Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the course, “Helping Adolescents Navigate Mental Health and Social Thinking Challenges” presented by Sharon Baum, MA, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List 3 red flags indicating a mental health challenge or crisis in students with ASD.

- Describe at least 3 ways to work simultaneously on a mental health challenge and social thinking skills.

- List 2-3 ways to manage a mental health crisis an adolescent may be experiencing.

Introduction

Today, I will be discussing how we can better help adolescents navigate mental health and social thinking challenges. As a member of the NEST program for the last eight years, I have noticed over and over again that many of my students with ASD were also struggling with mental health challenges. My job became a collaboration with other professionals to figure out how to address both needs at the same time.

Mental Health Overview in Adolescence

I attended a Thrive New York City Mental Health Training back in 2018. I learned so much about adolescents and mental health, and now use strategies from that training with my individuals with ASD.

A mental health challenge is, "Anything that impacts a student's ability to live, laugh, and learn.” That seems very simple in nature, but when we think about our adolescents, they come to school as students who are trying to learn and live their lives. When there's something impacting this ability to learn and just enjoy life, then we have to dig deeper and figure out why. So, even though it's a simple statement, it's something that spoke volumes to me. I realized that many of my students were coming in with difficulties that were impacting their ability to simply learn and laugh with their peers.

Statistics

The statistics are staggering. In general, 20% of youth ages 13-18 experience severe mental disorders every year according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration Program (SAMHSA). What's even more staggering is that suicide was the second leading cause of death in 2016, ages 10-34, and since then has just grown. This is where we really have to come in because suicides are increasing, and sometimes we don't know when a student is on the verge of ending their life.

Another key statistic to think about with adolescents, and specifically students with ASD, is that one-half of all chronic mental health illnesses begin by age 14. That's a big deal because many of our students come in when they're maybe 11, some even 10, and it may not be apparent right away. Sometimes it evolves and develops over time.

A lot of parents over the years, especially parents of my students with ASD, have been concerned about their children withdrawing from them. I've had to tell a number of them, "You know what, don't worry about it because this is typical adolescent behavior. They don't want you so involved in their lives anymore. They don't necessarily even want me that involved all the time." I've had parents say, "They're talking to you, but they're not talking to me. Why are they being so private?" That's natural, that's common and that's just something that they experience as they navigate their adolescence.

However, when there's extreme privacy and withdrawal from everyone that is a call for concern. When people feel like individuals are becoming very private and are not sharing anything about their lives with anybody else, that is a call for concern. Additionally, while adolescents are at higher risk, clearly those with development disorders including ASD and intellectual disabilities are at an even greater risk.

Approximately 70% of the autistic population has at least one, if not multiple, co-occurring mental health issues (Roux and Kern’s, 2006). This only increases with age. We see this emerging in adolescence and if we don't address it, it could become bigger and bigger. This is why we have to keep in mind that there may be mental health issues going on and it may not be one, it may be multiple mental health issues.

Gender

Gender is an important factor to consider. Working in the NEST program, over the past several years many of us would ask each other, "Where are the girls? Where are they?" We were wondering what's going on with not seeing females in our program. Is it because they're not being diagnosed as much? Is there less prevalence among girls? Are girls just not as likely to develop autism? As time evolved and we started reading the literature more, we noticed that girls actually do have autism, it may not be as often as boys, but it does appear. Girls seem to know how to hide it better. Girls are trying to blend in more and therefore they may appear shy and reserved. So, we may miss it.

A lot of times girls develop eating disorders and anxiety disorders because they're trying so hard to fit in. I think the media is actually a big part of the issue because the media is a little biased towards women in the autism world. Typically casting the “Sheldon's” of the Big Bang Theory - the nerdy, single guys who are still living at home - the media doesn’t often take into account the girls that are present. That really impacts our notion and maybe even creates a bias with diagnosis.

Recently, girls are being diagnosed more frequently and the ASHA Leader has an article called "Invisible Girls" which mentions that the internalizing can lead to anxiety.

Girls are more likely to blend in and there is a new TV show about girls who developed into adults and found out they had autism. So, the media is changing its bias a little bit, which is good news for females with ASD.

Social Challenge vs. Mental Health Challenge

Our goal, as SLPs, is to improve social thinking and pragmatic language skills. In order to do that, we have to differentiate between a social thinking challenge and a mental health challenge. Of course, it is possible for the two to exist together. However, our intuition and experience as an SLP can guide us in recognizing the difference between the two.

