Introduction and Overview

Thank you so much for your participation today as we discuss the role of the SLP in palliative care. In my experience, palliative care is a concept that many people are unfamiliar with and is often misunderstood. Hopefully, after this course, you will understand how palliative care is defined, as well as the SLP's role across different healthcare settings, including acute care, skilled nursing, long-term care, and outpatient/home health care.

To provide some background, I spent the first year of my career in acute rehab in the brain injury unit. Back then, palliative care was not a topic that was commonly discussed. After that, I spent about 16 years in an acute care environment. Over that 16-year period, I started to see palliative care come to the forefront, and what we as SLPs can do on the palliative care team. From there I moved into post-acute care. I've seen palliative care applied in all settings. I truly believe SLPs have a lot to contribute to the field of palliative care, no matter what setting we are in.

The course agenda includes:

- Introduction and Definition and description of Palliative Care

- Palliative Care vs. Hospice Care

- SLP role in palliative care in acute care

- SLP role in skilled nursing rehab, long-term care, and OP/Home

- Advance directives, DNR’s and those pesky waivers

- Rehab therapy defined- skilled to restore function and skilled to maintain function

- Conclusion and questions

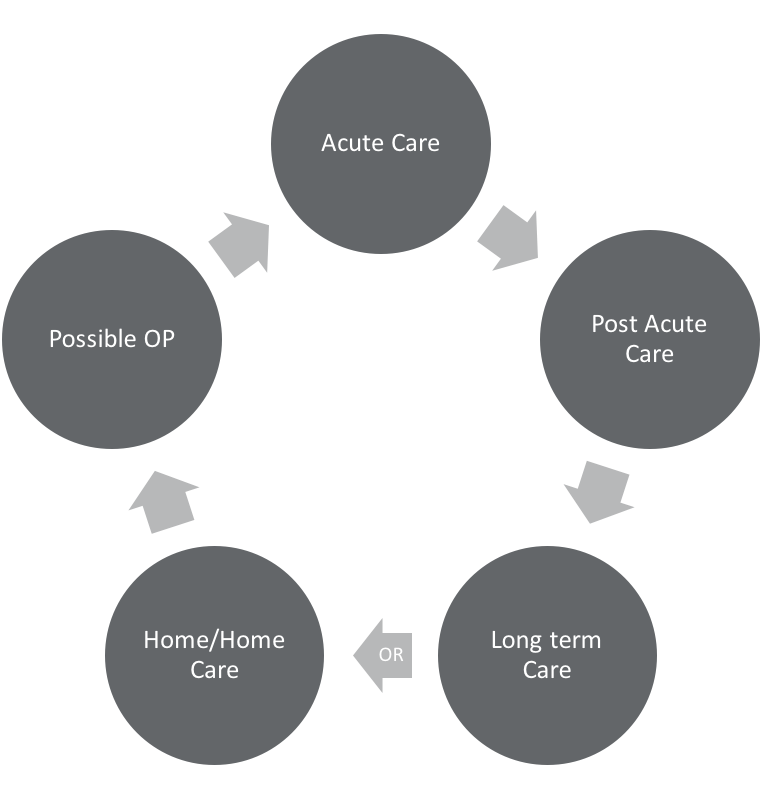

The Healthcare Cycle

Figure 1 shows a diagram of the healthcare cycle. We may have a patient that starts in acute care and then transitions to post-acute care, eventually going to long-term care or home care, possibly going straight home, and maybe needing outpatient therapy after that. However, the patient's journey doesn't always follow a clean cycle. Sometimes they go to acute care, then they go to post-acute care, and then they have to go back to acute care, and then they go right to their home. Perhaps they go to outpatient, but in the middle of outpatient, they go into an acute care environment again. We overlap, we weave. It's never a clean, neat cycle. We encounter patients at all levels.

Figure 1. The healthcare cycle.

Hospice vs. Palliative Care

Let's distinguish between hospice and palliative care, which is a source of confusion for a lot of people. Hospice and palliative care both offer compassionate care to patients with life-limiting illnesses. Palliative care is always a component of hospice care. If a patient is receiving hospice care, then palliative care is going to be a component of that. However, a patient can receive palliative care and not be receiving hospice care. Palliative care can be considered sort of an umbrella, where hospice care sometimes fits in and sometimes it doesn't. The main point to remember is that palliative care is focused on relieving symptoms that are associated with the patient's condition, but that patient may be receiving active treatment for the condition. Palliative care can occur along with the active treatment of a curative approach. Hospice care is reserved for terminally ill patients when treatment is no longer curative, assuming that the disease takes its normal course. Generally, there's a six-month time frame for a terminal illness during which time the disease is expected to take its course. Palliative care can be rendered while the patient is continuing active treatment through different phases of their life-threatening condition.

