Editor’s Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, “Caregiver Training for Individuals Caring for Patients with Dysphagia,” presented by Debra Suiter, PhD, CCC-SLP, BCS-S.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List at least 3 challenges caregivers and clinicians face when communicating about patient care.

- Describe the roles of the caregiver and clinician as described in the Patient-Centered Model of Care.

- List the three components of the CARE Act.

Introduction

In this course, I will be talking about caregiver training, specifically focusing on training caregivers who are taking care of individuals with dysphagia. However, many of the concepts are applicable to other patient populations as well.

I will first address challenges. When we talk about caregiver training, there are certainly challenges that caregivers face, but there are also a number of challenges that we, as healthcare providers, face as well. Then I will discuss the caregiver and the health care provider roles, and conclude with a few case examples to show how we might provide training for caregivers in each of these scenarios.

Challenges

Let's start with the challenges. If we're talking about critically ill patients who are coming to us to receive services for dysphagia, often those individuals are unable to communicate with their healthcare providers or participate in care decisions, depending on their underlying diagnosis. For example, if they're in an acute care setting, if they've been recently involved in a motor vehicle accident, or they have altered levels of consciousness they may not be able to actively participate. If they have underlying language or cognitive issues, they may not be able to participate. Therefore, the responsibility for making decisions related to healthcare often falls on surrogate decision-makers and it’s a real challenge when we ask somebody who's not the patient to make decisions on behalf of the patient.

Out of the 15.2% of older adults who are hospitalized each year, about 1/5 (20%) will have an adverse event in the three weeks following discharge. That's often attributed to the fact that many patients don't understand how to follow through on their care once they're discharged home. However, when caregivers are included in discharge planning, the risk of 90-day readmissions to the hospital decreases by about 25 percent. That's pretty impressive. Again, this further delineates the need to involve caregivers in conversations that we're having to ensure that caregivers are properly trained and they understand what's being asked of them once the patient is being discharged to their care.

One of the biggest challenges is that the communication regarding a patient's care across settings is often fragmented. I've worked across a number of different settings over the years (acute care, skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehab) and at each of those levels of care sometimes information is not communicated. For instance, if you're in a skilled nursing facility and a patient's been discharged to your facility, they may have had a modified barium swallow study completed at the acute care facility. But perhaps you don't have access to those records. It's very difficult to implement plans of care if you don't have complete communication regarding what the previous levels of healthcare are.

The patient and the caregiver are often the only common threads across settings. So, oftentimes, we are relying on them to provide information and we're relying on the accuracy of that information. Therefore, we hope that they have a good understanding of what’s happening, but they may not.

Another big challenge is that caregivers generally have expressed wanting a larger role in healthcare decision-making, and they want healthcare providers to be more responsive to their needs. However, there have been reports in which caregivers have stated that they often feel as if they're uninformed, and they're disenfranchised from clinical decision-making. Decisions are being made and they don't feel like their input is being valued or being heard. What can we do to make caregivers feel as if they're part of the team and are making informed decisions on behalf of their loved ones?

The Challenge: The Caregiver

“Family caregiver or “informal caregiver”. Let's talk about who the caregiver is. Most of us have a fairly good understanding of it, but there are terms in the literature that will talk about “family caregiver” but caregivers are not always necessarily family members. There is also the term “informal caregiver” who are not trained or licensed providers of care. These are unpaid family members, friends, or other individual who provides care to individuals with chronic or acute conditions.

The care that we're asking these individuals to provide can range quite a bit in terms of complexity. We may ask them to provide assistance in terms of activities of daily living, including bathing and dressing. I was going to say that these types of ADLs don’t require much training, but depending upon the physical limitations of the patient, they may require a great deal of training to ensure that they are done safely and adequately. Additionally, oftentimes we're also asking caregivers to provide more advanced care, such as assistance with tube feeding and ventilator care.

I've been a speech pathologist for almost 30 years at this point, and to be honest, I'm not sure if I were asked to provide care for my loved one with tube feeding, that I would feel confident to be able to do that and do that well. Yet, we're asking caregivers who may not have any experience, may never have seen a feeding tube before, and we're asking them to take over the care of this individual at home. That is oftentimes stressful for those caregivers.

Statistics. In 2015, approximately 43.5 million caregivers in the United States provided care to an adult or a child with limited ability to complete activities of daily living. The estimated cost of this is huge. It's approximately $470 billion worth of care. This is attributed to these unpaid contributions. That is a huge number and a huge value that we're attributing to the care being provided by these caregivers.

Additionally, one in five adults is placed into the role of caregiver for their family members or other loved ones. In the United States, the average caregiver is a 49-year-old-woman, which is important because we need to think about the context of this individual. So, a 49-year-old-woman who may or may not have children, who may or may not have a spouse, and who typically works outside of her home.

Assuming that this individual is working a full-time, 40 hour a week job, they're spending nearly 20 hours per week providing unpaid care. The care is typically provided to the individual's mother for nearly five years. So, there are a lot of factors at play here. There are other demands on this individual's time, other roles this person plays, and on top of that, now they're being asked to provide up to 20 hours per week of unpaid care. Obviously, it's not all women who are providing care. Approximately 40% of caregivers are men.

Responding to the illness of their loved one. There are, again, a number of challenges that caregivers face. The biggest one is how they are responding to the illness of their loved one. For instance, if the individual is coming into an acute care facility through the emergency department because they've been in a motor vehicle accident, had a stroke, or some other acute illness, the first thought in the caregiver's mind may be, “Is my loved one going to survive? If they're going to survive, how are they going to be after they've survived? Are they going to be the same individual that I knew prior to this illness or accident, or what will they be like?” It may simply be, “Are they going to live through this? Are they going to be okay?”

