Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, SLP in the NICU: An Overview, presented by Anna Manilla MS CCC-SLP, CLC.

It is recommended that you download the course handout to supplement this text format.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the role of the Speech-Language Pathologist in the NICU and the unique considerations of the NICU environment.

- Identify key principles of cue-based and supportive feeding strategies, including side-lying positioning, external pacing, and diet modifications.

- Explain the purpose and application of instrumental assessments in evaluating swallowing in medically fragile infants.

Introduction

I completed my undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, double-majoring in biopsychology, cognition, neuroscience, and linguistics. I did not have the typical speech therapy background in undergrad, coming to the field later in my academic career. Initially on a pre-med track, I pivoted to speech therapy after shadowing a speech therapist in a hospital setting and loving the work—helping people eat and talk, two of my favorite things.

My background in neuroscience and cognition has provided a unique perspective in my training as a speech therapist. I attended graduate school at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and became a certified lactation consultant.

I began my career in outpatient pediatrics within a hospital setting as a generalist, rotating through the general pediatric unit, PICU, cardiac ICU, and NICU, conducting videofluoroscopic swallow studies, and working in outpatient care. Over time, I specialized in the NICU, which has become my favorite unit to work in.

In my current role, I guest lecture at the academic institution affiliated with my hospital, present for ASHA and Feeding Matters, and supervise graduate students. Mentoring is an integral part of my work, and I welcome the opportunity to support future professionals in the field.

NICU Overview

We will start with a general overview of the neonatal intensive care unit.

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit [NICU]

NICUs can be classified into four levels based on the type and complexity of care provided.

Level 1 NICU is considered a well-baby nursery or couplet care and is not typically called a NICU. These units care for healthy babies born at 35 weeks or later, with routine care often provided in the mother’s room. The medical team may include pediatricians, family physicians, and advanced practice providers such as physician assistants or nurse practitioners.

Level 2 NICU offers all the care provided in a level 1 nursery and adds capabilities for short-term breathing support and management of medical issues that are not critical and are expected to resolve within days to weeks. These units often have age and weight criteria, such as babies born at less than 32 weeks and at or above 1500 grams. The medical team may include neonatologists, neonatal hospitalists, and advanced practice providers specializing in neonatal care.

Level 3 NICU provides intensive care for all premature infants and may have specific gestational age requirements. The medical team expands to include neonatologists, pediatric hospitalists, advanced practice providers specializing in neonatology, pediatric medical and surgical subspecialists, and therapists.

Level 4 NICU, also called a tertiary care NICU, offers the highest level of care. These units provide intensive care for all premature infants and those with complex medical problems, often accepting transfers from lower-level facilities. They have pediatric medical and surgical subspecialists available 24/7, along with a team including neonatologists, pediatric hospitalists, advanced practice providers, and therapists. I currently work in a level 4 NICU.

Fetal Development

A significant part of working in the NICU is recognizing how fetal development impacts a baby’s health and care needs. Premature infants often experience complications because they miss critical developmental milestones generally occurring in utero.

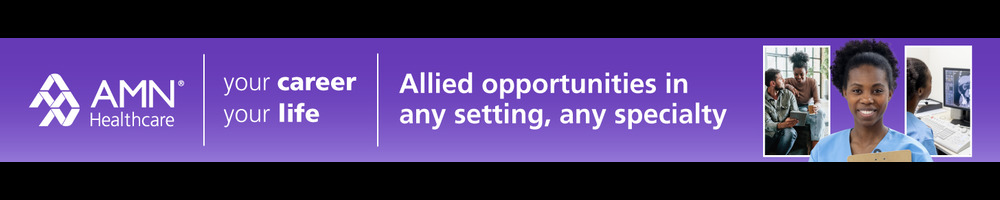

While there are courses dedicated to embryonic and fetal development details, and I do not claim expertise in those areas, I find this chart, in Figure 1, to be a valuable visual tool.

Figure 1. Fetal development chart. (Click here for enlarged image.)

It maps out the timing—by gestational week—when various subsystems develop during the embryonic and fetal phases. This context helps clinicians better understand the challenges faced by infants born at different stages and anticipate the support they may require in the NICU.