Palliative Care

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as "an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with a life-threatening illness, through prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual."

I like this description of palliative care from Goldstein and Fischberg (2008): "Comprehensive care and management of the physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual needs of patients and their families with chronic, serious, or life-threatening illness." I want to focus for a minute on the component of patients and families. Many times we think about working with the patient and treating the patient. In palliative care, we are including the patient and their family as a whole. We're looking at them all together to determine how we can pull everybody together for the best quality care and care plan. We should be doing that anyway when we're working with patients, but it's specifically a focus for palliative care.

The other key component, according to Goldstein and Fischberg, is that palliative care allows the potentially curative treatment to continue. It focuses on reducing symptoms that may be associated with the disease itself or which may come from the curative treatments themselves. Let's think about a patient with head and neck cancer. What are we working on? We're working on reducing symptoms from the radiation. The radiation is the curative treatment, and it's causing a lot of symptoms that we're trying to alleviate. We're working on trying to lessen the patient's symptoms, not only from the etiology of what's happening but from the treatment that the patient has chosen to undergo. The focus is on quality of life, enhancing the patient's functional ability, and facilitating decision making.

The palliative care goals are to address for both the patient and the caregiver emotional/spiritual concerns, cultural beliefs, preferences, and their own wants and needs. We're involved in coordinating the care, providing the input and the feedback to the whole team, and improving quality of life. It's an important job.

Palliative care has many benefits, including improving quality of life, reducing pain, and shortening hospital stays. For those of you who work in an acute care environment, you know that hospital stay length is critical for a couple of reasons. First, a reduced hospital stay is a financial benefit to the hospital. More importantly, studies have shown that reduced hospital stay reduces the risk of infection. We want to get those patients out as quickly as possible so that they don't become sicker. Another benefit of palliative care involvement is a reduction of burden of care and emotional distress for the caregiver. Most importantly, the patient feels in control. It can be extremely empowering for a patient when they know that they're in control of their own health. As a result of that, we see improved mood and reduced depression in patients who otherwise may have symptoms of depression due to their illness.

Role of the SLP in Palliative Care

The role of SLP is to provide consultation to patients, families, and members of the team in the areas of communication, cognition, and swallowing function. We assist in optimizing function. We promote positive interactions with feeding. We develop and provide ongoing strategies for communication skills. Remember, we are the communication experts (Pollens, 2004).

Who's on this palliative care team? If done correctly, it involves a lot of people. We have physicians, nurses, and social workers. We have chaplains, counselors, dietitians, pharmacists, PT, OT, music/art therapy, and speech pathologists. Sometimes we are inadvertently left off of this team. One thing that I want people to take away from today's presentation is if you're not already part of a palliative care team, you need to advocate to become a part of it. SLPs are an integral component and we provide good benefit to palliative care patients.

SLP Role in Acute Care

In general, over the past decade, palliative care has been one of the fastest-growing trends in health care. In fact, the number of palliative care teams within US hospitals with 50 beds or more have increased by 164% since 2001. Clearly, it's a growing and necessary trend that is not going away (Center to Advance Palliative Care, January 2017).

We see patients in acute care throughout all stages of an illness. We see them at the onset. We see them in the middle or exacerbation of an illness. Many times, we've seen them toward the end. We've witnessed death. I'll never forget the first time I worked with a patient in a palliative care approach. We were working on improving quality of life. This patient had severe dysphasia. I remember the first time I witnessed the progression of the disease to the point of terminal illness and seeing the patient to the end. It was one of the most difficult points of my career, but it was also one of the most rewarding to know that I was working with that patient and family, and I could watch them have a peaceful end. It was kind of a turning point for me to know that I played a part of that. It was a humbling experience for me.

The SLP serves many purposes when working with acute care patients. We will analyze the following areas of involvement:

- Communication needs

- Language and motor speech needs

- Communication aids and alternative communication (making sure that the patient has a means of communicating their wants and needs, opinions, and guiding their own care).