The caregiver may be very overwhelmed. A lot of our caregivers are not familiar with medical settings. Many of our patients come from areas that are three or four hours away from our facility. Where we are is considered a large city for many individuals, so it's overwhelming to come here. They walk into a hospital with a lot of people with whom they may not be familiar. They may not understand who's in charge of the situation in terms of the medical team, so it may be very overwhelming for them. They may be fearful. They may be sad. Anger can be a huge reaction, especially if the individual was injured because of lifestyle choices with which the caregiver did not agree. Perhaps there is some anger that's there on the part of the caregiver as well.

We need to consider how the relationship was with the patient prior to the illness, whether it is acute or chronic. I work in an ALS clinic and oftentimes our patients’ caregivers are ex-spouses or they were in strained relationships prior to the introduction of this illness. How does that figure into the caregiver's receptiveness to information that we're providing to them? How eager is the caregiver going to be to assume the role of caregiver? What else is going on in this relationship that may affect how the caregiver is able to provide care to this individual? How is the loved one responding to the illness? Again, if you're working in a situation where patients are being given diagnoses that often have grim prognoses, how is their loved one responding to the illness?

I've had patients in our ALS clinic who oftentimes don't want us to use the terminology. They don't want us to use the disease name while we're talking to them. That's huge. How well the individual with the illness is responding to that illness can certainly affect the caregiver and his/her ability to receive information and be able to implement recommendations that we're making.

Responding to new roles as a caregiver. Other factors to consider are how well the caregiver is responding to their new role as caregiver, are they overwhelmed? Is this something that they anticipated taking on? Is this something that is disrupting their lives, and there's some resentment or anger? Do they feel like they are prepared to take on this role? What were the family dynamics like? What were the dynamics like with the individual and the caregiver regardless of whether or not they are family? What other roles does the caregiver already have?

Again, if we go back to the idea that the average caregiver is a 49-year-old-female who is working outside of the home, there are demands placed on an individual because of full-time work. If they're not able to devote as much time to work, then there are stressors in terms of being able to maintain employment and living up to expectations at work, as well as providing care at home. Economic strains can certainly ensue because of that.

We also need to think about the other roles the caregiver may have. Are they already providing care for somebody else? For instance, if the caregiver has two older adult parents, they're already taking care of one, and then they take on the role of giving care for the other individual, that may be an additional stressor for the caregiver.

Finally, we need to consider how caregiver personality factors into this. Is the caregiver somebody who's very stoic and is just going to take things as they come? Are they able to absorb the information, jump in right away and go about the business of providing care for the individual? Is this somebody who is already very anxious and doesn't feel confident in their ability to provide care to the individual? How does this personality factor into how well they're able to assume the role of caregiver and absorb the information that we're providing to them?

Symptoms of anxiety and depression are common in caregivers. There's some interesting information that's been published that addresses the symptoms of anxiety and depression in caregivers. It's been found that between 40 to 70% of family caregivers of older adults have clinically significant symptoms of depression, which is not surprising if you think about caregiving. Caregiving is quite demanding and can be so isolating if you're providing a significant level of care for the patient and no longer able to get out and do the day-to-day activities that you used to do. Therefore, it's not unreasonable that anxiety and depression would occur in caregivers, and interestingly, it has also been found that these symptoms can persist.

For individuals who've been in an acute care setting and in an intensive care unit, studies have suggested that symptoms of post-traumatic stress and adverse effects on quality of life were found in 1/3 (33%) of family members after ICU discharge. So, these effects are long-term. Patients are being discharged home and we're asking individuals who are experiencing the symptoms of post-traumatic stress to provide additional care.

Does the caregiver have a clear understanding of what the patient’s wishes are? This, of course, is going to be a huge stressor. Hopefully, patients have an advanced directive, but we know that often they don't. In advanced directives, patients can indicate their desire, for instance, for whether or not they would be willing to accept a long-term alternative means of nutrition. In an ideal world, patients would have had an advanced directive, but if they don't then it's left to the caregiver to try to speak on the patient's behalf and to try to advocate for the patient. Again, that can be quite stressful for the caregiver if they're not sure what the individual would want.

Did the patient designate who they wished to be their healthcare proxy? The healthcare proxy is the individual who is designated, legally, to make healthcare decisions on behalf of the patient. If the patient has not designated a healthcare proxy, by law, it falls to the spouse. If there's no spouse, it falls to the adult child, and if there's not an adult child, it falls to the parents and so on.

Again, we need to consider how the relationship was prior to their illness. Many of you may remember the case of Terry Schaivo, a woman who lived in Florida. She was, I believe, in her forties when she suffered a cardiac arrest and had an anoxic brain injury as a result of that. At the time, her husband was deemed to be her healthcare proxy.

Her parents and her husband were actively involved in the care of Ms. Schaivo. Her parents were initially okay with her husband being the healthcare proxy, and they collaborated in terms of ensuring that Terry was getting the proper care and going through various rehab facilities. But at some point during her care, there was an incidence in which Terry suffered some injuries in one of the health care facilities. The Schaivos filed a medical malpractice suit, and they were awarded over a million dollars, over which Michael Schaivo, her husband, had jurisdiction. Basically, he was in charge of the money of which the majority of it was to be used for Terry's care. But there was a considerable amount that went to Michael Schaivo as well. After that, Terry’s parents and her husband had a falling out.

