Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Medically Complex Decision-Making for the SLP, presented by George Barnes, MS, CCC-SLP.

It is recommended that you download the course handout to supplement this text format.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify common errors in clinical decision-making

- Describe at least two ways to prevent and/or minimize the impact of mistakes

- Describe at least two practical scenarios in which direct approaches to clinical decision-making can be implemented immediately

Introduction

Thank you to everyone who took time out of your busy schedules to invest in learning and advancing your education in this field. Continuous growth is vital for all of us, and your commitment is truly appreciated. Let’s dive in and explore these critical aspects together. This short course focuses on improving our ability to make effective decisions, particularly when caring for patients with high levels of medical complexity. To help us understand the patient experience, I invite you to close your eyes, if you are comfortable, and imagine this scenario:

You have just been admitted to the hospital. You feel slightly dizzy and uncertain about what is happening. A series of tests have been conducted, and now you are being admitted to the floor. you are in a patient room, lying in bed. Suddenly, someone approaches your bedside and informs you that they will be conducting a swallowing evaluation

You are not quite sure what that means, but you follow their directions. It is now been eight or nine hours since you have had anything to eat or drink. You are asked to chew a cracker as fast as you can and swallow it, which you do. But since your mouth is so dry, some pieces fall apart, fall out of your mouth, and are left over.

They then give you something to drink, instructing you to consume it all at once, and it is a fair amount of liquid. As you are doing that, you clear your throat a little bit. The next thing you know, you are receiving food that does not quite look like food. It is presented in mounds on your plate, and the liquid is so thick you have to drink it with a spoon. This is the reality that many of our patients are swept into without really knowing what is going on or why they need to be eating and drinking these things.

Often, reevaluations do not occur for extended periods—sometimes days, sometimes weeks. You can imagine being stuck on this type of diet; someone might not want to eat or drink as much, leading to malnutrition and dehydration. The person may become weaker over time, again, not fully understanding why they are doing this in the first place.

Let's step back from that situation and return to our roles as speech pathologists, as clinicians responsible for these patients. By shifting our perspective slightly, we can glimpse what life might look like on the other side for a few minutes. This presentation is not about finger-pointing or declaring that our past practices are entirely wrong and this new approach is entirely right. Instead, it is about figuring it out together. A significant part of this is the decision-making process, where we identify what is most important, determine the problem we are trying to solve, and explore various approaches and strategies. By laying out information and alternatives, we aim to arrive at the best decisions, leading to effective interventions and, ultimately, the most effective care for our patients.

Our agenda includes a brief introduction to the art of decision-making and how our rationality can sometimes lead us astray. we will then delve into recognizing errors by examining patterns of thinking, cognitive biases, and heuristics that we often fall victim to. We will identify common mistakes that occur repeatedly and discuss what to look out for to prevent them in the future. Finally, we will explore strategies to minimize these errors, culminating in a case study that puts some of these strategies into practice.

This case involves a real patient with whom I applied these strategies and found them effective. You will see the theories come to life, so to speak. I will keep this brief. I spend most of my time working clinically in a critical illness recovery hospital and acute care settings. Recently, I have been dedicating more time to behind-the-scenes activities such as education and mentorship. I also run a mobile FEES (Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing) company and strive to write as much as I can. My passion for cooking and eating has naturally led me to this career, as I am dedicated to helping others enjoy these simple yet profound pleasures.

You might wonder why I am discussing decision-making. I am not a guru in this area, but over the past few years, I have systematically studied my own decisions, as many of you have. I have delved into research and science to understand what constitutes an effective decision. How do we organize the vast amount of information before us to do what is best for the patient? Working in long-term acute care (LTACH) and critical illness recovery has compelled me to approach my decisions more scientifically. I noticed I was repeating the same actions with my patients without truly assessing their effectiveness.

This introspection led me to scrutinize my own decision-making processes, aiming to identify changes that could enhance patient outcomes. Each patient presented a lengthy list of diagnoses, encompassing pages of medical history, various conditions, and surgical interventions—all factors requiring careful consideration. Managing multiple patients daily in such a complex, high-stakes environment compelled me to reflect internally and determine how I could improve my approach.

The Stakes Are High

- Biases exist in healthcare (Featherston et al., 2020)

- Cognitive biases existed in 77% of studies (Saposnik et al., 2016)

- Medical errors account for close to 10,000 deaths each year (Kohn et al., 2009)

Biases exist everywhere. Cognitive biases are patterns of thinking—mental shortcuts, essentially. We use them constantly. It is why it is so easy to know what we are going to do in the morning when we wake up. We have habits: we immediately brush our teeth; we immediately know what we are having for breakfast.

When we are driving, we instinctively know when to stop, go, or turn. These habits are beneficial; they conserve mental energy for more complex decisions. However, cognitive biases—these mental shortcuts—can still influence us when working with complex patients and sorting through intricate information. For instance, a systematic literature review found that cognitive biases were present in 36.5% to 77% of diagnostic case scenarios analyzed.

Essentially, the majority—more than three out of four—of the studies exhibited some level of cognitive bias in healthcare decisions. These decisions are significant; errors can profoundly impact people's lives. For instance, a study by Johns Hopkins Medicine suggests that medical errors may account for over 250,000 deaths annually in the U.S., positioning them as the third leading cause of death, following heart disease and cancer.

That is an extraordinary number—comparable to a Boeing 747 crashing every day. Even if we can only make small improvements, it is crucial to recognize and correct these errors to prevent them from recurring. While we cannot eliminate them completely, we can strive to reduce their frequency moving forward. We are all evolving, and one of the most important takeaways from this presentation is the need to identify our current mistakes. Failing to do so means we will continue making the same errors, neglecting to adopt new approaches, interventions, and strategies.

Recognizing errors when they occur is crucial for our growth and the advancement of patient care. I will be the first to admit that I make mistakes quite frequently. it is not about completely eliminating errors—that's unrealistic. Instead, it is about acknowledging them and striving for improvement. For instance, I once worked with a patient for six weeks, aiming to transition him from thickened liquids and pureed foods to a regular diet. This involved countless hours of therapy, including compensatory strategies and pharyngeal strengthening exercises. Despite our extensive efforts, the desired progress was not achieved, prompting me to reevaluate my approach and learn from the experience.

We conducted a modified barium swallow study on the first day and repeated it six weeks later. The results were promising; the patient showed significant improvement, allowing a transition to a regular diet. Eager to share the good news, I entered his room, only to find him still consuming pureed food and thickened liquids.

I told him, "You do not have to eat that anymore. Great news—you can eat whatever you want now; you can have a regular diet." He replied, "Oh, yeah, that is great. I appreciate your time, but I actually prefer to eat the puréed food. It is easier on my teeth, and the thickened liquids remind me of a drink I used to have back home. If you do not mind, I would like to stick to this diet." In this instance, I completely missed what was most important. As you will see when I discuss the decision-making process, identifying patient preferences is step number one.

Identifying the problem is paramount. We must determine what is most important and where our focus should lie. I missed this with that patient, but recognizing such mistakes is essential for improvement.

Recognize Errors

Dysphagia management often involves making predictions about how today's decisions will affect patients in the coming days or weeks. But how effective are we at making these predictions? Studies have shown that expert predictions can be as unreliable as random guesses. For instance, research by psychologist Philip Tetlock revealed that experts' forecasts were no more accurate than those made by chance.

