Introduction

This course will cover desensitization activities for school-aged children who stutter. Stuttering is a complex disorder to understand. One of the reasons is because not all aspects of the disorder can be observed. As speech-language pathologists, we are trained in what to look for and what to listen for when it comes to communication disorders. We're trained to determine if a child is producing sounds incorrectly or if a child is stringing enough words together for their age. However, we receive considerably less training in how to uncover the child's thoughts and feelings related to their communication disorder and how those thoughts and feelings have an impact on the child and their ability to make success in their treatment. This course will focus on specific activities that can be used to identify and reduce the negative reactions that a child may experience as a result of stuttering. However, this course will not cover strategies for increasing fluency or for modifying stuttering moments.

One of the reasons that desensitization activities are such an integral part of the treatment plan is that, by reducing the negative reactions to stuttering the client is more likely to make progress related to other aspects of the disorder like the frequency and severity of their stuttering. There is a quote by Van Riper, one of the pioneers in the field, that I think does a great job of capturing the importance of desensitization activities. In 1973 he stated, "Since the fears, avoidance and struggle which characterize advanced stuttering stem from its unpleasantness, an unpleasantness which tends to grow stronger, no therapy can hope for success unless it seeks directly to reduce it." Desensitization to stuttering, or in Van Riper's words, “reducing the unpleasantness of stuttering,” must occur in order to make change and must be ongoing in order to maintain those changes.

I encourage you to supplement this course with articles and texts from other speech-language pathologists such as Scott Yaruss and Bill Murphy who have done a lot of great work in developing and researching the desensitization activities that will be reviewing here. Some of those articles and texts can be found in the reference section at the end of this course.

What is Desensitization?

What exactly is desensitization and what are we desensitizing to? Stuttering is experienced as a loss of control in a moment in time where the child knows the word that they want to say and has probably said that word many times before. But in that particular moment the word is not coming out in the way that the child intended or the way that the child expected. It is that unpredictability that differentiates stuttering from so many other communication disorders.

The child doesn't know if they're going to stutter, they don't know when they're going to stutter. And while they're stuttering they don't know how long that stuttering moment is going to last. Often what a child does is try to regain control by tensing up their muscles or by avoiding that word or situation all together. They might decide to switch to a word they feel they have more control over. They might stall by pretending to think or pretending that they can't find the word. Those reactions often have a greater impact on them than if they had just stuttered. Desensitization activities aim to reduce their reactivity to that feeling of loss of control so that they're free to make choices that are beneficial to communication.

Desensitization activities work by exposing the child to their fears, starting in comfortable and supportive environments and working their way up to situations that they perceive are more difficult for them. As they face their fears, their reaction to that fearful stimulus begins to diminish. Then their physical tension and struggle begins to diminish and they're more likely to say words or enter into situations that they previously avoided.

Why Should We Consider a Child’s Negative Reactions to Stuttering?

The World Health Organization's ICF framework stands for The International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health, and is a classification system for all health and health-related conditions. Whereas the ICD-10 classifies conditions by their etiology, the ICF framework looks at how the impairment affects a person's functioning.

Based on the work done by Yaruss in 1998 and Yaruss and Quesal in 2004 & 2006, if we apply the ICF framework to stuttering, the impairment in body function is the observable stuttering behaviors. Those are the repetitions, prolongations and blocks as well as the physical tension such as the eye blinks and/or tension around their lips. Environmental factors refer to how the people in the person’s environment respond to their stuttering. How do their parents respond to their stuttering? How does their teacher or their peers respond to their stuttering?

The framework also includes activity limitations and participation restrictions. Those are the limitations in the child's ability to perform certain activities or engage in certain life roles. For example, how does stuttering impact their ability to make friends? How does stuttering impact their ability to raise their hand in class? How does stuttering impact their ability to order food at a restaurant?

Finally, the framework describes personal reactions as the child's thoughts, feelings and response to their stuttering moments. Does the child experience feelings of shame or embarrassment? Does the child think that they can't present in class because they're going to feel too embarrassed or because their classmates might tease them? Has the child begun to develop avoidance behaviors like word switching or inserting filler words like “um” or “uh” in order to hide their stuttering moments? These are all personal reactions. Throughout the course, I will refer to reducing reactivity which is referring to all of these reactions.