The reason this is important is that at some point there was a discussion about whether or not Terry, who did not have an advanced directive, would wish to continue to live in what had been deemed to be a persistent vegetative state. She had a feeding tube, and there was discussion of whether or not that feeding tube should be withdrawn. If you remember this case, it was back in the early 2000s, and it went back and forth in the courts with the husband and the parents having considerable disagreements. Ultimately, the court sided with her husband and tube feeding was withdrawn.

This is certainly an extreme example, but it's something to consider in terms of what was going on behind the scenes with the caregivers involved in the care and making decisions on behalf of this individual.

Healthcare literacy. Healthcare literacy is something that we need to consider. Many of us have a vernacular that we use. We have language that we use. We talk about “MBS,” and we talk about “barium” and “hyolaryngeal excursion.” We use a lot of terms that are not familiar to individuals outside of our field. But, if you're around other SLPs, it seems like day-to-day language that people should understand. But they don’t.

Healthcare literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions. People need to understand the information that they're being given in order to make informed decisions regarding their health. Low health literacy is associated with a higher risk of death, as well as more emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Conversely, if individuals have a high level of health literacy, there are more desirable clinical and health administrative outcomes such as hospitalization use.

According to the US Department of Education, only 12% of English-speaking adults in the United States have proficient health literacy skills. To me, that's a shockingly low number. But the point is that when we are providing information to caregivers, we need to do so with an assumption that they probably don't understand all of the information that we're providing them.

One of the big factors that can affect healthcare literacy and how receptive caregivers are to it, is how comfortable they are around healthcare and healthcare providers. If they're caring for somebody who has been generally healthy up until the current hospitalization or current illness, they may not have much experience in health care. Healthcare facilities are large places, they're very confusing for our patients, and many patients and their caregivers don't understand the different roles of the healthcare providers, and what's being told to them. That can certainly affect how receptive and how able they are to receive information from us when we're providing training.

We need to consider how comfortable they are around healthcare providers. Do they view physicians as authoritative figures who are not to be questioned? If the physician is saying something to the patient that they don't agree with, are they comfortable asking questions? Are they somebody who is much more skeptical of information that's being provided, and they're not going to be as receptive upfront? How comfortable are they around other health providers such as SLPs? How do they view our roles?

Caregiver biases. How do the following factor in?

- Age

- Culture

- Gender roles

- Ethnicity

- Religion

- Education

- Socioeconomic status

- Communication/learning style

For example, if you are a brand-new female clinician in your twenties, how receptive would an 80-year-old-male be to the information that you're providing? Can that affect how comfortable and how well that individual is going to be able to receive information and implement recommendations that you're providing?

Culture can certainly be a source of bias as are gender roles. I have had both male and female patients over the years state explicitly that they prefer to have a male speech pathologist working with them, and then certainly vice versa.

Ethnicity, religion, education, socioeconomic status, communication and learning style can all play a role in a caregiver’s bias. I always say to caregivers when I am providing training, “I'm a very visual learner. I'm a very hands-on learner. Are you like that? How do you prefer information to be given to you? What works best for you?”

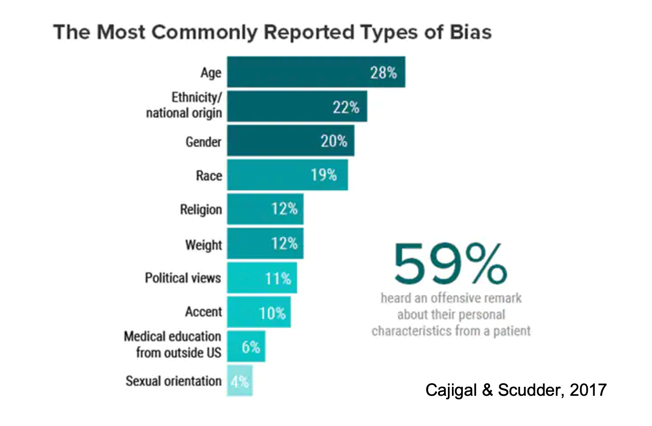

Almost 60% of physicians reported hearing an offensive remark about their personal characteristics or background from a patient within the past five years. I found these numbers interesting. These numbers are related to physicians, but could probably be generalized to healthcare providers as a whole. If you're hearing those remarks, it calls into question how you are going to feel about interacting with that individual.

Additionally, 1/3 of patients reported that they had avoided a provider based on the provider's personal characteristics. Figure 1 is a graphic representation.

Figure 1. Most commonly reported types of bias.

The figure shows that the biggest source that was cited as a type of bias had to do with the healthcare provider's age. However, you can see also included are ethnicity, gender, et cetera. Again, about 59 to 60% of physicians reported hearing an offensive remark about their personal characteristics from a patient. So, how does that affect you as the provider? How does that affect the caregiver and how receptive that caregiver will be to the information that you're giving them?

Caregiver expectations. Does the caregiver understand the patient's prognosis? I am sure many of you have experienced this. Let’s say you have a patient with profound dysphagia because they were treated for head/neck cancer with radiation treatment that was completed 20 years ago. Now they're having significant issues and at this point, therapy is not proving to be effective. Does the caregiver understand that? Do they have realistic expectations? Is it realistic to expect the patient to consume a regular texture diet? Do they understand the patient's underlying illness?

