Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify the central role of debriefing in the simulation learning process.

- Explain the three core principles of effective debriefing as they relate to adult learning theory.

- Identify two debriefing methodologies.

Practical Approaches for Engaging Simulation Learners

I appreciate your interest in exploring best practices for simulation debriefing. I am very passionate about the debriefing process and look forward to discussing it with you. In my role at Simucase, I work directly with graduate programs and provide clinical supervision to students across the nation. This experience has given me a deep appreciation—and a few hard-won lessons—about what truly turns a simulation into durable, real-world learning.

I wanted to share practical tips about how to make the most out of your debrief sessions. Running a great simulation is only half the battle. The real challenge is ensuring that simulated learning experience translates into sound judgment and behavioral change when your students face their next client.

In our course today, we will review research on why debriefing is the engine of learning, break down a practical “Debriefing Toolbox,” and explore specific, easy-to-implement methodologies such as Plus-Delta and Advocacy-Inquiry to keep your learners engaged, even over Zoom. While Simucase is used to reference case studies, the strategies discussed are fully applicable to any simulation format, whether virtual or in person, in a classroom or a dedicated lab

When does the most learning occur during a simulation experience?

When does the most learning occur during a simulation experience? You might assume it happens during pre-work preparation or while students are immersed in the scenario itself. However, evidence tells a different story: the majority of learning occurs after the simulation—during structured debriefing. The simulation itself is essential because it creates an immersive experience and sets the stage for meaningful learning. But it's the post-event where structured reflection transforms experience into expertise, helping students develop both clinical skills and sound judgment.

Why Reflection is Key

Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle: Learning is a cycle where concrete experience is followed by reflection, which leads to conceptualization and application. Without this deliberate space to reflect, the experience rarely crystallizes into durable behavioral change.

Research Consensus: Scholars such as Fanning and Gaba (2007) argue that the experience itself isn't learning; rather, it is the sense-making that follows the experience that deepens understanding.

Standard of Best Practice: In 2021, the INACSL (International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning) affirmed that debriefing is not optional—it is the expected standard and the central driver of high-quality simulation education.

Debrief is the engine of learning in simulation. It takes the raw, intense experience and translates it into transferable knowledge and skill.

Adult Learning Theory in Debrief

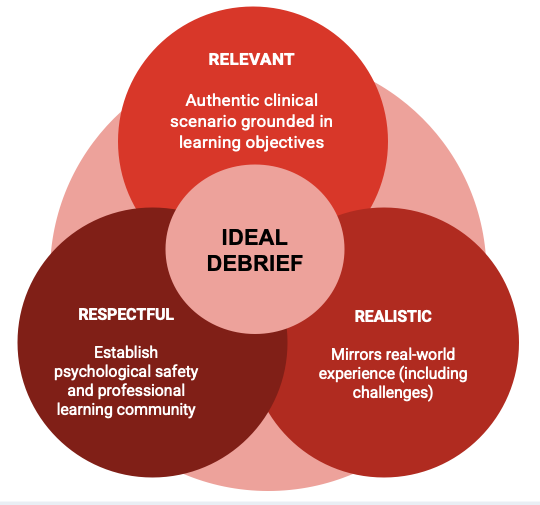

Figure 1. Adult learning Theory in Debrief.

When considering what should occur during a debrief, we draw on the principles of adult learning theory. Three essential elements guide this process: relevance, realism, and respect. Together, these create the foundation for meaningful learning and professional growth.

- Relevance: Knowles reminds us that adults engage most effectively with learning when it clearly connects to their needs, goals, and prior experiences. In a debrief, this means intentionally linking the stated learning objectives to the clinical decisions participants faced in the simulation.

- Realism: Both Kolb’s and Jeffries’ frameworks emphasize the value of authentic, practice-based experiences. The simulation should reflect real-world challenges, and the debrief should focus on applying new understanding in future clinical situations. This bridge between simulation and actual practice is where deep, lasting learning occurs.

- Respect: Respect serves as the foundation for psychological safety. A respectful environment allows learners to engage in honest self-assessment and reflection. Facilitators promote this by establishing clear norms, assuming positive intent, and using advocacy–inquiry techniques.

The INACSL Standards integrate these principles, emphasizing that effective debriefs connect to objectives, honor the learner, and feel authentic to real-world practice.

