Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Suicide Awareness, Assessment and Intervention, presented by Nika Ball, MOT, OTR/L, ATP and Angela Moss, PhD, RN, APRN-BC.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Identify suicide definitions, concepts and epidemiology.

- Describe how to differentiate suicide risk factors, comorbidities and warning signs of suicidal behavior.

- Identify appropriate assessment strategies and resources for use in clinical settings.

My name is Angela Moss and this a topic that's near and dear to my heart and to my sister, Nika. I'd like to start with more about us and how we came to be interested in suicide awareness, assessment, and intervention for healthcare professionals. Nika and I are healthcare professionals as noted, but we're also suicide survivors. We lost our younger brother to suicide about five years ago when he was 21. Since his passing, we have become involved in the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and we've become advocates for suicide awareness and intervention for healthcare professionals.

We know that in our educational curriculum for just about any health professional, there are elements of psychology and mental health awareness. But we often don't have curriculum specific for suicide awareness, assessment, and intervention. So that's how we became involved in developing and delivering this content.

Myth or Fact

I like to start with myths or facts because a lot of the issue with suicide awareness is that there's such a stigma around talking about it and as a result, there's a lot of mystery and some myths out there.

Myth #1

“Once a person decides they want to die by suicide, there is nothing anyone can do to stop them.” Do you think that's a myth or a fact? The answer is that it is a myth. Once somebody decides they want to die by suicide doesn't mean that's the inevitable outcome. And because it's not an inevitable outcome, suicide can be prevented. Studies and research have been conducted with people who have survived a suicide attempt. What the research shows is that those individuals say they don't want to die. But, in that moment when they feel suicidal, they have such intense, incredible pain that they feel like ending their life is the only way to make that pain stop. Once they make it through that period of intense pain and they look back on it, they then think, “Oh, I don't want to die.” However, in that moment they couldn't see any other solution.

A lot of the prevention and intervention is to help people and those around them develop tools and to help them get through those intense moments of pain. There are almost always warning signs. Sometimes they're obvious and sometimes they're less so. We'll discuss those in more depth later.

Furthermore, asking a person if they are thinking about suicide does not give them the idea for suicide. It's always important to talk about suicide with people who are suicidal because you'll learn more about their mindset and their intentions. It's not going to give them the idea or validation that they should go ahead and do it. That's related to this prevention intervention type of mindset.

Myth #2

“Suicide only strikes people who are depressed or “weak”. This is certainly a myth, not a fact. In fact, many people who died from suicide are “very strong” or “successful” or however you choose to define strong versus weak. It varies greatly from person to person. But in general, it can affect anybody. The most common cause of suicide is untreated depression. But there are usually several causes, not just one, for suicide. If you think about strong versus weak, anyone can be affected by depression. In fact, it's estimated that one-third of American adults are affected by depression at any given time. So, it can affect anybody, not just people who are “weak.” Additionally, many people die by suicide because a depression is triggered by several negative life experiences and that person does not receive treatment. A series of events might trigger a depression in anyone. Then the depression and the thoughts of suicide go untreated or unnoticed and ultimately results in the person ending their life.

Myth #3

“A person who talks about suicide isn't really going to do anything. They just want attention from other people.” This is a myth, although, some people believe that when a person talks about suicide, they're just trying to get attention.

Let’s think about this. People who die by suicide, and this is backed up by statistics and research, usually talk about it first. Often suicidal people will reach out for help because they don't know what to do when they've lost hope and they're trying to figure out a way out of their misery at the time. Talking about suicide isn't just manipulation or attention-seeking by a person, and certainly assuming so is insensitive and uninformed. If and when someone is talking with you about suicide, whether it's a patient or a patient's family member, you want to always take it seriously and investigate further to determine where they are and what you can do to intervene and help them.

Myth #4

“Young people never think about suicide because they have their whole life ahead of them.” We know that certainly is not true. In fact, suicide is the second leading cause of death for young people ages 10 to 34. The first leading cause of death is accidental injury and/or trauma. Although it's less common, even children under the age of 10 die by suicide. Again, even children and teenagers might be suicidal. They might feel suicidal for a limited period of time and then the suicidal feelings go away. But they can recur over the course of a child's lifetime. It's something that you want to have on your radar, particularly if you work with children.

