From the Desk of Ann Kummer

Many speech-language pathologists report that, in working with children with speech sound disorders, they can achieve correct placement fairly easily. However, it takes a long time before the child begins to use the sound in everyday connected speech. Perhaps this problem can be improved with a more thorough understanding of the principles of motor learning.

Motor learning is a complex process that occurs in the brain in response to learning to perform a new motor sequence. Practice is a key component of motor learning. The motor skill or sequence must be repeated (e.g., practiced) until it can be performed consistently without conscious thought.

Motor learning is needed to acquire all motor skills, such as playing a musical instrument, dancing, and playing sports. In the same way, it is needed to learn to produce speech sounds correctly. It is common knowledge that the more the individual practices a motor movement, the more proficient he/she will be in performing that skill and in a shorter amount of time. Therefore, therapy must be designed to achieve the largest number of correct productions possible in each session. Practice at home is also very important, even if the practice is limited to a few minutes each day.

I am a strong believer in the importance of intensive practice when possible, and frequent short practice sessions throughout the week in order to achieve carryover in the shortest amount of time. Therefore, I’m thrilled that Dr. Carol Koch submitted this article about the principles of motor learning and the importance of using these principles in speech therapy.

Carol Koch, EdD, CCC-SLP is a Professor at Samford University. Much of her clinical work has been in early intervention, with a focus on children with autism spectrum disorder and children with severe speech sound disorders, including childhood apraxia of speech. Her research and teaching interests have also encompassed early phonological development, speech sound disorders, and CAS. She has been honored as an ASHA Fellow and is a Board-Certified Specialist in Child Language. Recently, Dr. Koch published a textbook, Clinical Management of Speech Sound Disorders: A Case-Based Approach. She is also a co-author of the Contrast Cues for Speech and Literacy and the “Box of” set of cues for articulation therapy and the Box of /ɹ/ Facilitating Contexts and Screener through Bjorem Speech Publications.

This is a very interesting and important article for all speech-language pathologists who work with speech sound disorders.

Now…read on, learn, and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA, 2017 ASHA Honors

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Ann Kummer CEU articles at www.speechpathology.com/20Q

20Q: Principles of Motor Learning and Intervention for Speech Sound Disorders

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Explain the principles of motor learning relevant to speech sound disorders

- Provide knowledge of results and knowledge of performance feedback

- Apply the principles of motor learning to speech sound intervention

1. What are the principles of motor learning and why are they important?

As the traditional or motor-based approaches for the treatment of speech sound disorders specifically focus on the motor aspects of sound production, a basic understanding of motor learning is beneficial. The traditional approach emphasizes the teaching of the placement of the articulators and the motor movement patterns needed for speech sound production. Therefore, speech sound production is a motor-based skill.

Motor learning is a “set of processes associated with practice or experience leading to relatively permanent changes in the capability for movement” (Schmidt & Lee, 2005, p. 302). A learned motor skill results from two different levels of performance that are demonstrated during the acquisition and learning phase and the retention and transfer phase. During the acquisition and learning phase, motor performance is demonstrated through the establishment of the ability to execute the specific motor skill. This perspective emphasizes that acquisition is the product of practice. Retention and transfer reflect the level of learning that is considered the permanent change in the ability to demonstrate the skilled movements as measured by retention of the skill after the training and practice have been completed. The level of performance during the practice phase of motor learning does not predict retention and transfer of the skill (Maas et al., 2008).

Motor-based approaches have a long history in the treatment of speech sound disorders, yet the research is limited regarding the principles of motor learning and speech-motor learning. Maas and colleagues (2008) have examined the application of the basic principles with intact motor systems. This research can be applied to traditional motor-based interventions with children who demonstrate speech sound disorders.

Maas and colleagues (2008) have emphasized three areas of study in motor learning principles in which evidence supports the application to the intervention of speech sound disorders in children. The three areas are pertinent to the conditions of practice and include prepractice, principles of practice, and principles of feedback. It is important to utilize this structure in the implementation of motor-based articulation intervention.

Further, the principles of motor learning are applied differently depending on where the child’s articulation skills are along a continuum of motor skills development from acquisition to retention. Application of the principles of motor learning to speech production offers promising insight into optimizing treatment (Maas et al., 2014).