Debriefing Toolbox

- “Just right” prebrief

- Language to establish psychological safety

- Pick a debrief method

- Anchor in objectives

- End with transfer

I would like to share a few ideas related to what I call a debriefing toolbox. When we think about what we expect from a debrief, our goal is always to set students up for success. That process begins well before the simulation itself—with the pre-brief.

Before starting a simulation, we want to provide learners with what I like to call a “just-right” pre-brief. This means offering the right amount of information and support to prepare them for the learning experience ahead—enough to orient them and reduce anxiety, but not so much that it limits discovery. In my experience, the stronger and more thoughtful your pre-brief, the more effective your debrief will be because a well-prepared learner is better able to reflect, engage, and grow during debriefing.

Once the simulation is complete and we transition into the debrief, keep several essential principles in mind. The first is to set the stage for success by establishing psychological safety. Learners will not open up if they feel judged, shamed, or unsafe. Establish ground rules at the beginning of the debrief by reminding students this is a learning space, that mistakes are both expected and valuable, and that feedback is meant to foster growth rather than punishment. When I debrief students, I often tell them, “We are here to learn together—it is okay not to be perfect.” Simple phrases like that go a long way in reducing anxiety and encouraging honest reflection, especially when discussing moments that didn’t go as planned.

The next key step is to choose a debriefing method. There isn't one “perfect” or universal approach. The best method depends on your learners’ level, the complexity of the simulation, and the session’s goals. What matters most is intentionality—selecting a structured approach and committing to it, rather than improvising. A consistent framework helps guide the discussion and ensures learners get the most out of the experience.

Third, it is essential to anchor the conversation in your learning objectives. It is easy for discussions to drift into unrelated stories or side topics during debriefs. When that happens, gently bring the conversation back to the stated objectives. I often remind students what I hope they will take away from the experience to keep the focus clear and purposeful.

Finally, we always want to end with a transfer. This is where the true power of debriefing lies—helping learners connect what they have learned to real-world practice. Ask questions like, “How will you apply what we discussed today to your next client—or even to a client you haven’t met yet?” When learners articulate the “so what” of their experience, they bridge the gap between simulation and clinical practice.

To summarize: start safe, pick your method, anchor in objectives, and finish strong with transfer to practice. When these elements come together, debriefing becomes not just a review of what happened, but a transformative learning experience that prepares students to think critically and act confidently in the real world.

Goldilocks Principle of Prebriefing

Prebriefing, a key debriefing tool, should follow the Goldilocks principle: providing just the right amount of support before simulation-based learning. Too little support increases anxiety and guesswork, while too much risks spoon-feeding and dulling the experience. The prebrief must be calibrated to the learner, considering four key areas.

- Academic experiences: What coursework have they completed? Understanding this helps us gauge their foundational knowledge.

- Clinical experience: What have they actually done in practice and at what level of independence? This helps us tailor scenarios and discussions to their skill level.

- Background knowledge: Are there prerequisite concepts, protocols, or procedures we need to review to ensure learners have the necessary knowledge to succeed in the simulation?

- Previous simulation experience: Have learners participated in simulations before? Do they understand the debriefing roles, norms, and expectations?

By asking these questions, we can ensure the prebrief orients learners without removing the challenge and opportunity for independent learning that makes simulation so powerful.

Same Case, Very Different Prebriefs…

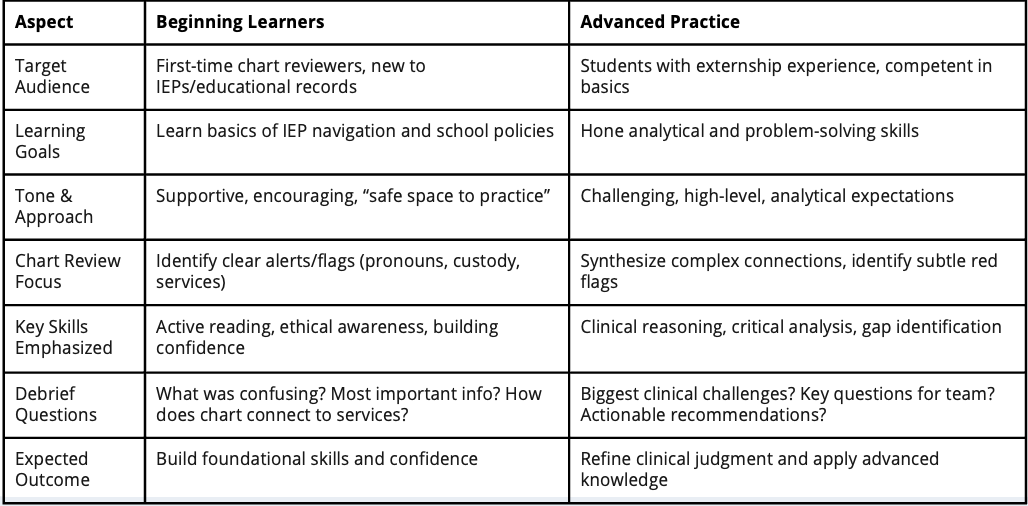

Figure 2. Beginning Learners and Advanced Practice.