It’s important to understand that sometimes it may appear that a student is struggling with mental health because they're isolated, withdrawn, and not engaging with their peers. They may be having meltdowns that are causing sadness. But, those behaviors could be part of a social thinking challenge in which they have difficulty engaging with their peers and making friends. By using tools, such as questionnaires, we can get inventories of our students at the beginning of the year to look for patterns. Those patterns can help us determine if the student is experiencing a mental health challenge or a social challenge. The questionnaires at the beginning of the year are key because they give us ideas about patterns and trigger events that can cause problems and then help determine solutions.

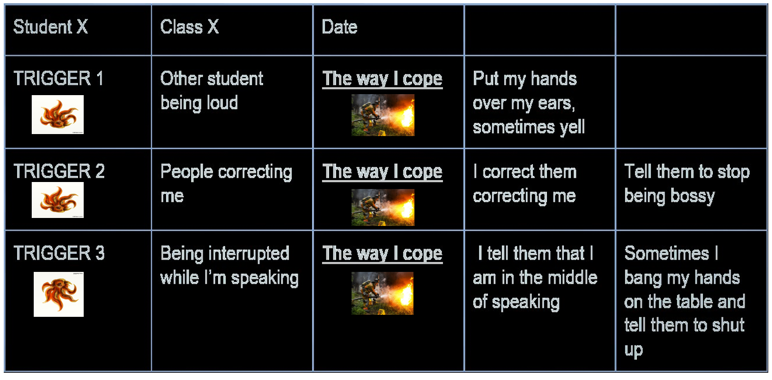

Example of Trigger-Solution Visual

Here is a visual that has helped me. I came up with it with my students to help them figure out the triggers and coping mechanisms that they're using. This helps me understand each individual student better.

Figure 1. Triggers and coping mechanisms.

I use this visual to individualize the triggers and determine if there are specific ones that are occurring repeatedly. I also want to figure out if there are sensory challenges that are occurring over and over again. If so, we are going to work through them. Of course, it doesn't mean there is a mental health challenge if the person reacts to the trigger. However, if this reaction continues over a period of time it can lead to a mental health challenge.

Be mindful that challenges and triggers will change based on the context. Adolescent students with ASD are not exposed to every situation possible, so as the context changes, their triggers change as well. The example in figure 1 shows that one of the student’s triggers was another student being loud. The student coped with the trigger by putting their hands over their ears and sometimes yelling. Sometimes the yelling turned into screaming, which turned into getting really angry.

The second trigger for this same student occurs when someone corrects them. He stated that he copes by correcting them in return and telling them to stop being bossy.

The third trigger for this student is being interrupted while he is speaking. He copes with this by telling them that he was in the middle of speaking or sometimes putting his hands on the table and telling them to shut up. This is just one example, but this table has helped guide me through this with many students.

However, it is a collaboration process because many of our students are not necessarily aware of what their triggers are. They have trouble with problem-solving and figuring out what the problem was that led to the reaction. This is a tool that we can use to help them, but we have to actually guide them through it to figure it out.

Comorbid Challenges with ASD

The term "co-morbidity" is basically when two disorders occur at the same time. This happens with ASD often and again, we have to ask ourselves if ASD is causing the mental health challenges or if the mental health challenges were already there? According to the National Institute of Mental Health, the leading federal agency for research on mental health challenges, the most common comorbid challenges are:

- Irritability

- Hyperactivity

- Suicidal thoughts

- Anxiety: social isolation (Roux and Kern, 2016, Drexel University)

- Depression

- PTSD

- OCD more common: differentiate between repetitive interests

I want to highlight anxiety for a moment because social isolation seems to be at the very core of this anxiety that is tied to our students because many of them are dealing with social isolation due to the challenges that they have. Social isolation can lead to anxiety because of this lack of connection with others.

OCD is also more common, however, be mindful that OCD can be mistaken in our students for their repetitive interests. We don't want to label a student as having OCD because they're very interested in legos or technology or trains. At the end of the day, we want to harness those strengths and interests, not beat them down in a way that we feel is harming them. We don't want it to think or say, "Oh this is a repetitive interest and therefore the person has OCD."