If you're working with individuals with neurodegenerative diseases, such as ALS, does the caregiver understand what the prognosis is in that situation? Do they have realistic expectations of how much function their loved one can regain or if their loved one can regain function? Unrealistic expectations may be due, in part, to a lack of appropriately delivered and accurate information on our part. So, we need to make sure that the information we're providing is not only accurate but that it's provided in a manner that the caregiver and the patient can understand.

The Challenge: The Healthcare Provider

Let’s talk about challenges that, we, as healthcare providers experience.

Healthcare delivery systems are often criticized for a lack of continuity across systems. One of the biggest challenges that I have found is getting access to medical records for patients who have received care across a number of different health care facilities that are not all under the umbrella of the health care facility in which I work. The information that's in the patient's chart and the facility in which I work may not contain critical information. I've often been surprised, for instance, to walk into a fluoroscopy suite in which I've done the case history, I've done the chart review, and on the flouro I see hardware that's consistent with the patient having had anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. But nowhere in the medical chart has that been mentioned because the patient received care somewhere else. That can certainly affect how well we're communicating information to the patients, and what our expectations are for the patient.

Healthcare systems are also criticized for shortening hospital length of stay. Patients and their caregivers often feel as if they are being rushed out of a facility before they're comfortable going home. We may feel as if we have not had sufficient time to provide the level of caregiver training that we would like to provide.

Additionally, healthcare delivery systems are offering very limited community resources for patients and caregivers once they're discharged home. When I initially planned this course, I reached out to a social worker in our facility and found out that the resources available for providing assistance to caregivers are very limited. So that can be a huge issue.

Productivity expectations. Other challenges that we may experience have to do with productivity expectations. If you're working in a facility where you have an 80% productivity expectation, some even have 90% productivity expectation, you're worried about getting the numbers. You may not be able to spend as much time with a patient and with a caregiver and provide the training that you would like to because your time is limited due to productivity expectations.

We need to consider other stressors. What are we bringing to work with us? Are there interpersonal issues at work that are affecting our attitude towards our job or our attitude towards what we're being asked to do? Are there productivity expectations that we may not feel are reasonable, and so there's some degree of stress related to that? Are there interpersonal issues with colleagues at work that are affecting your ability to provide training? Have you brought issues from home to work with you? For example, have you gotten up that morning, and if you're a parent, have you had a child who didn't want to get out of bed to go to school, so you're dealing with that stressor before you ever got to work? It's been a terrible morning at home, and then you get to work and you have to basically code switch. You have to turn off some of those stressors that you've brought from home, and not allow them to impact how you're providing care at work. That is always easier said than done, as we all know.

Clinician burnout is something I’ll address shortly but first, what are our prior experiences? Have we worked with this patient and caregiver before? Have we worked with individuals from this patient population before? How have caregivers in the past responded to us, how does that affect us, and how comfortable we are in providing training to our caregivers?

Clinical burnout. This is a huge issue. If any of you are involved in some of the social media platforms for SLPs, you can see that burnout is a huge issue among healthcare providers in general, and definitely for SLPs.

Clinician burnout is defined as “a high degree of emotional exhaustion, and high depersonalization (i.e., cynicism) and a low sense of personal accomplishment from work.” So, if you have everyday stressors, productivity expectations, or you feel like you're not able to keep up with the demands of work, that can be a source of clinician burnout.

Here is an interesting statistic, and because it's from 2020 we have to keep in mind that we are experiencing a global pandemic. In 2020, 42% of physicians reported being burned out. I would imagine that number can be generalized to SLPs as well. Again, take into account that 2020 was, hopefully, an extraordinary year that we won't have to experience again. But the pandemic was certainly an additional source of stress, and I would imagine for burnout as well.

Burnout is a huge concern because it has been found to be an independent predictor of a number of adverse outcomes, including recent major medical errors, being involved in a medical malpractice suit, healthcare-associated infection, and patient satisfaction. All of these make perfect sense, but if you're burned out and you're not invested in what you're doing with a patient, that becomes very evident to the patient. It becomes very evident to the caregiver, and that can adversely affect patient satisfaction and caregiver satisfaction as well.

Clinical personality and biases. I talked previously about how caregiver personality can affect caregiver training. We also need to consider how our personality and biases affect how we communicate with patients. Again, age is a big one. Certainly, I'm much more comfortable providing caregiver training and much more confident in my clinical skills than I was when I first graduated from graduate school. I am sure many of us feel that way. How does your age factor in? How do you feel about communicating with people who are much older than you or much younger than you?

How does gender affect your ability to communicate with other individuals? Socioeconomic status, culture, religion, education, ethnicity, and communication style, can all affect how we communicate with others.

We need to consider how comfortable we are communicating with caregivers, particularly if we perceive that the caregivers are going to be in disagreement with the recommendations that we're making. How do we communicate with others whose choices and values differ from our own? We can definitely experience this when we talk about dysphagia. For example, based on that swallow assessment, we have determined that the safest route for nutrition for the patient is a non-oral means of nutrition, and what if the caregiver disagrees with that recommendation? When patients or their caregivers disagree with us, do we view that as an affront to us or are we comfortable with that? Are we able to continue to provide care and training for that individual who does not agree with our recommendation?

Clinicians may also acquire bias based upon medical records, notes, or communication with other healthcare providers. I have seen in medical charts, I'm sure you all have too, where there have been comments made about how receptive the patient or the caregiver was to communication from a healthcare provider. That's oftentimes documented. It might also be documented in the medical charts if there has been an episode in which the patient has threatened a clinician or other issues. How do we feel walking into a situation if that's already been documented? How is that going to affect our ability to communicate with the patient or to communicate with the caregiver?

