Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Audiology Essentials for Non-Audiologists, presented in partnership with RIT/National Technical Institute for the Deaf, presented by Carly Alicea, AuD, PhD, CCC-A.

It is recommended that you download the course handout to supplement this text format.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the role, responsibilities, and scope of practice of audiologists and how their work intersects with that of speech-language pathologists (SLPs).

- Explain key audiological concepts relevant to SLP practice, including hearing loss and amplification.

- List at least three indications that a client should be referred for an audiological assessment.

Introduction/About NTID

I am pleased to be here today to talk about audiology essentials for non-audiologists. Before we dive into the main topic, I would like to share a little about NTID and who we are. NTID stands for the National Technical Institute for the Deaf. It is one of the nine colleges of the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, New York. NTID was established in 1965 through an act of the U.S. Congress to provide higher education opportunities for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Since then, we have been committed to creating an inclusive learning environment that combines technical and professional training with strong communication access and support services.

About NTID Students

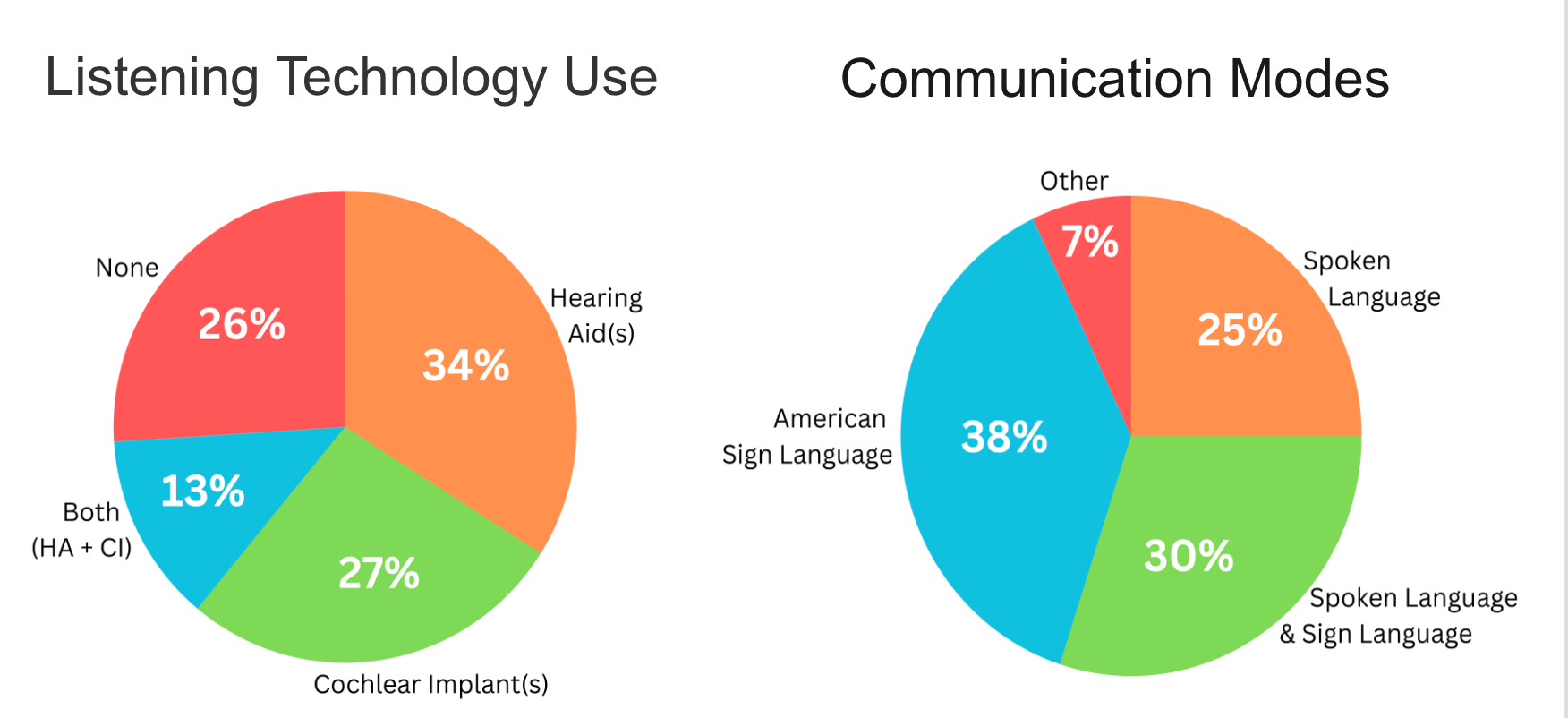

At NTID, we serve a diverse array of students, and Figure 1 provides some information about our students.