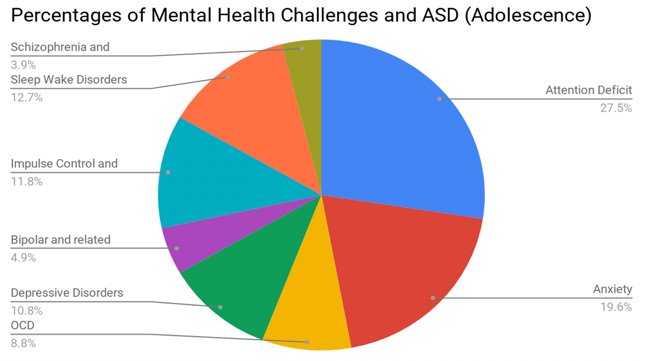

Figure 2 is a chart that breaks up Erdman's recent research of other co-morbid challenges.

Figure 2. Percentages of mental health challenges and ASD (adolescence).

You will notice that attention deficit and anxiety have the highest percentages for occurrence with ASD. We all know that anxiety comes in many different forms because of the ASD. Also, with ADD, I've had students over the years who were diagnosed with ASD but the ADD was taking the forefront in terms of their participation in the speech groups. They had difficulty attending to the task and therefore it looked like they're socially isolated or not engaged. Oftentimes, this behavior can look like ASD, so it's important to consider if the ADD is getting confused with ASD. Very often we do see it together. Additionally, students with ASD often have social thinking challenges and ADD, so we have to be mindful of each specific student.

Trauma/PTSD and ASD

Trauma is an area that I've been investigating more recently because it can affect any adolescent based on a prior experience that they've had. It is expressed differently in students with ASD compared to students who do not have ASD. Typically, in my speech groups, adolescents without ASD do not shy away from showing their reactions. Very often, the triggers are known because of prior experience. For example, if their father was murdered it could be that death or reading anything about homicides immediately triggers them. If somebody's talking about their parents they might get triggered. It's kind of an automatic understanding that they will be triggered in that moment. Whereas individuals with ASD may not react in the moment and can even have a delayed reaction. Recently, I had a student who lost their dad a few years ago and they were reading A Long Walk To Water which is about refugees escaping from their country. That was a trigger for him but we didn't know any of that because he wasn’t showing any signs in school. This was something that he had brought up to his mom and then his mom had to relay it to us.

Additionally, our students are vulnerable to being ostracized and teased because of the ASD. Because they're more vulnerable much of time, bullying over time can lead to trauma. Trauma can also be caused by years of treatment and constantly hearing what they are doing wrong. Over time that can build up and cause trauma.

There's actually a great group on Facebook called Trauma Informed Schools that works with students with ASD or adolescents, in general. They have discussed how many of these individuals get treatments that are not necessarily beneficial to them and over time it could lead to trauma. For example, ABA treatment has recently garnered some of that backlash. Cooperstein, in 2018, wrote an article explaining that there are many individuals with ABA treatment that have experienced some trauma and really didn't benefit as much as they would've liked. Again, it's controversial and some studies prove its efficacy.

Even though there's no treatment for both trauma and ASD, we can think about both when treating the individual. Later, I will discuss some strategies that incorporate mental health in a positive way so that we're not just targeting social thinking but trauma and other mental health issues as well.

We also need to know the history of our students in order to address ASD and trauma, as well as understand the difference between females and males. In fact, Golan had said that at times it seems that girls are the orphans of the ASD world and this isolation can potentially cause further trauma. I wrote an article for the ASHA Leader about mental health and adolescents in 2018. One of the things I mentioned was using our SLP knowledge because we're the communication experts. We can really pick up on shifts in communication in our speech sessions.

For example, is the ASD student who has trouble monitoring verbal interruptions now showing a reserved nature? I had a student once who was really outgoing, loud, and interrupted others and we had to constantly tell him to think about others' perspectives and how they're feeling. But then he became reserved. It took a few weeks to notice this shift and reserved nature where he was no longer initiating. When we spoke to his mom, she indicated that there were a lot of life changes. It turned out that he was slowly developing a form of depression. So, we can be very vigilant about that.

The opposite can also happen in the communication shift. For example, the ASD student who is normally not initiating is suddenly very engaging, animated, and sometimes talking about things you never knew he/she was interested in. That could also be a sign that something's gone awry.

Sometimes we may see that generating inferences and other cognitive goals that the student was doing well in have worsened. For example, a student who is easily generating inferences is not completely challenged by the thought of making a basic inference even as it applies to their life such as wearing shorts on a snowy day. We may wonder what is happening. Any change in communication for a long period of time can be alarming and make us think about collaborating with others to see if this is a mental health issue.

