk about who we are and how we can help. How can we get a teacher to buy in? I'm sure that thought has already crossed your mind. As I've been lecturing, there are ways. What I want to do is I want to infiltrate their needs.

- Point of Performance Questions

- More clumsiness?

- Kids that don’t appear to have stamina to complete tasks or even sit up straight?

- Students who seem very weak with grasp patterns for manipulation of objects?

- More clinginess, whining, or heightened emotions?

- Kids who appear more aggressive, rude, and uncooperative?

- Poor focus and attention?

- Students who can’t communicate feelings?

- Poor play skills?

- Disorganized kids?

- Challenges with understanding directions?

Where are they the most frustrated? That’s where I usually begin. I’ll ask a teacher, “What’s bothering you the most about this student?” And what’s so interesting is that often, the response isn’t tied to academic performance. It might be something like, “He’s so clumsy. He can’t return from my desk to his seat without bumping into someone or knocking something over.” That’s a moment where I can say, “Okay, let me help with that.”

Sometimes kids don’t seem to have the stamina to complete a task or even sit upright. Or it’s students who struggle to grasp a pencil—“They hold on too tightly,” or “They complain their fingers ache after one sentence.” When I hear things like that, I begin to turn those frustrations into questions we can explore together.

Are you noticing kids who are struggling to hold their pencils? Are they showing signs of hand fatigue early into writing? What about students who whine, clang, or appear aggressive or rude? How can I support you in helping with self-regulation? Could I join your class during circle time and target those goals as part of my treatment?

We also talk about how to help children communicate their feelings more effectively. I remember offering a handout that showed a range of facial expressions to help reduce verbal overload and make emotional states more accessible. From that idea, we introduced the gel board system. Each student had a small gel board on the right side of their desk, and every morning, they’d draw a face—smiley, sad, angry, or sleepy. As the teacher walked up the aisle, she could instantly see where each child was emotionally before the day even began.

Other times, a teacher is constantly playing referee during playtime because the students have poor play skills. Or there’s a general disorganization and difficulty following directions. Identifying what would help that teacher feel more supported creates a doorway for me to be welcomed into the classroom. It opens the opportunity to model strategies and co-create solutions.

For example, in one case the teacher was frustrated about kids not sitting “crisscross applesauce.” I explained that some kids have tight hamstrings or heel cords, which makes that position difficult. So I introduced the concept of “good sitting” options: crisscross applesauce, long sitting, or side sitting. We called it “Good Situation Sitting.” Then, anytime a child needed a prompt, all the teacher had to say was, “Good sitting—choose one.” It was simple and effective, and it solved her problem without judgment or frustration.

Because I’ve had delays and gaps in understanding the curriculum myself, I began to approach things more directly. I’d say, “Okay, Joey’s coming into third grade. What do you expect him to know when he arrives?” At first, the teacher might look at me a little puzzled. Then I’d follow up with, “What are the skill sets he needs to be ready for this grade level?” That opened the door for me to respond with what Joey was currently capable of and what supports or modifications we were already using.

Then I’d ask, “What’s your exit criteria for Joey? What’s the essential knowledge or performance you want him to have mastered before he leaves this grade?” And that’s when it clicked. Now we had a unified goal. The teacher, the special educator, the speech therapist, the physical therapist, the social worker—everyone working with Joey—could align their efforts. We all knew the basic skill set Joey needed to access his curriculum, and that became our shared focus for the year.

Building Rapport

The other essential part of this work that can’t be overlooked is building rapport. And that takes longer than anyone usually realizes. It can be simple or complex, but the bottom line is that it’s absolutely worth the investment.

I learned little things along the way that made a significant impact. For example, I discovered that teachers often can’t leave the classroom, not even to go to the bathroom. So I started offering, “Do you want me to watch the class for a few minutes? You go take a break, check your messages.” The reaction was often of surprise and gratitude, and off they’d go. I wasn’t doing anything huge—I was being a colleague, a human being, seeing another human being's need.