2. What motor learning principles are relevant to speech sound production and speech sound disorders?

While motor learning principles have not been extensively researched as applied to speech motor learning, evidence of their application can be found throughout scholarly resources addressing speech sound intervention. Research outside of our discipline provides evidence of the basic principles of motor learning that may be applied to intervention for children with speech sound disorders (Maas et al., 2008). Future research in extending the principles to speech motor learning may serve to further validate the motor-based or traditional approach for the intervention of speech sound disorders.

Motor learning principles related to the conditions and the structure of practice and those related to the nature of feedback are the most relevant to speech sound disorders and intervention. Motor learning principles associated with the conditions of practice include practice schedule, practice amount, practice variability, attentional focus, and target complexity. The motor learning principles associated with the nature of feedback include feedback type, feedback frequency, feedback timing, and feedback control (Bislick et al., 2012; Maas et al., 2008).

3. Explain the motor-learning principle of pre-practice.

In the area of motor learning, pre-practice refers to areas of consideration prior to beginning practice that can facilitate optimal outcomes (Bernthal et al., 2013; Maas et al., 2008; Yorkston, Beukelman et al., 2010). Prepractice activities are designed to prepare the learner for the therapy session (Schmidt & Lee, 2005). Important considerations for prepractice are motivation to learn, an understanding of the task, and level of stimulability for sound production errors (Maas et al., 2008).

Motivation can be enhanced by ensuring that the learner understands that therapy activities are designed to improve speech intelligibility and reduce communication breakdowns. Selection of functionally relevant targets (family names, favorite activities) with input from the learner may also increase motivation. Making sure the learner understands the task through offering an appropriate level of instruction (consider language skills), cues, and modeling is also useful for promoting motivation.

4. Explain the motor learning principles of practice conditions related to practice amount.

Learning any motor skills requires practice (Schmidt & Lee, 2005). Therapy must therefore provide adequate practice to learn the targeted behavior. The options for practice amount include a small number of practice trials or sessions or a large number of practice trials or sessions. What we know anecdotally is that the learner must have maximum opportunity to practice correct production of the target sounds. Therefore, the focus is on creating a sufficient number of production trials each session to facilitate the acquisition and retention of new skills. This can be accomplished by emphasizing production practice and minimizing the time spent providing reinforcements. The literature for nonspeech tasks suggests that small amounts of practice are beneficial for acquisition but that variability and larger amounts of practice are associated with improved retention of skills. Currently, there is no empirical evidence regarding speech practice amount with respect to speech motor learning.

5. Explain motor learning principle of practice conditions related to practice distribution.

The next principle of practice consideration is how practice should be planned and distributed. Massed practice involves practicing targets many times over a short period with a shorter time between sessions. Distributed practice refers to how a set amount of therapy practice is distributed over time, with more time between sessions. Maas and colleagues (2008) propose that many shorter treatment sessions produce a better outcome than fewer longer sessions. Massed practice versus distributed practice may also have implications for motor learning. Massed practice appears to promote motor performance, the accuracy of speech sound production, or speech sound acquisition. Whereas distributed practice has been shown to support retention and transfer, which implies that motor learning has resulted in a permanent change in a skill (Maas et al., 2005). It is also unknown of the impact of practice amount on the effectiveness of massed versus distributed practice.

6. Explain the motor learning principle for practice conditions of practice variability.

Practice variability refers to the variations in phonetic or motor sequences used as stimuli. Constant practice involves practicing the same target within the same context. For example, sessions that focus on the production of the phoneme /s/ in the initial word position. Variable practice involves practice on different sounds in different contexts. For example, sessions that focus on the phonemes /k, g, s, z/ in the initial word position and the final word position.

There is some evidence to support that constant practice is beneficial in early practice during the acquisition phase. Further, that motor learning appears to be promoted with words that have different movement sequences, different co-articulatory contexts, and different manners of production across the phoneme sequences (Maas et al., 2008; Yorkston et al., 2010).

7. What is the practice condition of practice schedule?

Practice schedule refers to either blocked or random practice. Blocked practice involves repeated production of the same stimuli during sessions or treatment phases. For example, treatment sessions that focus on production of /s/ before progressing to production of /z/. Random practice involves different targets practiced during the same session or phases of intervention. For example, a session that focuses on production practice of /f, v/. Maas and colleagues (2008) also propose that random presentation of stimuli or targets promotes the development of motor learning better than blocked practice. Therefore, research evidence suggests that random practice is more effective at facilitating motor learning, which results in production accuracy that is maintained in conversational speech.