To modify the prebrief to meet learners' needs, let's consider a simulation using the Electronic Documentation School Setting Part Task Trainer from Simucase, where students review school documentation. This case is interdisciplinary, but I will show two different prebrief approaches for the same case, tailored to the learners' experience. Refer to Figure 2.

If I were prebriefing a group of beginning learners—for example, first-semester graduate students who have little hands-on experience in schools—I might say something like this

"Next week, we’ll work with the Electronic Documentation School-Setting Part Task Trainer. In this case, you’ll have the opportunity to review an educational record and explore an IEP in a safe and supportive environment. The focus should be on learning, not perfection, so approach this as a chance to build your skills and confidence as you navigate these documents. You’ll be reviewing the IEP for Kai, a 12-year-old student with complex medical needs. Pay close attention to the details, including the services they are receiving, custodial considerations, and pronoun use. As you work through the case, focus on being an active reader: treat the record like a puzzle and notice any alerts or flags that might impact Kai’s educational experience. Keep ethical and legal principles, like privacy and confidentiality, in mind throughout.

At debrief, be prepared to reflect on what you found challenging, the most impactful pieces of information in the educational record, and how the IEP connects to Kai’s overall educational journey. Remember, this is about practice and growth—dive in and do your best."

When I’m assigning this simulation to students who are further along their academic journey—perhaps they have had placements in schools or worked with school-age clients—I might say something like:

On the other hand, if I’m assigning this simulation to students who are further along in their academic journey—perhaps they have had placements in schools or worked with school-age clients—the pre-brief would look different. For this group, I might say something like:

"Next week, you’ll be completing the Electronic Documentation School-Setting Part Task Trainer simulation, building on your previous externship experience. I want you to think about how this simulation will challenge your clinical reasoning and problem-solving skills beyond a basic document review. Focus on synthesizing how Kai’s diagnosis, educational history, and services all connect. Be attentive to underlying issues or red flags that could impact an IEP meeting as the team works together.

Analyze the IEP goals and interventions to determine whether they align with Kai’s needs, and look for potential gaps in services. In the debrief, be prepared to discuss the most significant clinical challenges, the questions you would pose to Kai’s team to gain deeper insight, and concrete, actionable recommendations to strengthen support for them. This is your opportunity to sharpen your clinical judgment using a real-world scenario."

This example illustrates how the pre-brief should vary based on learner level, even for the same case. For beginners, the focus is on orientation, foundational skills, and confidence-building. For more advanced learners, the emphasis shifts to critical thinking, synthesis, and clinical decision-making.

Establishing Psychological Safety

The next critical element of effective simulation is establishing psychological safety—the foundation of meaningful debriefing and team learning.

When learners feel safe, they are more likely to speak up. They share honest feedback, admit mistakes, and ask questions without fear of judgment. This shift from blame to understanding enables us to examine the root causes and learn from errors rather than hiding them.

When we provide a genuinely safe environment for students to process what happened, we help them reset emotionally. This matters because we know that safety must come first—learning follows naturally once students feel secure enough to engage fully in reflection.

Establish Safety and Revisit Norms Often!

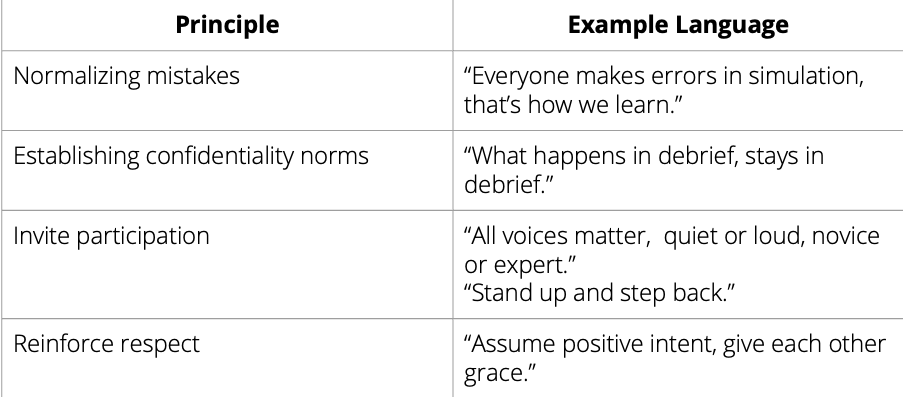

I am sharing some of the language I use in my debrief groups to help establish psychological safety, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Example Language chart.