The reason for including the ICF framework is because it does a great job of depicting how a person's reactions are a significant part of the impairment. It’s important to note that according to the framework, not only can a child's observable stuttering behaviors affect their thoughts and feelings about their stuttering but it also can work in the other direction. Meaning, the person's reactions to their stuttering can also affect their impairment and body function. ASHA has recognized the World Health Organization's ICF framework and has included it in its scope of practice. Therefore, we absolutely must assess and treat the person's impairment in body function, as well as assess and treat their reactions to their communication disorder.

Desensitization Activities

I am going to describe several desensitization activities that can be implemented in treatment sessions. I will discuss how to do the activity, the rationale for including that activity in the treatment plan and ways to make it more fun for the child. However, I can't stress enough that you should not assume that all activities will benefit all clients on your caseload who stutter. You have to take into consideration the rapport that you have with the child at that time, their comfort in talking about stuttering and what their current reactions are to stuttering before deciding if that particular treatment activity is appropriate for the child.

Treatment Activity #1: Creating Hierarchies

We are trying to challenge our children and “push” them outside of their comfort zone, but we have to do that in a gradual and a systematic way. Therefore, I want to start by introducing fear hierarchies.

What are fear hierarchies? Fear hierarchies are lists of speaking situations, beginning with speaking situations that occur in comfortable and supportive environments and then increases in perceived difficulty. It is possible that in the child's lower feared situations they also happen to stutter less. But the purpose of fear hierarchies is not to rank situations by how often the child stutters in them but rather rank situations by how comfortable that child is speaking regardless of whether or not they stutter.

I like to start by having the child list all the speaking situations they typically engage in in a typical week or a typical day. Then, I have them put those speaking situations into their fear hierarchies. Some examples of speaking situations include, speaking one-on-one with a family member, speaking with the entire family at dinner time, making a phone call, ordering food at a restaurant, calling out information in a group conversation, speaking in a loud room, raising their hand to answer a question, reading out loud or giving a presentation. The idea is to vary the number of listeners, their relationship with the listener and the dynamics of the environment. I try not to give the child examples at the beginning because I think it's really telling when the child comes up with their own speaking situations. It tells me a little bit about what they are and what they aren't worrying about. However, once they get stuck, I do give them some examples.

How does this aid in desensitization and progress? The purpose of creating fear hierarchies is to guide the gradual exposure of the child to situations in which they anticipate will be difficult. In essence, the fear hierarchies will guide the other activities that will be discussed later. The hierarchies also help to ensure that I am starting in situations that the child feels comfortable in and then starts to work through situations that they perceive is more difficult.

Creating fear hierarchies also allows for increased child ownership over developing assignments. So as they're coming up with home challenges, the child can refer back to the fear hierarchies and decide on their own where they're going to try out a certain skill. Also fear hierarchies encourage a new way of defining success. Instead of only defining success by how fluent the child is or how often they use a specific strategy, creating fear hierarchies demonstrates to the child that we can also define success by the risks that they take; by identifying situations that are difficult for them and doing them anyway.

Creating fear hierarchies can make a child feel vulnerable. It might be the first time that they're admitting out loud that there are certain situations that are hard for them or there are certain situations that they are avoiding. It is important to be patient. At first, the hierarchies might be short and they might be vague, but as the child gets more comfortable talking to about stuttering, they can make adjustments to the hierarchy.

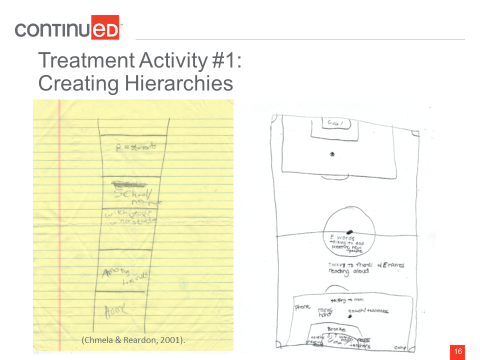

How can I make this fun? One way to introduce fear hierarchies is to draw analogies between the stuttering and the child's interests. For example, if a child really likes basketball, have the child draw or print out a basketball court. On the basketball court, have them show where it's very easy for them to make a shot. Then in that area of the basketball court, have them start listing some situations that they feel are easy for them to talk in. Then have them show on the court where it's difficult to make a shot, and that is where they can put some of the more difficult speaking situations. Figure 1 shows some examples of fear hierarchies that my clients have created.

