From the Desk of Ann Kummer

Choosing interventions for language disorders in the adolescent age group is challenging for both pediatric and adult-focused speech-language pathologists. Language issues at this age are often subtle; yet can affect many aspects of communication and learning, including reading, writing, memory, executive function, and problem-solving. Language disorders in adolescents can affect their academic success, and also cause social, emotional, and behavior issues. Despite these concerns, teachers are often not aware of these underlying issues. In addition, they don’t always recognize the role that speech-language pathologists can play in remediating certain language issues that are affecting academic performance.

Providing speech and language services for adolescents has unique challenges and may require the use of different intervention and service delivery approaches than are used with younger students. Therefore, I am delighted that Dr. Judy K. Montgomery, a well-known and highly respected expert in language disorders, has agreed to answer questions about the identification and treatment of adolescent language disorders for this edition of 20Q.

Dr. Montgomery is professor and the Founding Chair of the Communication Sciences and Disorders Department at Chapman University, Irvine, California. She is also the Executive Director of the Scottish Rite Childhood Language Center in Santa Ana, California. Dr. Montgomery is a Board Certified Specialist in Child Language and serves as Editor-in-Chief of Communication Disorders Quarterly. She is an active member of ASHA’s Special Interest Group 1 (Language Learning and Education) and a member of the Council for Clinical Certification (CFCC). She has authored or co-authored over 40 articles and several books, including her most recent book which is as follows: Moore, B.J. & Montgomery, J.K. (2018). Speech Language Pathologists in Public Schools, 3rd ed. Austin, TX: Proed.

Most remarkably, Dr. Montgomery is a former ASHA president and holds Honors of the Association, which is the highest award given by ASHA.

Now...read on, learn and enjoy!

Ann W. Kummer, PhD, CCC-SLP, FASHA

Contributing Editor

20Q: Adolescent Language Intervention: What Works?

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- identify specific language disabilities that significantly impede academic growth in students in middle and high school.

- contrast narrative, expository, discourse tools in language therapy for adolescents.

- create and apply effective interventions for students using evidence-based practices.

1. What are typical adolescent language disabilities?

Specific language impairment (SLI) describes a disorder of language production and/or comprehension without a known cause (hearing impairment, neurological insults, intellectual disability, or autism.) It is a developmental disorder that appears in early childhood and continues into adolescence, manifesting as language and cognitive delays in speaking, reading, writing, memory and problem solving. Other terms may be used in various settings such as language disorders, primary language disorder, language-learning disabilities. By adolescence, these students are typically identified by their highly noticeable reading disabilities. It is obvious that SLI is not very specific!

2. Why do students have these difficulties?

Researchers and clinicians cannot find a reason for these difficulties but they can measure them. Comprehensive assessments typically show language and reading impairments on norm-referenced measures between 1.5 and 1 standard deviation below the mean, characterized by slow expressive language development (SELD). Large numbers of these SELD youngsters achieve in the average range during school age, and do not need further assistance. Spoken language deficits are frequently overlooked by families and teachers because “smaller than typical vocabularies, more than usual grammatical errors, and sparser than expected narratives…are not obvious” (Ukrainetz, 2015, p. 159). SLI tends to be highly persistent, with language delays lasting into adolescence, often accompanied by academic achievement deficits, social incompetence, and behavior problems.

Many studies in the last thirty years have underscored the difficulties expressed by these children who are “on the edge”, developing age-appropriate language skills for a period of time, and then falling behind again when more linguistic skills were needed to read with meaning, increase vocabulary, or organize and analyze. Some returned to more supportive educational environments for part of the day, and others ran the risk of not completing high school or attending alternative settings. Public school districts in the United States do not recognize SLI as a category. They use language delayed or language disordered, or language problems—thus meeting the requirements for the federal eligibility category of speech or language impairment. Specific eligibility requirements are determined by each state (Montgomery & Moore, 2018).

Finally, perhaps the most interesting phenomenon for students identified as SLI has been tracing the slow rate of development for their four key areas: syntax, semantics, discourse, and pragmatics. The prevailing deficit area has been syntax, often called the hallmark of SLI (Ukrainetz, 2015). Thus, increasing numbers of clinicians have focused on developing syntax skills in adolescents, with considerable results. We will follow the same evidence-based practice in this program- vocabulary, syntax, expository text, and discourse. Each of these is a component of academic language.