I would like to share some of the language I frequently use in my debrief groups to help establish psychological safety (see Figure 3). To promote psychological safety in debriefs, I normalize mistakes by explaining that errors are expected in simulation and are essential for learning, both individually and collectively.

Another important component is establishing confidentiality norms. I often say, “At the risk of sounding cheesy, what happens in debrief stays in debrief.” This helps create a privileged learning space where everyone knows that conversations are private and respected.

I also prioritize inviting participation from all learners, including those who may be quieter. I tell students that all voices matter—loud or quiet, novice or expert—and that we want to hear everyone’s reflections. One of our supervision team members often uses the phrase, “Stand up and step back.” That is, speak your perspective, then step back to allow space for others to contribute.

Finally, we reinforce respect and positive intent, especially if discussions become tense. I often remind students, “We assume positive intent and work together. We give each other grace.”

By introducing these psychological safety cues at the start of debrief and circling back to them as needed, we create a focused, respectful, and open environment. This allows learners to engage in honest reflection and delve deeply into the content of the simulation, ultimately supporting meaningful learning and growth

Common Debriefing Methodologies

Plus Delta Debriefing

Next, I would like to spend a little time discussing common debrief methodologies, which can be applied to any type of simulation—not just Simcase. One of my favorite approaches is the Plus-Delta debriefing method. In Plus-Delta, we divide the discussion into two parts: the Plus, where we focus on what went well, and the Delta, where we focus on areas for change or improvement.

On the Plus side, we highlight strengths and effective behaviors. This isn't just "fluff"—it makes good practices visible so learners can repeat them. For example, if a learner were completing a pediatric speech assessment case, they might say:

"I did really well when collecting Hadley’s case history. When I came across her genetic diagnosis, I wasn’t sure what it was, so I researched it and how it affects her speech. This preparation helped me address the family’s concerns effectively."

This is a concrete success we want to reinforce and carry forward.

Next, we move to the Delta side—the improvement column. Here, the focus is on identifying something that didn’t go as planned and turning it into a clear, actionable step. For instance, a learner might reflect:

"I had difficulty scoring Hadley’s Goldman-Fristoe test of articulation because I used the wrong raw score, which led to an incorrect standard score. Next time, I will slow down and review IPA transcriptions carefully before scoring."

Notice the structure: there’s a specific gap identified and a specific action step to address it.

There are two key rules that make Plus-Delta work effectively:

- Start with the Plus: Highlighting strengths first creates a positive, supportive environment. Learners respond better when we acknowledge what they did well before discussing areas for improvement.

- Make Deltas actionable: Any area for improvement should include a concrete next step—what exactly will the learner do differently in the future?

Used consistently, Plus-Delta helps teams celebrate successes, identify areas for growth, and create a clear roadmap for improvement. It also promotes a positive, non-judgmental environment and encourages honest, constructive feedback during debrief sessions.

Gather - Analyze - Summarize (GAS) Approach

Another debrief approach I commonly use is called the GAS approach, which stands for gather, analyze, summarize.

In this method, we first gather information. This involves exploring the learner’s feelings, perceptions, and observations of what actually happened during the simulation. The goal is for learners to feel heard while reinforcing respect and fostering a sense of psychological safety. It also gives the facilitator insight into how learners interpreted the scenario.

Next, we analyze. Here, learners engage in reflection and critical thinking, considering why they made certain decisions and exploring alternative approaches. This step aligns closely with Kolb’s reflective observation and abstract conceptualization phases, allowing learners to deepen their understanding of the experience.

Finally, we summarize. This step consolidates key takeaways and connects learning to real-world practice, supporting transfer of knowledge to future clinical scenarios.

The GAS approach is simple, structured, adaptable, and promotes meaningful reflection. Its three-step framework makes it an excellent, easily implementable method for facilitators new to simulation-based learning.

Advocacy - Inquiry Method

Another approach you can use to debrief simulations is the Advocacy-Inquiry method. With advocacy, we clearly identify and describe our observations, and then move into inquiry, where we explore the learner’s reasoning.