We are not very good at making decisions, nor at predicting their outcomes. For instance, studies have shown that when people claim to be 90% certain, they are correct only about 75% of the time. This overconfidence can lead us to be wrong more often than we realize. I know this has happened to you before, and I know it is happened to me. you are so sure you are right about something—you would argue to the end just to prove it—only to find out that you were completely wrong, completely off base. At the moment, it is really difficult to tell that. But we have to recognize that we are human; we make mistakes.

Bad Things Happen

- But When?

- During unfamiliar circumstances or when short on time and feeling rushed

When do mistakes happen? Research indicates that the most common errors occur during unfamiliar circumstances or when we are short on time and feeling rushed. It would be ideal if all our situations were familiar and we never felt pressed for time—problem solved. However, the reality is quite the opposite. Our daily routines are filled with unfamiliar circumstances, surprises, complex patients, and conditions we may not fully understand. This is not just in speech pathology but in healthcare in general. It is rare to encounter a patient and know exactly what to do. The human body is one of the most complex entities in the known universe.

Medical care is inherently complex, and mistakes are inevitable. Recognizing this, it is important to be aware of situations where errors are more likely. For instance, if you are working on a PRN basis, moving between different facilities, or managing a caseload of 12 patients with a tight schedule, these are times when you are more prone to errors. Being mindful of these circumstances allows you to take proactive steps—such as seeking assistance or adjusting your workload—to mitigate potential mistakes.

Biases and Heuristics

- Availability Heuristic

- Speaking of dysphagia…

- Confirmation Bias

- I won’t stop looking for dysphagia until I find it.

- Anchoring

- Dysphagia must be the cause of everything

- Base Rate Neglect

- is not every pneumonia aspiration-related?

Now, let's discuss some common cognitive biases and heuristics that can influence our decision-making. Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that can sometimes lead us astray. One example is anchoring bias, where we rely too heavily on the first piece of information we receive. For instance, if we walk into a room and observe a patient coughing during their initial trial, we might fixate on that observation, allowing it to unduly influence our subsequent assessments.

We might automatically think this person has dysphagia, and every subsequent trial we observe is influenced by that initial information. In contrast, consider someone who performs perfectly—no issues, no coughing, no throat clearing, no signs of aspiration, no oral motor deficits—throughout the entire clinical assessment.

However, at the very end, just as you are about to leave, the patient coughs. You might think, "They have been fine the entire time; it is probably nothing." In both scenarios, the patients coughed once, but our initial observations can disproportionately influence our overall assessment. This exemplifies how anchoring bias can affect clinical decision-making.

This exemplifies confirmation bias, where we focus on information that supports our initial assumptions. For instance, during a chart review, noticing right lower lobe pneumonia might lead us to immediately suspect dysphagia-related aspiration pneumonia. Consequently, every time the patient coughs or clears their throat, we interpret it as evidence of aspiration. However, the situation is often more complex, and such premature conclusions can lead to diagnostic errors.

Diagnosing pneumonia is more complex than it may seem. Base rate neglect is another cognitive bias to consider. This occurs when we overemphasize individual characteristics and underemphasize statistical base rates—the general prevalence of a condition within a population. In other words, we might focus too much on specific details and overlook broader statistical information.

Consider a patient admitted with a general pneumonia diagnosis. We might wonder about the likelihood of this being aspiration-related pneumonia. Base rate neglect can lead us to overemphasize individual characteristics and underemphasize statistical base rates. For example, "Is this really aspiration pneumonia?" For instance, among patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, aspiration events cause pneumonia in approximately 5% of those under 80 years old and 10% of those aged 80 and above.

If we do not consider statistical base rates, we might estimate that 30%, 40%, or even 50% of patients admitted with pneumonia have aspiration pneumonia. However, statistics indicate that the prevalence can be as low as 5%. This means that nearly 95% of patients with a pulmonary infection may not have aspiration pneumonia. Being aware of these base rates can help us avoid overestimating the likelihood of aspiration pneumonia and guide more accurate diagnoses.

We are all susceptible to biases and heuristics. The goal is not to eliminate them entirely—an impossible task—but to recognize when and how they occur so we can address them effectively. To achieve this, we will explore a decision-making process designed to mitigate these cognitive pitfalls.

Minimize Errors

Let's take a moment to reflect on our thinking processes—a metacognitive exercise, if you will. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman describes two modes of thought: System 1 and System 2.

- System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive. It operates with little to no effort and often relies on heuristics—mental shortcuts that allow us to make quick judgments. For example, when deciding what to eat or wear in the morning or when driving a familiar route, we are engaging System 1 thinking. This system is efficient for routine decisions but can lead to errors when applied to complex situations.

- System 2, on the other hand, is slow, deliberate, and analytical. It is activated when we encounter novel situations or complex problems that require careful consideration. For instance, solving a complex math problem, planning a detailed project, or making significant life decisions like buying a home involves System 2 thinking. This system requires more cognitive resources and is less prone to biases, making it more suitable for complex decision-making.

In the context of healthcare, both systems play crucial roles. Experienced clinicians often rely on System 1 thinking to make quick decisions based on pattern recognition and experience—a process sometimes referred to as "intuition." However, this can lead to cognitive biases if not checked. For example, a clinician might diagnose a common condition based on initial symptoms without considering less common alternatives—a bias known as "anchoring."

Conversely, System 2 thinking is essential when dealing with complex or unfamiliar cases. It allows clinicians to methodically analyze patient information, consider differential diagnoses, and weigh the risks and benefits of various treatment options. Engaging System 2 reduces the likelihood of diagnostic errors and enhances patient care.

Understanding when to engage each system is vital. While System 1 allows for efficiency, especially in high-pressure environments, it is important to recognize situations that require the more deliberate approach of System 2. By being mindful of our cognitive processes, we can improve our decision-making and provide better outcomes for our patients.

System 1 thinking can be highly beneficial, especially for experienced clinicians like speech pathologists who have accumulated extensive knowledge over many years. When you have spent decades in the field, encountering similar patient cases and making consistent decisions, your instincts—shaped by biases and heuristics developed over time—become valuable tools. These habits and reflexive thought processes are advantageous when:

Extensive Experience: you have repeatedly encountered similar situations, allowing for quick, intuitive judgments.

Timely Feedback: You receive prompt feedback on your decisions, enabling you to assess outcomes and refine your approach.

Humility and Adaptability: You possess the humility to acknowledge mistakes and adjust your processes to prevent future errors.

By fulfilling these conditions, System 1 thinking allows for efficient and effective decision-making in familiar scenarios. However, it is crucial to remain vigilant and recognize when a situation deviates from the norm, necessitating a more deliberate, analytical approach.

Decision-Making in 6 Steps

Here is the decision-making process I want to introduce. Remember, this is not a perfect solution or something you absolutely need to adopt. The goal of this talk is to encourage you and your team to develop a process that works for your specific needs. It is not about using this particular method—it is about having a structured approach that allows you to step back and engage in System 2 thinking.

Unless you have been practicing for decades, making similar decisions repeatedly, receiving regular and accurate feedback, and refining your approach with humility, most of us will benefit from implementing some form of structured process. While I initially said “strict,” I realize that is not the right word. It does not have to be rigid. Instead, it should be a formal yet flexible decision-making framework you can rely on for those particularly complex cases where the path forward is not immediately clear.

