Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, Decision-Making for Alternate Nutrition and Hydration - Part 2.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List at least three criteria utilized by medical professionals in making recommendations for ANH.

- Identify benefits and burdens of artificial nutrition and hydration versus oral intake in two disease processes.

- List at least three poor prognostic indicators for placement of artificial nutrition and hydration.

Introduction

In this course, we'll be touching on the benefits and burdens of ANH versus oral intake. We'll be looking at various disease processes, including COVID. We will talk about patient-centered care and educating the patient and family using the teach-back method. We want to make sure that education about the benefits and burdens is at a comprehension level that the patient and family can understand so that they can make an informed decision. We want them to be able to understand their options and pick the one that's most appropriate for them whether we agree with their choice or not.

Course Agenda

Our course agenda includes looking at the criteria used to make recommendations, reviewing current literature, benefits and burdens of PEG versus oral feeding, comfort feeding, and careful attentive hand feeding in various disorders and disease processes.

We'll also cover some decision-making tools, algorithms, and poor prognostic indicators. We'll touch on waivers and why they are not recommended. I think there are some facilities that are still using them. However, what is better to use is a process for patient-centered choice or to at least have very detailed documentation from a patient care meeting or a very detailed note.

Frequently Asked Questions About

Alternative Nutrition and Hydration (ANH) in Dysphagia Care

When considering Alternative Nutrition and Hydration (ANH) as an option for a patient, there are several things that we need to keep in mind. The patient may have advanced directives. We don't really need to look at those unless the patient is not decisional; they've put a plan in place but can't communicate that to us. If the patient is cognitively intact and has decision-making capacity, we're going to have that discussion with them.

We're also looking at the patient’s nutrition status. Most of the time, a dietician is involved in that. He or she may have looked at appetite stimulants. She may have done a three-day calorie count where we can actually see exactly how much the patient is taking in. If this isn’t working for the patient, then we need to figure out another option.

We want to know what the patient’s medical status is and what is in their medical history. I'm sure you've seen patients who have multiple pages of disorders and the more they have going on, the more likely it is that there is a domino effect.

As far as healthcare, we need to consider behavioral and cognitive status. In certain disorders, where there is a dementia component, that is going to be a patient that's a little bit more difficult. For example, patients with dementia who have had an NG or PEG placed, tend to self-extubate. So, it’s very important to keep that in mind when thinking about ANH.

ANH Options

There are numerous ANH options we can consider for our patients. It is not my determination alone, the entire team comes together to understand the various options. The dietician, the doctor, the SLP, etc. are all discussing what the best option is for the individual.

One long-term option is the PEG. However, if the gut isn’t functioning then we need to do TPN. A short-term option is the NG tube. If we have a patient that has mild to moderate dehydration, then hypodermoclysis might be an option and is cheaper than IVs. We may want to move into the careful attentive hand feeding, where we're assisting. We offer food and liquid to the patient and do not pressure them. We're providing oral intake when they are showing an interest. Finally, we can provide comfort care.

TPN (Total Parenteral Nutrition) or IVH (Intravenous Hyperalimentation)

Looking specifically at TPN, this is an option when the gut is not functioning. The patient can't ingest the calories that they need to stay hydrated and nourished.

If the GI tract is functional then TPN is not an option or if a patient needs supplemental nutrition for less than five days, this is not an option. Again, TPN is more of a doctor's recommendation than ours. If a patient has a terminal illness this is not going to be effective for the anorexia that is associated with the disease processes. Additionally, there is no significant benefit of TPN for cancer patients going through chemo and radiation. In fact, it can create complications that would decrease survival. The literature also suggests that TPN is not efficacious for patients who have a terminal illness.

Albumin

One factor that physicians will look at when making a decision is the patient’s albumin level, which measures the protein in the blood. Obviously, there is an acceptable range. Low levels of albumin indicate that there's an issue with either the liver or the kidneys, which in turn, affects the patient’s survival. A normal level would be 3.4-5.4g/dl or 35-50 g/l. The research suggests that there is a link between a patient’s albumin level pre-PEG placement and mortality rate after the PEG has been placed. If a patient’s albumin level is low, there is a higher mortality rate post-PEG placement.

Factors to Consider in Assessment

There are other factors to consider as well. Poor outcomes and increased mortality have been found to occur in individuals older than 60. In fact, that age group tends to have the highest 30-day mortality rate. Clearly, age has an impact.

Decreased body mass index (BMI) is indicative of malnutrition. What I've seen in some charts over the last couple of years is they're not just talking about calorie malnutrition. They're talking about protein malnutrition. The person is not taking in enough protein to actually do any kind of healing.

Another factor to consider is the more comorbidities the person has, the worse it is for them, as far as PEG placement. This is particularly true with diabetes and cardiac issues. Those pose a significant risk factor. If we are to consider PEG placement for patients with those comorbidities, there tends to be a higher mortality rate. If we add diminished mental capacity to the age factor, then the mortality rate triples.

Medical Ethics

With medical ethics, we want to consider benefits versus burdens. Not everything we can do will always be beneficial to the patient. They can actually be detrimental to our patients. Just because we have the technology to provide ANH, doesn’t necessarily mean that we should do with everyone.

As with everything, it’s on a case-by-case basis. We need to look at the pros and the cons, and then educate patients and families based on that. We must consider the harm to the patient. What is the pain going to be with this particular option? What are the psychological consequences going to be with placement of a PEG? There are social consequences, economic consequences. We need to share with patients that even if they agree to a certain option or procedure, they need to be prepared for some of the issues that they might run into. For example, a particular option could pose a problem with intimacy. A PEG placement can cause negative reactions from friends and family. So, patients need to be prepared.

There is an organization called ASPEN for nutritional support. They state that it is perfectly ethical to withdraw alternate forms of nutrition and hydration if a patient has advanced dementia and they need to be restrained so that they don’t self-extubate. What happens when they self-extubate is we put it back in and they pull it out again, which can create a lot of issues. ASPEN states that with that type of individual, if you're constantly needing to restrain them, then this really is doing more harm than good.

Decision Making and Evidence-Based Practice: What does the literature say?

Currently, we are dealing with COVID and it has been found that if a person is in ICU and has been intubated, chances are they’re going to have a prolonged stay. Chances are they’re going to have inadequate oral intake. So, there will be calorie malnutrition, protein malnutrition, and GI issues occurring.

