Introduction

I'm very excited to share some information with you about embedding intervention strategies into everyday routines and activities of infants and toddlers and their families. One of my lifelong passions has been to make learning meaningful and seamless for young children and their families who are receiving early intervention services. My retirement from FSU allows me the opportunity to pursue that passion and to be able to share with others the materials that we've developed over the course of 35-40 years. I started in this as a parent of an infant receiving early intervention services. So the tools and ideas that I'm going to share with you are both very personal to me and useful to you in the field.

At this point, because I'm retired, I'm able to share everything with you available through our website at fgrbi.com. You're gonna be hearing that from me many times throughout this presentation. We're gonna be spending some time looking specifically at three tools that will be helpful to you in your practice. This is a very practice-based presentation that will give you some ideas to use with all families to help them get a great start in development, particularly in communication development. Many of these tools and materials have been developed over the course of watching thousands of videos of early intervention providers during home visits and classroom-based visits in programs such as Early Head Start.

We're gonna be looking specifically at identifying tools that will help you engage the family in planning their own intervention and strategies that can be used easily within a variety of daily routines and activities.

Family Guided Routines Based Intervention and Caregiver Coaching

So let's talk about how we can embed intervention into the everyday routines and activities of the very diverse children and families that we serve using these three tools. Being a provider working in the field, and learning to coach caregivers maybe through mobile or tele-intervention services in addition to the various home-based practices that you've used, it's really helpful to have a framework. The framework that we use is the Family Guided Routines Based Intervention and Caregiver Coaching framework. FGRBI is certainly not new. It's been around since the 1980s and is an example of practice-based coaching. Practice-based coaching is where we are really looking at specific measurable and observable behaviors that are in tune with what caregivers need to learn and want to learn in order to interact with their children effectively. They're also congruent with the guiding principles of the Part C early intervention guidelines and programs that we see within each of our states. FGRBI has four components: family-guided, routines-based, functional-based outcomes, and evidence-based instruction. When we are teaching and coaching caregivers, we're using these four components. We will talk a little bit more about them shortly.

Our Goal is Building Family Capacity

Our coaching is focused on building caregiver capacity, which is a little bit different from some of the other coaching approaches. We use two sets of practices, the relational-based practices and participatory practices. Each of those practices contributes important information to our coaching process. These practices involve the ability to support caregiver learning and increasing their confidence. By increasing their confidence, we also increase their competence. This builds their self-efficacy and allows them to think about what they're doing, why they're doing it and to be able to generalize it to other skills. So we're really helping them to impact their child.

Our coaching and the tools that I'll be sharing with you have been developed to help you support the caregiver learn how to interact with and support their child's learning through a variety of routines and activities. I often hear from providers that they are concerned that families aren't engaged. They want to sit and observe, and then we hope that they try it out later. Or they may only participate a little bit. We're gonna be looking specifically at strategies that engage caregivers and give them the opportunity to practice with you during the visit.

Now, because of teletherapy or mobile coaching, caregivers are more engaged, except for some folks who may not be as comfortable and confident participating in teletherapy. But, again, these kinds of strategies are helpful. It's sort of that old adage if you give a man a fish, he's got a meal for a day, but if you give them the opportunity to learn how to fish, then they can support themselves. With caregivers, we want to give them tools they can use and expand upon to help improve child outcomes.

Embedding Defined

What is embedding and why is it important? We hear the word embedding, and we say we're embedding in routines and activities. But are we really? Let's break it down. One of the definitions says that when we're embedding, we're inserting. And yes, we are. In embedded intervention with caregivers, we're adding a strategy. We're inserting something for the caregiver to do in addition to what they would typically do in a routine or activity that supports the child's ability to practice a specific skill or outcome.

When we're embedding, we're inserting a specific intervention strategy that the caregiver is comfortable and confident in using, that doesn't interfere with the routine or activity, and that really helps the child be able to participate. We want to make sure that that strategy we've inserted is integral to the routine and the activity so that it fits in and is not contrived. We aren't adding additional toys or materials to a playset. We're not adding a toy to a snack routine. We're not bringing in something that the parent wouldn't typically do. We're using what they use and how they use it, but inserting a strategy in a way where it fits.