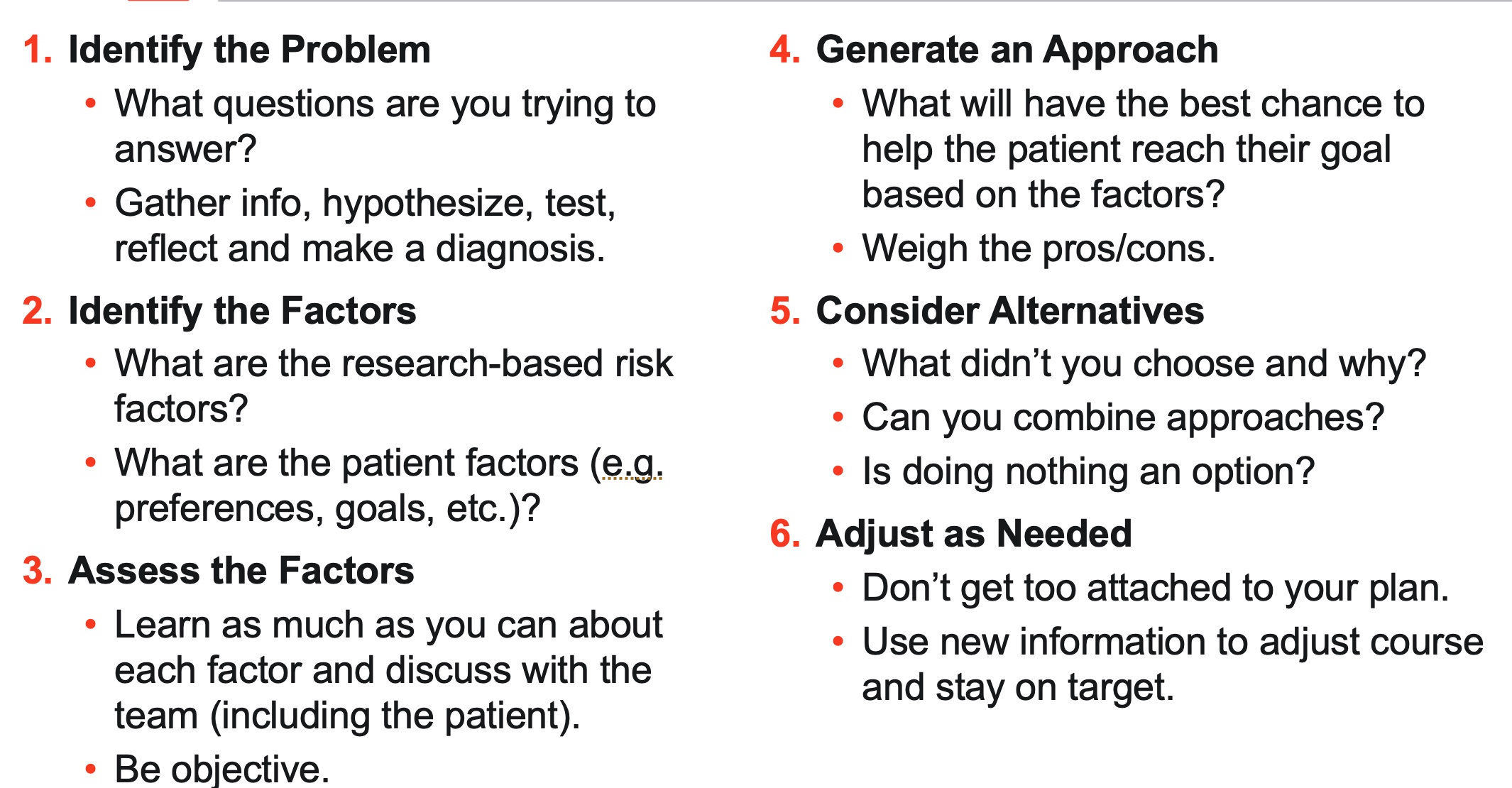

There is nothing particularly unique about this process—it closely resembles the scientific method and draws from various research and literature I have studied. While it is not revolutionary, it has proven effective for me over time. We will go through each step in detail. In summary, here is the framework as identified in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decision Making in 6 Steps.

Begin by gathering as much information as possible through an initial chart review, patient interview, and clinical swallow evaluation. Then, generate a hypothesis: What do you think is happening? What kind of dysphagia or disorder are you observing, and how severe might it be? Test this hypothesis using instrumental studies or standardized measurements, leading to an official diagnosis. This diagnosis should inform not just an accurate decision but a meaningful one. Determine the most critical elements influencing the problem. Assess and learn about the variables that affect the patient’s condition and decision-making process. Ask yourself what intervention has the best chance of helping the patient achieve their goals based on the identified factors. Be sure to consider alternative interventions rather than defaulting to your usual approach. Recognize when an initial approach does not work as expected. Whether it is identifying a mistake or an unforeseen outcome, this step emphasizes adaptability and refining your strategy.

An accurate decision, such as reducing the risk of aspiration, is a crucial part of the process. However, we also aim to make decisions that meaningfully improve the patient’s overall quality of life. Let’s delve into each step in greater detail. A good decision, on the other hand, involves reducing the risk of aspiration pneumonia by thinking beyond just preventing aspiration. This includes strategies such as mobilizing the patient, improving their oral health, and encouraging self-feeding.

Next, let's examine the factors involved. Based on research conducted in long-term acute care settings, I have categorized these factors into two groups:

Risk Factors: These are elements that increase the likelihood of aspiration pneumonia, including:

Medical Stability: The patient's overall health status and ability to withstand interventions.

Risk for Aspiration of Harmful Contents: The potential for inhaling substances that could lead to infection.

Pulmonary Clearance: The efficiency of the respiratory system in clearing aspirated material.

Immune Response: The body's ability to fight infections.

Patient Factors

Preferences, goals, and expectations

Risk tolerance

By assessing these factors, we can develop a comprehensive approach to minimize the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Essentially, any patient at risk for aspiration pneumonia will exhibit variables across each of the identified risk categories. They are likely to be medically fragile to some degree and have a risk of aspirating significant amounts of harmful contents, such as food or liquid, potentially introducing bacteria that can lead to infection—because that is the mechanism through which pneumonia develops. Additionally, such patients often have weak, frail, or compromised lungs that struggle to cough out aspirated contents, combined with an immune system unable to fight off the resulting infection. Together, these factors increase susceptibility to aspiration pneumonia.

On the other hand, we also need to consider patient-specific factors. These include their preferences, goals, expectations, and tolerance for risk. Quantifying these factors can provide valuable insights. While you do not need to follow this exact process, I have found it incredibly helpful in guiding decisions. It essentially answers the question: What direction should we take? Should we prioritize safety and proceed cautiously, or should we lean more toward quality of life, even if it involves taking some risks? This balance is crucial in tailoring care to the patient’s unique situation.

When we weigh patient-specific risks against their preferences, quantifying the information becomes a critical tool to shift us from System 1 (fast, reflexive thinking) toward System 2 (slow, deliberate decision-making). While quantification is often subjective, the very act of assigning values compels us to analyze the information in a structured, thoughtful way. This process helps us think more formally and systematically about both the problem and potential solutions, promoting organized, deliberate decision-making.

By quantifying different variables—risks, benefits, and patient priorities—we can better determine the most relevant factors for each case. This structured approach guides us in selecting an intervention that aligns with the patient's unique goals. Later, in our case study, you will see how this process is applied, making it more tangible.

Step five, considering alternatives, maybe the most critical step, second only to identify the problem. Avoid assuming that the initial course of action is the best one. Follow-up is essential—evaluate how the patient is progressing, assess whether the chosen path is working, and adjust as necessary to provide the best care.