This situation has been looked at and it is thought that enteral nutrition (EN) is appropriate because it stimulates the gut. Even if there are GI issues such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain, stimulating the gut and providing nutrition is still thought to be beneficial.

There are nutritional guidelines for a patient who has COVID. We need to maintain gut function and immune function with EN. Optimally, if the patient can eat by mouth, that is the preferred method because when they are chewing and swallowing, they are making those muscles work. If they have a feeding tube, whether it's an NG or a PEG, they're not swallowing as often because they're not taking anything in orally. If there is no saliva, then they are not even swallowing that. As a result, muscle disuse atrophy kicks in fairly quickly.

If a patient’s nutritional needs can’t be met orally, the NG tube is recommended. That is the preferred option compared to a central or peripheral vein to provide nutrition because that comes with its own set of complications. If nutritional needs cannot be met with the NG tube, and you've gone through all the strategies you can think of to maximize nutrition, then you have to consider using the PN (central or the peripheral vein) to maintain nutrition at that point. It's really important.

Placement of enteral access such as an NG is an aerosol-generating procedure that will cause the patient to cough. Therefore, anyone in the room at that time is going to be exposed to the aerosols and droplets. It is critical to have your PPE and to limit the number of individuals in the room.

It is suggested to use a large bore NG tube because it has a reduced risk of occlusion during feeding compared to the small ones. Additionally, it won't require the frequent changes that a small-bore would.

Stroke

The literature has documented that stroke patients have an increased risk of death or poor neurological outcomes with PEG versus NG. There's a high 30-day mortality rate and a lot of complications with PEGs. Unfortunately, many individuals are not kept in hospitals as long as they used to be and other facilities won’t take a patient if they have an NG tube in place. Oftentimes, even though the literature is showing that placing a PEG early on in a stroke patient is not a good idea, it’s happening anyway.

ALS/Neurodegenerative Diseases

With ALS or neurodegenerative diseases, PEG placement does improve quality of life scores and can help with weight gain, but it's not going to change mortality. There is still going to be a death.

Dementia

In dementia patients, feeding tubes are ineffective as far as prolonging life, reversing the disease process, or preventing aspiration with advanced dementia. Therefore, it is not a good idea to place a tube in a patient who has advanced dementia but we know it happens.

CVA and PEG

Many individuals who have had a stroke, regain a swallow within two weeks following their infarct. If we're placing a PEG too quickly it does have a high mortality rate because of the stroke. Based on a number of studies, it is suggested that PEG should only be considered if the swallow hasn't come back within four weeks. And yet, we know people are getting PEGs within a matter of days. It is recommended that an NG tube is placed during the acute stages of stroke. But, again, if you need to discharge this patient to a facility, finding one that will take them with an NG tube is difficult. So, the PEG placement seems to be driven by the inability to discharge a patient with an NG tube to a facility.

Advanced Dementia (AD)

We discuss the advanced dementia patient in Part 1. To review, they lose interest in food, they’re too confused to focus, and they don’t know what they’re supposed to do anymore so they going to turn their head away from food or clamp their mouth shut. They are not accepting the food when we approach them or they refuse or can't self-feed.

The Cochrane review has found that there is no evidence that enteral tube feeding provides any benefit for survival time, quality of life, or reduces incidents of pressure ulcers. There is no real benefit to placing a tube in a patient with advanced dementia. However, we know that it happens.

What is suggested, instead, in the literature for patients with advanced dementia, is careful, attentive hand-feeding. We talked about several different types of hand-feeding we can do with our patients in Part 1. But the tube feeding is not going to reverse anything that's going on with this individual. Sometimes families will hear somebody talk about a feeding tube and they are going to jump on the idea that this is going to make their family member better. But, it won't. It is only going to add to the problems.

Dementia

If an individual is cognitively impaired and there is a dementia component, we can do oral nutrition supplements to help improve nutrition. Sometimes an appetite stimulant works. It has also been found that there are situations where placing ANH in a patient with mild to moderate dementia may be appropriate. What the literature states is that it would be ethical if the reason behind the poor nutritional intake is not related to the dementia, rather it's related to another potentially reversible condition. So, it can get the patient over the hump from whatever that new medical concern is, and then we can stop it. So, there is no reason to continue with a feeding tube in a person who has dementia. But if there is an issue that can be reversed, then the feeding tube may be appropriate temporarily.

Cancer Patients & Eating Related Distress (ERD)

If a patient is suffering from cancer, they may have eating-related distress. Cancer patients tend to vacillate between fighting hard to beat the cancer and letting nature take its course. They tend to go back and forth between these two approaches and we see that with the family as well.

If patients are having eating-related distress, these individuals tend to self-isolate. They don't want to be with family because of the pressure that's put on them to eat. So, they may lie they already ate when the family says, “Hey, how about if we go out to eat?” They don't want to go out and eat and be pressured by their family to take another bite or to keep going. You will start to see changes in their food preferences and their eating habits.

The family doesn’t see this weight loss as part of the disease process. They don’t recognize that the patient isn't dying because they're not eating. They're not eating because they're dying. Once the family understands that, it can make the biggest difference in decreasing the conflict with eating. The family will put pressure on the individual and then they feel guilty because they were pushing them to eat. It becomes a really difficult situation with families and patients. Again, patients will self-isolate so they don't have to deal with that.

ESPN – European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism

The European Society for Nutrition states that there is no benefit to using ANH with a patient who has cancer in the advanced disease stages. They also are recognizing that we need to look at a lot of different factors such as culture, religion, spiritual, ethnic backgrounds, etc. All of those factors need to be brought into the picture. The decision for or against ANH is not simply based on what happened on the MBS or during the bedside evaluation.

It has been found that doing careful, attentive hand-feeding of small amounts of food when the patient is willing to accept it has a significant benefit. It's something that the family can do, once they remove that pressure component. It can be a nice way for families to reconnect with their loved ones. The patient is still autonomous and they have their dignity intact, but the conflict has decreased.

SLP Recommendations for ANH with Head/Neck Cancer

For a patient who has had head/neck cancer, we definitely want to make sure that our recommendation is going to be the best approach for them at this particular time. For example, are we going to use compensatory strategies? Are we going to do any type of therapy to try to recover the swallow? If they can safely eat orally then there's no need to have an ANH discussion. We're always going to need to review and assess what the risk factors are before we go into that ANH discussion. When we do have that discussion, are we looking at short-term or are we looking at long-term?

This is where the multidisciplinary team meeting is very critical. We can meet with the patient and the caregivers and have a good discussion so that whatever they decide we want it to be informed and educated. They've received all the information and they've made their choice.

