Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Radiation Safety and the SLP, presented by Tom Giza, MS, CCC-SLP.

It is recommended that you download the course handout to supplement this text format.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the basic principles of radiation safety and how they apply during VFSS.

- Identify the appropriate use and positioning of personal protective equipment (PPE) for SLPs and patients during fluoroscopy.

- Explain strategies for timing and positioning that minimize radiation exposure without compromising diagnostic outcomes.

- Discuss how to communicate effectively with radiology personnel to coordinate safe and efficient VFSS procedures.

Introduction/Presenter Bio

With nearly 14 years of experience, including 12 years in acute care hospital settings, I've developed a deep expertise as a speech-language pathologist. My career began in a skilled nursing facility before I found my passion for acute care, where I've spent over eight years specializing in instrumental swallowing evaluations. I perform both videofluoroscopic swallow studies and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluations of swallowing (FEES) with similar frequency.

My professional interests extend to neurogenic disorders and the specialized care of patients on ECMO and those with cardiac conditions. I am currently developing a webinar to share best practices for SLPs in this area. Beyond my clinical work, I am a PhD candidate researching how we interpret residue during swallow studies. This research complements my passion for education, as I continually explore effective methods to teach and mentor both students and colleagues.

Purpose & Focus

Mastering radiation safety is crucial for both clinicians and patients during swallow studies. This presentation will be your guide, starting with a breakdown of the fluoroscopy machine and the videofluoroscopic suite to understand how each component influences radiation exposure. We'll then delve into practical, evidence-based strategies to minimize risk, including optimal positioning, leveraging protective equipment, and navigating radiation scatter. Finally, we will define the essential role and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists in a fluoroscopy environment and explore how we can collectively improve safety standards in our field.

Radiation and X-Rays

Let's first talk about radiation and X-rays.

What is Radiation?

Radiation is a form of energy that moves through space as particles or waves. In this context, we will focus on electromagnetic (EM) waves, which have different frequencies, wavelengths, and energy levels depending on their source. Think of it like a spectrum of energy, from radio waves to X-rays and gamma rays. The higher the frequency, the more energy the waves transmit. Our bodies react differently to this energy depending on the part exposed, such as the eyes, hands, head, feet, or thyroid. We'll explore how each of these body parts responds to various types of radiation and at what point it becomes a health risk. We are already familiar with how our bodies react to simpler forms of radiation like heat, light (such as UV rays), and even sound, but it's crucial to understand how more complex EM waves, like those used in medical imaging, interact with our tissues.

Wavelengths and Frequencies

Let's delve into the relationship between wavelengths and frequencies in radiation, starting with lower-frequency waves and moving to those with higher frequencies.

Lower-frequency waves have a longer space between their peaks, which means they move more slowly and are less harmful. These are known as non-ionizing waves because they are not powerful enough to detach electrons from atoms and break chemical bonds. Examples of these waves include radio and sound waves, which don't cause ionizing damage.

In contrast, high-frequency waves have a shorter space between wavelengths. They transmit more energy and are considered ionizing waves because they are strong enough to break apart chemical bonds. A common example is ultraviolet (UV) rays. When you get a sunburn from not wearing sunscreen, you are visualizing the result of these waves breaking chemical bonds and causing tissue damage.

Video Fluoroscopy

Let's now go through the parts of video fluoroscopy.

X-Rays

This all begins with the creation of X-rays, and understanding which part of the machine actually produces them is key. This happens within the X-ray tube, which we'll examine in more detail shortly. When you're in a fluoroscopy suite, you'll notice a part of the machine marked with negative and positive signs representing the cathode and anode. This is where electrons flow from the negative (cathode) to the positive (anode) portion, driven by the principle that opposites attract. The electrons are generated from an electrical input to the machine, and X-rays are created as they travel through the tube from the cathode to the anode. This occurs specifically when electrons are scattered on a target within the X-ray tube.