Think of step 6 (adjust as needed), the decision-making process like navigating a sailboat. You do not set the sails in one direction and expect to reach your destination perfectly. Instead, you constantly adjust based on the wind, water, and weather to stay on course. Similarly, generating a list of alternatives in Step Five makes Step Six seamless. If something is not working, you can revisit your list of options and pivot based on new information, ensuring the best possible outcome for the patient.

Bullets Before Cannonballs

We can think about this process through the "bullets before cannonballs" analogy, introduced by Jim Collins in his book Great by Choice. Imagine you are commanding a ship, and an enemy vessel approaches, posing an imminent threat. You have a limited amount of gunpowder—just enough for one cannonball. Instead of immediately using all your resources on a single, uncalibrated cannon shot, you first fire small bullets, observing where they land. The first bullet misses by a significant margin, the second comes closer, and the third hits the target. With this calibrated line of sight, you confidently use your remaining gunpowder to fire a cannonball, striking the enemy ship effectively. In decision-making, this translates to conducting low-risk, low-cost experiments ("bullets") to test and refine your approach before committing substantial resources to a major initiative ("cannonball").

You take all the remaining gunpowder, use the calibrated trajectory, and sink the enemy ship—ensuring survival. This analogy demonstrates the importance of not expending all resources or efforts on an initial, untested decision. Instead, we can proceed cautiously and iteratively, refining our approach as we gather more data.

For example, when working with NPO patients on a feeding tube, if I suspect they might tolerate a regular diet, I adopt a gradual progression. I might begin with ice chips for a day, then move to clear liquids, and eventually introduce a pleasure diet. This step-by-step progression ensures we do not take unnecessary risks or “use all our gunpowder” at once, so to speak, while steadily advancing the patient’s care.

Be Objective

“In God we trust; all others must bring datan (W. Edwards Deming).” Objectivity is essential in clinical decision-making. Dysphagia management often involves assessing probabilities—asking questions like: What are the chances this patient will eat safely? What’s the likelihood of choking, aspirating, or developing aspiration pneumonia?

What Are the Chances?

By treating dysphagia management as a probabilistic challenge, we can rely on data and evidence to guide our decisions, making informed choices that prioritize patient safety and well-being. In managing dysphagia, we often assess the probability of various outcomes, such as safe eating, choking, aspiration, weight changes, or respiratory difficulties. To inform our decisions, we rely on research and literature that provide pertinent statistics. For instance, understanding the base rate of aspiration pneumonia among hospitalized patients is crucial. Research indicates that aspiration pneumonia accounts for approximately 10% of pneumonia cases requiring hospitalization.

This suggests that the majority of hospitalized pneumonia cases are not aspiration-related. Considering such statistics is essential when making clinical decisions, as they help us avoid overestimating the likelihood of aspiration pneumonia and ensure a balanced approach to patient care.

Use Statistics

Unless we have comprehensive information about a patient—especially if it is our first time seeing them and we do not fully understand their condition—we rely on base rates as our starting point. Base rates, informed by literature, provide a foundational understanding of what’s statistically likely for certain conditions. From there, we gather as much additional information as possible to fill in the gaps.

For example, if a patient has Parkinson’s disease, we might research the likelihood of them having dysphagia, aspirating, or developing aspiration pneumonia. These probabilities give us an informed starting point for managing their care.

Of course, we also need to account for the "X factor." The X factor represents the specific information we gather about the patient through direct assessment. For instance, an instrumental swallowing evaluation may confirm aspiration or reveal a history of recurrent aspiration pneumonia. This information identifies the patient as being at high risk for further complications, allowing us to tailor interventions more effectively.

Quantification

Until we have definitive information, we rely on base rates to determine what is most likely to happen. This process revolves around quantification. There are various ways to quantify information, including using scales, measuring tests, or even estimating probabilities based on experience. For example, in the case study, you will see me assess the likelihood of a patient declining after a specific recommendation. I might estimate this at 10% or 15%. While such projections can feel somewhat subjective, they are often informed by prior experience with similar patients, preferably in comparable settings with similar care teams.

To make this process more systematic, I have utilized something called a decision journal. As I mentioned earlier, I have studied the decisions I have made over time. This involves documenting each decision, noting the most critical variables, and revisiting the journal later to evaluate outcomes. For the past few years, I have tracked patients, particularly those transitioning from NPO to PO diets, to determine the percentage who decline after such recommendations. This practice has provided me with a personal base rate to reference, which I can share with patients and care teams during decision-making. It offers a grounded probability to inform and guide recommendations.

Absolutely, while quantification and statistical analysis are valuable tools in clinical decision-making, our greatest asset remains our capacity for compassion and empathy. Understanding and connecting with patients on a human level—acknowledging their feelings, needs, and desires—is fundamental to effective care. Empathy not only enhances patient satisfaction but also leads to better adherence to treatment plans and improved clinical outcomes. By truly listening to our patients and valuing their perspectives, we can provide care that is both scientifically sound and deeply humane.

Confirmatory and Exploratory Thoughts

In clinical practice, our approach to problem-solving can significantly influence patient outcomes. Two distinct cognitive strategies are confirmatory thought and exploratory thought.

- Confirmatory Thought involves forming a hypothesis and seeking evidence to support it. While this approach can streamline decision-making, it may inadvertently lead to confirmation bias, where we focus solely on information that validates our initial beliefs, potentially overlooking alternative explanations.

- Exploratory Thought, on the other hand, entails considering various possibilities and actively seeking information that might challenge our assumptions. This method promotes a more comprehensive understanding of a problem by encouraging open-mindedness and critical evaluation.

Incorporating exploratory thought into our practice can be enhanced through interprofessional collaboration. Engaging with a diverse healthcare team—including nurses, doctors, and fellow speech pathologists—allows us to present our hypotheses and invite colleagues to critically assess them. This collaborative approach leverages the collective expertise of the team, leading to more robust and well-rounded clinical decisions.

Effective interprofessional collaboration has been shown to improve patient outcomes, enhance communication among healthcare providers, and reduce the likelihood of errors. By valuing and integrating diverse perspectives, we can develop more effective and patient-centered care plans.

In summary, balancing confirmatory and exploratory thinking, coupled with active engagement in interdisciplinary collaboration, enriches our clinical reasoning and ultimately benefits patient care.

Case Study

Derek is a 67-year-old male admitted with hypercarbic hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation. His condition progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome, leading to a respiratory-driven cardiac arrest. Complications during his hospital course included a left hemothorax, congestive heart failure, and necrotizing pneumonia. He required intubation for 11 days, followed by the placement of a tracheostomy and the initiation of mechanical ventilation.

His medical history is significant for obstructive sleep apnea (managed with CPAP at night), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), COPD, congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). This complex clinical picture necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, focusing on respiratory support, management of comorbid conditions, and prevention of further complications.

Initial Assessment

On the first day, we conduct our initial assessment. The patient is on the ventilator's assist control (AC) mode, which provides full support and mechanical ventilation. Essentially, the ventilator is doing all the work for him. His Glasgow Coma Scale score is 15, indicating normal cognitive function. Using the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT), he scores a zero, which is excellent—he has no oral health issues.

By day two, there is significant progress. He is transitioned to a trach collar. This shift is rapid, moving from full ventilator support with AC mode and some levels of pressure support to weaning modes and finally to the trach collar. The pace of this transition is remarkable. He is awake, alert, and actively engaging with the process, showing a clear determination to progress. On this day, he also tolerates a speaking valve for an entire hour—a great sign. We’re optimistic, thinking he’s on a smooth path forward.