Obviously, a student who's having frequent crying spells, anger outbursts, etc. need to be closely monitored. We know that our students can have meltdowns, but if it is becoming a more common situation, then we have to be vigilant about that. We also need to be vigilant about noticing transitions and big changes in the individual’s life because they can be excruciating for our students and can lead to mental health challenges.

The below figure explains how important it is to work with students collaboratively.

Figure 3. Collaboration model.

Trust is a key factor when working with any student. Often my students with ASD will say, "You just don't get it," or "You just don't understand." Very often they may not even trust us. By working on getting to know them, working on their strengths and interests, showing that we support them, and we're empathetic towards them, we can actually develop trust. If we view it as a team effort, after building that trust, we can move on to the next phase of accountability.

Accountability means that we are being accountable for each other and making sure that they understand what they're working on and what I'm working on in our speech groups. We are both aware of that accountability and how important it is for them if they want to make progress. For example, if their end goal is to work on their social thinking so that they can make friends despite any mental health challenges they may have, then they are being held accountable by going to speech therapy and working on activities that help them make friends.

Next is commitment where both parties are committed to the practice at hand and committed to working through conflict. If commitment continues, then the student moves to achieving results. Again, I believe that approaching this in a collaborative, rather than authoritative way, has really served my students well. Working together towards results is so much better than telling them what to do and how to fix things.

Empathy is key. Students with ASD especially feel that they are not being heard and so many times students have said to me, "You know we feel like our teacher doesn't get it." They just don't understand what's difficult for us." Some of them have said that they keep hearing the same mantra of, "Oh you can do it, you can do it. You can get better at this."

Some things not to say that really can affect the student negatively is to say, "Oh just ignore it," because then we are minimizing things for them. Again, over time they feel like many things have been minimized for them so we don't want to add to that. We don’t want to say, “I get what you're through." Not only do we not understand exactly what they might be going through, but it’s turning it back on us. We want to make it about them. Saying things like, “You’ll get over it” or “You just have to deal with it” minimize their issues and many students have actually shared that with me.

Again, these are points that I have absorbed from the Mental Health Thrive New York City presentation and feel they are important to share because our students with ASD feel that sometimes we just don't get it.

False promises are never good for anyone in our life. It's not good to do with our friends or family. However, giving false promises to someone with ASD is going to exacerbate the issue at hand. They're literal thinkers, so promising them that everything is going to be okay can really work against us because they may take it literally. Then when everything is not okay in the next couple of weeks, they may come to us and be really upset.

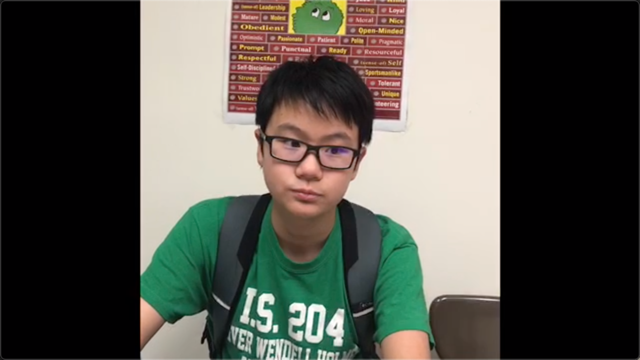

I interviewed a 7th-grade student who has been in our NEST program since last year. NEST is basically a collaborative program designed to help students with ASD develop their social thinking. By doing that, they can then better access the curriculum.

Barry Prizant is the author of Uniquely Human. He mentions that one of the key involvements in the treatment of individuals with ASD is that people are advocating all the time now. It's not just Temple Grandon advocating, we now have blogs from people who are advocating and professional development meetings where people with ASD are advocating for what they need. I want to share a video of an individual with ASD presenting on what he thinks is important for helping students with ASD deal with mental health challenges.

There are a couple of key points about the video. Spencer actually said it best at the end when he said that we have to focus on the individual. When dealing with social thinking and mental health with our students with ASD, we have to consider the individual and not the group because one individual with ASD is going to be different than another individual with ASD even if they're both dealing with mental health struggles.