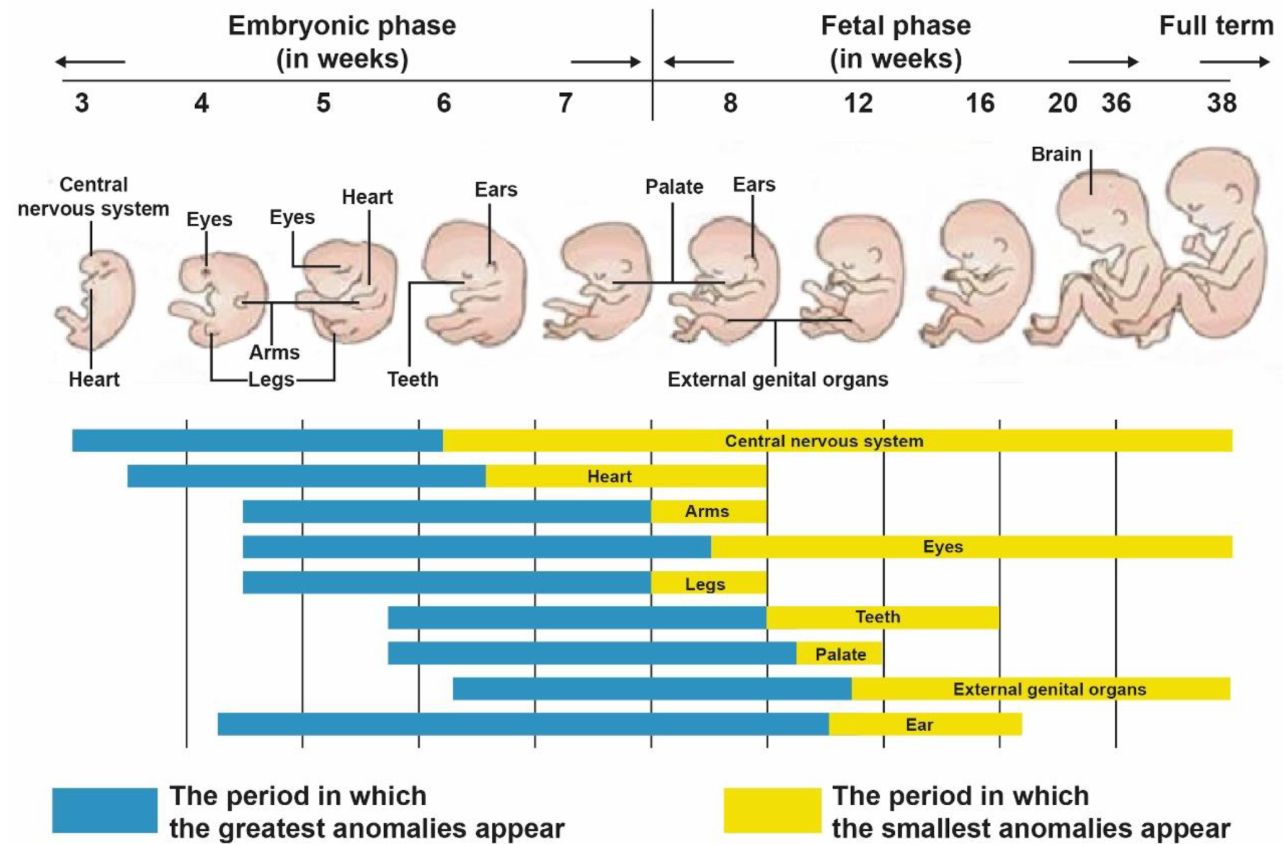

In the NICU, babies are typically born at least 22 weeks' gestation or later, at this end phase of development (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fetal development chart highlighting the last few weeks. (Click here for enlarged image.)

That also means there could have been an anomaly earlier in the baby’s development, affecting specific systems even before birth. In addition, when a baby is born prematurely, some systems do not have the opportunity to finish developing in utero.

Common Diagnoses in the NICU

A big part of NICU practice is recognizing common diagnoses, and I find it helpful to think by body system, just as I do when reviewing a chart. This is not a comprehensive list but reflects frequent conditions we encounter.

Neurologic

Neonatal encephalopathy (HIE), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), neonatal seizures, and hydrocephalus are common diagnoses we see under this category.

Respiratory

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), and pneumothorax. BPD is especially common. It is essentially an iatrogenic NICU problem that can develop after prolonged respiratory support; high levels of support can overdistend alveoli and promote scarring, leading to continued support needs. BPD often resolves by about two years of age, but it significantly affects feeding because breathing is integral to eating, and breathing always comes first.

Cardiac

The heart is complex, and many infants with major defects are treated in dedicated cardiac ICUs. In my NICU, babies with complex cardiac defects are transferred to the cardiac unit. Common diagnoses we still see include atrial septal defect (ASD), coarctation of the aorta, hypoplastic left heart, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and ventricular septal defect (VSD).