However, by day three, his progress takes a slight turn. He struggles with the speaking valve, only tolerating it for five minutes before exhibiting increased work of breathing. To evaluate, we perform an arterial blood gas. While the results are within normal limits, the situation feels less stable than the day prior.

Day four brings another positive shift. He now tolerates the speaking valve for three hours, demonstrating noticeable improvement. However, his oxygen saturation (SpO2) fluctuates, ranging from as low as 88% to as high as 95%. While it tends to hover in the low 90s, these levels remain concerning. They prompt us to dig deeper.

First, we focus on establishing a clear baseline. His initial baseline was well within functional limits, but we need more data to fully understand his current state. To do this, we turn to the literature. Our goal is to identify research that closely aligns with our patient population and, more specifically, with his unique case. Finding relevant studies requires a careful approach to ensure the data reflects his circumstances as accurately as possible.

One of the best tools in this process is maintaining a decision journal. This journal allows us to document critical variables as we observe the patient. After the outcomes become clear, we revisit our notes to analyze the full picture. Did we miss anything? Was our perspective complete? Reflecting in this way helps refine our approach, ensuring better decision-making in future cases.

Base Rates

One of the most valuable tools you can use is creating a base rate for your patients. By tracking 50 to 100 patients—a manageable number if you see patients regularly—you can monitor outcomes following your recommendations. This data allows you to identify patterns, anticipate potential risks, and refine your decision-making for future cases.

For instance, let’s consider some statistics from the literature. Dysphagia is reported in 50% of patients after extubation—a substantial number, indicating that half of these patients experience some level of swallowing difficulty. Similarly, having a tracheostomy tube increases the likelihood of silent aspiration to 81%. These figures are striking and highlight the importance of careful consideration when planning interventions.

In this particular case, my concern is the risk of aspiration pneumonia if I proceed with feeding. The patient is medically fragile following a prolonged and challenging hospitalization. To assess this risk, I examine the primary factors contributing to aspiration pneumonia:

- Aspiration Risk: The likelihood of aspirating harmful material.

- Pulmonary Clearance: The patient’s ability to clear aspirated material effectively.

- Immune Response: The capacity to fight off infections resulting from unaddressed aspiration.

By systematically evaluating aspiration, clearance, and immune response factors alongside my own base rate data, I can approach decision-making with both caution and confidence, tailoring care to the patient’s specific needs.

In assessing Derek's risk factors for aspiration pneumonia, we have identified multiple variables across three key categories:

- Aspiration Risk: Factors increasing the likelihood of aspirating harmful material.

- Pulmonary Clearance: The patient's ability to effectively clear aspirated material from the lungs.

- Immune Response: The capacity to combat infections that may result from aspiration.

The presence of multiple risk factors in each category theoretically elevates Derek's overall risk for developing aspiration pneumonia. As we move into the initial phase of our decision-making process, it is crucial to clearly define the problem at hand. A pertinent question to consider is: Is Derek medically stable enough to undergo a swallow evaluation?

Determining medical stability is essential before proceeding with a swallow evaluation. Factors to assess include vital signs, respiratory status, and overall endurance. Ensuring that Derek can tolerate the evaluation will help us obtain accurate results and develop an appropriate management plan. By systematically addressing these considerations, we can make informed decisions aimed at minimizing Derek's risk of aspiration pneumonia while promoting his recovery.

Hypothesis

Next, we consider how to evaluate Derek's swallowing. Should we conduct an instrumental study or a clinical assessment? Additionally, we examine his medical trends: Is his condition improving, worsening, or remaining stable? Can he maintain adequate blood oxygen saturation levels? What are the risks associated with PO intake at this time?

These questions guide a collaborative discussion with the interdisciplinary team. Together, we determine that Derek is stable enough for a swallow evaluation. Given the high risk of silent aspiration associated with a tracheostomy, an instrumental swallowing evaluation is the most appropriate first step.

His medical status currently appears variable—trending up and down—but he has maintained stability and adequate SpO2 levels over the past few days. However, we recognize that the risks remain high and must be factored into our decision-making as we proceed.

At this point, we form a hypothesis: Derek is likely experiencing moderate to severe dysphagia, accompanied by a high risk of dysphagia-related aspiration and subsequent pneumonia.

Hypothesis Testing- Day 4

Given Derek's recent prolonged intubation and current tracheostomy, it is prudent to conduct an instrumental swallowing evaluation to accurately assess his swallowing function. This approach is recommended due to the high incidence of silent aspiration in patients with tracheostomies. While his cranial nerve assessment appears grossly within normal limits, the complexities associated with his medical history necessitate a thorough instrumental assessment to inform an appropriate management plan.