Biases about healthcare provider’s role. Additionally, we need to consider what our biases are about our role as healthcare providers. How do we view our role? Do we view ourselves as authoritative figures, "we are the specialists"? If we're talking about dysphagia, we are the individuals who specialize in swallowing, we are well-educated, and we know what we're talking about. Therefore, if I provide you with a recommendation, I expect you – the caregiver or the patient - to accept the information that I'm providing and not question it. Alternatively, do we view our role as being collaborative? Do we work closely with the caregiver and the patient to ensure that everybody is comfortable with the information and the decisions that are being made?

How do we respond if our recommendations and the caregiver's wishes differ? ASHA has explicitly said if the caregiver (again, if we talk about dysphagia, and we talk about non-oral means of nutrition and whether or not the caregiver or the patient is willing to accept our recommendations for non-oral means of nutrition, or thickened liquids) said they understand the information, and they are not going to follow our recommendations, we are not to abandon the patient at that point. We are to try to provide as much care as we possibly can, understanding the context from which we're providing that.

Finally, how confident are we in our clinical skills? That is evident to patients and to their caregivers when we're providing information. If they sense that we're not confident in what we are saying, if we don't know what we're talking about, that can affect how receptive they're going to be to the information that we're providing.

The Challenge: The Setting

Acute care facilities. There are also challenges in terms of setting. If you're working in an acute care facility, you know those are noisy places. There are a lot of people in and out, sometimes medical teams are coming in, alarms are going off, there are sounds out in the hallway. They're very busy places. With all of that going on, it might not be the most conducive environment for caregivers to be trained.

Oftentimes, there is a lot of medical equipment that caregivers are not familiar with. Multiple providers might be competing for time with the patient. Caregivers may not always understand the role of these various healthcare providers. Time with the patient and caregiver can be very limited.

If you have worked in acute care, you know that patients are often being taken off the floor for ongoing testing, so your time is often cut short. You may have planned a training session, and that gets interrupted because the patient has to go for testing on a different floor. So, there are certainly challenges just on the basis of the setting in which we're operating.

Videofluoroscopy suites. Videofluoroscopy suites are often challenging as well. In my setting, this is a shared space. I’m in an outpatient clinic, but it's also being used by our inpatient team so there's a high demand for those rooms. There are other services that are using those rooms as well. So we have a very limited amount of time with the patient and the caregiver in order to provide counseling and recommendations following a swallow study.

They can be very noisy places. There are a lot of moving parts in those suites and a lot of individuals in and out of those suites, so again, they may not be the ideal environment in which to provide training for caregivers and patients.

Outpatient clinics. Oftentimes, if you're in a multidisciplinary clinic, for instance, there are multiple providers. Caregivers and patients don't always understand what our roles are. We often have very limited amounts of time in which to see patients. For example, if you're in clinic for three hours and you have 10 different providers who need to see the patient and their caregiver within that amount of time, you are limited. You can't provide as much time and discussion as you would like in those types of settings.

Our Roles

Our Roles: The Caregiver

In terms of the caregiver, their biggest role is to advocate on behalf of the patient. Again, if the patient had an advanced directive, that's easier said than done because the patient would have explicitly stated his or her wishes with regard to end-of-life care or enteral feeding. So, it's much easier for the caregiver to advocate on behalf of the patient in that situation. But if the patient didn't have an advanced directive, it can be quite difficult, and trying to make educated judgments of what the patient would have wanted can be quite stressful for the caregiver.

They need to maintain open communication with the healthcare team. And it is our responsibility to ensure that they feel that they can maintain open communication with us as members of the healthcare team.

They should be actively participating in the patient's care. They should be able to ask questions if there's uncertainty or concerns. We need to foster an environment in which caregivers feel as if they can ask us questions and have their concerns addressed.

Participating in hands-on training is huge. If we're able to provide that hands-on training for the patients and their caregivers, that gives them an added level of comfort.

Our Roles: The Healthcare Providers

When we talk about our roles as healthcare providers, there are typically two primary means of medical decision-making that have existed over the years. One is patient autonomy which advocates that patients have the right to make decisions on their own behalf. They cannot have treatments imposed upon them, that they are unwilling or would not wish to have. So, if a caregiver is being asked to make those decisions, they may feel ill-informed or ill-equipped to make those decisions. They may need help with decision-making, but they may not understand or be able to articulate what information they need. They may not know what they don't know and be able to communicate that effectively.

The other model is paternalistic and it’s the idea that the healthcare team knows best. Patients and caregivers do not question our recommendations and we don't seek or consider the patient or the caregiver's wishes. Fortunately, that's a model that we've moved away from, for the most part.

Institute of Medicine. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine strongly recommended that healthcare delivery systems become patient-centered, rather than clinician-centered or disease-centered, which is a step in the right direction. In this model they state:

- Patients and caregivers are to be kept informed and involved in medical decision-making.

- Patient care needs to be coordinated and integrated across groups of healthcare providers.

- Healthcare systems need to address the physical and emotional comfort of patients and caregivers and the impact of our treatments on patient and caregiver quality of life.

- Healthcare providers need to have a clear understanding of the patient's concepts of illness and cultural beliefs.

- Healthcare providers need to understand principles of disease prevention and behavioral change appropriate for diverse populations.