We're also making sure that it is enclosed closely so that it doesn't interrupt or interfere with the routine or activity. The caregiver and child are working closely as partners. We're always looking at that caregiver-child dyad so that they can achieve their outcome. These definitions really help us ensure that we're using everyday routines and activities that the caregivers have. We're doing the things that they would typically do. We're inserting a strategy the caregiver can learn to use or is using well, making it an integral part of the routine but not changing it radically. We want it to be easy and motivating for the caregiver to do frequently throughout the day.

Why Embed Intervention?

We embed so that we can teach new skills. Routines are familiar and comfortable. The family knows what to do and the child pretty much knows what's going to happen. So that's a great opportunity to add something new that the child can do or to increase their ability or capacity in the routine. So instead of just communicating with a grunt or a sound, they could be practicing a gesture, a combination of sounds, or a word. They could be expanding and asking questions as they develop new skills. We want to use the familiar at a time when it's functional and meaningful both to the child and the family. That helps us provide a comfortable foundation for the child and the parent to learn something new. We're not trying to overwhelm anybody. We're using what's there, what works, and adding something new.

Also, because the embedding is occurring naturally throughout the day, it provides more opportunities for practice not only with the one caregiver who may have been involved with you in the intervention but also with family and friends. It becomes functional. It becomes a part of what they do. It also enhances rather than adds to what a caregiver already does to the child. We're not trying to change what the caregiver does. If the caregiver is naturally good at labeling and is good at repeating what the child says and giving them another opportunity, perfect, let's use that. Let's add that to other routines as a natural strategy for the caregiver. Then maybe we need to encourage her by adding a little wait time. So we're not drastically changing.

We'll talk more about strategies, but I just want you to realize our goal in embedding intervention is not to change what's there but to use what's there and just change it only as much as we need to. The child, then, has a more active role. They're more participatory, and so is the caregiver, because they have something comfortable that they can do throughout the family activities. Rather than having separate therapy routines or activities, the child is participating in family activities across a wide range of things that can occur throughout the day.

What Families Need to Know About Embedding

What do families need to know about embedding? They probably don't need to the big, long definition that I gave you. But it is somewhat important for them to understand why they are being asked to embed. Do they know why it's so important? Do they understand that when they're embedding, they're really teaching their child? Do they understand that they're the one who's the best to use that skill because they're with their child the most, especially during all those everyday routines and activities? Embedding is helpful for the family to learn ways to support their child not only with you but to also come up with some of their own ideas that work.

Not only do we want families to know why embedding is important and why their role is important, but its also important that know what they are embedding? Sometimes in our therapy sessions, we assume that caregivers know things that we know just because we've talked about them. But we're not always as specific as we could be or in a way that can benefit parents. For example, when I work with some providers who are working on increasing language, or they want the child to use more words, that is very broad. I'm still trying to increase my language! What kind of language are we increasing? How do we get more specific? If we're increasing words, what words are we trying to increase during play with blocks? What are we trying to increase during hand-washing? What words are we trying to increase when we're going outside to the sandbox? What are the kinds of words we want to increase when I'm upset and I don't want to go the bed? What are those specific targets? And we call them targets so that caregivers understand these are the little steps to the big goal. Yes, we're increasing words. Yes, we're expanding language, but we're going to break it down to very small targets.

Then we want to address when and where we use these targets? What kind of routines are the most effective? It could bath time or playtime - whatever time works for the family. Next, we want to address what strategies they are supposed to use. Is this where I'm supposed to pause? Is this where I'm supposed to label? Again, help the caregivers know what it is they're doing and what are they embedding. That makes the difference.

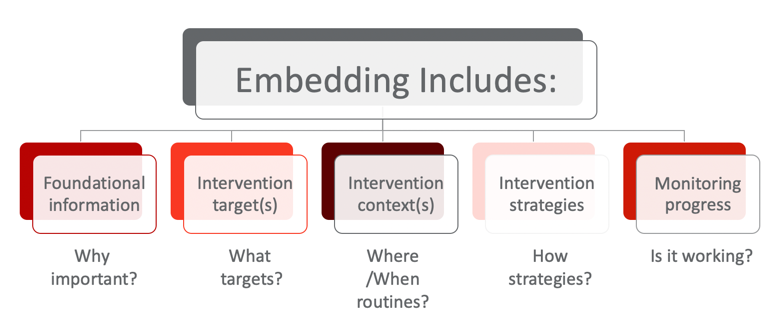

Finally, how do we know it's working? When caregivers can answer these five questions (Figure 1), then they're able to be able to embed more effectively. We are going to come back to these five-question concepts in a few seconds.