Other common conditions: cleft lip and/or palate, genetic syndromes, infant of a diabetic mother (IDM), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and reflux/GERD.

NICU terminology can feel like a second language if you don’t work in this environment daily. I’ll define niche terms up front so we’re on the same page throughout the presentation.

NICU Terminology

In neonatal intensive care, understanding terminology related to age and weight is essential for accurate assessment and communication. Gestational age refers to the interval between the first day of the mother’s last menstrual period and the date of delivery; for instance, an infant born at 22 weeks has a gestational age of 22 weeks at birth. Chronological age denotes the time elapsed since the infant’s actual date of birth, whereas post-menstrual age (PMA) integrates gestational age at birth with the time elapsed postnatally, expressed in days or weeks. Prematurity is classified by gestational age at delivery: infants born between 34 weeks 0 days and 36 weeks 6 days are considered late preterm, those born before 32 weeks are very preterm, and those born before 28 weeks are extremely preterm.

Weight-based classifications provide additional clinical context: infants with a birth weight less than 2,500 grams are categorized as low birth weight (LBW), those under 1,500 grams as very low birth weight (VLBW), and those under 1,000 grams as extremely low birth weight (ELBW). These distinctions are critical for guiding clinical decision-making, anticipating complications, and stratifying risk in neonatal care.

Example

Here’s the example timeline for understanding PMA and corrected age:

Birth: June 1 at 28 weeks' gestational age (in utero for 28 weeks).

August 1: 36 weeks post-menstrual age (28 + 8 weeks since birth).

October 1: 44 weeks post-menstrual age and 1 month corrected age.

Although it has been 4 months since birth, we correct the age for prematurity.

At 44 weeks PMA (4 weeks past full term), developmental expectations are for a 1-month-old.

Correction continues until the child is 2 years old, when most milestones are expected to align with chronological age.

December: 52 weeks PMA and 3 months corrected age.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

One of my favorite things about working in the NICU is the level of interdisciplinary collaboration. Neonatologists, advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapy practitioners, speech-language pathologists, and lactation consultants work closely together. Other essential team members include social workers, respiratory therapists, and music therapists. The NICU is unique in how collaborative it is—each discipline contributes its expertise toward the same goal of achieving the best possible outcomes for the baby.

SLP Scope of Practice [NICU]

In the NICU, the speech-language pathologist’s scope of practice includes evaluating communication, feeding, and swallowing, and providing targeted interventions. Parent and caregiver education and counseling are central to the role, along with staff education and interdisciplinary collaboration. Additional responsibilities may involve quality improvement initiatives, developing and implementing policies, measuring clinical outcomes, applying ASHA’s Code of Ethics, and providing mentorship. While direct patient care is important, much of the impact in the NICU comes from empowering caregivers and equipping the care team with the knowledge and strategies needed to support the infant’s development.

Referral Pathways

Speech therapy involvement in the NICU requires an order or referral from a physician or advanced practice provider before a patient can be seen. Referral pathways can vary by unit. One approach uses automatic order sets in the electronic medical record, such as triggering an order when a baby is born at less than 32 weeks or under 1500 grams. Another pathway is team-identified referrals, where providers request speech therapy if a patient is noted to have difficulties with speech, swallowing, or cognition. A newer model involves automatic therapy consults for all NICU admissions, recognizing that NICU hospitalization is a risk factor for long-term developmental challenges. This model determines therapy frequency based on each patient’s needs.

SLP in the NICU

Let's now look at the role of SLPs in the NICU.

Neuroprotective Care

In the NICU, neuroprotective and neuropromotive care form the foundation of therapeutic practice. This approach is guided by seven core measures: creating a healing environment, partnering with families, positioning and handling, safeguarding sleep, minimizing stress and pain, protecting skin, and optimizing nutrition. Central to these measures is supporting the sensory system—sight, sound, touch, temperature, and light—through intentional environmental modifications that help reduce stress and promote healthy development.

For speech therapy, there are important ways to contribute even when infants are not yet eating by mouth. Babies in the NICU often receive nutrition via NG (nasogastric) or OG (orogastric) tubes or IV lines, but they still benefit from sensory, developmental, and pre-feeding interventions. These might include gentle positive touch, positioning for comfort and stability, oral stimulation to support later feeding skills, and calm sensory experiences that help offset the stress of the NICU environment. The goal is to create positive, regulated interactions that lay the groundwork for safe oral feeding and healthy communication development when the infant is ready.