3. So, what is academic language?

Academic language is a term used to describe the school related language contexts that students encounter in their learning environments. For example, listening to a teacher, writing/presenting a report, group discussions, reading textbooks, asking a question about facts, developing a point of view all use academic language. These interactions only occur at school, however, they are a precursor for the world of work ahead for secondary students. If they have language disabilities they will need to be systematically taught these skills. Examples are: elaborated noun phrases (old rusty bikes); changing verbs to nouns (erupt to eruption; colonies to colonization); verb phrases (had climbed); clausal expansions (carefully washing); relative clauses (that); and others. My favorite is relative clauses!! I teach the concept to my students, and they gradually begin to use it in their writing, and then more quickly into their speaking. They begin to use academic language—and their classroom discourse changes substantially- plus they can absorb and retain more information. We want them to use academic language when asking and answering questions because it “lifts their language” (Dunaway, 2012). I refer to this as “on beyond Brown’s stages”- since we do not have milestones after age 5 years. We will practice with some examples of relative clauses and reconfiguration later in this program.

4. What role does vocabulary size play in academic language?

Vocabulary – the collection of words students use to communicate—is basic to academic language development and acquiring, and remembering, new knowledge. It begins as personal words in the home environment, growing rapidly as the child’s world expands dramatically when he or she goes to school, or joins any group activity with other children on a regular schedule. A typical child has a 2-6 words at 12 months of age; 10 words at 15 months; 200-300 at 2 years; 1,000 at 3 years; 1600 at 4 years; 2200 at 5 years--- and then 6,000 words at age 6. Guess what happened! The environment changed dramatically, and now this child has an enormous expressive vocabulary (www.childdevelopmentinfor.com). The march toward academic vocabulary has begun!

Literate oral language, another term for academic language, is the key to students being, or not being, at grade level standards. “Academic language is a specialized language-both oral and written- that facilitates communication and thinking, and is related to the disciplinary content- what is being learned in the classroom” (Nagy, 2012 p.). Looking at this from the middle or high school level, it is easy to recognize that students will be immersed in the vocabulary of the disciplines that are studying- science, history, mathematics, government, etc. The vocabulary will be new – and noun-heavy, or verbs that quickly become nouns, or adverbs- e.g. its mine, a mine, mining, miners, mined, ore, gold, claims for a state’s early history. Syntax structures come into play. Words that look alike, or sound alike, all have subtle, but different meanings. The SLP will need to select another “chunk” of the academic vocabulary in the textbook, and use it in therapy.

5. I have heard and read about evidence-based practice, but what does it mean for me as a clinician?

An official definition of EPB is “an approach in which current high quality research evidence is integrated with practitioner expertise and client preferences and values into the process of making clinical decisions” (ASHA, 2005). It means that we are committed to reading and using the strategies that have proven most efficacious. As clinicians, we need to keep a running record of how our students are performing, and then be nimble enough to make changes from month to month, maybe session to session. Is the student performing at 80% level or above—time to move on to the next goal. If not, it is time to re-teach, change the approach, retrace our steps, adjust the reinforcement. When we work with adolescents, time is fleeting. If an approach is not successful- change it! Don’t wait. Be clear and honest with clients and students at the high school level. We are all committed to increasing their academic skills- for adolescents; there is no time to waste!

6. How can I measure the development of syntax, vocabulary, expository text and discourse in my clients?

Develop a speech to home communication link, so your students can get home reinforcements for speech/language accomplishments. If this is not possible- make it a speech to classroom communication link with “payoffs” in the classroom. You may not be able to do this for all of your clients- but you should still do it for some of them. This may be their last opportunity to have someone, with your skills and commitment, who cares about their vocabulary, academic language, and ability to communicate at an adult level.