8. Explain the practice condition related to attentional focus.

Attentional focus can be viewed as being either internal or external. Internal attentional focus is related to the focus on articulatory movements, such as a place of articulation. External attentional focus refers to the outcome or the effects of the movements, the acoustic signal, and the sound the child produces. The effect of attentional focus on motor learning for speech has not been explored. However, in the nonspeech motor domain, it appears that an external focus supports and promotes more automatic movement patterns and greater retention/learning of the skill than an internal focus (Maas et al., 2008).

9. What is the practice condition of target complexity?

Target complexity or movement complexity refers to the sounds and sound sequences selected for intervention targets. Simple targets are those target words that contain earlier acquired sounds and simple word shapes, such as plosives and CV syllables/words. Complex targets are target words that contain the more difficult, later emerging speech sounds and sound sequences, such as fricatives and CCVC words.

Emerging evidence suggests that complex movement patterns promote learning of simpler movement patterns, but the reverse can not be supported by evidence. Therefore, it appears that targeting more complex items may be more efficient than targeting less complex items.

10. Explain the motor learning principles related to type of feedback.

Feedback allows the speech-language pathologist to provide information about the client’s performance. This type of augmented feedback has been shown to be effective in the facilitation of motor learning related to speech sound intervention (Schmidt & Lee, 2005; Wulf & Shea, 2004). Different types of augmented feedback have also been studied. Knowledge of results (KR) type of feedback provides information about whether the production was correct or incorrect. The clinician may say, “You produced the correct sound” or “That was good”. Knowledge of performance (KP) feedback provides more specific information about the nature of the production. The feedback addresses specifically what was correct or incorrect about the positioning of the articulators, the movement, or the manner of production.

For example, for a correct production, the clinician may say, “I really like how you made that sound in the back of your mouth”. Alternately, for an incorrect production, the clinician might offer feedback such as, “That was a good try, but let’s try again with your tongue behind your teeth”. Knowledge of performance may be more beneficial during the speech sound acquisition stage when the child has not yet established an internal representation of the target sound (Newell et al., 1990). The specific performance feedback provides the client with more information about the nature of the production. For an inaccurate production, knowledge of performance feedback guides the client to the specific aspect of the production to be changed in order to achieve accurate production of the target. Knowledge of performance feedback facilitates performance during the acquisition stage of speech sound intervention. Conversely, feedback that reflects knowledge of results requires the child to determine the nature of the specific error. Maas et al. (2008) suggest that once the target skill is established, the nature of the feedback should change from knowledge of performance to knowledge of results. Thus, knowledge of results augmented feedback leads to enhanced retention/transfer of motor learning.

11. What are some additional examples of “knowledge of results” feedback?

Knowledge of results type of feedback focuses on the accuracy of the production. Here are a few examples:

- “Great job!”

- “That sounded great!”

- “I heard you make the /f/ sound in that word!”

12. What are some additional examples of “knowledge of performance” feedback?

Knowledge of performance type of feedback reflects specific information about how the child produced the target sound. Here are a few examples:

- “I really like how you kept your tongue behind your teeth for the /s/ sound.”

- “Great job using your top teeth on your bottom lip to make the /f/ sound.”

- “I heard you change from the /t/ to the /k/ sound when you said 'car'.”

13. Explain the principles of motor learning for how feedback is provided, specifically related to feedback frequency.

How feedback is provided is another consideration. Feedback frequency refers to how often feedback is provided. High-frequency feedback is given after every attempt at the production of the elicited target. Low-frequency feedback is provided after some, but not all, attempts at the production of the elicited target. During treatment sessions, clinicians may adjust feedback frequency according to a variety of schedules, such as providing feedback on 80%, 50%, 20%, or 0% of trials. It appears that high-frequency feedback is beneficial during the acquisition stage of speech-motor learning. Evidence from current practice suggests that quickly reducing the frequency of feedback may be more effective in facilitating the retention or transfer of speech-motor learning. Infrequent feedback provides the child the opportunity to monitor and evaluate their own performance (Lowe & Buckwald, 2017; Maas et al., 2008).

The impact of feedback frequency may also depend on other factors. Research evidence suggests that practice variability, attentional focus, complexity, and the learner’s skill level and ability to self-monitor or self-evaluate interact with feedback frequency and produce different results.