Spencer also mentioned patterns. Patterns come in the form of observation. We have to observe the student at the beginning of the year to figure out what their patterns are and what their triggers are so that we can differentiate instruction. Spencer mentioned having two friends, one who is very outgoing and one who keeps to himself and is easily triggered by others. His two friends have completely different profiles. If we think about how they're doing in terms of mental health, we have to examine them from different profiles. One friend is engaging and helping many times when he doesn't know how to help. I actually know this individual personally and sometimes when he tries to help it isn’t received well because he doesn't know how to do it yet. He’s not at that level of social engagement where he understands how to administer that kind of help.

The other point is that we have to learn to accommodate the needs of individuals. Spencer mentions that accommodations have allowed him and his friends to really thrive. We are the collaborators, the language specialists, who can help with this. We have a duty to really work with professionals and/or teachers so that students get the accommodations that will lead to positive mental health. As Spencer said, it's thinking about the baseline and the patterns after the baseline. Then figuring out how this individual is doing?

Hidden Rules that Can Mitigate Negative Mental Health Responses

Hidden rules are a big part of our social thinking world because they are social rules that prevent us from doing things like bursting into a room when we know a meeting is in progress to talk about what we had for dinner. Hidden rules guide us on a day-to-day basis to know how to approach someone without making them feel uncomfortable. It's also knowing that when other people are speaking, we probably should try to bring in something that's related to what they're talking about or they feel like we don't care about their thoughts. These rules don't come naturally to our students but can exacerbate their mental health struggles because adolescence is a time of friendship.

Many of my students will say, "Oh you know, I don't really care about making friends." I don't really believe that because over the years I've seen time and time again, the students who say they don't want friends will then seek out friends. And it’s not always in the most productive way, but they will try to form connections with other people as part of the process. We want to encourage that but we also want them to understand what friendship is because a lot of times adolescence is a time when even students without ASD don't know what a true friend is.

Because of this hidden rule challenge, our students are at an even greater loss for true friendships at times. Over time, I have created individual hidden rules that guide friendship. Again, these are based on individual profiles and individual needs. For example, I've had students tell me that they are friends with people who I find out are taking their lunch every day. They aren’t stealing it, they will just say, "Hey dude, I want your lunch." The student is giving them their lunch or their snacks daily. When I ask them, "Do they give you something back?" They say, "No, they're my friend."

This eventually leads to a discussion about give and take because after a while it becomes exhausting when a person is giving all they can to this person that seems like their friend. That's where we can come in as social thinking specialists and say, "If someone wants to be your friend, they will not just take things from you without giving you anything in return." That's not something that's automatically going to be understood by them, it will take time.

Another thing I have seen is students with ASD can be very trusting and may even be bullied. I have said, "If someone wants to be your friend, they'll not join in when others are making fun of you, even if they weren't the ones to initiate it." Many of my students do believe that they have true friends and those true friends will sometimes join in with others. They don't understand the concept of how joining in and teasing could be a form of bullying.

If they're experiencing these negative interactions socially on a consistent basis, it can contribute to their negative responses. Someone who wants to be your friend will usually stand up for you. This gets into the issue of bystanders and a lot of my students don’t really understand what a bystander is. Yes, we want them to advocate for themselves, but if they do have a friend, that person will typically stand up for them when they are having difficulties and not necessarily just watch them be hurt.

Another reason this is so important is that a lot of my students have been bullied in the past. Again, this is a vulnerable population. Some of my students were bullied in elementary school and they come here and tell me about those experiences in our speech group. Very often this poorly modeled social behavior becomes reproduced. Meaning, some of the students with ASD who were bullied before are now bullying others who are a little more vulnerable than them. It becomes a poor social model that we have to keep in mind because ultimately that's going to affect the mental health of the person that they're bullying. We have to help them work through that trauma of being bullied in the past so that they understand the connection between a good social model and a bad one.

Another thing that we can use is mindfulness. Mindfulness is quite the buzz word but it is something that can really ground our students. In our speech groups, it may be difficult to do mindfulness because you're not going to spend a whole session on it. Some students may even roll their eyes at you. I have used an app called Headspace to help some students ground themselves. If we're doing an activity it's something that we can do at the beginning of the session for five minutes or maybe at the end of the session for certain groups. It really just depends on your students.