PEG vs. NG with Cancer Patients

There are varying opinions about what is best for the cancer patient, as far as ANH. Should we go the PEG route or the NG? There are so many different opinions. A 2011 study suggested that PEG was superior to the NG because there was better weight gain and lower mortality. Other studies say the NG is better because the complication risk is lower and they have a better chance of recovering and going back to oral intake after about six months. The individual who has an NG tube tends to be more interested in and getting rid of that tube, perhaps more so than the patient with the PEG. Therefore, it is thought that partial oral intake will decrease the muscle tissue atrophy that kicks in because the patient is not eating and drinking normally. As a result of that partial oral intake, the patient will have a quicker return.

There is a study listed in the references that looked at a different kind of tube feeding called intermittent tube feed (ITF). With ITF, the NG tube is not in place 24 hours a day. It's only inserted when it's time to eat, drink or take medication and then it is removed. This is beneficial because there is no tube for most of their days and is not as distressing. Additionally, with the process of inserting that NG, it creates a swallow. The patient starts to get that reflex back and it actually increases epiglottic inversion. It also helps with the residue that you'll see after the swallow.

Research shows that the NG tube actually impairs a normal swallow. But it's suggested that the intermittent is better than having the NG tube in place 24 hours a day.

Nutritional Support at End-of-Life

The goal of nutritional support at the end of life is to optimize quality of life and comfort. We're going to provide patients food and drink when they're interested but we don't pressure them to do so. We need to talk to the family if they are wanting to tube feed that patient. We need to look at the benefits and burdens. It’s suggested that we specifically consider how long the patient would survive if they were starving versus how long would they survive the spread of the tumor, for example? Which one is longer?

Factors Determining Return to Oral Intake Post ANH

When looking at factors for returning to oral intake, it does help if the patient has had some therapy beforehand. In fact, they're talking about interventions to regain swallow before the PEG is even placed. We, as SLPs, can get things going. We can train patients on non-swallowing exercises that they can do to keep things moving. Additionally, we need to consider how severe the dysphagia is. Age is a factor as is what created the need for the PEG tube. All of those factors should be considered for our patients.

Risk Factors

Just because there are risk factors, doesn't mean a patient won't get a PEG. We know that there's a high mortality rate but we see patients going for a PEG tube placement regardless of all the literature that we've been talking about.

I find the following numbers to be very interesting. There is a significant increase in PEG placement in patients older than 65. In 1989, there were 15,000 PEGs inserted. In 1992, that number jumped to 75,000 and increase again in 1995 to 123,000. The latest study in 2016 is still showing 123,000 PEG tube placements per year. That's a lot, and maybe they shouldn't be placing PEGs in some of those people.

Tube Feeding in Palliative Care?

Should tube feeding be done in palliative care? In my experience, once a patient is in hospice, we are not considering a tube. That is the case sometimes with palliative care as well. But we need to take a look at what our goal is. If the goal is to prolong life in acute situations, the data is the strongest for supporting that in patients who have a reversible illness. If our goal is to prolong life and the patient has a chronic disease, we don't have very strong data showing that tube feeding is a good idea.

We know that with anorexia/dysphagia, those are markers for severe multi-system disease and that has a high mortality rate, even if we did do the tube feed. Additionally, if our goal is to prevent aspiration, there is no data to support the idea that tube feeding will actually reduce the aspiration. In fact, we see a higher incidence of aspiration pneumonia in patients who have the feeding tube. This is true for improving comfort. There are no studies that show there's improved quality of life with tube feeding.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: General Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Non-Cancer Diseases

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization has guidelines for specific disease processes and prognosis. Their guidelines suggest that the following diseases have a probable death within six months:

- Heart disease

- Pulmonary disease

- Dementia

- Human immunodeficiency virus disease

- Liver disease, advanced cirrhosis

- Renal disease

- Acute stroke and coma

- Chronic after stroke

The patient needs to meet certain criteria: the condition is life-limiting and the patient has elected to relieve the symptoms rather than treat the underlying disease. The patient either has a documented progression of a disease, or they have impaired nutritional status. Recent impaired nutritional status is related to the terminal process.

Palliative Care and Advanced Dementia

In advanced dementia, palliative care does provide some benefits. A study found that families and caregivers who saw a video of a patient with advanced dementia were more likely to opt for comfort as the goal rather than a feeding tube versus the individuals who were just told about a feeding tube. It's one thing to see a patient with advanced dementia versus just being given verbal information. So, those guides and aids that we give to our patients’ families are really important if they are the decision-makers. They need to know how dementia works, how is it going to progress, what do they need to be prepared for. What are the risks if they choose to have ANH or if they choose to do assisted oral feeding? By giving patients and families this information, it can really help cut down on the conflicts for that decision.

Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Gastrostomy Tube Placement After Intracerebral Hemorrhage in US

There are disparities in the placement of PEG tubes. In a particular study, researchers were looking at patients who had an intracerebral hemorrhage. They looked at almost 50,000 individuals who were admitted with that diagnosis and found that there was a higher PEG placement in minorities, especially those patients who were in a small or medium-sized hospital versus a larger hospital. A patient also had higher PEG placement if they were on Medicaid and had a low household income.

Another study looked at two separate years, 2000 and 2010. They found greater PEG placement in the very young and the very old, non-white males and those who live more frequently on the East coast. I haven't seen an explanation for why the East coast versus anywhere else.

This next statement is really interesting and tells us a bit about experience. The study also found that the longer you were out of med school, the less likely you were to refer a patient for a PEG.

Mortality Trend & Predictors of Mortality in Dysphagic Stroke Patients Post-PEG

Here is another study that looked at a patient who had a stroke dysphagia. Three factors - age of the individual, ASA score, and albumin level - were the criteria used to select patients who were likely to survive three or more months, post-PEG placement. The ASA score (American Society of Anesthesia) is the patient’s physical state or how ill the person is. This score really determines everything. An ASA score of 1 indicates the person is healthy while a score of 6 indicates a person is experiencing brain death, and we’re considering surgical procedures to remove organs for transplant. So, the higher the ASA score the worse it is. Again, age, ASA score and albumin were used to help predict who will survive that PEG placement.

Poor Prognostic Indicators

Below is a list of poor prognostic indicators and the more of these a person has, the worse it is for them.