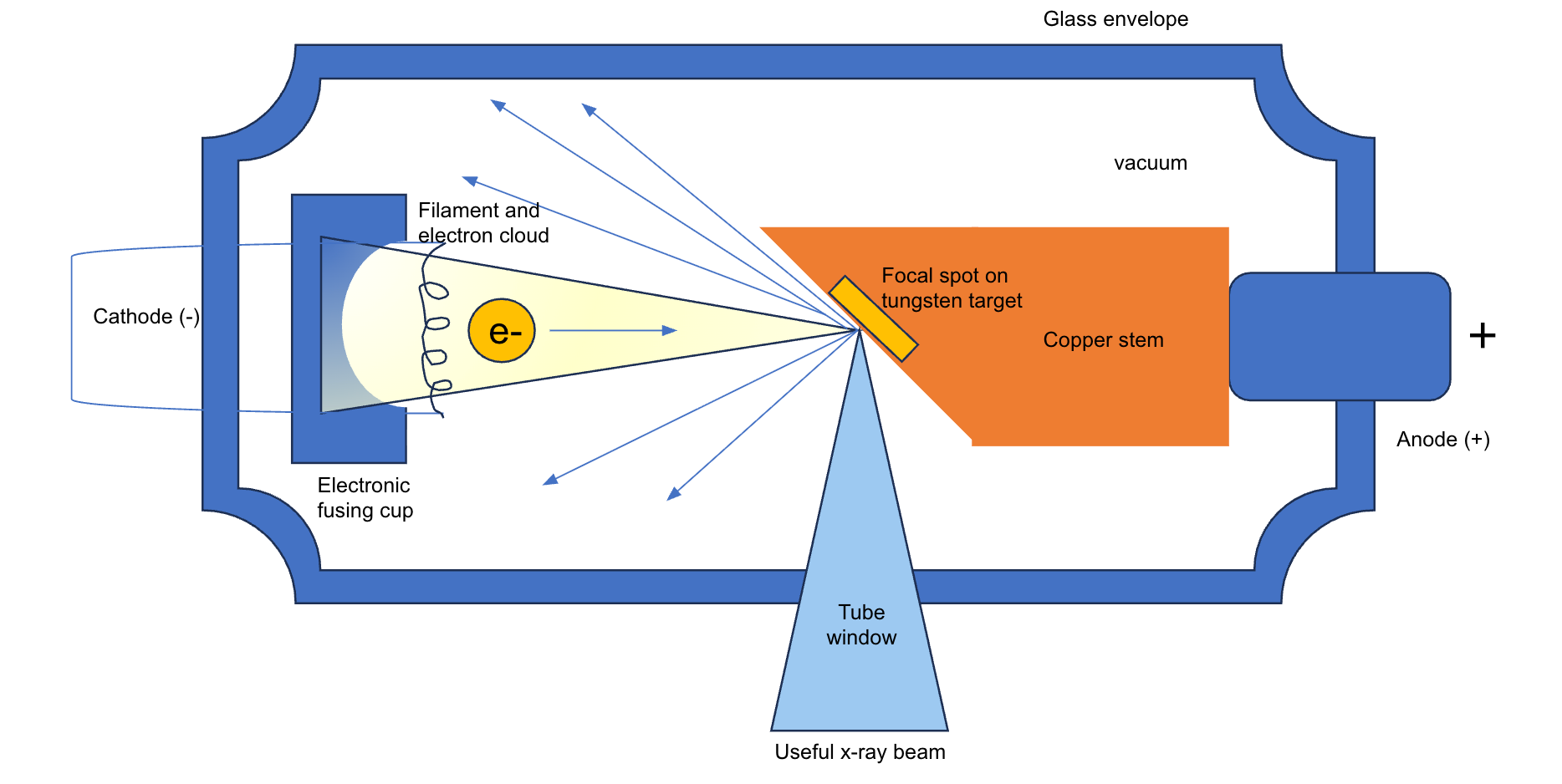

Figure 1 shows a picture that I created using different shapes.

Figure 1. X-ray tube. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

On the left, we have the cathode, which is connected by a cord. This is where the electric current begins. There's an electric focusing cup on the left side, and you'll notice its concave shape. As electrons are created through this current, they form a cloud. The focusing cup, due to its shape, concentrates these electrons towards a specific part of the anode on the right side of the picture—a spot called the tungsten target.

At this point, these electrons are focused. They are multiplied on the left, forming a cloud, and then the concave electronic focusing cup directs them to a specific target where they will scatter. This entire process takes place within a vacuum, a highly controlled environment. This is essential because, without it, X-rays would scatter uncontrollably throughout the room instead of penetrating the precise area of the patient's body we need to visualize.

This is all encased within a glass envelope. There's also an opening called a tube window. After some X-rays scatter, the ones necessary to create the X-ray beam scatter through this open tube window. These electrons move to the next point of the videofluoroscopic machine to produce the X-rays we need to visualize a patient's swallowing.

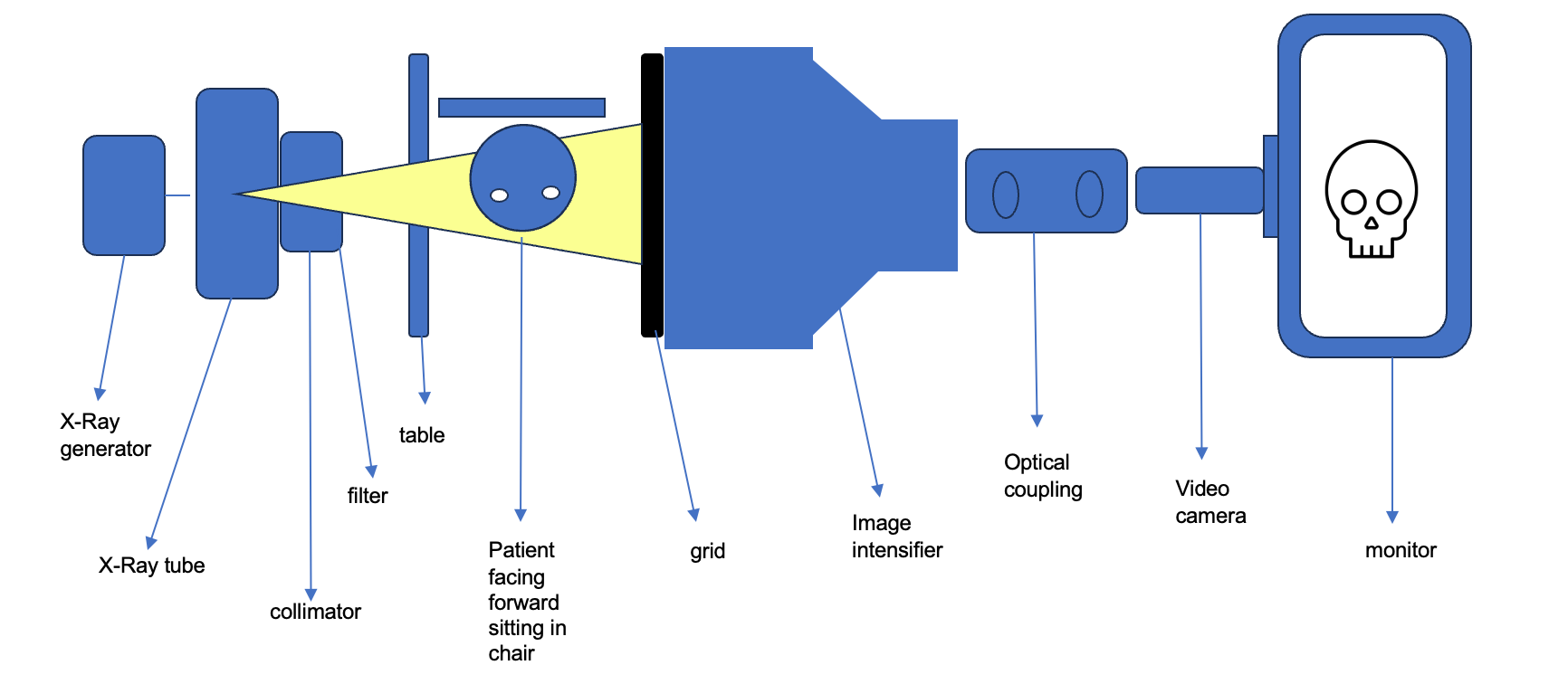

I drew Figure 2. This is a "bird's eye view" of the client.