Non-Nutritive/Pre-Feeding Interventions/Nutritive Interventions/Education

In the NICU, when an infant is not eating by mouth, the focus shifts to non-nutritive or pre-feeding interventions—what many units call non-nutritive therapy. Research supports that non-nutritive sucking (NNS) and orofacial stimulation can indirectly prepare infants for oral feeding while providing positive sensory input. This is especially important because many NICU babies experience repeated negative stimulation around their face from tubes, tape, cannulas, and intubation. These pre-feeding sessions aim to counterbalance those experiences by incorporating gentle, positive touch, supporting self-soothing behaviors like hands-to-mouth, and promoting calm engagement.

A related approach is non-nutritive breastfeeding, in which the parent pumps until the breast is empty and then the baby practices latching with support from the speech or lactation team. Because the breast is already emptied, the infant is unlikely to receive more than small tastes of milk, making it a low-risk opportunity for skin-to-skin contact, bonding, and early feeding skill practice.

Cue-based feeding principles guide both non-nutritive and nutritive interventions. The baby’s signals—whether they indicate readiness, enjoyment, or stress—direct how the session proceeds. Stress cues prompt scaling back, while positive engagement allows continuation. Once oral feeding begins, interventions may include positioning strategies, external pacing, nipple flow modifications, and environmental adjustments to reduce stress.

Education is central to sustainable outcomes. Because therapists may only be present for a small fraction of total feedings, empowering caregivers and training NICU staff ensures consistency. When the entire care team and family apply the same feeding approaches, infants receive steady, supportive experiences that reinforce skill development and promote confidence for caregivers.

What Is Cue-Based Feeding?

Cue-based feeding, sometimes called infant-driven feeding, is an approach where the infant’s behaviors are recognized as meaningful communication that guides the feeding process. Rather than focusing solely on how much milk the baby consumes, the emphasis shifts toward skill development, co-regulation with the caregiver, and protecting the overall feeding experience.

This model prioritizes quality over quantity. The goal is to ensure that feeding remains a positive, stress-free experience, even if the intake volume is lower in the short term. This represents a significant cultural shift in NICU care over the past 10–15 years, moving away from the historical “high volume at all costs” mentality toward a research-supported, infant-led process.

Implementation requires ongoing education and modeling for staff, new hires, and families. Since infants cannot speak but communicate through cues, the therapist teaches caregivers how to interpret and respond to those signals—recognizing readiness, pacing needs, or signs of stress—to make each feeding session supportive and developmentally appropriate.

Infant Communication

Babies communicate comfort or distress through movements, facial expressions, posture, and physiologic changes.

Signs of stress can include frantic, jerky movements; stiff arms or legs with extension; crying; the “preemie stop hand” (fingers splayed with the hand in front of the face or mouth); averting gaze; wrinkled brows; yawning, hiccups, or sneezing in premature infants; and changes in vital signs such as oxygen desaturation, decreased heart rate, or increased respiratory rate.

Signs of contentment often include a calm, steady heart rate and breathing; a relaxed body posture; hands near the face; smiling or cooing in older infants; minimal, smooth movements; a relaxed facial expression; sucking on hands or bringing hands to the mouth; and relaxed, even eye-opening, with steady eye contact from older babies.

Cue-Based Feeding and Communication

Cue-based feeding is an ongoing feedback loop in which I continually read and interpret the infant’s cues and adjust support accordingly. It works like a conversation: the infant “speaks” through behavioral and physiologic cues, and I respond by adding, removing, or modifying supports such as environmental adjustments, positioning, or pacing. I then reassess the infant’s response and adapt again. This cycle repeats throughout the feeding to keep care infant-driven and responsive in real time.

Tools to Support Cue-Based Feeding

Tools I use to support cue-based feeding include environmental modifications, positioning, external pacing, adjusting nipple flow rates, and modifying liquid thickness. Each of these strategies plays a role in creating safe, effective, and positive feeding experiences, though listing them all at once sometimes feels like its own coordination exercise.

[Typical] Order of Implementation

I start with environmental modifications to make the environment less stressful and more supportive for the baby. Next, I adjust the nipple flow rate before proceeding to positional modifications, external pacing, or thickening. Nipple changes are uniform and consistent across providers—you simply switch the nipple on the bottle. The third step is positioning, focusing on horizontal milk flow, which means using upright or side-lying positions to support coordination. Then comes external pacing. If needed, the final adjustment is thickening liquids or diet modification.