- Over age 75

- Male

- DM

- COPD

- Advanced cancer

- Previous aspiration

- NPO x 7 days

- Cardiac Disease Confusion

- Pressure sores

- Bedridden

- Hospitalized

- Albumin <3g/dL

- Low BMI

- Charlson score >3 (comorbidity score)

- UTI(5)

If a patient has just one poor prognostic indicator for PEG that is not so bad, but if a person has several, then there is a domino effect. Researchers looked at over 7,000 individuals who came in for PEG tube placement. Twenty-three percent died during the hospital admission for placement with a median survival of about 7.5 months. Usually, the patients that they were placing PEGs had a terminal phase of an illness. Therefore, we must ask why these individuals were even considered for a PEG?

Options for Patients

So, what do we do with these individuals? Rehabilitation might be an option if we think we can get them back to a baseline of safe, self-feeding. NPO status and tube feeding (TF) could actually improve the patient's status.

Are we just going to provide maintenance and maintain the person’s nutrition and hydration? This might be the person that we're looking at that PEG tube. And when they become more alert, we could begin to offer them oral intake and pleasure feeds.

Should we consider palliative care? We can look at long-term and short-term tube feeding, but there are questionable outcomes for many of our patients who are in palliative care.

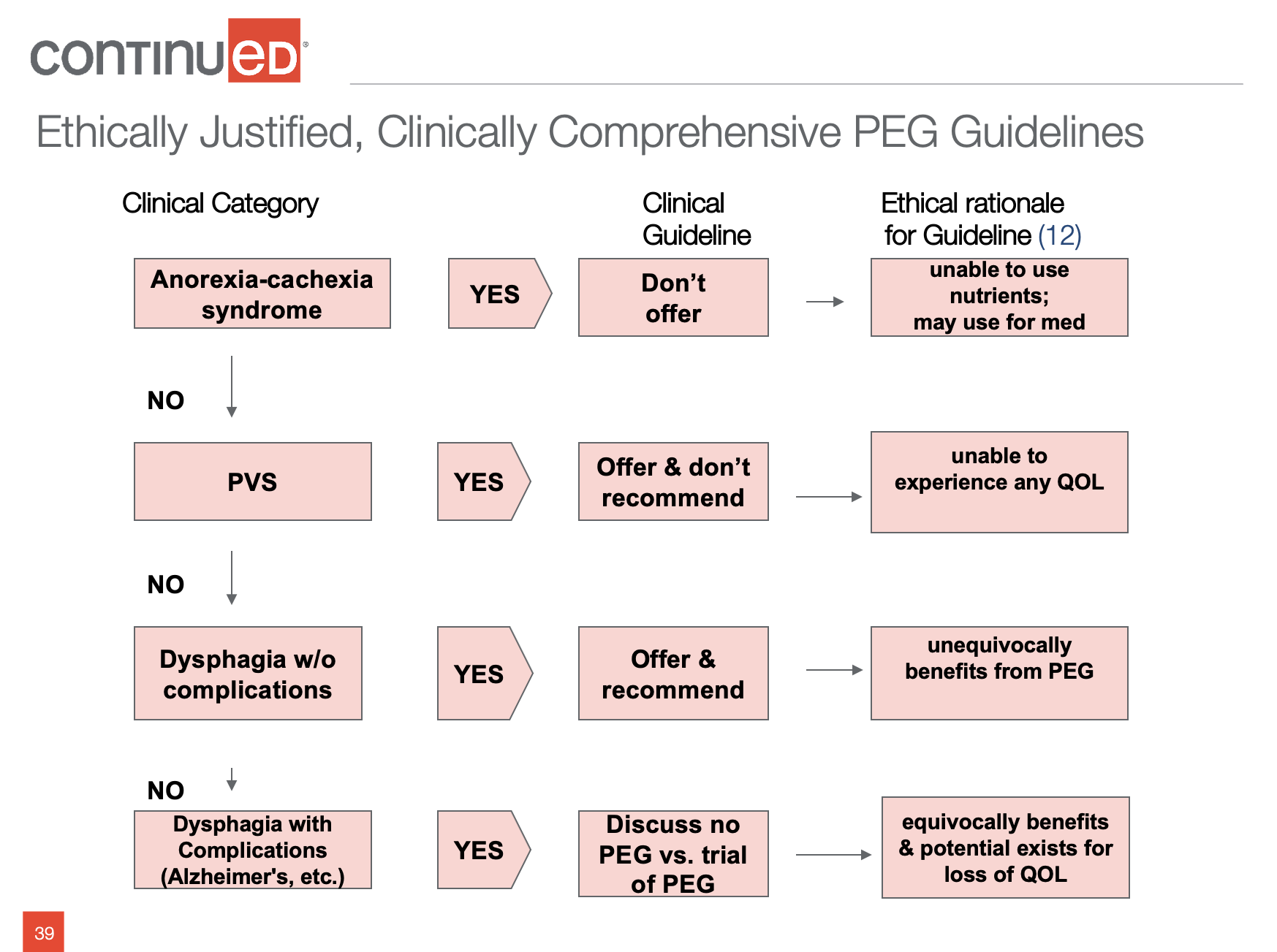

Ethically Justified, Clinically Comprehensive PEG Guidelines

When looking at different guidelines to determine who should be offered and who should not be offered PEG, there are many different options, algorithms and decision-making trees to consider. The one below is called the ethically justified clinically comprehensive PEG guidelines.

Figure 1. PEG placement guidelines.

The table lists the clinical category, the clinical guidelines (i.e., Should we offer, should we not offer), and the ethical rationale for the decision. For example, the clinical guideline for anorexia cachexia syndrome is to not offer a feeding tube because the patient is unable to absorb the nutrients. However, it is also suggesting that the tube could be placed to administer medication.

For persistent vegetative state (PVS), the tube can be placed, but it is not recommended because the patient won’t be able to experience any quality of life. It can take anywhere from 3-12 months for a true diagnosis of persistent vegetative state. So, what do we do in the meantime? Most of what I read in the end-of-life literature is once there is an affirmative diagnosis of PVS, should the tube be removed? That's a really tough call for families to make. They're always hoping for that “miracle” that you read about where somebody woke up after years and they're talking, etc. Unfortunately, that doesn't happen very often. Usually, with PVS we're having the discussion of withdrawing the tube and that's very hard for families.

The last clinical category listed is dysphagia with complications and the guideline suggests discussing no PEG versus trial PEG. Again, this is one chart that you can refer to for PEG placement guidelines.