Figure 1. Embedding strategies.

Foundations of FGRBI Coaching

This is some of the basic foundational information for Family Guided Routines Based Intervention and Coaching. We are using adult learning, family capacity-building, and participatory practices that promote the caregiver as the person who is the best support their child's learning. We want to make sure that in our interventions, we are using observable, measurable practices so that we know what we're doing with parents works. Additionally, we also want to individualize those diverse and meaningful routines that are specific to the families. There's no one good routine for everybody. They are individualized.

We have to be open to using universal strategies that work in a variety of different routines and activities with children across their age span. We want to use coaching strategies that support that caregiver where they are. Some caregivers start off with a lot of strategies they already have in their back pocket. Others, unfortunately, are just getting started with this. They may be new parents. They may not have thought about their role as one who has to help support their child. It may not come naturally. But there are many great strategies that we can teach them.

The Family 5Q

The Family 5Q is our first too and it is a series of questions. They are actually the same five questions that we discussed earlier:

- What do parents need to know about embedding?

- What's the target they're gonna teach?

- When, where, and who's gonna teach it?

- How are they going to teach it?

- Why is it important for them to know how to do it?

We use the Family 5Q because it helps the caregiver remember what to do. Too often we're asking caregivers to remember lots and lots of things - something they could do during bath time, something they could do when playing with toys, etc.. What we want to do is to make the Family 5Q an easy way for caregivers to know that they're embedding their instruction. We want to make it intentional so that they can tell you what the 5Q is, and they know what they're working on. They know they can use it in different routines and activities. Sometimes our plans are just that: they're plans. They don't get to the point of becoming action. When we talk about the 5Q, we're talking about, how to make tasks intentional with lots of opportunities to practice. We use the Family 5Q throughout the session. We use it when we gather updates from the family, when we're planning what we're gonna do during the session, when we're in the middle of a routine, and we use it again as we finish up the session so that we the family feels confident with implementing the intervention between visits. It's not fancy, but it's very effective.

Now, we can take look at figure 1 and fill in the boxes for the family. For example:

- Why is it important? Well, we want Corey to be able to get attention. We want him to be able to greet and request. We want him to be able to use some of those early behavior regulation skills that will help him interact with others. That's really important to the family. They want him to communicate with a purpose.

- What are the targets? His targets are early gestures. We're starting right away with those early gestures so that he can wave to show everybody that he notices that they're there. He can reach for the things he wants or push away the ones he doesn't want. He can celebrate with us all of his cool skills. He can be clapping. Those are very specific gestures that are going to be used in specific routines. The caregivers are going to use specific strategies such as getting down face-to-face, using some imitation, expecting him to participate, maybe a little prompt, waiting for him to respond, and trying it again.

- How do they know that it's working? They will know when they see him using those gestures in the routines.

So, those are just a few examples of using the 5Q. Again, we fill it out very simply for the caregivers to be able to respond to it. It's just as simple as the caregiver being able to answer five questions.

SS-OO-PP-RR: Adult Learning and Family Guided Practices

Our second tool starts is called: SS-OO-PP-RR. That is the framework we use in our caregiver coaching and it stands for Setting the Stage, Observation and Opportunities to embed, Problem-solving and Planning, and Reflection and Review. These are practices that we believe are important for both home visiting as well as classroom visiting to make sure that the provider or the coach can support the caregiver's and the teacher's ability to feel confident with implementing the interventions and embedding them throughout the time between our visits. What really matters is what happens throughout the day. It's not about our visit. If we're an effective coach, then we are providing the best practices we can to help the caregivers continue the interventions throughout their day so that the child is learning while he's playing and while he's engaged with his family.

Setting the stage. When we are setting the stage, we're looking at building that relationship with the family. Finding out from the family what they do and what's happened since our last visit. We're setting them up to become the decision-maker. We're asking them, "How did it work? Was it working? Why is it important?" So, we're answering a couple of those 5Qs during this stage. We're also making a plan that includes the 5Qs so that the caregiver is making decisions about what's important to them, even before we start embedding intervention into the routines. We want to see what's happening and build on the caregiver's strengths. It gives us a chance to tell the caregiver what's working well, ask them what they like, what's working, what they think isn't going the way they want it to. Then, we can coach them in areas that they believe are really important and that will make a difference to them. We're going to be very intentional in our coaching. We are encouraging caregivers to be intentional in embedding opportunities throughout the day. And in return, we're going to be intentional in coaching them to use a variety of general and specific strategies so that they gain confidence and competence. Additionally, we're going to practice with them in a variety of different routines and activities to make sure they're feeling confident in their ability to do the things that we've practiced together and to generate new ideas.