Figure 2. Bird's eye view of the X-ray tube. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

In this setup, I visualize the patient facing forward in the middle. On the left, an electrical input connects to the X-ray generator, which supplies the electromagnetic waves within the X-ray tube we previously discussed. Once the X-rays are created in the tube, they move through the collimator. I think of the collimator as a filter that organizes the X-rays into straight lines. This is crucial for obtaining complete images and ensuring the X-rays are directed accurately through the patient. The collimator also enhances image quality and reduces radiation exposure by coordinating and filtering the X-rays.

Next, the X-rays pass through a filter. This filter produces a cleaner image by absorbing low-frequency X-rays that are prone to scatter and higher-frequency X-rays that can cause tissue damage. By using the collimator and filter, I am actively protecting the patient.

After moving through the patient, the X-rays hit the grid. The grid further reduces scatter and improves image quality by absorbing X-rays that have passed through the patient. This also helps minimize scatter around the room.

The remaining X-rays then enter the image intensifier. The image intensifier amplifies faint light into visible light images, allowing me actually to see the picture of the patient's anatomy.

Finally, the image is transferred to the monitor through the optical coupling portion of the machine. The optical coupling uses different lenses and fibers to take the information from the X-rays, after they have gone through all the previous stages. It converts it into an image I see during a swallow study.

Parts of the Fluoro Machine

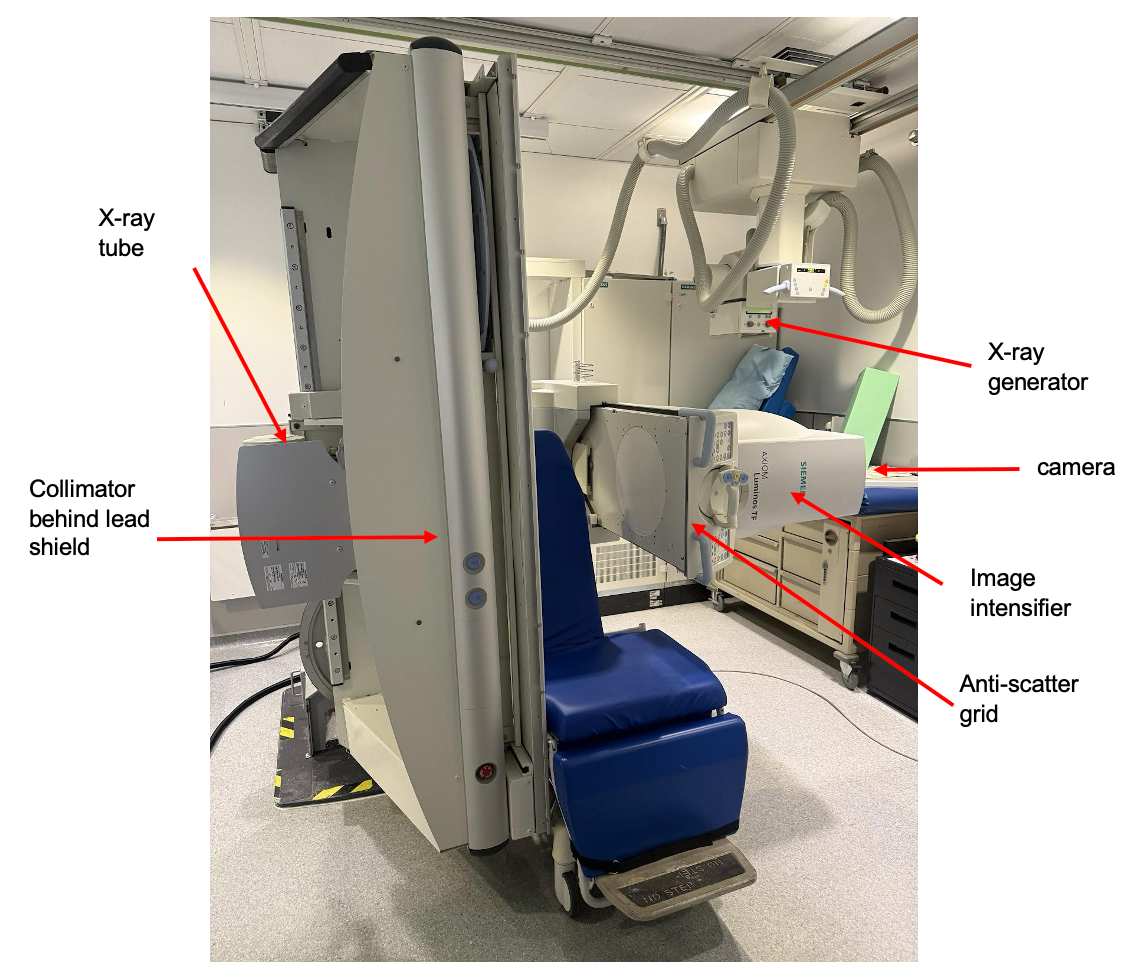

An image of the fluoro machine is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. A fluoroscopy machine.

If I were to look at the other side of the X-ray tube, I would see a negative sign at the top and a positive sign at the bottom. This is where the X-rays are produced and generated. The electrical input that creates this flow originates at the X-ray generator in the back and moves to the left side. This is important because, as we'll discuss later, the origin point of the X-rays significantly influences where I stand and how much radiation I am exposed to. It's crucial to be familiar with whether the X-rays are coming from the left or right side of the machine, as there are many different setups and types of fluoroscopy machines. At my hospital, I adjust my standing position within the fluoroscopy suite based on the specific anatomy and parts of the machine being used.