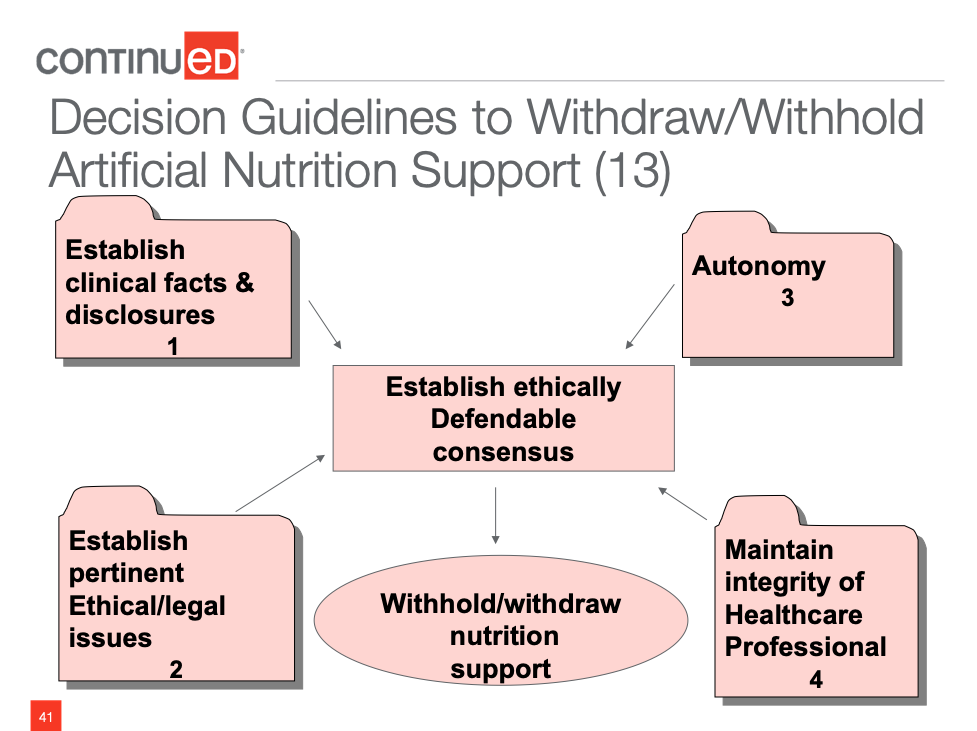

Another option is the decision guidelines to withdraw or withhold ANH (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Decision Guidelines to Withdraw or Withhold ANH.

We're looking at the clinical facts (i.e., What's going on with this individual?). We are considering ethical and legal issues. Does this patient have autonomy (i.e., Can they make their choices?)? We're looking at the healthcare profession and what our spin is on things. When you put all of that together, you're coming up with an ethically defendable consensus about withholding/withdrawing nutrition support. Again, removal is really hard on the family so we want to have a good discussion on each one of those categories.

With persistent vegetative state, we can offer but advise against. As I said, most likely, the patient already has a tube when that diagnosis is made.

If a patient has uncomplicated dysphagia with no other quality of life issues, we can offer and recommend tube placement. Offering and advising against tube feeding would be for end-stage dementia or PVS. We can offer and recommend tube feeding for:

- Bowel obstruction with prognosis, unable to place stent

- Cancer treatment with mod/severe malnutrition & intact GI

- Dysphagia with obtundation;

- Brain stem CVA, bilateral stroke

- Gross aspiration

PEG versus no PEG

To my knowledge, I've never had a COPD patient who had a PEG or an NG tube. But we can have that discussion with them. How severe is this dysphagia? Do you think this is going to be short-term? Can we do an NG and improve that swallow? If it doesn't work, then we can go to the PEG. Too many times we go to the PEG first and ask questions later.

Most Evidence-Based Decision-Making Tool

Dr. Planck is a physician who wrote an article on whether to PEG or not to PEG. He suggests the following.

Do not offer it for:

- Aspiration

- Cancer with short life expectancy

- Dementia

- PVS

- Anorexic-cachexia syndrome

Offer and Recommend:

- Head & neck cancer

- Acute CVA with persistent dysphagia 30 days post discharge (30 day wait decreases fatalities)

- Neuromuscular dystrophy syndromes

- Gastric decompressions

Current Literature

We should only consider placing ANH in a patient where we have evidence-based indications that there is benefit to the patient. It’s important that the doctor doesn't use the PEG placement to avoid difficult discussions about goals of care or prognosis. There are many times when the patient’s family hardly even has a conversation with the doctor.

We want to reduce the overuse of PEG. We need to refer to the literature to determine what it says about a PEG placement in an individual who has a particular situation. Everything is patient-specific.

Clinical Ethical Decision-Making Chart

This chart looks at what's going on with the individual. What's their prognosis? Are we prolonging life or prolonging death? There is a big difference between the two. What are the patient preferences? This is where we need to consider the patient’s culture and/or quality of life. Can they make their own decisions? Who should decide? What is the standard of care, family preferences, et cetera?

ANH Withdrawing or Withholding

Remember that if we are considering withdrawing ANH, the patient already has the tube in place. Again, taking it out can be a tough call for the family. It is suggested that we withdraw if the patient is in a persistent vegetative state, or they're in a state of severe and permanent paralysis. This is the individual who is very aware of their suffering and has decided that they don’t want it anymore. So, the person is decisional.

The other option is to withhold or forego ANH which would apply to a dementia patient, for example. It’s important to note that doctors may not legally end life BUT they are not ethically or legally required to prolong the process of dying.

There really isn’t any ethical difference between withholding and withdrawing ANH. Withdrawing is more psychologically damaging to the family. There are a lot of emotions behind that decision and who is the surrogate decision-maker? We must be sure to look at the patient's plan and honor it.

When to Withdraw/Withhold Artificial Fluids and Nutrition

There are times when it would be ethically appropriate to either withdraw or withhold ANH. According to a 2010 Aspen position paper, there are two categories when this is ethical. One of the situations is a patient who is terminally ill, imminently dying, or dying. Aspen defines that individual as having a six-month life expectancy.

They found that if a patient is terminal but we continue to hydrate them, that increases GI fluids and causes a lot of nausea and vomiting. It increases respiratory secretions which require more suctioning. The patient will also have swelling that causes a lot of pain and discomfort. When a person is at the end of life, there is little interest or desire to eat and drink. So, limiting would be beneficial to that individual.