I made it a point to get to school early. I’d cruise the halls while teachers were already hard at work putting things up, prepping their spaces. I’d poke my head into a room and ask, “How’s our friend doing?” Often, I’d get an earful—an honest, real update that told me far more than any documentation could.

Another strategy that helped build those connections was getting each teacher’s schedule. That way, I knew when specials were happening, when planning periods were scheduled, and when team or grade-level meetings might occur. That allowed me to be more respectful of their time and to find natural opportunities to connect.

Teachers often have websites or digital platforms where they post assignments, test dates, and classroom updates. Accessing those will give you tremendous insight into what’s going on academically and where your therapy interventions might intersect.

I also began asking for open house materials from every grade level. Why? Because those handouts lay out the entire academic year, the expectations, the curriculum, and how the teacher frames their classroom goals. That information is gold for someone who isn’t in the classroom daily.

And don’t forget about teacher newsletters. If a teacher sends a monthly email to families, ask to be included. Those newsletters often contain updates about upcoming units, projects, or challenges in the classroom—and again, that insight helps you align your support more directly with the teacher’s goals.

Small gestures, practical awareness, and intentional relationship-building contribute to your ability to be a trusted partner in the classroom. And once you have that trust, the door to true collaboration swings open.

Creative Problem Solving

Hampton and Shepherd also discuss using creative problem-solving—fitting into an existing time for language arts or math, pinpointing when intervention begins, and again, thinking more globally. Scheduling should be viewed as a systems issue, not your issue. If this feels tough, it’s because it is, but it’s not just about you—it’s about how the system is structured.

Meeting IEP Goals

How do you meet your IEP goals?

- Crafts

- Hands on activities

- Imaginative play

- Recreating stories

- Participation in group projects

- Bringing home the understanding of the curriculum

- Routine and rituals

I’m generalizing here, and I’m not talking about every grade because we often only have an hour. But think about this: is the teacher already doing crafts or some hands-on activity that you could help support? Maybe there’s imaginative play happening, or the class is recreating stories. I used my yoga background, and we had a blast acting out different stories through movement. Or maybe there’s a group project coming up that you can be part of.

I remember having two students in wheelchairs with cerebral palsy for Apple Day. We brought in those apple corers with the rotating handles, and that’s what they did—they peeled apples alongside their classmates to help make apple pies. They were included, they were contributing, and it was meaningful.

Then there are routines and rituals. Ask yourself: Is your student able to grasp and participate in those within six weeks? If not, maybe that becomes an intervention focus for therapy.

Ideal Situation

What’s the ideal situation if you’re starting with this approach? Find one teacher. Just one. Someone who gives you a chance to get your head around the concept. It’s about establishing trust between the two of you, noticing where there are glitches and triumphs. That relationship is your starting point.

One of the things that saved me in the inclusive school I worked in was that consultation was written directly into the IEPs. It was mandated—it had to happen. It wasn’t a maybe-I'll-catch-you-later in the hallway or a quick chat on the sidewalk. It was built in, legally. That structure created a team of like minds with a general understanding of curriculum and a willingness to share overlapping lanes.

How often have we done co-therapy with speech and language pathologists or physical therapists? That kind of teaming can be powerful. I think of Ms. Langless, a kindergarten teacher I collaborated with. Because of our regular consultations, we built something special together. And I didn’t have to plan a thing—she had the themes, and I brought the support.

One of our themes was Johnny Appleseed. We did yoga poses of trees. Half the class stood in tree pose while balancing green, yellow, and red beanbags on their arms and heads. The other half was the wind, blowing around them gently. If a beanbag fell, the wind children collected it, categorized the color, and later graphed it. We also included peeling and chopping apples as sensory and fine motor activities.

Another theme was Knights in Shining Armor. Each child made their shield, which involved drawing and writing. I pulled in Ed Emberley books to support sequencing and drawing skills for the children who wanted to include specific animals or designs. I told Ms. Langless, “We need letter lines on the desks.” That way, when the students referred to models, they could copy near-point. We incorporated cutting and construction paper to create castles. So many objectives were met in the process.