For the advocacy step, you focus on specific observations and share your interpretation using “I” statements. Because we often review simulations after they have occurred, we can gather this information from learner transcripts. For example, using a speech sound assessment case in speech pathology, I might say:

"I observed that several of you had difficulty differentiating your patient's speech sound disorder. Many attempted to diagnose both articulation and phonology. I am concerned we might be conflating overlapping features, treating them as identical."

The key here is to be specific and objective while avoiding labeling any learner as right or wrong. This establishes a neutral and constructive tone for discussion.

Next comes inquiry, where we express genuine curiosity about the learner’s thought process. For instance:

"I’m wondering what your reasoning was as you weighed these two diagnoses. What cues in this case guided you one way or another? Can you help me understand which information or evidence felt most persuasive?"

The goal of inquiry is to surface assumptions and decision-making pathways in an open and nonjudgmental way. This approach not only reveals clinical reasoning but also creates conditions for self-correction, helping learners reflect on their decisions and improve future performance.

Tips from The Simucase Supervision Services Team

Next, I want to share some tips from the Simucase Supervision Team. Our team regularly leads debriefs for graduate students. I asked our supervisors: “If you were offering advice to a new faculty member just learning how to debrief, what would you share?” Here are some of their responses:

- Connect cases to real-life experience: Sharing anecdotal clinical experiences to help learners see how the case relates to real-world practice. This helps students understand the practical relevance of what they’re learning.

- Role-play communication: Learners can practice explaining their findings. For example, “How would you explain these results to the family? How would it change if you were presenting to a teacher?” This encourages learners to reflect on their language and communication strategies in various contexts.

- Manage tangents effectively: Another supervisor noted that discussions can easily go off track. To refocus, she often uses the “parking lot” approach: “That’s a great point—let’s put that in the parking lot and come back to it later.”

Embrace silence: One of the most important tips is to recognize the magic in silence. When a question is posed, resist the urge to immediately fill the space. Waiting 5 to 15 seconds can feel uncomfortable at first, but it gives learners time to think and reflect. Over time, you’ll see that this pause often leads to more thoughtful responses.

These tips, drawn from experienced supervisors, can help new faculty build confidence, structure discussions effectively, and foster meaningful reflection during debrief sessions.

I also asked our supervision team about their favorite debrief questions, and I wanted to share some of those with you. Again, these questions are great for debriefing Simucase content but can also be applied to any simulation, whether completed in a lab or classroom. One of my personal favorites is:

"If you could go back in time and offer yourself advice—a fast rewind to a week ago—what would you tell yourself? What do you wish you had known before starting this simulation?"

Other questions shared by supervisors include:

"How might this experience change the way you approach a similar patient in the future?"

"How did the information you gathered in the case history section influence your assessment and treatment plan?"

"What surprised you or caught you off guard when you were working on this case?"

These questions often uncover hidden assumptions or gaps in understanding, providing valuable insight that can be addressed in the debrief discussion.

Final Thoughts

Debriefing is a deliberate, structured process intended to foster reflection, critical thinking, and skill development by connecting theory to practice and identifying growth areas in a supportive environment.

High-quality debriefing starts with a prebrief that sets clear expectations and prepares learners. The debrief itself relies on psychological safety and structured methods (e.g., Plus-Delta, GAS, Advocacy-Inquiry) for meaningful dialogue, self-assessment, and collaborative learning.

Engagement, especially in virtual settings, is vital. Varying methods like polls, breakout rooms, and role play maintains attention and promotes participation. Pacing, acknowledging strengths, and analyzing challenges enhance confidence and clinical reasoning.

Debriefing also models professional behavior. Faculty demonstrating curiosity and respect helps learners internalize these traits, improving communication and decision-making. Encouraging learners to articulate their reasoning surfaces gaps and strengthens lifelong learning.

Finally, effective debriefing is iterative, flexible, responsive to group needs, and grounded in evidence. Thoughtfully integrating pre-briefing, engagement, structured methods, and supervision creates powerful, lasting impacts on clinical competence and professional growth.

Ultimately, debriefing is where real learning happens: reflection meets action, moving learners from observing to understanding and doing.

References

A complete reference list is provided in the course handout.

Citation

Ligon, E and Vela, F. (2025). Practical approaches for engaging simulation learners during simulation debriefing. Continued.com - SpeechPathology.com, Article 20768. Available at https://www.speechpathology.com/