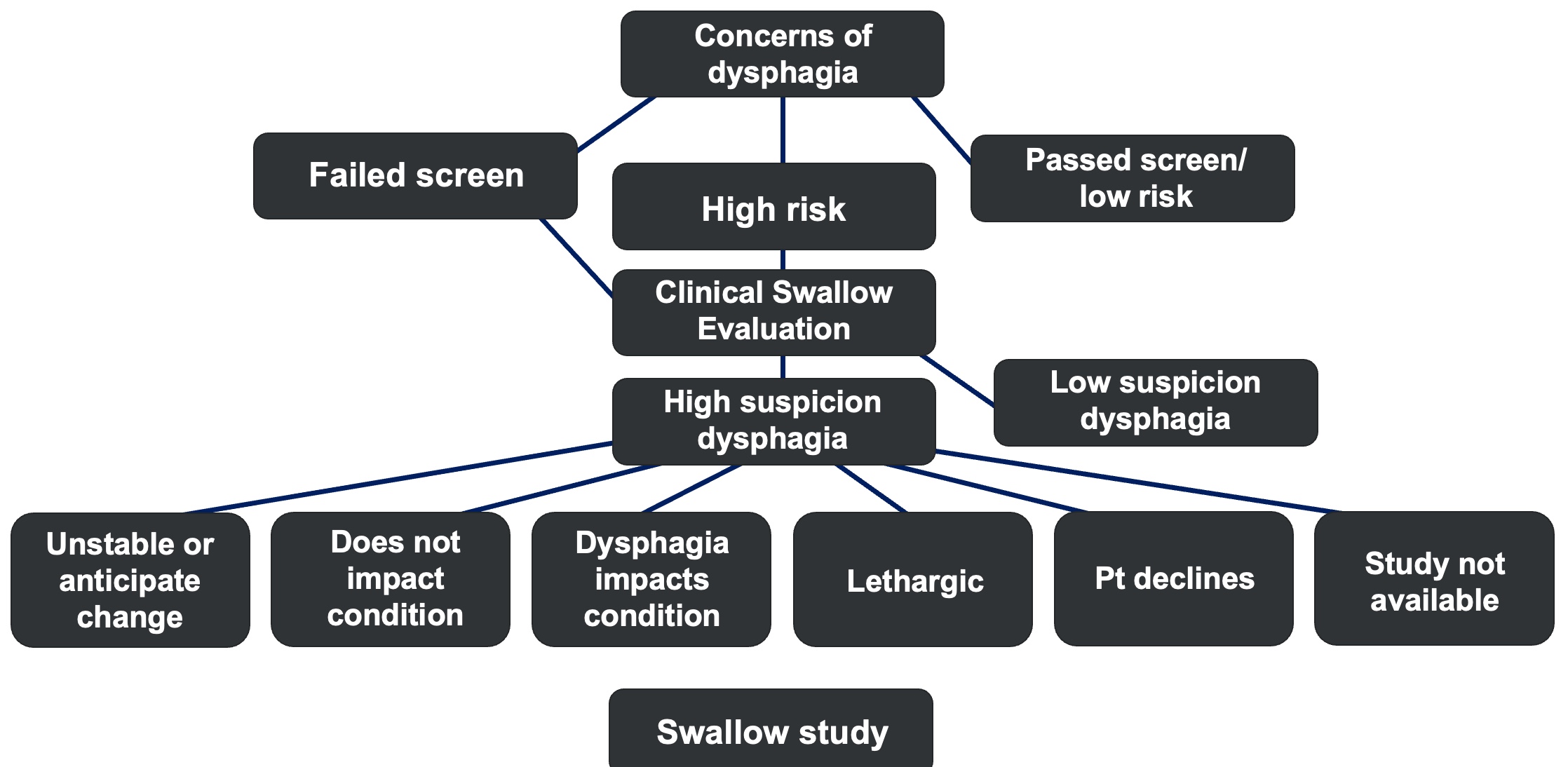

Figure 2. Decision-making algorithm version 1.

Figure 2 provides an algorithm designed to guide your decision-making process. If you find yourself uncertain or on the fence, this chart can help steer you away from "System 1" thinking—those quick, habitual responses like, I will do this because it is what I have always done. Instead, it encourages a "System 2" approach, characterized by deliberate, slower, and more analytical thinking.

Using this algorithm, you can systematically evaluate key questions:

- Are there concerns about dysphagia?

- Is the patient at high risk?

From there, you can incorporate insights from the clinical swallow evaluation. For instance, if the presence of a tracheostomy raises suspicions, alongside other factors, it might suggest the patient is not an ideal candidate for a swallow study. This structured approach ensures that critical considerations are thoughtfully addressed, reducing the chance of oversight in complex cases.

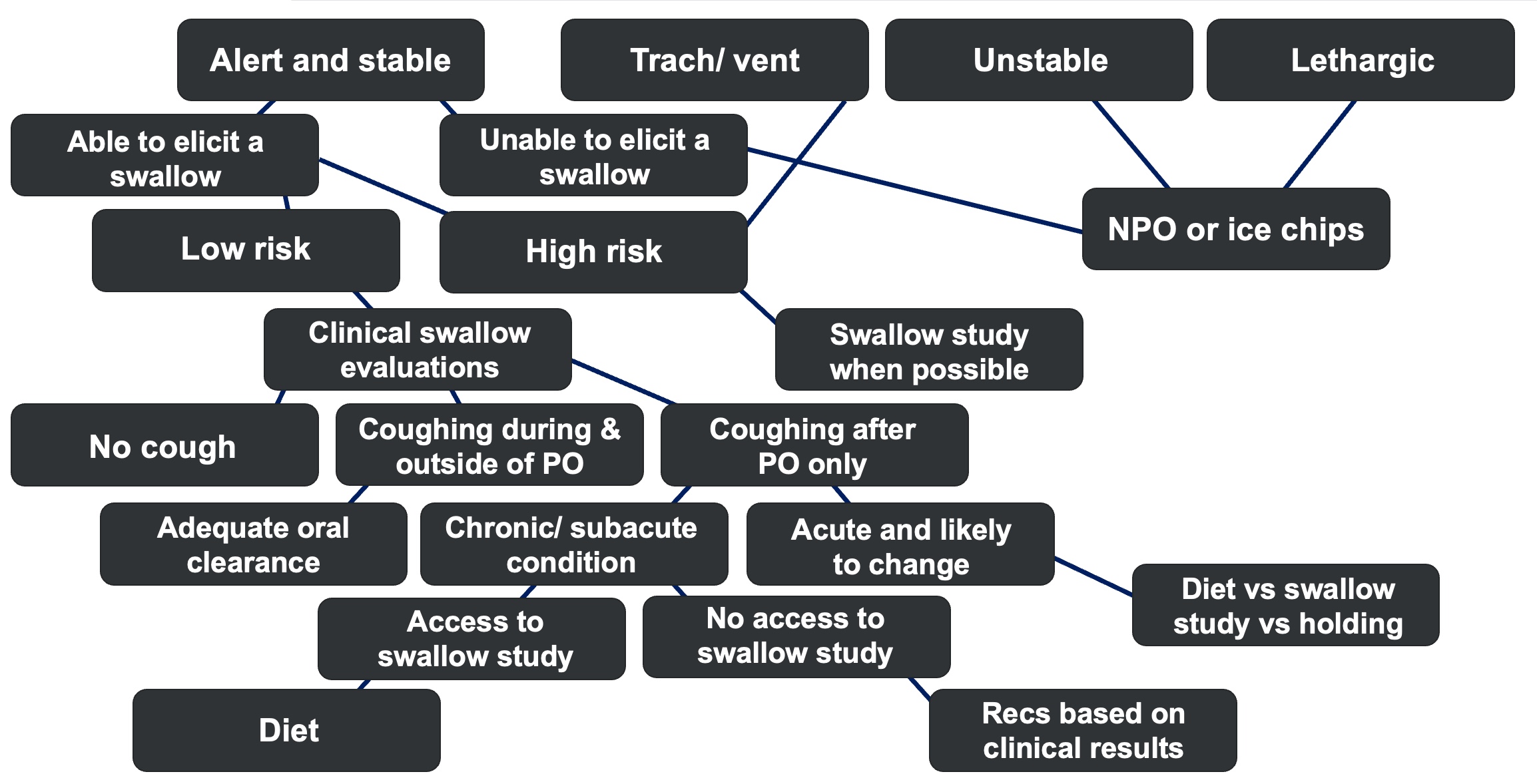

Figure 3. Decision-making algorithm version 2.

Figure 3 presents an alternative approach to assessing swallowing function in patients with tracheostomies and mechanical ventilation, highlighting the complexities involved. An algorithmic framework can be invaluable in guiding clinical decision-making. For example, the Swallow Assessment Algorithm for Mechanically Ventilated Patients with a Tracheostomy, developed at Raigmore Hospital, offers a structured methodology to evaluate and manage these cases effectively.

This algorithm underscores the critical role of interdisciplinary collaboration, comprehensive patient assessments, and the careful use of instrumental evaluations when warranted. By adopting such structured approaches, clinicians can improve both decision-making processes and patient outcomes.

FEES #1 – Day 5

The Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) revealed several notable findings:

Moderate Laryngeal Edema: Swelling in the laryngeal area, which can impede normal swallowing function.

Swallowing Efficiency: Presence of moderate residue in the valleculae and piriform sinuses, indicating reduced efficiency in clearing material during swallowing.

Murray Secretion Scale: A score of 3 was observed, signifying secretions in the airway that are not effectively cleared throughout the study. However, these secretions showed some clearance with the introduction of PO intake.

Penetration-Aspiration Scale: A score of 5 was assigned, indicating deep penetration to the level of the vocal folds without ejection. This suggests timely airway closure that is minimally incomplete, possibly due to incomplete epiglottic retroflexion.

Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale: A score of 3 was noted, corresponding to a moderate to severe level of dysphagia.

These findings collectively point to significant swallowing impairments, underscoring the need for targeted therapeutic interventions to address the identified deficits.

Summary

This is a summary of his exam findings:

Weaknesses:

- Swallowing Impairments: Incomplete airway closure, decreased propulsion, increased secretions, and residue in the valleculae and piriform sinuses.