Developmentally Supportive Environment

To create a developmentally supportive environment, I return to the core measures of neuroprotective care and focus on the sensory system, especially light, sound, and touch.

For light, I keep in mind that less than 2% of external light reaches a baby in utero. My goal is to balance dimmed ambient light, natural light, and brighter task lighting when needed. Continuous bright light can disrupt sleep–wake cycles, so I may shield the baby’s eyes during nursing assessments to reduce stress. I dim the lights once it’s time to feed to create a calmer atmosphere.

For sound, I remember that while sound is part of normal fetal development, in utero, it’s muffled and low-frequency. Premature infants are more vulnerable to physiologic instability from noise. So, I model a quiet environment—soft voices during feeds, limiting casual conversations, and closing the door partway when possible to minimize background noise.

I use gentle, slow, modulated movements and avoid sudden motions for touch. Light touch can alert preterm infants, while static touch is calming. In utero, babies experience constant 360-degree surface pressure, or containment, which promotes security and reduces stress. I replicate that through swaddling during feeds and using my hands to provide containment when the baby is unswaddled for care, such as placing one hand over their arms and another near their head during a diaper change to create a boundary and help them stay regulated.

Nipple Flow Rate

Nipple flow rate is the speed at which milk moves through the nipple into the infant’s mouth. During feeding, babies coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing, with each swallow requiring them to pause their breathing for about one second. This pause happens frequently throughout the feed, creating a significant respiratory load, especially for infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or other baseline respiratory illnesses.

A higher flow rate means the infant must swallow more often, leading to more frequent breathing interruptions. Over time, this can result in fatigue, stress, disengagement, or even compromised airway safety if the infant can’t keep pace with the milk flow. While healthy full-term infants may be able to adapt by altering their sucking pattern, preterm infants are less capable of making these adjustments.

A slower flow rate reduces the frequency of swallows, providing more time for the infant to coordinate the suck-swallow-breathe sequence and maintain physiologic stability. It can also promote stronger oral musculature development, which benefits later feeding and speech skills.

Although adjusting flow rate isn’t a solution for every feeding difficulty, it’s a valuable and often underutilized strategy. Slowing the flow may seem counterintuitive to slow the flow when a baby is struggling to take in enough volume, but this adjustment can make feeding less stressful and more sustainable.

Brito’s 2014 research highlights just how much flow rates vary between bottle brands—even when labeled similarly (e.g., “Level 1” or “slow flow”). In her findings, nipples labeled the same across brands could have significantly different flow speeds. This underscores the need for providers to guide families in navigating bottle choices. While her 2014 chart offers a visual example of this variability, updated data can be found on Britt Pitos’ Infant Feeding Lab website, which I regularly use in practice.

Positioning

I most often use two primary positions to support infants during feeding: side-lying with horizontal milk flow and upright with horizontal milk flow.

In side-lying, the infant rests on their side with hips and shoulders stacked and the head in line with the body. The bottle is held parallel to the floor. This is similar to how many breastfeeding positions—such as cross-body, cradle, or football—naturally position the baby.

The upright position is essentially a rotated version of side-lying: the infant sits upright while the bottle remains horizontal and parallel to the floor. In both positions, the infant draws milk from the bottle rather than relying on gravity to deliver it, as in a reclined cradle hold with an inverted bottle.

McGrath’s 2023 study found that the same bottle, when inverted, allowed milk to flow four times faster than when it was held horizontally. This difference is due to hydrostatic pressure and changes in the bottle’s internal air pressure. Understanding this science reinforces why side-lying and upright horizontal positions help maintain a more manageable flow rate, allowing the infant greater control over sucking, swallowing, and breathing.

If you want a deeper look into the physics behind this, McGrath’s article offers a clear explanation of the bottle dynamics at play.

External Pacing

External pacing helps infants take intentional pauses during feeding to catch their breath. Feeding requires the coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing, and breathing is typically the last function to integrate fully into that suck–swallow–breathe sequence. This usually occurs around 34–37 weeks postmenstrual age, but it can be delayed or disrupted by medical history, respiratory conditions, or overall endurance.

To pace externally, I either tip the bottle downward so milk drains out of the nipple while keeping it in the infant’s mouth or—if needed—completely remove the nipple from the mouth. Both methods cue the infant to pause and breathe without continuing to swallow.