Our role, as healthcare providers, is to ensure that the caregiver knows the members of the healthcare team and that they understand our roles. For instance, every time I go into the multidisciplinary clinic in which I work with our patients with ALS, I always go in with the introduction of, “I'm the speech pathologist, my role on the team is to ensure, et cetera, et cetera,” so that every time, they understand who I am and what my role is on the team.

We need to develop a partnership with the patient and the caregiver and keep an open line of communication. We want caregivers to feel as if they can ask us questions if they don't understand the information that we're giving them.

We are to provide written and oral information using plain language. I'll come back to this concept of plain language because there are very specific guidelines that dictate what is considered to be plain language.

CARE Act. The Caregivers Advise, Record and Enable Act has been written into law in at least 36 states and has three components.

- When an individual is admitted to a healthcare facility, they should designate or identify their caregiver. That individual is then entered into the medical record.

- The caregiver must be notified of plans to discharge the patient home or to another facility. We would hope that information would be communicated, but it’s dictated by this act.

- The facility is responsible for providing education on, and demonstration of, any procedures that the caregiver will be expected to perform at home.

Health literacy. The Joint Commission is an entity that many of you are familiar with, and they discuss healthcare literacy in their standards. They state that health literacy issues and ineffective communications place patients at greater risk of preventable adverse events. If the patient does not understand the implications of his or her diagnosis and the importance of prevention and treatment plans, or if they cannot access healthcare services because of communication problems, an untoward event may occur. The same is true if the physician doesn't understand the patient or the cultural context within which the patient is receiving information. They underscore the fundamental right and need for patients to receive information, both orally and written, about their care in a way in which they can understand that information (Joint Commission, 2007).

There is evidence to suggest that how we communicate affects patient/caregiver adherence to our recommendations. We all know that adherence to recommendations is a huge issue. If we're recommending treatment for our patient, and they come back and haven't completed, for instance, dysphagia therapy exercises that we recommended for them, perhaps it's not because they weren't willing to do it, but because they didn't understand what we've been asking them to do.

There is a 19% greater risk of non-adherence among patients whose providers communicate poorly. If I have a patient who says, “I didn't do those exercises that you gave me,” my first thought is, “Did I communicate this effectively? Did you understand what I'm asking you to do?” Getting buy-in from our patients is huge, and if we aren't communicating effectively then we can't expect them to adhere to our recommendations.

In a survey of over 2,000 patients, the majority were unable to recall important elements of medical advice. I have had the experience, as I'm sure many of you have, in which I've completed a swallow study, I have gone over the video of the swallow study with the patient and the caregiver, we've talked about the results, and the caregiver and the patient have expressed their understanding of what we've discussed back to me. They leave my appointment, walk to the physician's clinic for their next appointment with the physician, and when he/she asks, “How did your swallow study go? What did she tell you?” They'll say that I didn't discuss the results with them. In that short span of time in which you feel like you've done a good job as a clinician and conveyed that information, the unfortunate reality is that our patients are taking away very little of the information that we're providing them. So, how can we more effectively enable our patients and caregivers to retain the information that we're giving them?

Healthcare universal precautions. Universal precautions include things like hand-washing, etc within the hospital or healthcare facility. But there is also something called Healthcare Universal Precautions that states that we should assume that all patients and caregivers have difficulty understanding health information. That doesn't mean that we talk down to our patients or assume that our patients are unintelligent, but we do need to assume that when we're communicating to them, they may not be familiar with the terminology that we're providing. They may not understand the information that we're providing them. We need to communicate in ways that anyone can understand.

There's a really nice toolkit available online from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/healthlittoolkit2_3.pdf). The toolkit is available for clinicians who wish to assist caregivers and patients with healthcare literacy.

Plain language. Plain language includes opening our communication with the most important message. You don't want to “bury the lead,” as we say. What's the most important piece of information you want the patient and the caregiver to retain after this training session? Additionally, we need to be concise. We don't want to overwhelm people with information. A good rule of thumb is to limit each communication to four to six key messages. Maybe we provide that orally while we're one-on-one with the patient and the caregiver, but we also may wish to provide that in written communication as well.

We need to speak and write at an eighth-grade level and know what the eighth-grade level is. That’s probably easier said than done. But there are free, online readability calculators that will tell you if the information you are providing is at an eighth-grade level.

We should use bullet points and images. I have found that images are very helpful for our patients. A picture can really drive home what we're talking about. Showing the video of a swallow study to the patient is incredibly helpful as well.

Finally, avoid using jargon and acronyms. I have certainly been guilty of this. We use terms that we think everybody knows. But patients and caregivers don't know those terms and they may be uncomfortable saying, “I don't understand what you're telling me. I don't understand that term that you've just used.” So, we need to avoid, as best we can, using jargon and acronyms.

Assist caregivers in decision-making. We are making recommendations, but at the end of the day, we're asking the caregiver to make an informed decision. Anytime that we're asking somebody to make an informed decision, we have to discuss both the risks and benefits of any treatment that we're discussing. For example, if we are recommending thickening liquids, we need to discuss the potential benefits of thickening the liquids such as a lower incidence of aspiration or they are less likely to develop an upper respiratory infection. But, we also need to discuss the risks such as dehydration because the patient doesn’t like drinking thickened liquids. It is imperative that we discuss the potential risks and benefits of any treatment that we provide and not allow our biases to factor into that. We need to provide accurate representation on both sides of the issue.