The other condition the position paper discusses is when a patient has an illness or a disabling condition that is severe and can't be reversed. Aspen defines this as the individual is kept alive but they are not mentally competent or functional without life-sustaining support. However, the patient must meet some requirements before it is appropriate to limit artificial nutrition/hydration:

- They've lost the ability to eat and drink normally and, therefore, need ANH to survive.

- They have a basic medical or neurological condition that creates a substantial and irreversible disabling condition.

When there's no benefit to ANH, we need to talk about withdrawing it. If a competent individual wants it withdrawn, they have every right to say that. If the surrogate is following the advanced directives, they can also have it withdrawn. But, again, we need that team approach to talk about it so that we are making an educated, informed decision that it’s not in the patient's best interest to continue down this road.

Implications of Withdrawing Artificial Nutrition and Hydration from Adults in Critical Care

What happens when we withdraw ANH? A lot happens 24 hours after ANH has been removed. The body is breaking down glycogen into glucose, and that is sustaining. For about eight days or so, that protein catabolism is going to ensure survival. The patient is going to burn fat and that provides nutrition to tissues and the CNS.

Then there is a gradual onset of death. It is thought that happens when a person has no passage of urine. The systems shut down.

ANH & IV in Dying Patients

ANH or IV in individuals who are dying creates a lot of problems.

- Nausea, edema

- Bronchial secretions

- Urinary frequency

- Bladder distention

- Pulmonary edema, peripheral edema

- Catheters, medications and other treatments

If you do palliative dehydration what you're actually doing by decreasing the fluids, is creating a natural anesthesia for the central nervous system. The level of consciousness falls and the patient is not perceiving any suffering. It's an anesthesia.

Dehydration & Benefits

The normal part of dying includes the blood supply diverting from the digestive tract to the heart and brain. That reduced PO intake because of deteriorating level of consciousness. The patient is no longer interested in eating or drinking. They have a disorder in thirst perception and don't recognize that there is any thirst. If you're using fluids, then use less than one liter a day to avoid negative consequences.

When we limit hydration for a patient, it cuts down on urinary output and, therefore, there is less need for toileting. Limiting hydration also decreases gastric fluids so there is less nausea and vomiting. Secretions in the pulmonary system also decrease when hydration is limited. As a result, not as much suctioning needs to occur.

Physiological Changes Lead to Less Perception of Pain

A patient’s level of consciousness will go from lethargy to coma. There is an anesthesia effect because of ketone accumulation, and the body produces its own opioids or endorphins when it is in a state of dehydration. That acts as anesthesia as well so the patient is not experiencing any discomfort.

Patient-Specific Decisions

Every decision and every recommendation made for our patients must be patient-specific. Look at the set of circumstances. There really isn't any right or wrong answer when we are honoring their plan of care, honoring their advanced directive, and we've educated them. Then if they say, “No, that's not for me.” We know it’s an informed, educated decision.

Are we going to do this short-term or a defined trial where we try it for X number of days, weeks, or months and if the patient doesn't like it we are done? Is it going to be long-term? We can have informed refusal where the patient says, “Thanks, but no, thanks. If I want to eat, I am going to eat. We need to consider all of that.

Extubation

We discussed this earlier, but we know patients self-extubate. In 67% of patients who had an NG tube placed, they extubated themselves within two weeks of placement. It is estimated that 44% of patients with PEG self-extubate. We also know that aspiration pneumonia is still a possibility regardless of having a tube.

Accept or Refuse

Patients need to have an understanding of what the consequences of PEG, NGs, IV are. NGs are uncomfortable. It’s been reported that negative experiences with PEGs include intimacy issues with the patient’s partner and negative reactions from other individuals in the family and friends.

If a patient refuses and they are going to continue to eat even though there's going to be a shorter survival period, then that is their choice. As long as it's been an educated, informed decision on their part. We need to honor that. We may not like it but that has been their choice. No one is going to tell them what their quality of life should or should not be.

Some specific reasons for refusal of ANH are that the patient/love one is too old and frail to have it placed. The family may have a certain cultural belief. If they are refusing we can certainly work with the individual on strategies to minimize aspiration and we can refer them to palliative care.

Waiver of Liability

A particular source, the Consent, Refusal, and Waivers in Patient-Centered Dysphagia Care, discusses issues with waivers. The guide suggests that waivers are in violation of ASHA’s Code of Ethics, Principle 1 because with the waiver we have placed our professional interests above the interests of the patient.

Waivers don't hold up in court. The court will say that the patient was coerced into signing it or they didn’t understand what they were signing. Usually with the “didn't understand” scenario, the patient or family may not do this when they're in therapy but they'll wait until they're discharged. Then they know there's that waiver in the file cabinet at the nurse's station and if they sign it, they get what they want or their loved one will get what they want. So, the patient or family member says to the nurse, “You know what? I want to sign that paper. I want to eat what I want.” The nurse will get it out of the file cabinet, put it on the counter and the patient will sign it and walk away. So, they did it. They got what they wanted. But, there was no education and that's going to come back and haunt you. Families can't have it both ways. They can't say they want Mom to eat and drink and then be really upset when Mom died. They need to understand, if they sign that piece of paper, they need to know what the consequences could possibly be.

This is where your detailed note comes into play. If your facility is still using waivers, I don't like to witness them. But if your facility is still using them, you need to be very careful who is acting as a witness. In some states, if you work in that facility, you cannot witness that form. It's against the law because it looks like you're coercing them into signing this because, for example, you don't want to thicken their liquids or you don't want to puree their food. So, somebody else who is not associated with the facility witnesses the waiver.

Your detailed note is much better. Include who you talked to and what did you say. For example, “This is what we saw at the bedside of Sally that raised red flags. This is what we found in the swallow study that we did. These are the recommendations that came out of those two evaluations. This is the diet we believe is going to keep you safe. These are the strategies we believe will keep you safe. Based on what we saw in the modified, when we tried them, these are the possible consequences. If you choose to opt-out of the recommendations or choose not to agree to them….” Answer their questions, write down what questions and comments they had and what your responses were. That is going to be much better than just a signature on a piece of paper that said, “I want what I want.”

I was in an assisted living facility one time and was told that the family signed a waiver. When I went to the chart it was a torn piece of notebook paper that said, “Family wants the patient to be on a regular diet.” That is not even close to a waiver, it will not hold up in court. You have to be very careful.

The patient care meeting has a lot of documentation. Below are some possibilities that you might use if the family or the patient wants to continue to eat but they are a known aspirator.