Observation and opportunities. The purpose of observation and opportunities to embed is to, again, enhance the meaningful engagement with the caregiver during the routines and activities. This is important to really emphasize because in using SS-OO-PP-RR, we're trying to spend as much of our time as possible with the caregivers to build their capacity through participation, not just talking about it but actually doing it with the caregivers and practicing with them in routines and activities. Of course, all of that practice leads to problem-solving and planning because some things work and some things don't work as well as they could. And sometimes some things work so well we want to try it in another routine or with another target.

Problem-solving and planning. We want to find ways to grow the intervention through problem-solving and planning and helping the caregiver see how they can use their skills to figure out what to do if something doesn't work when we're not there.

Reflection and review. This, of course, leads us to reflection and review, where we start thinking about what made a strategy successful. What were the challenges? How can we look at enhancing this particular strategy or routine to help problems? How can we expand the opportunities for the child?

General and Specific Coaching Strategies

General Coaching

SS-OO-PP-RR has four components, but we're really going to take our time looking at the observation and opportunities to embed and focus on how we are intentionally coaching the caregiver. There are a variety of different coaching strategies that are used in early intervention and with school-aged children. There are even business and life-coaching types of opportunities. Some of these strategies are particularly useful for getting to know the family and building that relationship. We call those general coaching strategies where we are doing a lot of information exchange. As you well know, there's the importance of sharing information about child development, making sure you've shared information about the child's program, helping answer any questions that the families may have. Sometimes we're playing alongside and interacting with the caregiver as a partner and observing how things are going. Those are also considered to be general coaching strategies.

Specific Coaching

The other strategies that we use in coaching that are also evidence-based are specific strategies. Again, it's important to recognize in the literature that general coaching strategies are useful to enhance the relationship and support the caregiver in their understanding of their role and how important they are. But to help caregivers embed intervention, to get them engaged, and to practice with their child between visits, we're going to need to provide some specific coaching strategies.

The first one that we're going to be using is direct teaching or demonstration with narration. They're pretty much what they sound like - showing the family what the intervention strategy is, what it looks like, and how to do it with some explanation. We use direct teaching or demonstration to teach new skills, new strategies or a new situation. If there's something new going on, we want to make sure the caregiver knows what it is. But, it's not a lecture. It's giving that basic information. If they know what it is, it helps them to be able to do it. Then we can move on to strategies like guided practice, caregiver practice, and feedback. Other specific coaching strategies include problem-solving, reflection, and review. So these are strategies that are seen in the literature as having an effect in coaching caregivers.

What to Use When?

When do we use each of these strategies? As I said earlier, our general coaching strategies help support the caregiver relationship. We use general coaching to engage the caregiver and help them understand the importance of their role. General strategies are also used to support the caregiver interacting with their child overall, to balance and synchronize the pace of the caregiver and child interaction, and to make sure we're not trying to teach more than anyone can learn in one visit.

The specific coaching strategies are used to give the caregivers the opportunity to learn and practice with us, to learn to problem-solve, and to provide systematic teaching with feedback for the caregiver. Just as we make sure the child has plenty of practice to learn a new skill, we need to make sure the caregiver has plenty of practice to learn how to use a strategy within the routine. And remember that will vary greatly for different routines, as well as different caregivers and their knowledge and understanding of what they're working on in that moment. So it's important to provide enough time to really practice.

Observation

I want to spend a few minutes emphasizing the importance of observation. I know I have been emphasizing how important intentional practice is. But I want to make sure you understand that the first part of practice is observing. Step back and observe first before engaging with the caregiver. Find out what they're already doing. See how the caregiver and child as a dyad interact. Learn about their routine. Snack time doesn't look the same for every family, nor does hand-washing. I have been surprised at the number of different ways children and families play ball. One of my favorites was when the child sat at the top of the stairs and threw the ball down the stairs to the parent, and then the parent had to get the ball back up the stairs. I never saw anybody play ball like that before, but the opportunities in that ball-playing activity were huge. We had to make sure the ball went hard enough and fast enough, and we had to bounce it off the steps. We practiced different sounds for each of the "plop, plop, plops" down the steps.