An immature suck–swallow–breathe sequence might present as multiple consecutive sucks and swallows without any breaths, followed by rapid “catch-up” breathing. For example, the pattern could look like suck–swallow, suck–swallow, suck–swallow… pause… breathe, breathe, breathe. With pacing, the goal is to gradually shape this into a more integrated rhythm, such as suck–swallow–breathe, suck–swallow–breathe, allowing for safer, more efficient feeding and better physiologic stability.

Thickening Liquids

Thickening liquids in the NICU is a complex and often debated intervention, and I always recommend an instrumental swallowing assessment before making any diet modification.

For dysphagia, thickening can increase bolus viscosity, which helps the bolus hold together more cohesively in the mouth. This can improve oral motor control, slow bolus transit from the oropharynx into the esophagus, and allow for better coordination of swallowing and breathing. By moving more slowly, the bolus can provide increased time for airway protection and may reduce penetration or aspiration events.

For gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), thickening can help when reflux affects feeding. GER is the normal passage of gastric contents into the esophagus; it becomes GERD when it causes distress, poor weight gain, or airway symptoms. Because reflux in infants is often non-acidic, acid-suppressing medications may not be fully effective. Thickening feeds has been shown in multiple studies to reduce the number of regurgitation episodes. By increasing viscosity, thickeners can reduce how far refluxate travels toward the oropharynx, which may lower the risk of penetration or aspiration from reflux events.

When thickening is used, it should follow a collaborative decision with the medical team, guided by objective assessment and tailored to the infant’s needs.

Types of Thickeners

The type of thickener used in the NICU is highly unit-dependent and often dictated by neonatology approval. When I conducted an informal survey of NICU practice patterns across the United States last year, the responses varied widely. The most common options reported were oatmeal, rice cereal, and GelMix, though many NICUs shared that no thickener use was permitted.

For the NICU population, the primary thickening options are:

Rice cereal

Oatmeal

GelMix (the only commercial thickener currently approved for breast milk)

Some NICUs, particularly in recent research discussions, have explored food purees for thickening, though my unit does not currently use them. Commercial thickeners—like SimplyThick, Thick-It, or Purathick—are more common in older pediatric populations and are not routinely used with neonates due to safety and developmental considerations.

GelMix deserves special mention: it is the only commercially available thickener that works with breast milk, but it has strict parameters. It can only be used for infants over 42 weeks corrected age and weighing more than 6 pounds. For families who have worked hard to provide breast milk, this option allows the infant to remain on breast milk while still meeting their swallowing safety needs.

In terms of clinical decision-making for infants under one year:

Breast milk, <42 weeks corrected: No safe thickening options. External supports (nipple flow rate adjustment, pacing, positioning) and possibly supplemental NG feeds are the only interventions.

Breast milk, ≥42 weeks corrected: GelMix is the only option for thickening.

Formula-fed, no added calories needed: GelMix can be used.

Formula-fed, added calories needed: Cereal (rice or oatmeal), purees, or yogurt may be considered if the medical team approves.

All thickening decisions must be individualized, medically cleared, and supported by a multidisciplinary approach.

Instrumental Evaluations of Swallow Safety and Function

Next, we will talk about instrumental evaluations of swallow safety and function. So swallow studies and FEES, or VFSS and FEES. I call them swallow studies. I know different places of work have different names for them.

Instrumental Assessments [VFSS and FEES]

VFSS

First, I will cover video fluoroscopic swallow studies (VFSS), or a swallow study. Advantages include assessing the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallowing, screening the esophagus for issues like reflux (though it’s not diagnostic for esophageal disorders), and visualizing the airway before, during, and after the swallow.

Disadvantages include radiation exposure, a limited exam duration due to radiation limits, and the requirement for the infant to leave their hospital room, which can be challenging if they have multiple lines or high respiratory support. VFSS can also be less sensitive to microaspiration, and events may be missed due to fluoroscopy's on/off nature.

During VFSS, the goal is for liquid to move efficiently through the esophagus toward the stomach rather than entering the airway. In some cases, bolus spillage into the piriform sinuses may occur before the swallow is triggered, which can highlight swallowing inefficiencies and provide important information about the infant’s anatomy and physiology.

FEES

Next is the flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), which is performed in the NICU in collaboration with the ENT. Unlike adult FEES, where SLPs often scope independently, pediatric FEES is typically scoped by the ENT while the SLP manages feeding, interprets findings, and creates the feeding plan.