Definitions

Suicide is defined as the act or instance of taking one's own life voluntarily and intentionally. A suicide attempt is a non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of the behavior. It might not result in injury to one's self. Suicidal ideation (SI) is a common clinical term and is used to describe a person who is thinking about, considering or planning suicide. So, when you're thinking about working with your patients or your patient's family members, you want to document if the person has suicidal ideation or not. Self-directed violence (SDV) is another clinical term that's often used in documentation. It is defined as a range of violent behaviors including acts of fatal and non-fatal suicidal behavior and non-suicidal intentional harm. Lastly, a suicide survivor is a family member or a friend of a person who died by suicide. For example, Nika and I are both suicide survivors.

Stigma

The stigma surrounding suicide is rooted in a fear of social rejection, misunderstanding, ridicule, discrimination, and judgment. Usually, the people who are responsible for perpetuating suicidal stigma engage in behaviors such as distrust, stereotyping, shunning and avoidance toward those affected by suicide. And that really perpetuates the stigma. It's like a feedback loop where there's this fear of social rejection or misunderstanding of what suicide is or how someone comes to have suicidal ideation. Therefore, people don't want to talk about it and they avoid it. There is the stereotype that the person is “weak,” which we know is a myth. But then it just spirals and that's where the stigma comes from. One of the best things to do to debunk the stigma is to talk about it openly and without judgment.

Incidence

Suicide is currently the 10th leading cause of death in the United States. As I mentioned before, it's the second leading cause of death between the ages of 10-34 and it's the fourth leading cause of death between ages 35-54. In 2016, which is the most recent year available for aggregate data, suicide was responsible for 45,000 deaths in the United States with approximately one death every 12 minutes, or 123 suicides per day. Putting that in perspective, in 2016 there were nearly twice as many suicide deaths in the United States as there were homicides. That's any kind of homicide. If you think about what you hear in the news with gunshot violence, for example, there are twice as many suicides as there are of those kinds of death.

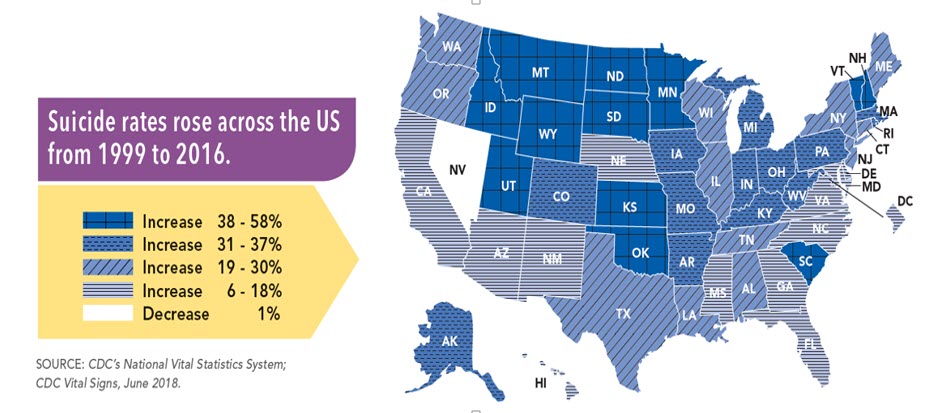

In the past 30 years, we've seen over a 30% increase in suicide rates across the United States. This is also across all racial and ethnic groups, in men and women, in cities and rural areas. It's affecting everyone.

If you look at the map of the United States in figure 1, it looks pretty similar across the whole map. Across the United States, there has been a significant increase in the incidence of suicide that's affecting everybody. Interestingly, according to the CDC, 54% of the people who died by suicide in the past 30 years did not have a known mental health condition. They did not have a diagnosed mental health condition at the time that they died by suicide.

Figure 1. Suicide rates across the US.

Even though suicide affects everyone, it is important to note that there is some variability by race and ethnicity, age and other demographics. It’s small, but in general, the highest rates are among non-Hispanic white populations and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native population. Other groups that are disproportionately impacted by suicide are:

- Veterans or other military personnel

- Workers called the “Triple F” occupational groups (farming or agricultural workers, fishing and forestry)

- Sexual minority youth and the LGBTQ population

Men die by suicide about 3 ½ times more often than women and white males accounted for seven of 10 suicides in 2016. It is highest in middle age and in white men in particular. Suicide rates for white individuals have been climbing faster than those for other racial and ethnic groups. But across the board, suicide truly affects everybody.