When you know what the caregivers and children are already doing, you can be much more effective in guiding their practice. We also observe in order to learn how the caregiver engages the child. What do they do that really gets the child's attention? Do they have super facial expressions or lots of voice changes? Are they a caregiver who's a little bit quieter and sometimes uses a whisper to get attention? Maybe they use a soft, gentle touch? Is this a caregiver who uses a lot of directive strategies and not as many responsive strategies? I am not suggesting that one way is better than another, but we need to know where to start.

How can we observe and learn more about the child? What really interests the child because we know they are going to stick with it better if they really enjoy it. How independent are they? Are they given a lot of opportunities to be more independent or is some of it a bit preempted by the caregiver helping out?

Then we can learn about that child-caregiver dyad. Does the child get to initiate? Does the caregiver do more of the initiations? All of these things help us with that balance and setting the pace. When we learn more about the routine and the caregiver and child's interactions, we can decide which strategies to share. As options for the caregiver, we can look at building where they currently are. Maybe we don't even need to teach any new strategies because the caregiver's using a lot of them. At that point, we can focus on how to use the strategies in different routines or more frequently or with less support.

I encourage clinicians to observe each routine for at least 20 seconds before saying anything. Then you want to say something positive to the caregiver about what you saw them do that really supported the child. Again, we are trying to build their confidence in their interaction with their child and that the things they do really help teach the child.

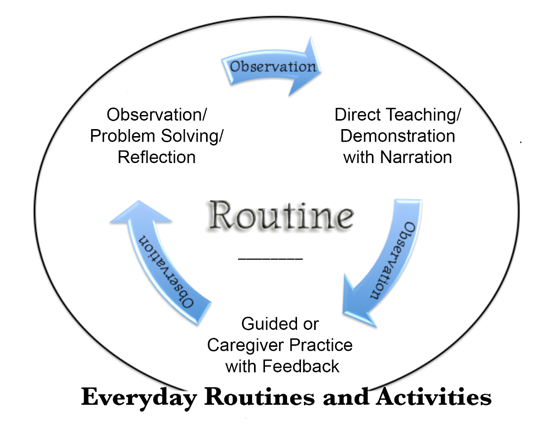

Teaching and Learning Cycle

You'll notice that observation is at the top of our teaching and learning cycle (Figure 2). Through observation, we can identify if there's a need for direct teaching and demonstration with narration. Consider my earlier example of the mom who already has a really good rate of response to the child. She allows the child to initiate. She responds. She waits a little bit, then encourages another initiation. You don't have to teach that balanced turn-taking to her because she already has it. But you could talk with her about where she could use it, and how she might be able to refine it.

Figure 2. Teaching and learning cycle.

You're going to guide the mom's practice and you are going to let her practice again. Then, you're going to observe and you may teach if it's necessary. Then you observe again. During that time that you're practicing with the caregiver, you may offer some additional suggestions or recommendations. You may pull back and watch the caregiver again and see how they're doing, and move to some problem-solving and reflection. Ask the caregiver, what do you think worked well? What would you do differently the next time? What felt right? What were some of the things that were challenging? Giving the caregiver the opportunity to analyze or use their metacognitive skills and their metalinguistic skills to work through what they were doing that really helped their child learn and was supportive within the routine.

We do not want to take over the routine and activities. If you are working on hand-washing, you, as the clinician, can't stay in the bathroom forever. These are opportunities for the caregiver to practice and problem-solve with you to see what works well and really enhances. Remember, the purpose of embedding is to insert and integrate and enhance the relationship for the caregiver and child. We use these teaching and learning cycles in every routine. Sometimes we go back if we need to provide more information. Sometimes we can skip a step and move on. But we use multiple teaching and learning cycles in multiple routines throughout each home visit so that the caregiver has had that ample time to practice. We really want the caregivers to have time to practice in a variety of routines so that they have time to problem-solve with you.

When we do interviews with families at the end of early intervention, I ask them what they thought helped them the most. What did the coach do that made them feel like they were, an active participant and helped them feel more confident? The number one answer is always, "They problem-solved with me. I didn't have to figure it out alone. I always felt that my ideas were valued. We figured out together what worked, what didn't work, and then during the week I could go back and try it again." There is this sense of feeling like a partner with the early intervention provider. The caregiver can have their own ideas. It fits in with what they want to do and that really builds capacity.