Looking at the image, I see the collimator positioned behind a lead shield. There's also what looks like a bed, currently in a vertical position, with a portable chair. During pediatric swallow studies, I remove the chair and place the table horizontally to lay a baby in a side-lying position for the study. This is because we feed infants, often on the left side, while lying down. On the right side, I see the anti-scatter grid, the image intensifier, and the camera. The radiologist typically stands on the right side of this picture.

As I mentioned, the beam collimator uses shutters to help focus the beam and reduce spillover and scatter. The beam filter then further reduces the radiation dosage that contacts our skin by removing harmful high-frequency rays and absorbing the lower-frequency waves that are more likely to scatter around the room.

I also talked briefly about the table, which is currently in the vertical position in this photo, and the anti-scatter grid on the right side. The anti-scatter grid helps improve image contrast and reduces scattered X-rays that could contact the image receptor on the opposite side. The image intensifier is responsible for converting the X-rays into light for imaging.

In this setup, I would typically have a monitor hanging from the ceiling outside of the immediate picture. It's on a track and adjustable, allowing me to move it to the best possible position for viewing during the swallow study.

Participation Time

Figure 4. A fluoroscopy machine.

In this image, where would you stand while conducting a videofluoroscopic swallow study? Would you stand at point A, next to the radiologist; point B, right in front of the patient; or point C, to the left of the patient? We'll revisit this image later in the presentation to see if your answers change. Now, let's move on and discuss radiation exposure and its effects.

Effects of Radiation Exposure

Now, let's talk briefly about radiation exposure and its effects.

Effects and Risks

The effects of radiation can be acute, meaning you might see them immediately, like a sunburn, or within an hour or two. However, there are also delayed effects. These delayed effects can include conditions like leukemia, cancer, cataracts, and even genetic changes. This is because we know that these X-rays can alter the charge of different ions, leading to tissue damage and DNA damage.

It's important to understand that there's no guaranteed occurrence of these effects because so many factors contribute to conditions like cancer, putting some individuals at higher risk and others at lower risk. However, it is clear that a higher radiation dose increases these risks – the risk of developing leukemia, cataracts, or genetic changes. While immediate exposure effects leading to death are associated with events like nuclear incidents, I've already touched upon the more common tissue damage seen with things like sunburn.

Radiation Exposure Variables

The type of radiation significantly impacts how our tissue can be damaged. As I mentioned, lower frequency waves like sound and radio are less likely to cause harm, while higher frequency waves, such as UV and X-rays, pose a greater risk of damage. The dosage, or the amount of radiation passing through, also plays a crucial role; a higher amount is more likely to damage tissue than a lower dose. Furthermore, the rate at which radiation is delivered matters. During swallow studies, I operate at 30 frames per second to ensure I can observe the complete swallow and avoid missing any instances of penetration or aspiration, which might occur at a lower rate, like 15 frames per second. While necessary for a thorough examination, this higher rate increases the potential for tissue damage.

Organ Sensitivity to Radiation

Sensitivity | Cell | Tissue or organ |

High | Lymphocytes Spermatogonia Erythroblasts Intestinal crypt | Lymphoid tissue Gonads Bone marrow Intestines |

Medium | Endothelial Osteoblasts Spermatids Fibroblasts | Skin Growing bone Connective tissue Kidney, Liver Thyroid |

Low | Muscle Nerve | Muscle Brain Spinal |

The recipient's age also significantly affects how radiation affects us. Certain body parts are more susceptible, including lymph nodes, genitals, gonads, bone marrow, and intestines. These areas contain corresponding cells that are more sensitive to radiation. This sensitivity is why we use lead protection in specific areas. For example, we all wear thyroid shields during swallow studies, and how the lead is positioned on our bodies helps protect other areas like our genitals and intestines.

Other areas with median sensitivity to radiation include skin, growing bone (making younger populations more susceptible), connective tissue, kidneys, liver, and the thyroid. Body parts with low organ sensitivity are muscle and nerve cells in our muscles, brain, and spine.

Age and Radiation Exposure

Let's discuss the impact of age on radiation exposure. It may not be surprising, but children are more susceptible to developing cancer later in life if they are exposed to radiation while their bodies are developing and growing. Their cells rapidly divide at a younger age, and their organs are still forming. If these developing organs are exposed to significant radiation, it can cause the ionizing damage we discussed earlier. This can lead to changes in their DNA and cell structures, potentially causing cancer cells to develop.

However, being older does not eliminate the risk of developing cancer from radiation exposure. The relationship between age and reduced cancer risk with radiation exposure is not linear. As we age, our cells undergo deterioration, and there's an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants. Additionally, older cells have an impaired DNA damage response, meaning they don't repair themselves as effectively as younger cells. We also face an increased risk of inflammation as we age, which can further contribute to the effects of radiation.

Radiation Limits

While each state may have varying radiation limits, federal regulations, specifically Title 10, Part 20, of the Code of Federal Regulations (10 CFR Part 20), establish dose limits for radiation workers. The annual total effective dose equivalent (TEDE) for the whole body is set at 5,000 mrem (5 rem). I will also discuss how different body parts have different dose limitations. However, the 5,000 mrem (5 rem) restriction for the whole body is what I found to be most consistently applied.

According to OSHA

According to OSHA, "No employer shall possess, use, or transfer sources of ionizing radiation in such a manner as to cause any individual in a restricted area to receive, in any period of one calendar quarter from sources in the employer's possession and control, a dose in excess of the following limits." I have converted these measurements to reflect annual limits. OSHA's limits align with federal regulations, stating that the annual total effective dose equivalent for the whole body should not exceed five rem or 5,000 mrem.