Methods

In the United States, firearms is the most common method for suicide among males at about 56%. Among females in the United States, poisoning is the most common and accounts for about $50 billion in fatal injury costs. You can see that suicide has a very large impact on our society.

Risk Factors

We know that suicide affects everybody. You have most likely already encountered it either in your personal life or in your professional life, whether that's working with a patient, a family, or a friend who has contemplated suicide, completed suicide or is a suicide survivor.

Risk factors are characteristics or conditions that increase the chance that a person may try to take their life. It doesn't mean that they're going to; they may never become suicidal. But these are some risk factors: mental health condition, physical health conditions, environmental factors, and historical factors.

Mental Health Conditions

These include depression, anxiety, substance abuse, PTSD, bipolar, schizophrenia, issues with aggression or mood swings or poor social skills or relationships, and conduct disorder. This does not mean if someone has these mental health conditions, they are automatically going to be suicidal. It just puts them at a higher risk of becoming suicidal.

Physical Health Conditions

Personal health risk factors include a chronic physical health condition such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, cancer, arthritis. The list is endless. Chronic pain or a functional disability is a risk factor. Any chronic physical health condition can be a risk factor for suicidal ideation. Traumatic injuries including traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury. And not to be forgotten is post-partum depression. That is a physical health condition that certainly puts someone at a higher risk for suicidal ideation.

Environmental Factors

The first environmental factor is access. If someone has access to lethal items such as firearms, drugs, poisons, etc., then they have a high risk of being able to complete suicide. Prolonged stress such as homelessness or incarceration is also an environmental factor. If the person has a history of being a victim of harassment, bullying, rape, abuse, domestic violence or chronic childhood adversity, that certainly puts them at risk for suicide. Stressful life events such as the death of a loved one, divorce or a relationship instability, financial crisis, or unemployment. Also, lack of social support, isolation or institutionalization and exposure to sensationalized accounts of suicide can put an individual at higher risk for suicidal ideation.

Historical Risk Factors

Historical risk factors include basically anything that wasn’t included in the other three areas. Certainly, if the person has a previous suicide attempt, if there's a family history of suicide or suicidal ideation, a family history of mental illness, particularly bipolar disorder and/or alcoholism, childhood abuse, neglect and trauma, prolonged trauma or stress in the past, poor problem-solving skills and also surviving the loss by suicide of a loved one.

Warning Signs

Those are a lot of risk factors. When you think about the patients that you're working with or your clients, odds are most of them have at least one of the risk factors we just discussed. Once you identify a patient who might have a risk factor, then you really want to look for warning signs. Acknowledging that you might only see your patient or client for a snapshot in time, you might not pick up on all these warning signs. However, it’s important to know what they are and have them on your radar when talking with a client or a family member of your client.

Warning signs can be a change in behavior or sudden occurrence of completely new behaviors. This could be related to a sudden change in life, some type of loss or painful event. Specifically look for changes in the way a person talks, changes in behavior or mood. Obviously, if someone says they were thinking of killing themselves, that is a pretty major warning sign. But, if they talk about feelings of hopelessness, such as, “I just don't really have any reason to live” or “I'm a burden to others” or talk about feeling “trapped” can be a warning sign (e.g., trapped in a job, trapped financially, trapped in a relationship). If that type of talk is persistent, it can be a warning sign for someone at risk for suicidal ideation. Talking about unbearable pain is another warning sign. Comments like, “I just can't take this anymore.

Behavior Warning Signs

Behavior warning signs would be increased use of drugs or alcohol. That might suggest they're trying to find an outlet from the pain that they are experiencing. Also, looking for or researching a way to end their life. There have been studies where teenagers who either attempted suicide or completed suicide, parents went back and checked their children’s web browser and they found searches for ways to end their life.

Withdrawing from activities is a behavior warning sign that should be on your radar. Isolation from family and friends is another one. Sleeping too much or too little; any change in their normal sleep pattern that seems to be extreme in either direction can be a warning sign. Visiting or calling people to say goodbye is certainly a warning sign. Giving away prized possessions, showing aggression and fatigue are all behavior warning signs.