- Dysphagia

- Evaluations

- Recommendations for dysphagia management and having a unified message

- Feeding tube

- The DNR dilemma

The patient populations that we see in acute care vary widely and include those with:

- Chronic Respiratory failures

- CVA

- Head and Neck Cancer

- Neurological impairments/disease (Parkinson’s and others)

- Heart Failure

- Dementia

Communication

With regard to communication and cognition in acute care, the SLP works a lot with the patient's health literacy. Health literacy is defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services that are needed to make appropriate health decisions. The focus on health literacy has mainly been on patients who either had low literacy, illiteracy, or second-language barriers. But what about aphasia? What about cognitive impairments? For patients with aphasia or a cognitive impairment or some sort of language breakdown, we need to make sure that they have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information. How are they understanding their health? What's going to be guiding them on their health decisions? Are they able to process all of the information about their medical condition? Are they able to verbally express what their wishes are, and their wishes in the realm of palliative care? Our role is to assist with that communication, providing appropriate communication aids and the compensatory strategies that are needed. We also work with patients, families, and healthcare teams by being an advocate for the patient to make sure that the patient is adequately being heard, understood, and that they are understanding what is going on around them.

If an SLP is working in the ICU or CCU, the patient may not have aphasia or a cognitive impairment, but they may be unable to communicate verbally because of vents or something that would inhibit them from having effective verbal communication. In those cases, we can provide simple communication aids (e.g., communication boards) so that we know the patient is adequately able to communicate their wants, their needs, their wishes, and their goals for palliative care.

Dysphagia

Sometimes when SLPs receive dysphasia consultations, in my experience, it seems that there is a "revolving door" of consults. What do I mean by that? I'll give you a scenario. A patient named Mr. Jones comes in and we are consulted. The patient has dysphagia. We recommend NPO for this patient. He is not swallowing correctly. What I have seen occur is that we recommend an NPO and we see Mr. Jones for a little while, and then we discharge with no further involvement. Then what happens? He wakes up a little bit, and we get re-consulted. We come in and there's a little bit of progress, and then we discharge. And then we get re-consulted. What ends up happening is that we never take into account the patient goals or family goals. We never discuss it with the medical team. We might discuss our recommendations, but we need to look at the situation as a team to determine how we can come together for this patient and address his key needs and goals for dysphagia treatment. Do we need to be getting re-consulted for instrumental studies when perhaps the patient doesn't want that? Maybe they don't want any more intervention. Maybe they want to modify their diet, maybe they don't. Are we asking the patient and taking into account what they truly want? I believe that if we just took a step back and worked with the team, we'd have an end to this "revolving door" of consults.

When working with a patient and the family, we first have to find out their goals. We also need to take into consideration the goals of the nurses, physicians, and other team members. If a nurse tells me, "I just need to know how to give pills," as the SLP, that's not our goal. Maybe they are looking to us for guidance. Again, we need to start advocating for our profession. If we are able to assist in the overall management of this patient who is receiving palliative care, medication management is a key component. It may be that the patient's goal is to receive medication safely. If that's the nurse's goal, we need to work with them. What is the physician's goal? Why is the physician calling us in? We need to make sure that we ask the physician for the rationale behind ordering the consult.

We need to have instrumental assessments to know what we're treating. We don't have x-ray vision. Instrumental assessments are our best bet to understanding what's going on, and where the breakdown is so that we know how to adequately treat. But when is that not appropriate? When is the patient allowed to say, "I don't want any more swallow studies. I just need to know how to be comfortable."

As SLPs, do we ever go beyond being diagnosticians? Yes, we do that. We don't end at the diagnostician part. Sometimes, that's where we say, "Okay, we've diagnosed, we've provided our recommendations, and that's it." In the acute care environment, we tend not to have the time to come up with these huge treatment plans. But again, managing the comfort level is a key part. SLPs are a valuable key team member, and we need to make sure that we are advocating for our profession.

As SLPs, we also need to make sure that we have a unified message on the benefits and dangers of changing recommendations. If we have a large team of SLPs in our acute care departments, we need to make sure we are all on the same page. For example, on day one, SLP A recommends puree and honey. The next day, SLP B goes in and changes the recommendation to NPO. On day three, SLP C comes in and changes it back to puree and honey. Also, we need to look at a safer diet for our palliative care patients and make sure everyone on the team is informed of what that diet is. Anyone participating in this course now is taking a step toward learning more about palliative care. However, you need to go back to your team and relay what you have learned and how you will go forward. We all need to get there together. If one of us is working towards a palliative care approach but the others aren't, that does not benefit the patient.