14. Explain the principle of motor learning related to the timing of feedback.

The timing of feedback may also be a factor in motor speech learning (Bankson et al., 2013; Maas et al., 2008). Feedback may be either immediate or delayed. Feedback that is delivered with a slight delay may provide the client with the opportunity to self-evaluate the production. As previously stated, self-evaluation of speech sound production prior to augmented feedback may more effectively facilitate speech-motor learning. Feedback timing and the impact on performance may also be affected by attentional focus. A learner who struggles with awareness of articulatory placement may require immediate feedback that reflects knowledge of performance. Likewise, a learner who struggles with monitoring speech output may also require a higher frequency of immediate feedback since a delayed feedback situation may not result in self-evaluation of performance.

15. How do you choose stimuli following principles of motor learning?

This certainly is a complex question. And truthfully, there is no one “correct” answer. Clinicians must assess each client to determine which combination of practice conditions and how feedback is provided are optimal for that client. However, motor learning principles certainly can guide and inform these decisions. In addition, factors such as functionality or relevance of stimuli, stimulability, and target complexity are important considerations in intervention planning and the selection of intervention targets.

16. Are there stages or phases to intervention based on the principles of motor learning?

The facilitation of motor learning may follow a number of theoretical models that explain the process of speech-motor learning. Initially, the learner is introduced to the new skill, a new pattern of skilled movement that results in the correct production of a speech sound. Verbal instructions, demonstrations, and modeling are important elements in assisting the learner in producing the target sound. Frequent feedback and accurate production are also important during this phase of intervention.

As the learner refines the new skill, continued practice helps to establish retention of that skill. Feedback is faded as speech sound accuracy increases. Self-monitoring may also be utilized to maximize external focus on the results of the articulatory movements and resulting acoustic output.

Lastly, the learner advances from skill execution to the integration of the new motor skill, accurate speech sound production. This phase allows the learner to utilize the new skill effortlessly in many phonetic contexts and in many communication contexts.

17. How does feedback change throughout the course of intervention?

Based on the principles of motor learning, feedback type and frequency change throughout the course of intervention. As the child progresses from skill acquisition to skill retention, feedback frequency is reduced. The goal is for the child to begin to rely on their own external focus and self-monitoring to self-assess their own productions for accuracy. Further, as the child progresses from skill acquisition to skill retention, feedback type changes from knowledge of performance to knowledge of results.