- Penetration on Large Volumes: Deep penetration occurs only with large volumes of thin liquids.

- Structural and Functional Deficits:

- Decreased base of tongue retraction.

- Reduced posterior pharyngeal wall stripping wave.

- Impaired cricopharyngeal segment opening.

- Incomplete epiglottic retroflexion.

- Possible reduced hyolaryngeal elevation and excursion (not directly observable on FEES).

- Sensory and Protective Issues: Decreased sensation and a weak cough.

Strengths:

- Motivation and Compliance: The patient is highly motivated and able to follow directions effectively.

- Support System: Excellent support from his wife.

- Improved Function with Strategies: Demonstrates better clearance and airway protection when using compensatory strategies, including:

- Small bites and sips.

- Hard, fast swallows.

- Alternating solids and liquids.

- Multiple swallows per bolus.

Recommendations:

- Allow ice chips, limited to no more than three ounces, three times per day.

- Incorporate the compensatory strategies identified as effective during the FEES exam.

- Closely monitor the patient’s progress.

- Emphasize the importance of oral care to reduce aspiration risks.

- Introduce targeted exercises to improve swallowing function.

Decision-Making Process

Let’s go through the steps of our decision-making process for this case.

- Problem:

- What is the problem? The patient has been identified with moderate pharyngeal dysphagia based on the scales reviewed earlier. While initially considered moderate to severe, a further assessment confirmed a moderate classification coupled with an increased risk of decline.

- Identifying the Factors:

- We revisit the four key risk factors: medical complexity, aspiration risk, pulmonary clearance, and immune response. Each factor is subjectively quantified on a scale from 1 to 5.

- For patient factors, such as preferences, goals, and tolerance for risk, we use a scale from 1 to 10 to reflect their higher impact.

- In this case, the patient demonstrates a high level of medical complexity and significant risks in aspiration, poor pulmonary clearance, and weak immune response, all scoring near 5. However, his strong preferences and tolerance for risk score highly as well, reflecting his desire for water and belief in his ability to manage.

- Assess the Factors:

- While patient factors are highly rated, the risk factors slightly outweigh them. This leads us to opt for a cautious intervention.

- After discussing these risks with the patient, he agrees to start with a controlled recommendation: small amounts of ice chips.

- Weighing Costs and Benefits:

- This approach allows us to balance the benefits, such as addressing patient goals and improving quality of life, against the potential costs. Using a quantified, subjective assessment moves us away from reflexive System 1 thinking toward a more deliberate System 2 approach.

- Considering Alternatives:

- By quantifying expectations, we anticipate outcomes. Initially, we estimated a 20% chance of patient decline with this recommendation. With more data gathered from my decision journal, I would now estimate the likelihood closer to 10%, as my records show that fewer than 10% of similar patients experience negative outcomes after starting PO intake.

- Adjusting as Needed:

- Change course as needed

- Use new information to adjust course and stay on target

To minimize risks, we incorporate measures such as strict monitoring, patient education, and adherence to compensatory strategies. These interventions are tailored to address specific risk factors identified during the evaluation. By considering these potential outcomes, we can develop proactive strategies to monitor and address changes in the patient's condition, ensuring timely interventions and optimal care.

FEES #2 – Day 11

Following up with a Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) approximately one week later, we observed significant improvements in the patient's swallowing function:

- Laryngeal Edema:

- Notable reduction, indicating decreased swelling in the laryngeal area.

- Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS):

- Improved from a score of 5 to 2.

- A PAS score of 2 indicates that material enters the airway, remains above the vocal folds, and is ejected from the airway, reflecting transient penetration with effective clearance.

- Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale (DOSS):

- Improved from level 3 to 4.

- Level 4 on the DOSS corresponds to mild-moderate dysphagia, where the patient may require intermittent supervision or cueing and have one or two consistencies restricted.

Summary of Findings:

- Improvements:

- Enhanced airway closure, leading to better protection during swallowing.

- Effective use of compensatory strategies, allowing for safer and more efficient swallowing.

- Persistent Challenges:

- Minimal improvement in sensation and cough reflex, which are crucial for clearing any aspirated material.

Plan:

Given these improvements, we recommend advancing the patient's diet to include pleasure feedings of pureed foods and thin liquids administered with a speaking valve in place. Continuous monitoring will be essential to ensure safety and to make further adjustments as needed.

Decision-Making Steps and Adjustments

In the initial phase, we identified the problem as a mild oropharyngeal swallowing deficit, indicating significant progress. At this stage, patient factors, such as motivation and the ability to tolerate a PO diet, began to outweigh the risk factors. Consequently, the benefits of advancing the diet outweighed the costs, leading us to cautiously progress his intake. We continued to assess alternatives, and as his condition improved, our uncertainty decreased, and confidence grew. However, this led us to Step 6: Adjustment.

On Day 14, the patient's condition changed. He experienced increased CO2 retention and altered mentation, leading to impulsive eating behaviors and coughing on pudding. PO intake was suspected in his tracheal secretions. Revisiting the problem, it shifted back to requiring mechanical ventilation due to CO2 retention. Identifying the factors again, risk factors, including respiratory instability and aspiration concerns, now heavily outweighed patient preferences and goals. The plan involved placing the patient on strict NPO status and conducting ongoing reassessments to monitor improvement.

After a few days, the patient was liberated from the ventilator. Capping trials were initiated, and ABGs remained within acceptable ranges. He continued to use the vent at night due to CO2 retention but tolerated PO intake without significant difficulty during the day. Employing the “bullets before cannonball” approach, we progressed cautiously, starting with pleasure puree feedings, advancing to full trays of puree, and eventually transitioning to a regular diet as tolerance improved. The patient began weaning from the PEG tube while remaining on nocturnal ventilation.

One of the most significant lessons learned was recognizing the potential risks associated with CO2 retention and altered mentation in patients recently liberated from mechanical ventilation. Retained CO2 can lead to confusion and impulsive behaviors, increasing the risk of aspiration. Therefore, it is recommended to always ensure supervision during meals for the first one to two weeks after transitioning to a PO diet post-ventilator liberation. This precaution mitigates risks and promotes safer patient outcomes.

Takeaways

A clinician can only be judged by the quality of the decisions they make. Better decision equals better outcomes. Reflecting on our discussion, several key insights emerge:

Impact of Biases and Heuristics: Cognitive biases and heuristics, while often serving as mental shortcuts, can significantly influence clinical decision-making. These biases may lead to diagnostic errors and affect patient outcomes. Recognizing and addressing these cognitive tendencies is crucial for improving decision quality.

Strategies to Mitigate Cognitive Biases: Implementing structured decision-making processes, such as decision guidelines and quantifiable measurements, can help counteract the limitations imposed by cognitive biases. These tools promote more deliberate and evidence-based decisions, enhancing patient care.

Value of a Team-Based Approach: Engaging in collaborative, interdisciplinary teamwork brings diverse perspectives to the decision-making process. This collective approach enriches problem-solving capabilities and has been associated with improved patient outcomes.

By acknowledging the influence of cognitive biases, employing structured decision-making frameworks, and fostering collaborative teamwork, clinicians can enhance the quality of their decisions, leading to better patient outcomes.

Questions and Answers

Q: Does type 1 and type 2 thinking rely on episodic memory and semantic memory?

A: That could be part of it. I am not as familiar with those terms being explicitly used in the literature I have read, but it sounds like you are likely onto something there. Children with ASD often seem to rely heavily on type 1 thinking, which may be linked to their dependence on episodic memory.