Then there was the theme of Animals and Their Babies. We made nests using shredded Easter basket grass, did animal walks, drew different creatures, and read books like The Mixed-Up Chameleon. Afterward, we talked creatively about which animals to mix up. If someone wanted to be a dog and a cat, they could be a “cog” or a “dat.” Visually, we examined paw prints, matching them to the correct animals, and then we traced our own hands and feet, making connections between the real and the imaginative.

All of these were rich, meaningful activities that came from one strong collaboration. That’s how it starts: with one teacher, one plan, one shared goal. And from there, it grows.

Balancing Collaborative Work in the Least Restrictive Environment

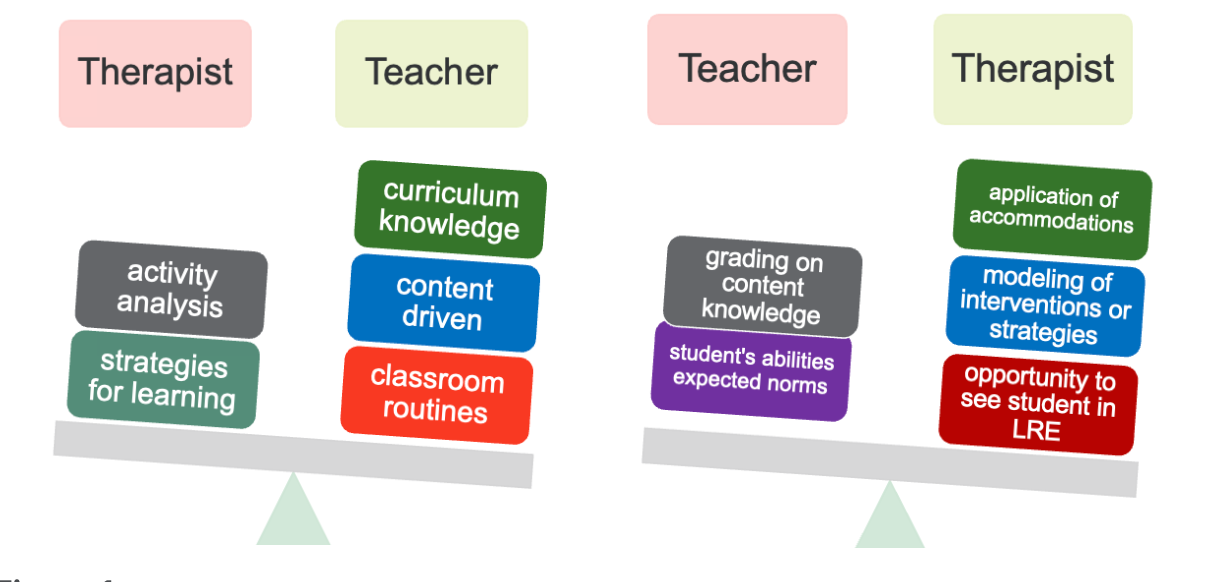

I created Figure 1 because it shows how we're on a seesaw.

Figure 1. Comparing therapist and teacher roles.

Teachers and therapists have to balance collaborative work. The therapist might analyze the activities the teacher asks students to complete and offer strategies to support learning. The teacher knows the curriculum. She's content-driven—or he is—and knows the classroom routines. That’s where our relationship with them begins. Over time, a shift naturally occurs where both the teacher and the therapist are doing their jobs side by side, and the student is the one who truly benefits.

The teacher grades the student based on their content knowledge, abilities, and the expected classroom norms. The therapist, in turn, adds accommodations that help the student meet those expectations. I’m modeling interventions and strategies and observing the student in the least restrictive environment.