Body part | Rem/mrem |

Whole body Head Trunk Active blood forming organs Lens of eye Gonads | 1.25 rem/1,250 mrem per quarter = 5 rem/5,000 mrem per year |

Hands Forearms Feet Ankles | 18.75 rem/18,750 mrem per quarter = 75 rem/75,000 mrem per year |

Skin of the whole body | 7.5 rem/7,500 mrem per quarter = 30 rem/30,000 mrem per year |

Federal regulations specify different restrictions for various body parts regarding radiation limits. The annual limit for the whole body is 5,000 millirem (5 rem). More sensitive areas, such as the head, trunk, blood-forming organs, the lens of the eye (due to susceptibility to cataracts with high exposure), and genitals, are included within this 5,000 millirem limit.

However, certain body parts are allowed to receive more radiation exposure. These include the hands, forearms, feet, ankles, and skin. This makes sense for areas like the skin, as we are naturally exposed to radiation from the sun and Earth when outdoors. Similarly, I expose my hands and forearms during swallow studies as I feed the patient. Compared to the five rem per year for more sensitive body parts, our hands, forearms, feet, and ankles have a limit of 75 rem per year. Our skin also has a higher annual limit of 30 rem or 30,000 millirem.

What Does 5,000 mrem Look Like?

I have listed a few procedures and their millirem equivalence.

Procedure | mrem |

Whole body CT | 1,000 |

Upper GI X-Ray | 600 |

Radon exposure from home (1 year) | 228 |

Head CT | 200 |

High elevation causing radiation exposure | 80 |

Mammogram | 42 |

Cosmic radiation | 30 |

VFSS | 20 |

Chest X-Ray | 10 |

When we look at radiation exposure, a whole-body CT scan is approximately 1,000 millirem. Considering the annual limit of 5,000 millirem, I could undergo a maximum of five such scans annually. Similarly, an upper GI X-ray is about 600 millirem, and the average annual radiation exposure is around 228. A head CT is 200, a mammogram is 42, and cosmic radiation is 30.

A videofluoroscopic swallow study is estimated at 20 millirem, while a chest X-ray is 10. However, this 20 millirem figure for a video swallow can be highly variable. It largely depends on the therapist conducting the study and the complexity of the swallow itself. For simpler cases, I might use less fluoroscopy, thus radiating the patient less. Conversely, if a patient takes longer to chew and swallow, or requires significant cueing, the study could expose them to more than 20 millirem.

It's important to note the difference: a chest X-ray is a single image or frame, whereas a video swallow involves 30 frames per second. This means the 20 millirem figure can fluctuate significantly. Suppose I'm performing a study at 30 frames per second and radiating a patient for two to five minutes (at my workplace, they aim for under two minutes, and the machine typically beeps after five minutes of radiation). In that case, the actual exposure can certainly exceed 20 millirem, in my opinion.

Radiation Safety During Pregnancy

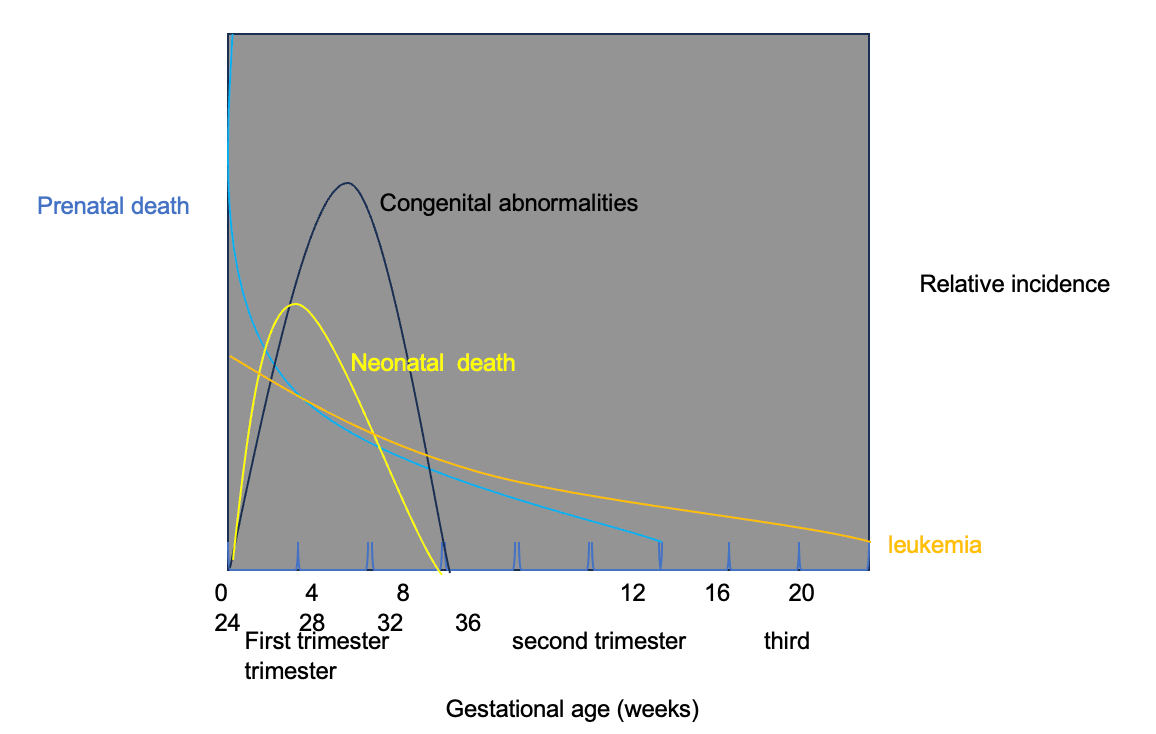

Let's talk about radiation safety during pregnancy. So the embryo is most vulnerable to radiation during the first trimester. I also made a chart or a picture in the next slide, highlighting how embryos are most sensitive during this first trimester.