Q: If unable to participate in an instrumental study, how does that affect decision-making? Should we take a chance with changes in PO intake, such as diet, texture, or liquid consistency, with the information we have, or should we be more conservative?

A: This depends on the clinical situation. For instance, if a patient is unable to participate due to a condition like COVID-19, where taking them off the unit risks spreading infection, we must make decisions with the limited information available. This does not mean decisions cannot be made—it means we need to rely heavily on the information we do have. Base rates from research, literature, clinical experience, or documented cases with similar presentations become crucial. Although research can sometimes be limited, it often provides guidance. Speech pathology research is improving daily, offering higher-quality data to help us make decisions when answers are incomplete. However, advocating for an instrumental study and obtaining that data as soon as possible is always ideal.

Q: Do you recommend considering risk factors prior to an instrumental assessment?

A: Definitely. Assessing risk factors early provides a valuable starting point. Reviewing literature, clinical notes, and chart information and collaborating with the interdisciplinary team, patient, and family can help identify risk factors. This initial evaluation sets a baseline, which can be refined with new information obtained from the instrumental swallowing evaluation.

Q: What would be your suggestions to ensure we take the long road if we need to rush?

A: Taking the “long road” involves adopting a System 2 deliberate approach. However, in situations where time is limited, examine why you are in a rush. There could be numerous reasons, such as workload, caseload complexity, or systemic inefficiencies. Addressing these stress points by consulting with your director or administrator can help create manageable workflows, reduce time pressure, and improve decision-making processes even in high-stress environments.

References

Brodsky, M. B., Huang, M., Shanholtz, C., Mendez-Tellez, P. A., Palmer, J. B., Colantuoni, E., & Needham, D. M. (2017). Recovery from dysphagia symptoms after oral endotracheal intubation in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. A 5-year longitudinal study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 14(3), 376-383.

Chalmers, J. M., King, P. L., Spencer, A. J., Wright, F. A. C., & Carter, K. D. (2005). The oral health assessment tool—validity and reliability. Australian dental journal, 50(3), 191-199.

Duke, A. (2019). Thinking in bets: Making smarter decisions when you do not have all the facts. Penguin.

Farnam Street. (2017). Learn faster, think better, and make smart decisions. Available at fs.blog

Featherston, R., Downie, L. E., Vogel, A. P., & Galvin, K. L. (2020). Decision making biases in the allied health professions: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One, 15(10), e0240716.

Feinberg, M. J., Knebl, J., & Tully, J. (1996). Prandial aspiration and pneumonia in an elderly population followed over 3 years. Dysphagia, 11(2), 104-109.

Fukuba, N., Nishida, M., Hayashi, M., Furukawa, N., Ishitobi, H., Nagaoka, M., ... & Shizuku, T. (2020). The relationship between polypharmacy and hospital-stay duration: a retrospective study. Cureus, 12(3).

Groopman, J. E. (2008). How doctors think (1st Mariner books ed.).

Hallett, C. (2005). The attempt to understand puerperal fever in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: the influence of inflammation theory. Medical history, 49(1), 1-28.

Herzig, S. J., Howell, M. D., Ngo, L. H., & Marcantonio, E. R. (2009). Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. Jama, 301(20), 2120-2128.

Jain, S., & Iverson, L. M. (2022). Glasgow Coma Scale. 2022 Jun 21. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow/Farrar. Straus and Giroux.

Sibony, D. K. I. O., & SUNSTEIN, I. C. R. (2022). Noise: A flaw in human judgment.

Kaneoka, A., Pisegna, J. M., Inokuchi, H., Ueha, R., Goto, T., Nito, T., ... & Langmore, S. E. (2018). Relationship between laryngeal sensory deficits, aspiration, and pneumonia in patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia, 33, 192-199.

Kao, A. B., & Couzin, I. D. (2014). Decision accuracy in complex environments is often maximized by small group sizes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1784), 20133305.

Lt, K. (2000). To err is human: building a safer health system. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America.

Kollmeier, B. R. & Keenaghan, M. (2022). Aspiration risk. StatPearls Publishing. NBK470169.

Kuo, C. W., Allen, C. T., Huang, C. C., & Lee, C. J. (2017). Murray secretion scale and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in predicting aspiration in dysphagic patients. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 274, 2513-2519.

Laheij, R. J., Sturkenboom, M. C., Hassing, R. J., Dieleman, J., Stricker, B. H., & Jansen, J. B. (2004). Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid–suppressive drugs. Jama, 292(16), 1955-1960.

Park, P. S., Langmore, S. E., Fries, B. E., & Skarupski, K. A. (2002). Predictors of Aspiration Pneumonia in Nursing Home Residents.

Langmore, S. E. (1998). Laryngeal sensation: a touchy subject. Dysphagia, 13(2), 0093-0094.

Leder, S. B., Suiter, D. M., Murray, J., & Rademaker, A. W. (2013). Can an oral mechanism examination contribute to the assessment of odds of aspiration?. Dysphagia, 28, 370-374.

Manabe, T., Teramoto, S., Tamiya, N., Okochi, J., & Hizawa, N. (2015). Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia in older adults. PloS one, 10(10), e0140060.

Marik, P. E. (2001). Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(9), 665-671. Marvin, S., & Thibeault, S. L. (2021). Predictors of aspiration and silent aspiration in patients with new tracheostomy. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(6), 2554-2560.

Nativ-Zeltzer, N., Nachalon, Y., Kaufman, M. W., Seeni, I. C., Bastea, S., Aulakh, S. S., ... & Belafsky, P. C. (2022). Predictors of aspiration pneumonia and mortality in patients with dysphagia. The Laryngoscope, 132(6), 1172-1176.

Neubauer, P. D., Rademaker, A. W., & Leder, S. B. (2015). The yale pharyngeal residue severity rating scale: an anatomically defined and image-based tool. Dysphagia, 30, 521-528.

Palmer, P. M., & Padilla, A. H. (2022). Risk of an adverse event in individuals who aspirate: a review of current literature on host defenses and individual differences. American journal of speech-language pathology, 31(1), 148-162.

Parrish, S. (2023). Clear thinking: Turning ordinary moments into extraordinary results. Penguin.

Pinker, S. (2022). Rationality: What it is, why it seems scarce, why it matters. Penguin.

O'Neil, K. H., Purdy, M., Falk, J., & Gallo, L. (1999). The dysphagia outcome and severity scale. Dysphagia, 14, 139-145.

Rosenbek, J. C., Robbins, J. A., Roecker, E. B., Coyle, J. L., & Wood, J. L. (1996). A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia, 11, 93-98.

Saposnik, G., Redelmeier, D., Ruff, C. C., & Tobler, P. N. (2016). Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 16, 1-14.

Sibony, O. (2020). you are about to make a terrible mistake!: How biases distort decision-making and what you can do to fight them. Swift Press.

Taylor, J. K., Fleming, G. B., Singanayagam, A., Hill, A. T., & Chalmers, J. D. (2013). Risk factors for aspiration in community-acquired pneumonia: analysis of a hospitalized UK cohort. The American journal of medicine, 126(11), 995-1001.

Tetlock, P. E., & Gardner, D. (2016). Superforecasting: The art and science of prediction. Random House.

Citation

Barnes, G. (2024). Medically complex decision-making for the SLP. Continued.com - Speech Pathology, Article 20711. Available at www.speechpathology.com.