It is also our job to know the evidence regarding risks and benefits. Going back to thickened liquids example, there is a lot of information in the literature regarding risks and benefits of thickened liquids. If we're talking about non-oral means of nutrition, it's imperative that we understand the risks and benefits of non-oral means of nutrition. There are a number of articles and resources available to help us provide accurate information regarding risks and benefits of treatment.

We need to allow time for questions. If we have a half-hour session with the patient and the caregiver, and we spend all of our time talking and don't give our patients or caregivers any time for questions, they're probably not going to remember most of what we've said to them.

We need to assess the caregiver's understanding of the information provided. The teach-back method is used to ask patients and caregivers to explain health information in their own words. That needs to be documented. When you're documenting, you need to say that you have had the discussion of risks and benefits of the treatment that you're recommending, and then you need to say that the patient or the caregiver was able to explain that back to you in their own words. Indicate that they understood the information that you provided to them or they were at least able to articulate that information back to you.

Finally, we need to respect the decisions that are made, and support the caregiver and the patient. It's okay if caregivers or patients opt to not follow our recommendations, as long as they're making an informed decision in doing so. We need to respect that decision. However, we are not to abandon the patient if there is still some benefit to us intervening on behalf of the patient. For instance, if we've recommended non-oral means of nutrition, and the caregiver or the patient has decided that they wish to continue a PO diet, are there ways that we can make this patient safer? Are there positioning changes that we could recommend? Are there pacing issues? Are there other things that we could recommend to support this patient and caregiver?

Patient autonomy. The principle of autonomy refers to the patient's right to decide his or her medical treatment and we may not impose medical treatments on a patient. To protect patient autonomy, informed consent must be obtained prior to performing an invasive procedure. I would argue that if you're talking about tube feeding, that's a pretty invasive procedure. Therefore, we need to make sure that patients and caregivers, whoever is providing the informed consent, understand to what they're consenting. They understand the risks and benefits. Additionally, if there are alternatives to a procedure or to treatment, we need to discuss those as well.

Informed consent is not the idea of having a patient or caregiver sign a waiver absolving us of responsibility if the patient or caregiver chooses to not follow the recommendations that we've made. Waivers set up a really bad situation. It can be seen as a form of coercion if you're asking people to sign off on responsibility. It's also setting up an adversarial role between the clinician and the caregiver or patient. Additionally, waivers do not up in court. So, I'm not talking about having somebody sign a waiver. But you do have to document in the medical chart that you've had the discussion and that they understood the information.

Our role is also to make sure information needed for transition to the next level of care is communicated to the caregiver and the patient as well as the healthcare providers. For example, if a patient in an acute care facility is being discharged to a skilled nursing facility, acute rehab, home, etc., we need to ensure that the information needed for that transition is provided to the caregiver and the patient, and to our fellow healthcare providers.

There have been recent questions about whether or not we're allowed to communicate information about the patient's care to other health care providers. This stems from HIPAA concerns and privacy concerns. So, we need to consider how we get information regarding what transpired in acute care to the next level of care.

According to HIPAA, a covered entity may disclose protected health information for the treatment activities of any healthcare provider, including providers who are not covered by the privacy rules. For instance, a primary care provider may send a copy of an individual's medical record to a specialist who needs the information to treat the individual, or a hospital may send a patient's health care instructions to a clinician or a facility to which the patient is transferred. So, when a patient is transferred from the hospital to another facility, we can send information regarding the patient's treatment without additional patient authorization. Ideally, this information should be sent to the next facility. However, we are well aware that oftentimes SLP-specific notes do not get sent. In that case, information can be sent (faxed, if needed) with an indication that the information contained is confidential.

Scenarios

Scenario 1

This is a made-up scenario of a 55-year-old-female involved in a motor vehicle accident, who now presents with significant cognitive and physical issues, including severe dysphagia. She and her husband were both working outside of the home. They have adult children who reside in other states, but they don't have any family who reside nearby. The patient has been healthy, up until the time of her accident. She was perfectly healthy, was involved in an accident and now has significant issues. There's been little utilization of healthcare services prior to this time and the patient did not have an advanced directive.

In this hypothetical situation, a videofluoroscopic swallow study is completed and the patient demonstrated decreased base of tongue retraction, resulting in significant residue within the valleculae after the swallow. We tried a chin tuck, but it didn't improve bolus clearance. Additionally, decreased hyolaryngeal excursion and decreased laryngeal elevation (which is redundant) were noted, resulting in decreased laryngeal vestibule closure during the swallow, and residual material remaining in the pyriform sinuses after the swallow. We had the patient try an effortful swallow and Mendelsohn maneuver, but she was unable to successfully incorporate either one of them. The Mendelsohn maneuver, as you all know, is a very difficult maneuver for patients to execute.

During the study, we also noted aspiration of thin and nectar-thick liquids during the swallow because of decreased airway protection. We noted aspiration of nectar and pudding after the swallow when residue from the pyriform sinuses over spilled the post cricoid space.

In this scenario, how would you explain the results of the swallow study to the caregiver? I'm in an outpatient setting currently, and I understand in acute care settings there are challenges to being able to do this, but I've often found that if we can show a video of the swallow study to the patient and the caregiver, that makes a huge difference in terms of their understanding of what we're talking about.

Would you use terms like “decreased hyolaryngeal excursion” or would you say, “When you swallow, your larynx or your voice box has to move up and forward in order to protect your airway so that things don't go down the wrong tube.” How would you explain that? If you're not in a situation where you can actually go through the video of the swallow study with the patient and the caregiver, can you show pictures or images from the videofluoroscopic exam of that patient? Are there examples that you could provide? Again, I find showing people pictures makes a big difference in terms of their understanding of what we're recommending.