The American Speech Hearing Association (ASHA) recommends using standard precautions to help reduce exposure below the dose limit recommendation. So that would mean wearing an apron that has the most lead, positioning the patient in a way where you can still feed them about exposing yourself, being really efficient during the exam, maybe practicing with the patient some strategies beforehand before you start the swallow study, or telling the radiologist to turn on the radiation at a specific time versus having them radiate from the very beginning. We'll go through more of the compensatory strategies and caveats you can use to help reduce this radiation. They also recommend monitoring your radiation dosimetry badge more frequently. They recommend wearing an additional dosimetry badge underneath the lead at your waist to have one right on, right on your clothing, and then wearing lead. I've also heard of some places that would recommend double leading. One on the front, one on the back. And we'll go over the parts of the lead where radiation can enter. They also recommend declaring your pregnancy to the radiation safety officer, who can provide extra protection and training to help reduce the radiation risk and exposure. The maximum dose equivalent to the embryo and fetus during pregnancy cannot exceed 0.5 rem. So, compared to our five rem, it would be 0.5 that you should expose the embryo or the fetus during the entire pregnancy.

Figure 5 shows a graph I created.

Figure 5. Radiation safety during pregnancy. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

When I look at the weeks at the bottom of the chart, I see that during the first four weeks, there's a high risk of prenatal death due to radiation exposure, and the risk of neonatal death peaks around four weeks. The risk of congenital abnormalities also peaks within the first trimester. So, I see a pattern here where the first trimester is what matters most to protect an unborn child. I've also seen some therapists who avoid doing fluoroscopy during the first trimester. It's really up to you, your choice, and communicating that to your employer. The risk of leukemia is also higher at the beginning of the first trimester. It tapers down by the third trimester but doesn't completely decrease. These are all relative incidences and rates of incidence. When researching, I haven't found any official limit on whether I can do a pediatric swallow study or use radiation. I've given this presentation several times and always try to check for updates or new information.

Radiation Exposure in Pediatric VFSS

I haven’t found an official universal limit for pediatric swallow studies. Some countries recommend keeping annual exposure under 100 mGy, and those recommendations are typically framed per year. A 2019 study by Co and colleagues reviewed 89 children who underwent swallow studies and found the average radiation exposure per study was approximately 29 mGy. Applying that average to the more conservative country-level guidance roughly translates to not exceeding about three swallow studies in a year. We also know children are more susceptible to radiation-related harm because they are developing organs and actively dividing cells. Most sources emphasize the ALARA principle—as low as reasonably achievable. These are not elective studies; children undergo swallow studies because significant clinical questions need answers. The results can meaningfully impact their care plan, length of hospital stay, and overall medical trajectory. Given that, a careful cost–benefit analysis is essential. I discuss the indication, timing, and frequency with the care team and the radiologist: How much radiation is truly necessary, and how often, to safely guide management? In my current work with adults, for example, we try not to repeat a swallow study more than once a week. We ask how much clinically significant change is likely within a few days. While rapid changes can happen, spacing studies help us capture a more stable and representative picture when possible. In practice, my approach is to individualize decisions: confirm that each study will likely change management, optimize technique and exposure to minimize dose, and coordinate with the team to avoid unnecessary repeats—especially in pediatrics—while not delaying care when timely information is critical.

What Can We Do?

What Is Our Role According to ASHA?

According to ASHA, my role is to make appropriate selections and referral recommendations for who should participate in an instrumental swallow study. I look for patients who follow directions and demonstrate relatively consistent and timely swallowing so that the study will yield valid, actionable information. Given the radiation exposure, if a patient requires significant “warm-up” to achieve functional swallowing, I ask whether VFSS is the best choice at that moment. In some cases, FEES may be more appropriate.

Timing and endurance are also critical considerations. If a patient has limited endurance, I ask whether a single study will capture their full swallow trajectory. We may spend about 30 minutes in the fluoro suite, but does that window reflect what happens when the patient fatigues or decompensates? Sometimes aspiration emerges specifically under fatigue. To address this, I plan the session to sample at clinically relevant time points and loads. I also coordinate with the team to decide whether FEES, bedside observation across meals, or repeat assessment at a different time of day would better capture those fatigue-related changes.

Even when using radiation, I remain mindful of frequency. I avoid repeating two swallow studies in the same week unless there are clear, drastic clinical changes that are likely to alter management. I plan the VFSS, practice likely maneuvers and compensatory strategies with the patient beforehand, and complete a thorough oral mech exam to identify suspected oropharyngeal weaknesses. For example, if I anticipate a benefit from a left head turn, I will rehearse that with the patient. Hence, the exam proceeds smoothly with fewer retakes and less unnecessary exposure. I also work with the radiologist and technologist to ensure optimal positioning, appropriate shielding, efficient sequencing, and tight time management to minimize exposure.

Regarding personal protective equipment, I’m meticulous. In the photo I share during in-services, I wear lead with a thyroid guard and an apron. There are one-piece and two-piece aprons. I prefer the one-piece because it provides seamless coverage. Early in my career, I learned that a two-piece can shift—during my first swallow study, the bottom half kept slipping, which was distracting and less protective. Fit matters: I make sure the apron is snug and tucked up into my axilla so that breast tissue is fully covered. My favorite setup includes a thyroid guard that sits high under my chin with no gap between the guard and apron; mixing and matching pieces can sometimes create gaps, so I check that before starting. When I onboard students, I have them try on several aprons and guards in advance so they can choose a comfortable, protective set—there’s nothing more stressful than hunting for the right fit right before meeting a patient.

Eye protection is also essential. I label our leaded goggles “Property of SLP” because, at one point, the radiologists wanted to claim them—our department purchased them for our use. These goggles protect the eyes' lenses from radiation and should be worn during the study. They can fog with a mask, but adjusting the mask higher on the bridge of the nose and pinching the metal strip reduces fogging. Switching to contacts on fluoro days can help clinicians who wear glasses because placing goggles over glasses can create a poor seal and less protection. The good news is our radiologists now have their own leaded eyewear. We’ve used ours for about seven years in acute care, and as the radiologists recognized how frequently they were in the suite with us, they adopted routine eye protection for themselves as well.

In short, I match the modality to the clinical question, prepare the patient and team to minimize radiation while maximizing diagnostic yield, and use meticulous PPE and workflow practices to protect the patient and staff.