18. How are feedback and conditions of practice structured for acquisition?

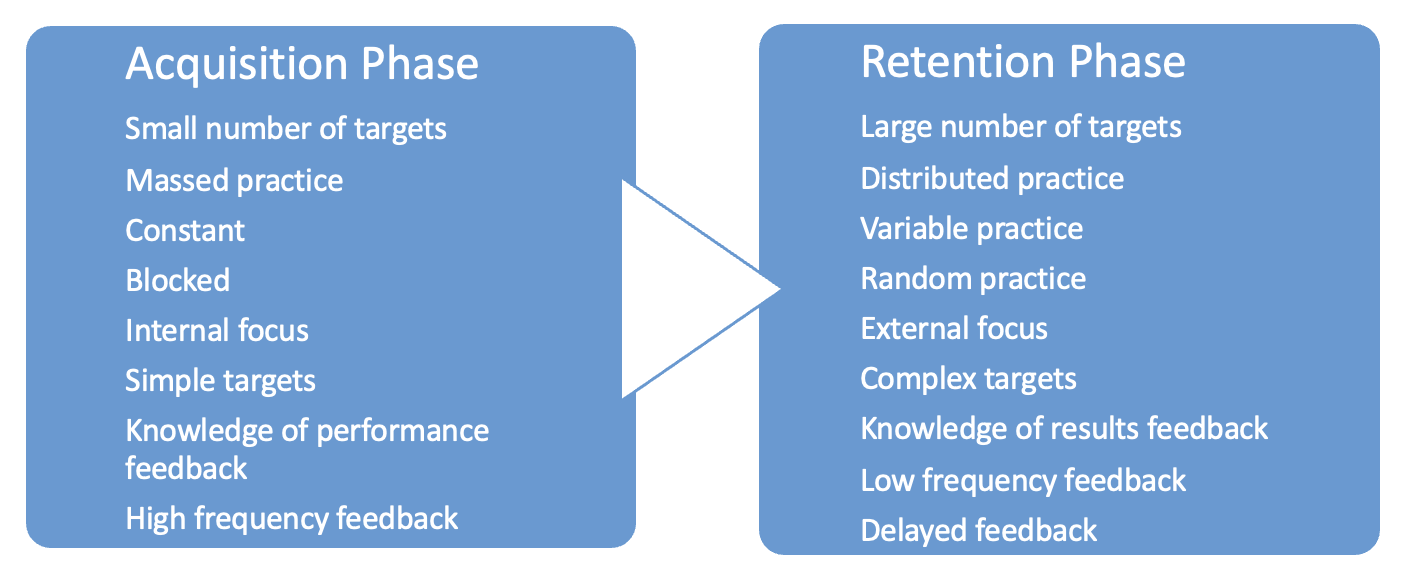

There is some limited evidence to support the efficacy of certain feedback and practice conditions of practice that are more optimal during the skill acquisition phase of intervention. Broadly, the following can be applied during the acquisition phase of speech sound intervention:

- Small number of targets

- Massed practice

- Constant

- Blocked

- Internal focus

- Simple targets

- Knowledge of performance feedback

- High-frequency feedback

- Immediate feedback

19. How are feedback and conditions of practice structured for retention?

There is some limited evidence to support the efficacy of certain feedback and practice conditions of practice that are more optimal during the skill retention phase of intervention. (Bislick et al., 2012). Broadly, the following can be applied during the retention phase of speech sound intervention:

- Large number of targets

- Distributed practice

- Variable practice

- Random practice

- External focus

- Complex targets

- Knowledge of results feedback

- Low-frequency feedback

- Delayed feedback

20. Can you pull this all together for me?

Pre-Practice Conditions | |||

| Motivation to learn |

|

|

Understanding of the task |

|

| |

Stimulability of targets |

|

| |

Practice Conditions | Often associated with skill acquisition | Often associated with skill retention | |

| Practice Amount | Small Small number of targets/trials/sessions | Large High number of targets/trials/sessions |

Practice Distribution | Massed Practice certain number of trials or sessions in short period of time | Distributed Practice certain number of trials or sessions in a longer period of time | |

Practice Variability | Constant Practice same target in same context | Variable Practice different targets in different contexts | |

Practice Schedule | Blocked Different targets practiced in separate successive blocks or treatment phases | Random Different targets are practiced simultaneously, mixed together | |

Attentional Focus | Internal Focus on body movements, placement of articulators | External Focus on the outcome of the movements – the resulting sounds/words, the acoustic signal | |

Target Complexity | Simple Easy, earlier acquired sounds and sound sequences | Complex Difficult, later emerging sounds and sound sequences | |

Feedback Conditions | |||

| Feedback Type | Knowledge of Performance Specific feedback about how a speech sound was produced | Knowledge of Results Feedback about the accuracy of the production, whether correct or incorrect |

Feedback Frequency | High Feedback after every attempt at production | Low Feedback after only some productions | |

Feedback Timing | Immediate Feedback immediately following a production | Delayed Feedback provided with a delay | |

References

Bernthal, J. E., Bankson, N. W., & Flipsen, P. (2017). Articulation and phonological disorders: Speech sound disorders in children. (8th Ed.). Pearson.

Bislick, L. P., Weir, P. C., Spencer, K., Kendall, D., & Yorkston, K. M. (2012). Do principles of motor learning enhance retention and transfer of speech skills? A systematic review. Aphasiology, 26(5), 709-728.

Lowe, M. S., & Buchwald, A. (2017). The impact of feedback frequency on performance in a novel speech motor learning task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60, 1712-1725.

Maas, E., Gildersleeve-Neumann, Jakielski, K. J., & Stoeckel, R. (2014). Motor-based intervention protocols in treatment of childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 1, 197-206.

Maas, E., Robin, D. A., Austermann Hula, S. N., Freedman, S. E., Wulf, G., Ballard, K. J., & Schmidt, R. A. (2008). The principles of motor leaning in treatment of motor speech disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 277-298.

Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D. (2005). Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis (4th Ed.). Human Kinetics.

Wulf, G., & Shea, C. H. (2004). Skill acquisition in sport. Routledge.

Yorkston, K. M., Beukelman, D. R., Strand, E. A., & Hakel, M. (2010). Management of motor speech disorders in children and adults. (3rd Ed.). Pre-Ed.

Citation

Koch, C. (2023). 20Q: Principles of motor learning and intervention for speech sound disorders. SpeechPathology.com. Article 20589. Available at www.speechpathology.com