- Pt. may benefit from comfort feeding plan with known risk of aspiration dependent on family decision regarding plan of care

- NPO vs. NPO with temporary ANH (alternative nutrition/hydration) for time limited trial vs. comfort plan with known risk of aspiration

- Pt. has chosen an oral feeding plan following education on risks and consequences despite being a known aspirator

You need to know in your facility if these statements are going to work in your state. Also, how does it work in your facility if the patient truly doesn't want this? I have a facility in my area that if you don't like your diet, they will let you do what you want. But you have to say, I'm going to be a do not resuscitate and enter hospice. Which I totally disagree with, but that is the corporate policy. You can have what you want, but now you're in hospice. I do think you have to kind of qualify.

A Process for Care Planning for Resident Choice

There is no question when surveyors come in and look at the form that you get with the Care Planning Process for Residential Choice that you've done your due diligence. You've talked to the patient, you've talked to the family, and you've found out what they would like. You're coming up with some resolution to honor their choices. It may be that you are going to identify five foods that they can handle that don't have to be actually blenderized or processed or minced. We will review that care plan as time passes and tweak things along the way. If you use this form, you don't need a waiver. It’s extremely detailed and covers all of your bases.

New Dining Practice Standards

Under these new standards, we want to discuss hospice or palliative care. We need to develop the plan because the patient's needs are going to be changing over time. Again, talk about the benefits and the burdens. They suggest doing a natural puree if a patient refuses ANH. When the patient wants to make risky choices, adjust that plan of care to minimize the risks. However, if the patient is competent, all decisions default to the patient.

Key Points

Everything we talked about is specific to the patient. It’s their choice; their decision. We're looking at that particular patient's circumstances. We're looking at their culture and any religious convictions because that may be part of the reason why they are either accepting or rejecting your decisions. If this person is not decisional, the advance directives should be in the chart if they have them.

Remember that the bedside evaluation and instrumental assessment are just one piece of the puzzle that we bring to the table. I've given you some decision-making tools to look at. Certainly, Dr. Planck’s is considered the most evidence-based.

We must consider the benefits and the burdens. It's very important when we talk to individuals that we give them information that they can read at their own pace. We talked about Hard Choices for Loving People in Part 1. That is a really good booklet that discusses benefits and burdens. Patient choices should be our standard practice of care. If patients can still make choices now then we need to honor that. If they can't, we need to honor what they have in writing in their advance directives.

Questions and Answers

I work at a skilled nursing facility and in situations where a patient is not safe for PO intake I've been encouraged for my legal protection to write a diet order that includes the safest diet for the patient, and then let the doctor override my order for no diet restrictions. What would you recommend in this situation?

What I would recommend is, based on what you believe will keep this patient safe, I would write that and then, talk to the patient and family. You need to talk to your doctor about other options that are available but based on the modified or the bedside evaluation this is what I'm really thinking is going to keep you safe. So, that certainly puts you in the position where you're saying this is the safest diet or the highest-level diet, or the least restrictive diet. Then if the doctor disagrees, he won't sign it. But I've had a lot of patients say once the doctor signed the order, they will go to the doctor and then he would change it based on that discussion that he had with the patient's family or the patient.

Can you just briefly summarize, again, the difference in benefits between PEG versus an NG tube for those patients with cancer.

If you go back and look at the slides, you're going to see some literature that says the PEG is better. You're going to see some that says the NG is better. So, it's not my decision, which one they get. I just need to tell the physician and the dietician that we're not doing well meeting our needs by mouth where it's unsafe and, bottom line whichever the doctor chooses to recommend, that's his choice. He has the bigger picture more than I do. So, he's going to be the decision-maker as far as which one.

Just to clarify is the poor prognostic indicator for PEG over the age of 60 or over the age of 75?

On that list of poor prognostic indicators, I believe it did say 75. But we've seen a lot in the literature that's talking anything over the age of 60, 65. Again that's just one consideration. The more things that are on that list, the worst idea it is.

One issue regarding recommendations and prognosticating regarding what keeps them safe is that we as SLPs often get it wrong. Do you care to comment on that?

We can talk about what we saw on the modified. That makes sense. But I've seen a lot of individuals with home health who have a modified that says nectar they have refused. We're working on strengthening their swallow but we have not seen a consequence given the fact that they're drinking thin. So sometimes, you know, we can be pushing nectar when there aren't any issues with this person. So, in that particular case, my method of approaching the patient is, “This is what we found in the modified and is why we're making that recommendation for nectar. I can't force you to do that. This is your choice. I do need to tell you what could happen if you don't follow these recommendations but if you choose to opt-out, I'm not the dysphagia police. So I can't force you to do that but we're going to work on these exercises and see if we can make that swallow better.”

References

1. Kate Krival, PhD, CCC-SLP; Anne McGrail, MS, CCC-SLP; and Lisa Kelchner, PhD, CCC-SLP, BRS-S, chair of the Education Committee of Special Interest Division 13 (Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders) of the American Speech-Language Hearing Association

2. ASPEN Nutrition Support Core Curriculum, 2007: 740-60

3. Shega, JW, Hougham, GW, Stocking CB & Sachs, GA. (2003) Barriers to limiting the practice of tube feeding in advanced dementia. J Palliative Care. 6(6):885-893.

4. Brett AS, Rosenberg JC. The adequacy of informed consent for placement of gastrostomy tubes. Arch Intern Med, 2001;161:745-748

5. Plonk, WM. (July 2005). To Peg or Not to Peg. Practical Gastroenterology 16-31.

6. Adapted from National Hospice Organization, 1996. Updated to reflect common current practices.

7.Hu I. Hauge T. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) for enteral nutrition in patients with stroke. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2003:9:962-966

8. Wijdicks EF, McMahon MM. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy after acute stroke complications and outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999:9:1099-111.)

9. Mitsumoto H, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in patients with ALS and bulbar dysfunction. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003; 4: 177-185.

10. Gillick MR. Rethinking the role of tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia. NEJM, 2000:342:206-210

11. Murry, J. (2007). Role of the SLP in the Care of the Medically Fragile Patient. Summit Meeting of Care for Patients at the End of Life: The Role of the Audiologist and Speech-Language Pathologist, ASHA Preconvention

12. Rabeneck, L, McCullough, L, Wray, N. Ethically justified, clinically comprehensive guidelines for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. The Lancet, 1997; 349-497.