Our goal in coaching is building their capacity. Sometimes it takes longer to get there with families. That just means we need to make sure we're building a relationship, making sure we've spent enough time with teaching and demonstrating, and spending enough time guiding them to where they feel more confident. We start by asking some reflection questions that are a little easier to answer. We don't want them to feel as though we're asking them to figure out what to do without our support. It's about scaffolding for the caregivers to build their capacity.

Family Routines

We want to be sure that caregivers have enough opportunity to practice in a variety of routines. One of the things that I see so often on home visits and in the classroom, is the SLP's spending a lot of time with play. Play is critically important for child learning. Play is really the place for children to explore and to grow. And I agree that play is the work of young children. But play isn't the only thing the family does throughout the day.

We want to take a look at all the other activities and routines that caregivers do because we can embed so many different strategies to teach a wide variety of communication and developmental skills during routines like washing your hands, taking a bath, cleaning up the bathroom, doing the laundry, etc. There are so many caregiver routines that caregivers are engaged with their child. So let's embed and insert an opportunity there for practice.

We also want to encourage a wide variety of early literacy skills with books. I'm not big on apps, but sometimes there are some great apps for children to interact with their caregivers as long as they're interacting with their caregivers. Additionally, many families like the opportunities to have some kinds of writing and drawing activities as well as certain kinds of songs and rhymes that fit into their day. So, we want to explore how to use music to help support.

Finally, everyone has chores. I mentioned doing the laundry, feeding the pets, taking out the garbage, helping with the dishwasher, or putting the groceries away. There's always time to put toys away and to clean up the living room. Dusting and watering the plants are also great interactive activities. Plus, it gets the job done. Running errands is another activity where we can embed intervention to support the caregiver in being successful and not feeling as though it's one more thing to do and a potential for a crisis to occur.

Many of our communication outcomes can be embedded into routines and activities that actually support a positive interaction and social opportunities for the child and the caregiver. So think about how to expand beyond the living room floor, beyond center time in early care and education. How do we get into a variety of other routines that occur throughout the day and every day so we can get the frequency of practice to be at a high and strong level that's very consistent for learning to occur?

Evidence-Based Intervention Strategies

This brings us to our third tool. I know the information on the slide is very small, but all of the tools and materials, including videos are on the fgrbi.com website. Everything I have shared with you is there. If you download the document, you will see a series of intervention strategies that have been shown in the research to be effectively used by caregivers in embedded intervention. So these are tried-and-trued intervention strategies (Click here for intervention strategies).

We all have our favorite strategies. But are those go-to strategies always the ones that are most comfortable for parents? By having a lot of different kinds of intervention strategies available and you're comfortable with, you're able to work with the family to pick out what works best for them. They may have some different strategies that will be more beneficial to them and they are more comfortable with. And that is a better place to build their confidence. again, we're building their confidence and their competence so that they can continue to support their child throughout the week.

The most important strategies are listed at the bottom of the triangle (Click here for document). They are called responsive-universal learning strategies that we believe all caregivers should use throughout their day to help support their child's communication.

- Set predictable routine

- Close proximity

- Face-to-face position

- Caregiver-child engagement

- Provides interesting activity and objects

- Talk in context

- Follow child’s lead

- Maintain focus with child

- Respond contingently

- Repeat opportunities

- Take turns

- Offer meaningful roles

- Use child’s language level

- Positive interactions

- Enthusiastic and warm

- Change flexibly and thoughtfully

Do you do this with every family? We believe that these are truly universal learning strategies that you want to have in your toolkit for families. These are the "how" strategies of the 5Q that families are comfortable using.

Of course, we start with predictable routines. Do caregivers know what a routine is? Do they understand the importance of having a beginning and an ending and a clear sequence of steps so that it becomes so familiar to the child that they can introduce something new? Many families need to have a little brush-up on what is a routine, and why it is valuable.

Do you remind caregivers of the importance of face-to-face using facial expressions? We look at some of the new research literature on brain development, and we see just how important that close connection is. I do mean physically close and having that opportunity to learn those cues and signals from caregivers and from children.

We talk about following the child's lead. We see this often in play, but how do we help caregivers follow the child's lead in other kinds of routines and activities that might be a little bit more parent-directed? How do we help support the caregiver to not prevent opportunities for the child but actually encourage them?