Figure 1. Examples of fear hierarchies.

The picture on the left is a ladder that the child drew. At the bottom of the ladder they put the situations that they perceive as being rather easy and that they'll still speak in even if they stutter. So for this particular child, speaking at home and speaking among friends feels the easiest. Then he worked his way up the ladder to the top which is speaking at restaurants and ordering food at restaurants. This is a great example of a child who is not very comfortable talking about things that are difficult for him. This example is a bit vague. However, over time, as he got more comfortable, we were able to add to the ladder and make it more specific to him.

The picture on the right is another example of a fear hierarchy. This child was very interested in soccer, so he drew a soccer field. In the area very close to the goal he put situations that he felt were easy to talk in. As he moved away from the goal, he put situations that were more difficult for him. The furthest away from the goal, he put talking to new people and “E” words because he developed a fear of words that start with “E” and had started to avoid them. This activity was a great opportunity for me to learn some of his feared words, feared sounds and feared situations just by completing this fear hierarchy.

Treatment Activity #2: Stuttering Facts

What do you mean by “Stuttering Facts”? The second treatment activity has to do with building a child's knowledge of stuttering. There are a lot of facts that can be useful for the child to know about stuttering. That might include teaching them about the parts of the body that help us to talk (i.e., the speech mechanism). It can include talking about what stuttering is, what it's not and what causes it. We can talk about the different types of stuttering; the repetitions, the prolongations, the blocks. We can talk about the different choices that we can make when we stutter. That includes stuttering strategies and terminology that goes with those. Additionally, children really enjoy learning about different famous people who stutter. Finally, we can talk to them about why we're doing each activity to help them with the buy-in.

With younger children, I really enjoy letting them come up with their own terminology that's meaningful for them. For example, one child felt like his repetitions sounded like hiccups, so he would refer to his repetitions as hiccups stuttering. I also like to have visuals. For example, when a child is talking about their repetitions or their hiccup stuttering, I might have a picture of a bumpy road. If the child is talking about prolongations I might have a picture of a stretched out rubber band. I might have a picture of the speech mechanism, so that if the child is having trouble explaining something, he might be able to show or explain it by pointing to the part of the body where he feels the word is stuck or where he's feeling tension. It gives the child that extra support in being able to explain themselves.

How does this aid in desensitization and progress? The purpose of teaching children about stuttering is to reduce that fear of the unknown. We are giving them the tools to express their feelings, to explain their experiences and to ask questions about things that they don't understand or that they're worried about.

We're also working on reducing their fear of initiating conversations about stuttering and answering questions that their peers might ask them. We're showing them that talking about stuttering is okay and it's not something that we need to hide.

How can I make this fun? There are a number of fun ways that you can teach kids about stuttering. One way is to create jeopardy or trivia games. A link to an online free template for Jeopardy is: https://jeopardylabs.com/. You can add all of the stuttering facts into the Jeopardy game or have the children create their own Jeopardy game in the same way. They can also create brochures or handouts with the information that they learn. They can make presentations by taking on the role of being an expert on their talking or on their stuttering.

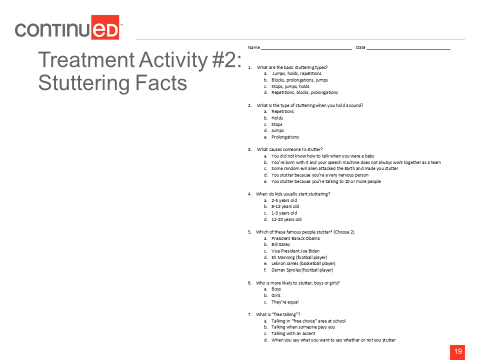

Figure 2 shows some examples of what one of my clients did with the stuttering facts that he learned.

Figure 2. Example of a stuttering facts activity (Click here for larger version of Figure 2).

This particular client, as he learns new facts he put it into a quiz that he created. The quiz has questions about the different stuttering types, the causes of stuttering and even one on famous people who stutter. Eventually, he gave this quiz to family members and some close friends.