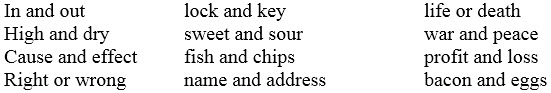

7. Would you give some examples of how to expand vocabulary skills for adolescents?

I find it helps to focus on some vocabulary words that will result in lots of related words in a short period of time. I use the lists of words (these are expository lists not narratives) from the Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists (Fry & Kress, 2011). These are lists of non-reversible word pairs. These words always appear in the same order- thus your students learn two words at the same time- very efficient! - plus the relationship between them! You read the first word, and the student(s) completes the word pair by saying the final word aloud. Do it aloud for the first several times, then ask the student to write the paired word on a small chalkboard or wipe-off slate.

(There are 61 word pairs)

In a small group, ask students to quiz each other. You will be amazed how quickly they learn these. There is an element of automaticity that sets in, and they are quite pleased with themselves. Only introduce 5 words at a time, not the whole list. Go to the next group of words once they become proficient as the responder, and then the initiator.

8. How would an IEP goal be written?

An IEP goal for a student working on the previous adolescent vocabulary goal follows:

By March 2018, Dewayne will analyze the meaning of words and phrases in their context by reading and writing 10 non-reversible word pairs with 80% accuracy without assistance 4 of 5 times.

9. I enjoy, and am fairly skillful at, reinforcing narrative skills in young children. They love stories! Should I continue to provide narrative language therapy for my adolescent clients?

Actually, no. Narratives are intrinsically more interesting and exciting for students- in fact, for all of us. With a few exceptions, most people would prefer a story to a series of facts. However, the pursuit of academic language is so important for adolescents that they must be re-directed toward expository language. It is the language of their future. Use their textbooks whenever you can. Ask them to bring their history or science or whatever book to speech. Or you can arrange to get a copy of their current textbook; or make copies of a few pages that have already been covered. Select a page in a chapter they have already studied. Read a sentence aloud. Ask the student to re-state it in his/her own words. Write what the student says. Read it back to him. Ask if he wants to add more to it, or change any of it. It should be a fairly close approximation of what the sentence was about. Next, you will talk about something on the same page, but not read it exactly. Ask the student to find the sentence about that topic. The purpose here is to grasp what the sentence is about, but not word for word. You want to have a conversation from the book to the student; then from the student to the textbook. This is a precursor to academic language, so students learn to use their own words and not copy sentences without comprehension. Do these exercises at the beginning and end of the therapy session. No more than 3 pairs each time. You should be able to work up to 20+ pairs in a short time- that’s 40 new and meaningful vocabulary words in a flash!

10. Please compare Narrative and Expository text.

A comparison is a good idea, since these language forms have very different purposes. Narrative text provides a story with characters, specific locations, and action episodes. The reader is drawn into the story. Young children learn most of their information from stories, characters and action that may not be truthful, but are always eventful. That is, full of events! In narratives, things happen to people, animals and characters, and the events can be retold in the same ways, or in new ways with twists and turns, personalities, surprises, and reactions! Who can forget Dr. Seuss stories with Thing 1 and Thing 2? Narratives are of central importance until fourth grade when facts take over the limelight.

Exposition, as a contrast, is grounded in facts. Anyone could discover and share these facts. The facts don’t change. Expository texts describe, inform, explain, and present factual information from a reliable source. The author is less important – any well-informed person could convey these facts. Adolescents discover that the vocabulary is more precise and less familiar, the syntax more complex, and the organization more varied. While there may be characters in the story- George Washington for example- the purpose of the text is the formation of a new nation.

Needless to say, reading below the 4th grade level looms as an enormous obstacle for our students with language/literacy challenges when they encounter expository text. This is when we take our therapy skills up a notch or two!

11. How are expository text sessions organized and delivered by speech-language pathologists?

Fortunately, expository text seems to come along at just the right time in our education curriculum. By mid-fourth grade, students read independently, grasp new concepts with ease, greatly expand their vocabularies, try out some leadership skills, and build more secure social relationships so they can take chances and have opinions. Building expository discourse skills is the next logical step for the typical learner, and therefore must also become the purpose of the SLP providing language intervention for adolescents. Their language must keep up with their peers. It is not easy. SLPs will notice that texts become lexically dense. Vocabulary words are lexically dense, carrying a large amount of information. Students need to learn signal words (conjunctions and connectives), phrase structures (compare/contrast, most prepositions) and organizational words (at first, secondly, combination, almost, in conclusion) as grammatical functions. Keep in mind that few of us ever learned these critical language tools from an English Grammar Book. We learned them by interacting with the expository content- the excitement of learning those facts! We need to provide this same environment in our therapy setting, and link it to their classroom experiences. A key tool is using text structures.