Advantages of FEES include direct visualization of mucosal structures and vocal cords, no time limit once the scope is in place, bedside portability, and the ability to assess secretion management. Disadvantages include the whiteout period during each swallow—significant in infants who swallow frequently—which can make interpretation challenging. FEES does not assess the oral phase, cannot screen the esophagus, and may cause mild discomfort, although skilled ENT colleagues can significantly minimize this.

During FEES, structures such as the epiglottis, arytenoids, and vocal cords can be directly visualized. Variability in appearance may occur depending on the infant’s activity at the time of assessment—for example, crying can alter the shape of the epiglottis and result in adduction of the vocal cord

Parent Education & Empowerment

Many NICUs are moving toward the goal of beginning neuroprotective and neuropromotive care as soon as possible after admission, with early involvement of ancillary services—speech, OT, PT, child life—to focus on caregiver education and participation. From the earliest days of the infant’s NICU stay, parents should be introduced to the principles of neuroprotective care and shown how to provide supportive interventions, such as positioning, pre-feeding strategies, and techniques like “four-hand care,” where one person offers containment while another performs care.

The aim is to empower parents to be active partners in their infant’s developmental progress, equipping them with the skills and confidence to contribute meaningfully. While the medical team’s initial focus is on stabilizing the infant, ancillary providers can bridge the gap by ensuring parents know how to connect with and support their baby in ways that promote bonding and neurodevelopment.

Parent Education & Empowerment

The goal is to help parents engage with their baby from the beginning in ways that support both the infant and the caregiver, fostering confidence and a sense of connection. We want parents to feel like parents, even in an environment that can feel anything but natural. Telling a parent, “Don’t touch your baby—they’re too sick,” can be discouraging, especially when they then watch a medical provider open the isolette and touch their child. The message instead should be, “Here’s how you can interact with your baby safely and supportively.” By guiding parents toward positive, developmentally appropriate interactions, we empower them to be active, confident participants in their baby’s care.

Parent-Centered Bonding Activities

Parent-centered bonding activities can be adapted to the infant’s medical stability, and in most cases, there is something meaningful that parents can do throughout admission. These activities might include skin-to-skin contact, talking, singing, or reading to the baby. Positive touch and containment holds can be incorporated into care routines. Scent exchange is another option—parents can wear a scent cloth inside their clothing, allowing it to absorb their scent, which is then placed in the baby’s crib or with the baby. Visual bonding through eye contact, involvement in feeding, and personalizing the infant’s space also helps foster connection.

Empathy is central to our work as speech therapists. While essential in all settings, it is particularly vital in the NICU and pediatric environments. This experience is stressful for both infants and their parents. Having a sick baby, not being able to bring them home, and struggling to feel like a parent can be overwhelming. Many families may not be functioning at what they consider their “best,” but they are giving 100% in the context of their situation. Recognizing and honoring that reality helps us provide the compassionate, family-centered care that supports the infant and their parents.

Empathy

Giving everyone the benefit of the doubt, approaching with extra empathy, and being willing to listen truly go a long way. Parents have described the NICU experience in powerful terms:

“Having a baby in the NICU is an intense experience that hits you like a giant slap in the face. It waits for you to shake it off and then drop-kicks you in the stomach. Not only are you heartbroken and terrified and desperate to see your baby grow and develop and eventually be discharged, but you are also constantly on the verge of losing your mind completely from the stress and exhaustion and worry and all the emotional ups and downs.”

Another parent shared, “Delivering your baby is hard, but not being able to hold your baby after is even harder.”

I work to convey to parents the following messages: You are a parent, not just a medical decision-maker. You are not a bad parent. You are a good parent.

For team members, it helps to start from the baseline that everyone is doing their best and has the patient’s best interests at heart. Disagreements about care approaches are normal, especially in the interdisciplinary and highly collaborative NICU environment. This collaboration is a strength, but it can also require careful navigation when perspectives differ. Functioning from a place of mutual respect and shared goals makes these conversations more productive.

For ourselves, the NICU can be emotionally demanding. We see very sick infants, participate in goals-of-care and end-of-life discussions, and often deliver difficult news about feeding safety or the need for supplemental nutrition via G-tube or NG tube. Sometimes, long-term feeding prognoses are poor. These are hard conversations to have, and they take a toll. It’s important to recognize when you need to step back, take a break, and seek support from coworkers, mentors, or peers. Self-care is essential for sustaining the emotional energy this work requires.