Are we using interesting materials and objects for interventions? Are we making sure that they're objects and activities that the family would typically use? Do caregivers know how to take turns? Can they respond contingently? Does the child have a productive role? Do they have something important to do in every activity, even if it's simply carrying the spoons to the table to help set the table? Are they the person who pets the dog on the head or pats the dog while the food comes out? Maybe they could have a new role of helping to carry the food over. These productive roles in a routine can expand as the child becomes more independent, gets older and as the skills build. We want to think about different roles in every routine and activity that the child can assume so that they're doing more and the caregiver does less. And of course, we want to make sure that caregivers give the child chances to learn.

This triangle is our universal strategy tier for caregivers. We want to make sure the caregiver's comfortable with using strategies at the bottom of the triangle before we introduce strategies at that higher level of more therapeutic or individualized strategies. When the caregiver's comfortable with those, we can add one from the next tier until the caregiver becomes comfortable with those. We want to teach these strategies one at a time so that we aren't expecting caregivers to try and remember so much that it's too difficult to implement or feels contrived. We want it to be as seamless as possible for the family.

Strategy Matrix

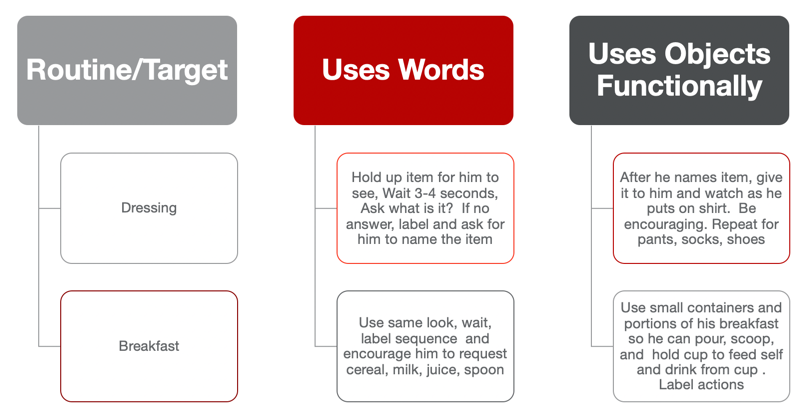

I am often asked how we help the family with the 5Q when we're gone? There are many different ways we can do that. But one of the things I like to do, again, is to keep it simple for the family. Maybe use a routine and strategy matrix (Figure 3).

Figure 3. routine and strategy matrix.

Pick a couple of routines that the caregiver is definitely going to work on. Families are great at identifying where it is the easiest for them or when they are most likely to embed the intervention and make sure that they can see that it's working. In this example, the caregiver identified getting dressed in the morning and having breakfast. The early morning was great for the caregiver because the other children had gone to school, and this was a really great way to start the day. The mom also shared she felt really good about the day because she knew she had been practicing with her child. Everything else she described as the "sprinkles on the doughnut"because they had been working together and practicing, and she had gotten in the groove of embedding. So she was able to continue to add opportunities throughout the day.

You may be looking at this and thinking, "This is not exactly rocket science." I couldn't agree more. But it does answer the 5Q - What are the words I'm gonna use? How am I going to do it? Where and when am I going to do it? And how will I know that it's working? So the caregiver has those steps ready to go.

I encourage you to go to the website (fgrbi.com) to find a whole series of videos that include Lexi with her twin toddlers, other young children who have multiple and significant needs, as well as children with hearing impairments. There is a wide range of kids with different types of disabilities, different family structures, and ways that SLPs and educators have used these tools to build the caregiver's capacity to embed intervention in everyday routines and activities.

Questions and Answers

How do I get started moving away from play to using a variety of different kinds of routines? I'm pretty used to playing during my visits.

That's a great question, and it's one I get asked a lot. I want to start by saying that I don't want you to think I'm telling you to not use play as one of the routines and activities. You certainly should. But as I'm sure you understand, there are a lot of other things that happen throughout the day. Play is one that fits into a variety of different times and places, but there is all that other stuff that happens throughout the day, too. So I think one of the first things that you can do is to observe. What is it that the caregiver was doing when you got there? What else is in the living room or the family room or the toy room, wherever it is that you're playing, or wherever you go to play that you could ask some questions about: "Does Johnny help you with this?" "How do you do that?" "What are some of the things you do out in the kitchen?" "Where is he when you're doing the laundry?" So, there are ways that you can sort of observe and see what's happening and gently ask some questions about that. So that's sort of the observational strategy. There's also the strategy that's just right up front and says, "You know, there are a lot of things that go on through the day. What are some things that you do that we could talk about embedding intervention in those?" And offer some suggestions.