Something I've been doing research on recently and I think is excellent for our students is trauma-sensitive yoga by David Emerson. I've included yoga in the past with students in our social thinking groups. They would work on the yoga moves collaboratively. We take turns switching roles in terms of who's the leader and who's going to be following. It was great to have these different roles and shift them. Trauma-sensitive yoga is even more powerful. Students are so used to being told what not to do. They're always being told, "Don't do this. Don't sit like that. Show that you're actively listening with your body. Look in the eyes." This basically takes away the authority and says, "You know what, do what you want with your body." Instead of just being told what to do, you can now connect with your body. It's actually called interoception. Interoception is the idea of feeling what's in your body. What’s the sensation, why you're moving, and labeling it from an emotional standpoint. This is great for our students because it teaches emotional regulation and connectedness of emotion to body language, labeling feelings, understanding triggers, problem-solving, etc. This can really be a domino effect to target both social thinking and mental health.

Our therapy sessions are probably the hardest time of the day for students. They are in our room sometimes for 30-45 minutes depending on the speech session and this is the most taxing time of their day because they're forced to do the very thing that challenges them the most - social engagement. Even in stations in the class, they don't necessarily have to engage with their classmates the whole time.

Again, this is something that we need to think about. How are we going to take that pressure off because this is a very pressurized environment for them? Over time that can cause an escalation of feelings that are affecting their mental health in a negative way.

I've mentioned this already but keeping things fun is really important especially when someone is struggling with mental health. As we're catering to our students' strengths and interests, we are trying to include fun in our social engagement to help motivate them. There are different types of fun, obviously, and it was something that Susan Brennan, a NEST consultant of mine, had discussed with me. There is fun that is just for the purpose of having fun but it can also be completing a goal. For example, a lot of my students have long-term projects that they're working on together and it's hard getting through that process. When they're done, they are so happy they accomplished it.

I also had a group who took months to finish a movie because it involved creating a script and assigning character roles. It involved using props and creating the actual video. In the moment, there were a lot of problems. There was a lot of problem-solving and conflict to overcome. But in the end, they had fun because it was all for a common goal. When they were done, they were just ecstatic.

There's a third type of fun which my students don't really like but can make for a funny story after. I think keeping a sense of humor is key when dealing with our students that are struggling with both social thinking and mental health. I know a lot of specialists will say that we shouldn't use sarcasm because our students don't get it, but I've had a different experience. A lot of my students actually do enjoy sarcasm. We definitely have to know our audience, the individual, and their patterns but some of them really can totally shift from being in a bad mood to a good mood by simply making them smile with a little sarcasm. So, keeping a sense of humor is important.

Another important point is to make sure that we're centering the treatment around them. Make sure that the treatment is capitalizing on their strengths and interests. We want to make sure that they are helping us guide the session rather than us telling them what to do. As I said before, in so many of their other classes they are being told what to do and how to do it. Therefore, it is important for them to share their stories when they are with us even if it goes off course. Any time we have a student who’s able to share their life and culture, even if it's interrupting the movement of our session, that's a layer of trust that we're building because now there's a safe place where they're able to share their viewpoints and their knowledge. It's very helpful.

I have found a behavior management system to be very ineffective with my students if I’m trying to motivate someone who's not motivated. Students who are dealing with both social thinking and mental health challenges are not going to necessarily respond to a behavior system. This is where I've delved into creating a purpose for my students because it’s something that can't be taken away from them. It's not like, "Oh here is what you get in return for doing this.” It's bigger than that. It's intangible, but it's bigger than that. For example, some of my students have loved peer mentoring. I had a student who was very depressed and wasn't really speaking with his friends anymore. His depression got really bad, but once I gave him that peer mentoring role, he was able to mentor other students. He was so animated and I really think it was one of the contributing factors that got him out of his depression. I also had a student I called my “tech guy” because every time I had a tech issue, I called him. That was his purpose, he was the tech person.

Some of the students have created props for activities we were doing and they were great at it. That was a role that really gave them a purpose. That purpose can drive motivation even through mental health issues.

Identifying a Crisis and Collaborating

A crisis is different than a challenge. A mental health challenge is something that is going to interrupt the student. A crisis is something that we have to think about on a more critical level because someone's life could be in jeopardy.

This is where we have to take off our SLP hats and think purely about collaboration. If death is coming up frequently in the conversations, that could be an issue. If sleeping patterns are clearly off and the person is not sleeping at all or sleeping too much, that could be a sign. Drugs and alcohol use at an adolescent age is definitely going to be a red flag. If they're talking about harming themselves or harming others, this needs to be treated as an emergency. We have to immediately speak to the counselor and principal and discuss an action plan in which 9-1-1 is typically called, the parents are called, and the student then needs to get assessed by an outside professional.