In this case, what would you recommend? This patient's aspirating has pretty significant deficits. She's young. She was healthy before she entered the hospital, but obviously, now we have some challenges. So what would we recommend? The compensatory strategies we tried during the swallow study weren't effective, but would we try active treatment? Would you recommend a non-oral means of nutrition? What is our responsibility in terms of conveying the results? How would we discuss that information with the patient's husband, who is in this case, her healthcare proxy?

Hypothetically, let's say that we've had the discussion of the results with the patient's husband, and he states he doesn't think his wife would wish to have a feeding tube placed. What factors do you think might be affecting his decision? We need to try to understand if the husband has a good understanding of what we're discussing. Does he have a good understanding and he simply doesn't want for his wife to have a feeding tube placed? If he makes a decision that is in contrast to the recommendations we're making, how would we respond to that? Would you ask the husband if he needs additional information? Would you accept that he understands the information, and move on from there? What if the husband says that the husband says he would like for the patient to have the least restrictive diet possible?

In this scenario, does the patient have the right to refuse feeding tube placement? Absolutely. They have the right. The American Medical Association, a President's Commission, and almost every appellate court decision have agreed that artificial nutrition and hydration is a form of medical treatment that can be legally refused. Competent patients, or in this case, competent health care proxies, have the right to refuse tube feedings.

The Institute for Health Quality and Ethics summarizes the American Medical Association's definition of informed consent as more than getting the patient to sign a written consent form because, again, those waivers are not going to absolve us of responsibility and they will not hold up legally. They just set up a really bad scenario for caregiver and healthcare provider, or patient and healthcare provider communication.

Informed consent is a process of communicating between the patient and the provider as well as disclosing and discussing:

- the patient's diagnosis, if known

- the nature and purpose of proposed treatments or procedures,

- risks and benefits of a proposed treatment of procedure

- alternatives that are available

- the risks and benefits of that alternative treatment or procedure

- the risk and benefits of not receiving or undergoing a treatment or procedure

The caregiver and patient should be given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss the recommendation. Patients absolutely have the right to make an informed decision. If they're not capable of making an informed decision, then their healthcare proxy has the right to make an informed decision.

- Autonomy is the ethical principle that states that patients have the right to make their own decisions regarding what medical care they will or will not receive.

- Paternalism is an action performed with the intent of promoting the patient's good but occurring against the patient's will or without the patient’s consent.

Again, oftentimes, we see on some social media platforms where a clinician has made a recommendation and the patient has chosen not to follow that recommendation. Certainly, frustration is expressed because we're making recommendations because we think that's the safest for the patient. When somebody is choosing not to follow that recommendation, we may have difficulty accepting that they understand the decision that they're making.

What implications does this have for the medical team working with the patient? As I said, we need to document, document, document, that we've had the discussion. Also, are there any suggestions that we can provide for reducing the risk of aspiration? The big question, and this certainly came up when I was working in an acute care setting, is what do we do if the patient develops aspiration pneumonia once she has begun an oral diet? We provide appropriate care.

Scenario 2

This is a situation in which the patient is a 77-year-old male who is a quadriplegic due to a remote history of spinal cord injury. He was admitted with a diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, but this is his first admission with pneumonia. Prior to admission, he was consuming nectar-thick liquids and pureed foods. He was tolerating this but said he didn't like the liquids and foods that he was receiving. His wife is his healthcare proxy.

The videofluoroscopic study, in this case, showed reduced hyolaryngeal excursion, reduced laryngeal vestibule closure, silent aspiration of thin and nectar-thick liquids, penetration of honey-thick liquids during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing. Again, how would we explain the results of the study to the patient? Are we going to use terms like “decreased hyolaryngeal excursion” or are we going to use easier to understand terminology? Do people understand what aspiration is and what the implications of aspiration are?

What would our recommendations be? Would you recommend a non-oral means of nutrition? He's done well up to this point, but now he has an aspiration pneumonia. Would you recommend continuing an oral diet?

This patient was able to communicate that he wanted to take thin liquids with regular textures. But again, for whatever reason, he's not the one who is making his healthcare decisions. He states that the altered diet is adversely affecting his quality of life. But the wife states she believes honey-thick liquids will be safest for the patient, and that's what she plans to give him. So, what's our role here? How do we advocate on behalf of the patient?

These are just hypothetical situations, but we need to provide information about risks and benefits of thickening liquids in this situation. We need to provide the information that honey-thick may not be the safest consistency with this patient. We need to consider what the patient's desires are in terms of quality of life.

Scenario 3

This is another situation in which a 75-year-old-male developed significant dysphagia and cognitive impairment following a motor vehicle accident. He was recommended honey-thick liquids and pureed texture foods at an outside facility. He came to see you for a repeat swallow study. His wife is his caregiver and from the beginning she reports that she's very protective of her husband. She explains several times to you that their daughter is an SLP so she is very familiar with dysphagia.

She asks to stay in the room during the swallow study, and then she video records the session, including the swallow study, and the SLP explaining the results of the swallow study. In this situation, how does it make you feel, to be told repeatedly that they have a good understanding of dysphagia. Does that make you feel threatened or are you okay and able to have an informed discussion? This will be an easier discussion because she has an underlying understanding of what you're going to discuss. Would that change your communication style? Would you be more guarded if you know that you're being recorded during your session? What issues might affect the wife's ability to follow your recommendations? All of these questions are things to consider.