Some clinicians even use the handout that I shared earlier on observation and opportunities, which is sort of a matrix of different kinds of routines that occur throughout the day. They will ask parents, "What are some things that he does with you for getting dressed?" Or "What are some of the things that he does with you when you're doing your chores?" Or "What does he do when you're cooking meals?" Sometimes families share there are some tough times: "Getting into the car seat is nothing but a hassle." Or "He really, really has a tough time puttin' the toys away and making a transition from one activity to another." Or "We'd like to see him be able to go outside and play with the rest of the family. What can we do?" So sometimes families have some things that they would really like to explore with you. But they're not sure that they should ask you those questions because you do play. So what comes first? Is it that we play, and that's what families think we do? Or is it that we're really not sure how to get out of play because that's what we do when we're with the families, and we don't know what else they do? So, again, think back to what's on the IFSP. What are the routines and activities that they talked about that were important to them?

Ask a few more questions. Do some observations. Listen carefully for things that aren't going so well. Just check in with the caregivers about some of the things that they do. Listen with that other set of ears when you're getting updates about the family spending more time out in the yard or going to the park or they tell you about grandma coming. These conversations tell you what is happening in the family's life. You can then begin to explore with the family some opportunities to join in, as well as those times that are not good for the family to embed interventions. If the morning routine is a very busy time for them, ask if there is another time during the day that might be better.

Moving away from play is really a collaborative process. Find out what the caregivers do and what they think would be great opportunities to involve their child with them or how they could embed some intervention in certain activities. Also, try to increase the diversity in types of routines so that the child is getting more practice throughout the day in functional times where learning can occur.

I am not sure how I feel about doing direct teaching or demonstration with narration as coaching strategies. That feels a little pushy to me. Is that a good family-centered practice?

I want to answer this by asking, "How do you like to learn? Do you ever need somebody to explain it to you so that you know what it is? What am I trying to learn to do here? What is it? How do I do it? Tell me about it. Do you ever find yourself asking other people to give you just the bare bones of, what it is that you need to do?" I bet you're gonna say yes to that. The other question that goes along with that is, "Do you learn sometimes by watching somebody do it and having them explain it to you?"

Sometimes hearing about it isn't good enough. I need to see it. That's what direct teaching and demonstration with narration are. I mentioned before, you don't bring in PowerPoint slides and tons of handouts when you visit the family. In fact, never give the parent the handout of evidence-based intervention strategies and tell them to read it and pick one out. That's just not it. We don't give them the handout and have them fill out the routines categories. Those are tools to help guide you to help find out information from families and to share information with families. You're trying to figure out how much information do they need to feel more comfortable to take that risk? We also use video examples to show parents what it looks like.

How do you do this without being rude? Well, it really comes down to how yo ask and how you provide the information to the parent that is important. We don't just hand it to them. I believe they want the information to be provided in a way that makes them feel like they are a partner with you. Sometimes it starts off with, "Have you ever tried..." or "Have you ever thought about using...? or "What do you think would happen if we did....?" Make it a conversation with an open-ended question, not putting them on the spot but saying, "Let's explore that together. Here's what I know, and here's what I've tried. Let's look at it. Let's talk about it. Then we're gonna practice it together."

Whenever we do demonstration with narration,that is modeling. But we're explaining it with the purpose of helping the caregiver and then do it themselves next. We provide guided practice where the caregiver tries and we offer some ideas and feedback to them while they're doing it. It's a sequence. I don't think you're being rude if you provide information in a way that's friendly and as a partner to the caregiver. If we are truly trying to help the caregiver build capacity, we have to give them the information that they need in order to be able to make informed decisions and to practice it. We don't want to withhold information, information is power. But, it is how we communicate information that will be important to the caregiver.

References

Please see handouts for a list of references.

Citation

Woods, J. (2020). Embedding Intervention Strategies into Everyday Activities of Infants/Toddlers and Their Families. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20407. Available at www.speechpathology.com