13. Young, E.A., Perkins, H.S., & McCamish, M.A. 1992. Ethical dimensions and clinical decisions for parenteral nutrition: In dying as in living, In Rombeau, J.L. & Caldewell, M.D. (Eds.) Clinical nutrition: Parenteral nutrition (2nd ed), Orlando, FL; W.B. Saunders

14. Sharp H. (2007). Dysphagia: Paradigms for Ethical Decision-Making and Recommendations for Use of Life-Sustaining Treatment. Summit Meeting of Care for Patients at the End of Life: The Role of t he Audiologist and Speech-Language Pathologist, ASHA Preconvention.

15. Old, J. Swagerty, D. (2007). A Practical Guide to Palliative Care. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

16. ASPEN webinar: applications of ethical & legal concepts in use of nutritional support therapies, Charles Mueller, PhD, RD, CNSD and Albert Barrocas, MD, FACS. May 11, 2011) )

17. Rouseau, How fluid Deprivation Affects the Terminally Ill, RN: 54 (1), 73-76)

18. Kinzbrunner, BM. (2002). Nutritional Support and Parenteral Hydration. In N.J. Barry M. Kinzbrunner, 20 Common Problems in End of Life Care (pp.313-327). New York: McGraw-Hill.)

19. Sheiman S. MSN, RN, CS. “Tube Feeding the Demented Nursing Home Resident” Journal of American Geriatric Society, 44:1-2, 1996.)

20. ASHA.(2004).Guidelines for Speech-Language Pathologists Performing Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Studies. ASHA Supplement 24, pp.77-92

21. Post, LF, Blustein, J., Dubler, NN. 2007. Handbook for Health Care Ethics Committees. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD.

22. Pioneer Network. New Dining Practice Standards. Aug 2011

23. Ladislav Volicer, M. (2005). End of Life Care for People with Dementia. Alzheimer’s Association.)

24. Kenny, N., & Singh, S. A. (2015). Decision Making for Enteral Nutrition in Adult Patients with Dysphagia–A Guide for Health Care Professionals.

25. Yukawa, M., & Ritchie, C. S. (2015). Nutrition at the End of Life. In Handbook of Clinical Nutrition and Aging (pp. 303-312). Springer New York.

26. Cranford, R.E. Neurologic Syndromes and Prolonged Survival: When can Artificial Nutrition and Hydration be Foregone? Law, Medicine and Health Care. Vol 19:1-2, Spring, Summer 1991.

27. Arcand, M. (2015). End-of-life issues in advanced dementia Part 2: management of poor nutritional intake, dehydration, and pneumonia.Canadian Family Physician, 61(4), 337-341.

28. Orrevall, Y. (2015). Nutritional support at the end of life. Nutrition, 31(4), 615-616.

29. Moreschi, C., & Da Broi, U. (2015). Bioethical and Medico-legal Implications of Withdrawing Artificial Nutrition and Hydration from Adults in Critical Care.Diet and Nutrition in Critical Care, 1093-1106

30. Gallagher-Allred, C., O’Rawe, A.M. Nutrition and Hydration in Hospice Care, 1993. The Haworth Press, NY.

31. Qureshi, A. Z., Jenkins, R. M., & Thornhill, T. H. (2016). Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding during neurorehabilitation. Ifs, ands, or buts. Neurosciences, 21(1).

32. Sharp, H, Brady-Wagner, LC, Wagman-Bolster, AS. (2006). Speech-Language Pathology Services in End of Life Care Ethical, Clinical, and Legal Considerations, ASHA Rockville, MD.

33. Faigle, R., Bahouth, M. N., Urrutia, V. C., & Gottesman, R. F. (2016). Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Gastrostomy Tube Placement After Intracerebral Hemorrhage in the United States. Stroke, STROKEAHA-115

34. Day, L. W., Nazareth, M., Sewell, J. L., Williams, J. L., & Lieberman, D. A. (2015). Practice variation in PEG tube placement: trends and predictors among providers in the United States. Gastrointestinal endoscopy, 82(1), 37-45.

35. Jiang, Y. L., Ruberu, N., Liu, X. S., Xu, Y. H., Zhang, S. T., & Chan, D. K. (2015). Mortality Trend and Predictors of Mortality in Dysphagic Stroke Patients Postpercutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. Chinese medical journal, 128(10), 1331

36. Zelante, A., Sartori, S and Trevisani, L. Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy: Use and Abuse in Clinical Practice. Openventio publisher, Gastro open Journal, July 2015 Vol. 1, Issue 3.

37. Sprung CL, Maia P, Bülow HH, Ricou B, Armaginidis A, Baras M, Wennberg E, Reinhart K, Cohen SL, Fries DR, Nakos G, Thijs LG and The Ethicus Study Group (2007) The impact of religion on end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 33:1732–1739

38. Mitchell SL, Tetroe JM. Survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2000;55:M735-M739

39. Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Brody JA. Gastrostomy placement and mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA,1998;279:1973-1976)

40. Hong, J., Kim, D. K., Kang, S. H., & Seo, K. M. (2015). Clinical Factors of Enteral Tube Feeding in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 94(8), 595-601.

41. Aguila, E. J. T., Cua, I. H. Y., Fontanilla, J. A. C., Yabut, V. L. M., & Causing, M. F. P. (2020). Gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID‐19: Impact on nutrition practices. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 35(5), 800-805.

42. Preedy, V. R. (Ed.). (2019). Handbook of Nutrition and Diet in Palliative Care. CRC Press. Eating Related Distress in Terminally Ill Cancer patients and their family members by Koji Amano and Tatsuya Morita

43. Schwartz, Denise Baird, Mary Ellen Posthauer, and Julie O’Sullivan Maillet. "Advancing Nutrition and Dietetics Practice: Dealing With Ethical Issues of Nutrition and Hydration." Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2020).

44. Schwartz, Denise Baird, Mary Ellen Posthauer, and Julie O’Sullivan Maillet. "Advancing Nutrition and Dietetics Practice: Dealing With Ethical Issues of Nutrition and Hydration." Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2020).

45. De, Diana, and Carol Thomas. "Enhancing the decision-making process when considering artificial nutrition in advanced dementia care." International Journal of Palliative Nursing 25.5 (2019): 216-223.

46. Consent, Refusal, and Waivers in Patient-Centered Dysphagia Care: Using Law, Ethics, and Evidence to Guide Clinical Practice. Jennifer Horner,a Maria Modayil,b Laura Roche Chapman,a and An Dinha

Citation

Dougherty, D. (2021). Decision Making for Alternate Nutrition and Hydration - Part 2. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20440. Available from www.speechpathology.com