In a crisis situation, we always have to speak to the guidance counselor or school psychologist if there are any red flags. You always have to speak to the parents because they may be hesitant in the beginning. However, persistence is key. I've had parents that we have talked to repeatedly about an issue their child is having and we are really worried about them. Some parents can seem unresponsive and sometimes after much persistence with them, it clicks. Does it always click? No, but we have to still continue with that. Remember that different people can improvise with different input.

We have to include the perspectives and input from professionals inside and outside of the school building. Outside counselors can share red flags that maybe we don't really see.

Case Study

This case study is similar to a student on my caseload. This is a 7th-grade male, age 13, who has a diagnosis of autism. He's been very quiet during SLP sessions. His typical profile reflects a student that is very interactive with peers, has trouble monitoring speaking time and allowing others to change the topic when it's centered away from his own interests.

For the past few weeks, he has not been initiating conversation at all. When asked questions he often says, "I don't know." He often interrupts conversations with random comments related to death and then remains quiet for the rest of the session. A friend of the student has explained that his mother just got a new boyfriend and that he despises this person. It has been reported by a teacher that his 15-year-old stepsister, who's been living in London with his father, has just returned home.

What do you do first? What are some obstacles to helping this adolescent? How may you collaboratively overcome these obstacles?

The team’s observations of this situation indicated that there's a suspected mental health struggle. The student shifted from being interactive to being socially withdrawn and now consumed with death. Both of which are red flags. Also, there has been a major life shift, and for any adolescent, transitions are hard but they can be especially brutal for those with ASD.

After thinking about all of these components, we decided that we were going to speak to the student because if we speak to the student first, we're not breaking their trust. “Action A” is always about assessing harm. We have to make sure that he wasn't hurting himself, hurting others, or in jeopardy of doing so. Then we spoke to the social worker and guidance counselor. In the end, we convened with the parents and discussed the changes and transitions that were affecting the child. We shared his preoccupation with death, the isolation, and the complete change in patterns socially. Those factors were leading us to believe there was a real mental health struggle.

The parents weren't fully on board with us in that they didn’t want to get ongoing therapy. That was a bit challenging, so we added counseling to his IEP and have continued to monitor the situation to avoid a crisis because we were almost in crisis mode. However, we avoided that by addressing it early on and dealing with it effectively as a group.

Questions and Answers

What was the name of the show that you mentioned, you mentioned an ABC show at the beginning?

It’s called Love on the Spectrum. It showed footage of females that were going out in the dating world as adults.

You mentioned some questionnaires. Have you developed these yourself or can you share where you found them?

It's a combination of both and I can share a couple of those. One of the things that I used was basically the chart that I showed with the trigger and how a student copes with those triggers. Basically, it’s a simple problem solving visual where we worked together to identify the triggers and they come up with the ways they cope.

How do you decipher social isolation from a lack of interest in socializing with others?

Typically, many of the students with ASD that I see appear to have a lack of interest of socializing with others. But when I get to the nitty-gritty, a lot of them actually do want social engagement. They just may not be going about it in the right way. So, they very often may present as having a lack of interest but really, they're just engaging in a way that is maybe not so productive. Social isolation, however, is different because the students who are experiencing social isolation will not often engage. They may have engaged at one point, but now they're not engaging with their peers at all. Whether it be negative or positive. They're just kind of keeping to themselves, staying very private, not really speaking up much, and people can't really get them to elaborate on anything in a conversation.

You mentioned that empathy is key, but what about the students who emphatically insist that making and keeping friends don't matter to them? Maybe they're saying people are dumb or rude, or I don't need friends, or things like that.

Almost every day, I hear a student say, "I don't need friends” or “I don't care about friends." Because I work in social groups, I always remind them that we are not forcing them to make friends. I come at it from a perspective of, "You know what, we're not forcing you to make friends. We just want you to be able to engage with peers so that you can work with groups effectively in the classroom and then ultimately work with groups in the workforce and things like that. We're not forcing you to make friends. If that's not your goal, that's not our goal either.” So, I come at it from that standpoint. Then, what happens is as the student gets better at working in a group, they start branching out and making friends from that situation. That kind of leads me to my original premise that many of them actually do want friends.

Citation

Baum, S. (2020). Helping Adolescents Navigate Mental Health and Social Thinking Challenges. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20380. Retrieved from www.speechpathology.com