Co-teaching, as outlined by Sue Hentz, can happen on several levels. One teach, one support—though I’ll admit, sometimes that feels like I’m acting as an aide, and I don’t always love that. But there are times it serves a purpose. Then there's parallel teaching, where we split the group. Station teaching involves rotating through centers, which can happen at any age and allows us to cruise the room, support our students, and help those struggling. Alternative teaching involves one teacher addressing the larger group while the other pulls a smaller group focused on the same topic. And finally, team teaching—what Mrs. Clara and I did together—that’s when you’re both leading and sharing instruction seamlessly.

As I traveled from school to school throughout my career, I noticed inconsistencies in multiple areas. Where we lacked integration, we also lacked support. And that’s exactly what your handout addresses. It may look more complicated than it is, but I will walk you through it now so it becomes clearer. If you have questions later, my email is listed at the end of the presentation—please feel free to reach out if you want to talk more about collaboration.

Let’s begin. As we all know, every school runs differently. I said that at the start. Each school has its unique structure and its idiosyncrasies. But we don’t have to twist ourselves into Gumby to fit in. We can use this chart to identify what may be missing if we step back. When we put on those binoculars—correctly—we can see the bigger picture and understand where we might be able to fix, repair, or reboot our role.

The top row of the chart outlines the ideal situation. This includes full integration into the educational system, adequate time to consult, plan, and treat, opportunities for professional growth, a supportive environment regarding space and materials, and a salary commensurate with other staff. When these elements are in place, a therapist is more likely to deliver successful treatment, assessment, and consultation interventions and can be an integral part of the educational team.

The “X” marks on the chart indicate what’s missing. The element listed at the top is absent if the “X” is in a particular column. For example, if integration into the educational system is missing—meaning the therapist isn’t part of scheduled meetings, isn’t getting student information promptly, and is being left out of referrals and communications—then the result is an overload of work, wasted time, and miscommunications. We lose valuable treatment time, and we end up scrambling for space and support.

The next row down deals with time. If we lack adequate time to plan, treat, and consult—and don’t have clear entrance or exit criteria for therapy—we end up with students staying on caseloads longer than necessary. Therapists are forced to cancel or delay treatments to meet administrative requirements. That’s why I often say to parents at our first IEP meeting, “Your child’s time in therapy may be short. Their nervous system is malleable and may only take six months or a year.” I say that to set realistic expectations. This isn’t a clinic—it’s an educational setting.

The third line covers professional growth and collaboration. Suppose there’s no opportunity to expand your skill set, no support for collaboration, and no integration of educational topics into your work. In that case, you may feel overwhelmed or confused about your role. You can’t keep up with current trends and get stuck operating with outdated practices from decades ago.

Environmental factors are next: space, materials, supervision, and travel reimbursement. If these are lacking, therapists may burn out. We spend our money on supplies, drive between schools without mileage compensation, and work without supervision or peer support.

And finally, salary. Are you on the same pay scale as teachers? Do you get the same benefits and prep time? I discovered that full-time teachers were getting three 45-minute prep periods per week. I asked, “Why am I not getting that?” And, to be fair, the administration said, “You’re right.” When I finally got that planning time, I stopped taking work home as often. We have to advocate for ourselves.

If any of these pieces are missing, it can lead to resentment, a lack of respect for administrators, and even overridden treatment decisions. That’s why it’s so important to step back, look at the system as a whole, and advocate for the changes that support our professional responsibilities and ability to help students succeed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we’ve covered a lot of ground—considerations for collaboration, school system delivery, and the many ways therapists can integrate meaningfully into the educational environment. I can hear the passion in my voice—it’s still there. I hope you’ve found something in this that speaks to you, is helpful, and is applicable to your setting and circumstances.

I’ll leave you with a few final questions to reflect on.

As a therapist, do you have time to talk with teachers, or are you always on the run? Is that all right with you?

Are you, as a school-based therapist, a contributing member to the orchestra of that classroom? I once wrote an article about this—it’s in your bibliography. In it, I explored the idea that the teacher is the conductor. So I ask you: do you feel that the conductor is satisfied with their relationship with you?

And finally, do the teacher and the other staff truly realize what therapists can offer? This is not just for children with IEPs but also for all the students in the classroom who may benefit from differentiated support and strategies.