12. I am not familiar with expository text structures. How does it work?

I have found the 7 text structures of expository text to be one of the most useful therapy tools. If the text is a narrative - it is a story. If it is an expository text – it is a fact. If it is a biography – it is a combination of a life story and the facts and knowledge critical to that key person. Students read all three types of books - however, SLPs will need to provide the most scaffolding for expository test. The seven text structures are:

- Description

- Lists

- Sequences of activity

- Cause and effect

- Problems with solutions

- Persuading others to see the use or importance of a fact

- Compare (what is the same) and contrast (what is different) about the facts

Adolescents need to be shown how to engage with these discourse structures. They are all language-rich and must be practiced many times over. If the curriculum topic is volcanoes- then the SLP will introduce wipe-off boards for students to write or draw the facts connected with each of the structures. This is how it flows.

- Description- draw or write words related to how a volcano appears/looks

- Lists- list where volcanoes can be found in the world; list the main parts of an active volcano; list the dangers of living near a volcano; list what precautions people take in Hawaii or Italy.

- Sequences- how do scientists know when a volcano is about to erupt?

- Cause and effect- what causes rich soil for planting? How do many smaller eruptions reduce the danger?

- Problems with solutions- Name one problem and a solution related to volcanoes. Are these explosive events ever helpful to humans?

- Persuading others- Using facts from the textbook, try to convince others to become seismic scientists of the future; why would this be important?

- Compare and contrast- Name 2 famous volcanoes and their location on earth. Describe how they are alike and how they are different

Sometimes students carry their ideas back into the classroom to organize their work. Or teachers will ask SLPs to demonstrate the 7 text structures. The purpose is to organize students’ thinking and writing on a “chunk of the curriculum”. Teachers are often amazed at the high caliber of discussion many students can display after this degree of scaffolding. I think you’ll love it!

13. I am still not sure I know what discourse is.

Discourse is a unit of language longer than a sentence. We use discourse to describe, inform and explain. Discourse has specific linguistic characteristics, including strong links to oral language. Heavily influenced by syntax, it is the primary method that students gain new facts and information beyond third grade. It is beneficial to read new fact-based information, but it requires a considerable amount of guided oral language for it to “stick”.

14. What are some of the steps in developing informational discourse in adolescents?

Students who can use vocabulary that is appropriate, precise, and meaningful to others will be able to take part in class discussions or small group interactions in the therapy room. Claudia Dunaway proposes tips on “lifting your language”- and using power vocabulary. This takes time to develop, but once mastered will be of value throughout school, first jobs, and reaching personal and professional goals. It is another way to look at how and why we learn to expand our vocabulary in school. Discourse is one of the many places students will use this language skill. An SLP, Dunaway (2012) has worked with adolescents for many years, and has shared her techniques in books and articles found in the reference section. She does not tell students to use “grown-up” words, or 10th grade vocabulary. Instead, she offers to give them POWER WORDS

- Practice saying multi-syllabic words in therapy, then at home, then with friends. Plan on adding several new words that you have heard others use: obviously, participate, combination, establishment, conscientious, gracious -Might be some of those. Practice with the words you might use with them—discuss the times or places you could use these words.

- The SLP reads 3 sentences aloud from a textbook (expository text). Summarize the idea in one sentence. (This is difficult, but the students get very good after awhile!!)

- Instruct students to listen to famous speakers on You-Tube. Repeat their words. Repeat their sentences. Make your voice sound like them. Use their words. Those words belong to you, too.

- Avoid using the following words: thing, here, this, is, do, have, bad, happy

- Replace them with these words:

Thing, stuff - object, article, device, gadget, specific name of item

Do, make - perform, accomplish, complete, achieve, cause

Happy - content, satisfied, pleased, joyful, fortunate, cheerful, delighted (Dunaway, 2012, p.86)

These are great techniques to practice in therapy, in conversation, with small groups, in supportive classrooms.