Discharge Planning

I approach parent education and empowerment in the NICU with discharge planning in mind from the very beginning, not just in the final days before a baby goes home. My goal is for families to feel confident in supporting their baby’s feeding well before discharge. I want parents to understand cue-based feeding, how to recognize and respond to their baby’s needs, and how to provide appropriate supports for their baby to be comfortable and capable once they transition home.

While I can prepare families early, there are factors I can’t fully control in the discharge process. Education still needs to include clear homegoing recommendations and information on community resources. I often provide letters of medical necessity when required, especially for thickeners such as GelMix. In our unit, we’ve successfully worked with DME (Durable Medical Equipment) companies to get GelMix covered by insurance for infants with documented needs based on swallow study results.

Referrals to early intervention services are another critical step. In Illinois, we call this CFC, and many NICU graduates qualify for services from birth to three years. I make sure families understand the process and what supports are available.

The criteria for outpatient therapy vary by setting. In my hospital, infants going home with supplemental nutrition (NG or G-tube) and/or on thickened liquids with a history of aspiration automatically qualify for outpatient follow-up. I ensure appointments are scheduled at a time that works for the family and within an appropriate time frame after discharge.

Finally, many hospitals have NICU follow-up clinics where therapists help staff with visits and conduct developmental assessments. These clinics follow children for several years post-discharge to monitor progress and address emerging needs. Ensuring a seamless transition to these services is part of my role in supporting the infant’s development and the family’s confidence at home.

Last Thoughts

This work is such a privilege. I love what I do, and I’m grateful daily for the opportunity to work with these babies, their families, and the incredible team around them. The NICU is challenging—sometimes in ways that are hard to put into words—but that’s also what makes it meaningful.

I’m constantly learning in this role. I’ll admit, I often experience impostor syndrome, especially with the depth of mentorship and expertise I’m surrounded by. But that’s also what drives me to keep growing. Working with graduate students is one of my favorite parts of the job—they bring fresh perspectives, new research, and ideas that keep me sharp and current.

My reminder to myself and to all of us is to always be students. Stay curious. Keep learning. Never forget the privilege of doing this work.

Questions and Answers

Is corrected age the same as adjusted age?

Yes. They are the same concept—just different wording. This is the calculation I use when a baby is preterm, for example, when determining eligibility for early start services.

Since the breast is never empty, what is the level of risk for aspiration during non-nutritive suckling at the breast?

There’s no single “exact” risk number. When an infant is cleared for non-nutritive suckling, the medical team makes the decision based on the baby’s overall medical picture and stability. We typically avoid it when a baby is on higher respiratory support like CPAP. Babies usually need to be on high-flow or low-flow nasal cannulas to access the breast for a functional latch. The decision is made collaboratively between the medical team, parents, and the therapist.

Are you the only SLP in your NICU?

I was at first, but now we have two full-time SLPs training a third. Our census has grown, and while our Level IV NICU is smaller than some (about 60 beds), we’ve expanded our therapy team to meet needs.

I’m in San Diego and know a family with a 23-weeker who only has OT for feeding in the NICU. Is that common?

Yes—in some regions, especially on the West Coast, OTPs often address feeding in the NICU. In the Midwest, where I’ve worked, SLPs typically handle dysphagia. Practice patterns vary; OTPs and SLPs share feeding responsibilities in some hospitals.

How might you approach advocating for SLP involvement in a NICU with only OT?

Emphasize that SLPs add another lens rather than replace what’s already being done. We share many neuroprotective and neuropromotive interventions—like containment, skin-to-skin, and cue-based care—but approach them from different angles. The focus should be on collaboration, learning from each other, and enhancing care, not territory.

In adults, NG tubes are temporary. Is it the same for NICU babies?

No. In adults, NG tubes are often short-term before transitioning to a PEG. In the NICU, NG tubes can be used longer term, and some babies may go home with them. In our unit, babies must meet specific criteria to be discharged home with an NG tube; otherwise, they get a G-tube. This is more common in NICUs than in adult care.

Recommendations for an SLP who wants to become a Certified Lactation Consultant?

Do it—it gives you a valuable perspective on breastfeeding. Lactation consultant training focuses heavily on the maternal side: milk production, supply, and management. Pairing that with your SLP knowledge of infant swallowing mechanics gives you a well-rounded skill set to support feeding goals and collaborate effectively with lactation teams.

References

Please refer to the handout.

Citation

Manilla, A. (2025). Audiology essentials for non-audiologists, presented in partnership with RIT/NTID. Continued.com - SpeechPathology.com, Article 20752. Available at https://www.speechpathology.com/.