In the 21st century, shouldn’t we build bridges instead of walls?

Thanks so much for coming.

Exam Poll

1)What challenge is illustrated by the contrast between a therapist’s and a teacher’s daily routine?

2)According to the Tichenor study, what did teachers identify as the single largest barrier to effective collaboration?

3)According to Lorraine Slater’s framework for school collaboration, what are the three necessary elements that support effective collaboration?

4)Which of the following is an example of a unique contribution a therapist may bring to a school team?

5)What is one likely result when therapists are not given adequate time to manage and treat their caseload?

Questions and Answers

Some districts require therapists to specify in the IEP whether services will be provided in the special education environment or the classroom. Do you have suggestions for navigating this?

Yes, I do. If I see the student twice a week for 30 minutes, I may list one session in and one out. If I’m only seeing the student once a week, I would mark it as “in.” And if I’ve contracted with the teacher to be in the classroom, I make sure that’s clearly communicated. If I’m still having difficulty getting into the room, I might list it as “out,” but then speak with the teacher and ask, “Are there times during the month that I could come in?” Even starting just once a month while the student is present can build that connection. Marking it as “out” doesn’t mean the opportunity is lost.

Do you have any suggestions for fieldwork students who feel apprehensive about addressing behavioral or mental health issues so they can feel more empowered to collaborate with teachers and support students?

As a fieldwork student, you're taking cues and guidance from your supervising OTP. You already have a skill set—it just takes honing. If you attend a meeting where behavior is discussed, listen and think, “Where would therapy fit in here?” For example, if they’re saying a student is extremely fidgety during circle time, maybe seating needs to be rearranged or there’s an opportunity for discreet teacher cueing, like a nonverbal hand signal. It’s a give and take. Take notes during those meetings and check in with your supervising therapist afterward to get their take.

My biggest complaint is that I often feel like I don’t have enough time to collaborate with teachers.

I hear you, and I’ve felt the same way. One way to shift that is to expand your focus. Put those binoculars on and zoom out. Start with just one teacher. Build that connection. When you help that teacher solve problems, that frees up time for them to teach, and the word spreads. For example, I once brought in movement-based activities—the drive-thru menus I created—and one teacher said, “Can you write these out?” Before they were even published, she started using them when I wasn’t there. She said, “Every week after you leave, they sit down and do their work—so why wouldn’t I keep doing it?” That teacher talked to others, and suddenly more teachers wanted me in their classrooms. You can start a fire with just a little flame.

How do you handle returning SDC (Special Day Class) students to the general education classroom when they struggled in that environment before? Are schools moving toward co-teaching models?

Yes, I’ve heard about that shift and seen it happening. I think it's essential for the general ed and special ed teachers to collaborate in that model. And honestly, having a therapist join that mix can make a big difference, too. Neurodiversity is more openly acknowledged now than it was years ago, and we know some students without IEPs still need differentiated instruction. That co-teaching approach isn’t a bad plan at all, as long as there's time allocated for collaboration. If the special ed teacher handles adaptations and modifications, the whole process may go more smoothly. But again, time to collaborate is key, which administrators need to support.

Any tips for handling teachers who are resistant to allowing therapists to push into the classroom?

Yes—and I’ve been there. I remember saying to a speech-language pathologist once, “It’s like RTI—about 15–20% just don’t want us in the room, but 80% do.” The reality is that making inroads is tough. Some teachers are stuck, and it’s not your problem—theirs. If push-in is written into the IEP, that’s your backup. Then it’s time to involve the administration. The special ed director must also support the regular ed teacher.

I try to appeal to their needs. I ask, “Have you noticed that this student isn’t able to do what you’re asking?” If they say yes, I offer help. It might sound like I’m trying to comply with their needs, and in a way, I am. Why? Because I want them to want me there. I want them to see that I can make their lives easier with strategies and techniques that support them and their students.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Bowen-Irish, T. (2025). It's never too late to collaborate, school based therapists and educators getting together. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20751. Available at www.speechpathology.com