15. How is this approach related to reading and literacy?

After a point, everything is related to reading and literacy! “Reading, language arts and communication skills are linked and interdependent in the educational process” (Moore & Montgomery, 2018, p. 234).

Speech-language pathologists play a critical and direct role in the development of literacy for children and adolescents with communication disorders…Speech-language pathologists also make a contribution to the literacy efforts of a school district or community on behalf of other children and adolescents. (ASHA, 2000b).

16. What are the decontextualized demands that clinicians talk about?

Informational discourse is typically decontextualized. The student needs to recognize and speak about events that occurred at a different time and space, or are abstract. Students may not have encountered these questions before. Higher order thinking skills are necessary to make logical inferences. Contextualized information is found in places we frequent often, our homes, classrooms, sports fields, clubhouse- whatever we know well. Sentences do not need to be precise. Everyone is familiar with the articles around the area. Everyone knows the context. It is shared knowledge. Here is a comparison sample.

Contextualized Example: At home (much context), your older brother asks you “where is your lunch?” (The shared knowledge is the direct experiences of your family)

Decontextualized Example: In the 7th grade classroom (no context) your teacher asks you “Where is Australia?” (Teacher knows, and it’s in your textbook, but you don’t know how to talk about it).

Some educators and linguists refer to learning itself, as simply contextualizing the world around us!

17. We have to keep data on student progress in the schools- what should I measure?

You should measure student progress in the four major areas of expository text: syntax, semantics, discourse, and pragmatics. These are the goal posts of adolescent language development, increased reading comprehension, and life skills.

18. The state standards are critical signposts of learning in my high school. How can I write goals that integrate the standards when the students in my caseload have limited language and vocabulary skills?

Goal writing for adolescents is a process of combining a long-term goal from the curriculum standards with a life skill. Both are necessary. Here are some examples. Note that they do not have specific dates, but rather over a time period to be checked at least annually. Try writing comprehensive student goals for expository discourse. The goals will have greater flexibility, cover several types of student skills in one goal, occur in several academic environments and use a less specific date.

Given verbal and/or written prompts, Carlos will maintain a conversational topic for a minimum of 7 turns with an adult or peer in 4 out of 5 opportunities (80%) over three consecutive sessions with mild, decreasing to, no cues.

By the end of the third grading period following the Annual Review, Andrew will use grade level vocabulary to define and correctly use new words in compound and complex sentences, using core curriculum vocabulary, expository discourse vocabulary words, and selected word lists, for 15 out of 20 target vocabulary words.

19. Are speech-language pathologists critical supports for language-impaired adolescents to become fluent in academic language?

Absolutely!

20. I want to work with a teacher partner in the science class at my high school. I am friendly with the teacher and I admire how she teaches. Several of my speech/language students are in her class. How do I get prepared? How do I get in her class to co-teach?

It is not easy to enter the classroom. It appears that you have an excellent opportunity with a teacher friend, plus some of your speech students are in her class. Here are some helpful hints from those of us who have been there:

- You may have to invite yourself in “to watch and learn” for several weeks. Listen to the students’ language

- You should listen to more than one teacher led discussion- try not to take notes, give full attention and absorb what is going on.

- Decide what role the teacher plays in this room- leader, facilitator, guide, evaluator, encourager?

- Decide where you could model your expository discourse with the teacher – from the front of the room? In separate sections in the room? In a Q&A format?

- Are some students using academic language? Can they handle decontextualized content? Are they discussing facts, ideas and opinions?

- Bring in prepared questions, with potential answers in written form. Try to stick to your plan.

- Be sure the students have first name tags on their desks or shirts- or a seating chart- you need to know some student names so you can call on them.

- Front load your speech students so you can call on them in class

- Limit the first few sessions to 5 minutes. Set a timer. Stop on time, no matter how good it is going!

- De-brief with the teacher later that day, or as soon as possible. Be honest with each other. What worked? Why? Let’s check and see what they learned!

Good luck, and enjoy the ride with adolescents as they seek to grasp these adult language tools.