Shielding

I never turn my back to the X-ray source. I intentionally position myself and the patient to avoid exposing my back because the front of my apron provides the primary protection. Nothing vital is exposed in front—my shoulders may be slightly uncovered, but my thyroid, heart, intestines, and reproductive organs are shielded. The back is different. On my apron, the straps cross into an X in the rear, leaving unshielded areas. If I turn around to grab barium and the radiologist pulses the beam—which has happened to me—the back of my body and those organs are at risk. So I plan the room layout, supply placement, and communication with the fluoroscopy team to minimize any need to turn away once the beam is active.

People often ask where to purchase radiation goggles and glasses. I don’t have a preferred vendor. I recommend going through your management or purchasing department; if they’re unsure, consult the radiologists, who usually know the approved options for your facility. That’s a great question worth pursuing, so everyone has appropriate eye protection.

Lead gloves are a hot topic. Based on what I reviewed, including a 2010 source, lead gloves may be contraindicated for our routine VFSS tasks. When you introduce lead into the primary X-ray field, the system attempts to penetrate it to produce an image. That interaction can increase scatter, potentially raising exposure to the clinician and the patient. It’s similar to why bone appears darkest on an X-ray—denser materials absorb more, altering how the beam behaves. Therefore, I do not recommend using lead gloves in the beam during swallow studies. Instead, I keep my hands out of the primary field, use tools and positioning that don’t require manual support under fluoro, and rely on proper shielding, distance, and time management to reduce dose.

In practice, I set up the suite so I can face the source and the patient, confirm we have all materials within forward reach, coordinate with the radiologist before each pulse, and avoid any mid-study reorganization that would make me turn around. With deliberate positioning, clear communication, and appropriate PPE, I can protect myself and the patient without compromising the quality of the study.

Distance and Location

Distance and location sound like common sense, but they can be hard to maintain during a swallow study because I’m close to the patient and often assist with feeding. Still, increasing my distance from the source significantly reduces dose—the farther I am from the primary beam, the lower my exposure. So, when feasible, I stand back.

Here’s how I operationalize that. After setting up and reviewing the plan, I’ll present the bolus, then take a few steps back and cue, “Fluoro on.” This gives the patient a moment to initiate while I’m farther from the beam. If the patient is quick to swallow, we may miss the onset, so I adjust based on their pace and cognition. If the patient can follow directions, I may have them hold the bolus in their mouth until we’re ready, then trigger fluoro at the exact moment. When appropriate, I also encourage self-feeding so I can remain at a greater distance while still capturing the necessary views. It’s always patient-specific, but with planning and clear cues, I can maximize distance without compromising the diagnostic value of the study.

Radiation Scatter Patterns

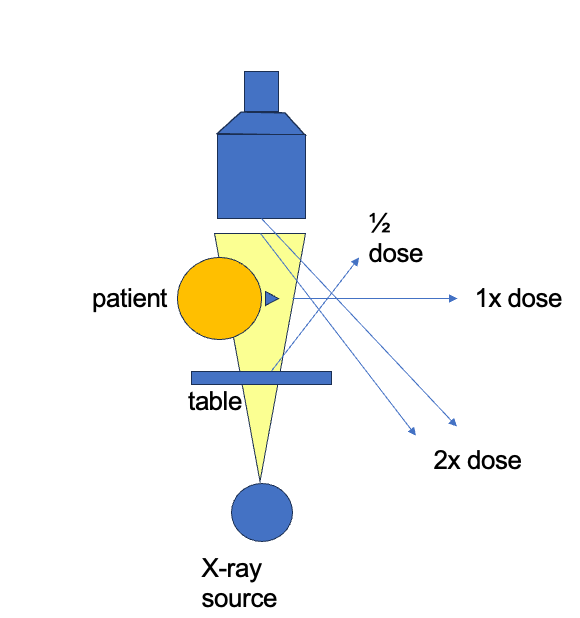

Figure 6 looks at radiation scatter patterns. This is really important for our purposes as speech language pathologists and for where we stand in each of the swallow studies. As I said before, knowing the X-ray source is really important. In the typical setup that I showed you pictures of, there's the table over here, and we're looking down on the patient.

Figure 6. Illustration to show radiation scatter patterns.

When I set up the room, I picture the scatter pattern before we begin. The patient faces the image intensifier, with the X-ray source opposite it, and the radiologist typically at the top of the setup. If I stand directly before the patient, I’m in the highest scatter zone and take the greatest dose. If I stand alongside the radiologist, my exposure drops substantially. If I move to the opposite side, to the patient’s left in this configuration, exposure can increase—about double—based on how scatter wraps around the source and intensifier. With that in mind, I plan to stay near the radiologist’s side and avoid the high-scatter areas.

Feeding is always a balance between care and safety, and I aim to keep my hands out of the beam entirely. Even though hands have higher occupational limits, putting leaded gloves in the primary field can increase scatter and potentially raise dose to me, the patient, and others. I don’t rely on lead gloves during VFSS. Instead, I prepare so that once fluoro is on, my hands are already clear. I preload utensils or cups so the patient can self-feed, use straws or syringes to deliver a bolus quickly and withdraw before the pulse, and cue patients who can follow directions to hold the bolus in their mouth until I’ve stepped back and we call “fluoro on.” I place supplies within forward reach so I don’t have to turn or reach across the beam, and I confirm “fluoro off” before any adjustments that might bring my hands into the space. With deliberate positioning and clear communication, I can capture the study effectively while staying in the lower-scatter zone and minimizing exposure for everyone.

Optimal Location for Adult VFSS/MBSS

In an adult VFSS, I aim for a setup that lets me stay in the lower-scatter zone while maintaining clear access to the patient and supplies. In the photo I took during one of my studies, it’s a tight squeeze. The patient sits in the chair with their feet toward the bottom of the frame, and I stage the barium table just to my side for quick access. I position myself on the same side as the image intensifier and radiologist, so I’m not directly across from the X-ray tube. The tube is behind the table on the opposite side from where I’m standing, so by staying on the intensifier side, I reduce my scatter exposure and avoid turning my back to the source. Before we start, I ensure everything I need—barium, utensils, towels—is within reach so I can face the patient and intensifier the entire time. That way, when I cue “fluoro on,” I’m already in the safest position, the patient is ready, and we can proceed efficiently without unnecessary repositioning or exposure. Figure 7 shows the setup.

Figure 7. Set-up for the adult VFSS/MBSS.

That wheeled unit is our TIMS machine, which lets me label and organize clips in real time as we conduct the study. By positioning myself on this side, I can access the barium and feed the patient without exposing my back to the source, and I stay on the same side as the radiologist for lower scatter.

I use a ceiling-mounted portable shield in another fluoroscopy suite, as shown in Figure 8. I position the clear panel in front of my face with the apron hanging, then reach around the shield to deliver the bolus. That setup lets me maintain a protective barrier while keeping my hands clear of the beam during active fluoroscopy, so I can feed efficiently and safely without turning or stepping into higher-exposure zones.

Figure 8. Ceiling-mounted portable shield.

Using the ceiling-mounted shield in front of my face gives me complete protection to the face during active fluoroscopy. It’s an excellent barrier when the geometry of the room and the patient setup allow it. Access is limited: if the shield is too bulky or makes it difficult to reach and feed the patient, it can become a barrier to care. In tight spaces or with patients who need more hands-on assistance, I weigh whether the shield impedes safe, efficient feeding. There are adaptations for pediatrics, and I’ll cover how I position the shield and myself to maintain protection while still getting close enough to support younger patients.

To develop these recommendations, I interviewed SLP colleagues and radiologists to gather workflow and physics perspectives. Their insights helped me refine how I position myself, manage timing cues, and use shielding to balance image quality, patient safety, and staff protection.

Optimal Positioning for Peds VFSS/MBSS

From the radiologist’s perspective, pediatric patients typically receive less radiation simply because of their size and anatomy—smaller bodies mean smaller fields and lower exposure settings. When appropriate, I involve parents in feeding during pediatric studies. I make sure they’re fully gowned with thyroid, chest, and pelvic protection, and I confirm pregnancy status per protocol when age triggers that question. I coordinate closely with the radiologist to get positioning right from the start; good geometry and clear cues reduce both exposure time and scatter for the child and the team.

I also use patient shielding when feasible—pelvic aprons for younger children and mobile lead curtains when the room allows. I like the movable wall-style shield because I can position it to protect my face and upper body while still reaching around or through it to deliver the bolus. From the SLP side, though, I have to account for feeding mechanics: infants are often fed on their left side to mitigate reflux due to stomach anatomy, and that positioning can make feeding through a curtain awkward. With practice and preplanning, it’s workable, but it requires deliberate setup and choreography. I lean heavily on family participation when appropriate and am meticulous about “fluoro on/fluoro off” communication so the beam is only active when we’re truly ready. For pediatrics, we aim to keep total fluoro time under two minutes.

Positioning remains my primary control for dose reduction. I never put my head or torso into the field, and I rehearse my stance and reach before the study so I don’t drift into higher-scatter zones. I ensure everyone is in the appropriate lead and confirm the shielding and geometry with the radiologist before the first pulse. Collimation is a powerful tool: I advocate for cone down to the smallest field that still captures the required anatomy and avoids the eyes whenever possible. In our teaching hospital, I sometimes prompt less experienced radiologists to pan down or tighten the field; that quick adjustment reduces dose and scatter. I also avoid magnification unless it’s critical for answering the clinical question. I admit I like to zoom when chasing trace aspiration along the arytenoids, but I do it knowing that magnification increases dose, so I keep it brief and purposeful.

Preparation is what keeps exposure low without sacrificing diagnostic value. I explain the procedure to parents and patients in advance, perform a careful chart review and oral mech, and decide which maneuvers and strategies I’ll trial—then I practice them with the patient. Hence, the exam runs smoothly with minimal retakes. When endurance is part of the question, I structure the 30-minute slot to capture change over time: I’ll acquire initial swallows, pause the barium, have the child or patient eat non-barium food for several minutes, then reintroduce barium to see whether fatigue unmasks aspiration or inefficiency. Throughout, I coordinate timing with the radiologist to pulse only when needed. With deliberate positioning, vigilant collimation, and clear communication, I can keep the dose as low as reasonably achievable while still answering the clinical questions that will change care.

Time

Time and dose are always a risk–benefit decision. On certain fluoroscopy units, there’s more space between the X-ray source at the bottom and the image intensifier above. In those suites—like our first-floor room that accommodates beds—I can extend the C-arm and position the patient closer to the image intensifier and farther from the source. That geometry reduces patient dose while preserving image quality.

With that setup in mind and to answer the earlier question, I stand on the intensifier side next to the radiologist, across from the source, where scatter is lower, and I can still feed efficiently. I’ll reach my hand around the edge of the grid or intensifier to deliver the bolus, then step back as we activate the fluoro. This position lets me keep my front-facing lead toward the beam, avoid turning my back, and maintain the ability to assist the patient while minimizing exposure for both of us.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I use a combination of strategies to reduce radiation risk without compromising the quality of the exam. I ensure adequate shielding—well-fitted lead apron, a high, gap-free thyroid guard, and leaded goggles—and I’m deliberate about time by coordinating closely with the radiologist to pulse “fluoro on” and “fluoro off” only when we’re ready. I position myself on the intensifier side next to the radiologist, across from the X-ray source, and I plan the room to face the beam with my front protection and avoid turning my back. I prepare with the patient and family in advance, complete a careful chart review and oral mech, and practice the strategies I intend to trial. Thus, the exam proceeds smoothly with minimal retakes. With preparation, shielding, optimal positioning, and tight coordination, I keep exposure as low as reasonably achievable while still answering the clinical questions that drive care.

References

Please refer to the handout.

Citation

Giza, T. (2025). Radiation safety and the SLP. Continued.com - SpeechPathology.com, Article 20756. Available at https://www.speechpathology.com/.