Figure 1. NTID student statistics. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

You can see how diverse our student body is, not only in terms of communication modes but also in listening technology use. Twenty-five percent of our students use spoken language to communicate, while 38% use American Sign Language. Thirty percent use a combination of spoken language and sign language, and 7% use other communication modes.

When we look at listening technology, we see similar diversity. Thirty-four percent of our students use hearing aids, including bone-anchored hearing aids. Twenty-seven percent use cochlear implants, and 13% use a cochlear implant on one side and a hearing aid on the other. Twenty-six percent of our students do not use any listening technology at all.

About NTID Au.D.s & SLPs

At NTID, we have ASHA-certified audiologists and speech-language pathologists who provide on-campus audiological and speech-language services to RIT and NTID community members. Our primary goal as a department is to serve the community and support the diverse communication needs and communication skill development of our deaf and hard-of-hearing college students. Our audiologists and speech-language pathologists are fluent in American Sign Language, and we prioritize matching the communication preferences of each student we work with.

Our Services

Here you can see an example of some of the services we provide. We operate full-service audiology and speech-language pathology clinics on campus, and we are very excited to be here today partnering with speechpathology.com to bring you this course. If you are interested in learning more about NTID, brochures are available as handouts for this course so you can explore more about who we are.

Today, I will share as much as I can about what speech-language pathologists and other professionals should know about audiologists and our work.

Importance of Interdisciplinary Collaboration

To set the stage for today’s discussion, I want to highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between audiologists and speech-language pathologists. Understanding each other’s professions and working together can significantly improve client outcomes.

First, accurate diagnosis is essential. Hearing loss can directly affect speech and language development in children. If hearing loss is undiagnosed or unidentified, it can complicate the diagnosis of other speech-language disorders, such as aphasia, and untreated hearing loss can negatively affect progress in speech-language therapy. Collaboration ensures that speech-language pathologists have the information they need to feel confident in their diagnoses and to work effectively with their clients.

Second, coordinated intervention plans are critical—particularly for individuals with hearing loss who may require both aural rehabilitation and speech-language therapy. Collaboration helps align therapy approaches with each client’s hearing abilities and needs.

Third, interdisciplinary collaboration maximizes communication outcomes. Clients benefit from a team-based approach that holistically addresses hearing and speech-language needs.

We also see valuable collaboration opportunities in cases of auditory processing disorders. Audiologists play a key role in diagnosing these disorders, while speech-language pathologists support language processing skills, phonological awareness, and listening strategies—making this another crucial area for joint efforts.

Finally, both professions share responsibility for client and family education. When audiologists and speech-language pathologists communicate unified, consistent messages to clients and caregivers, this reduces misinformation, promotes clarity, and supports better overall outcomes. In turn, this teamwork improves the quality of life for the individuals we serve.

How Much Do You Already Know About Audiology?

I want to start with a pop quiz to test your knowledge.

1) Conductive hearing loss results from a problem in which part of the ear?

- Outer

- Middle

- Inner

- A and/or B

2) An audiologist’s scope of practice includes which of the following?

- Diagnosis of hearing disorders

- Vestibular rehabilitation

- Teaching speechreading

- All of the above

3) A person must have hearing levels in the profound range to be a candidate for a cochlear implant.

- True

- False

4) Which of the following is a “red flag” that suggests referral to an audiologist is needed?

- Echolalia

- Mumbling or whispering

- Struggles with phonological awareness

- Part-word repetitions

By the end of this presentation, you should be able to answer all of these questions confidently if you cannot already. Take a moment now to review the questions. If you aren’t sure about your answers, keep them in mind as we move through today’s presentation. Watch for the points where the answers will come up so you can check your understanding.

What Do Audiologists Do All Day?

Let's dive into what audiologists do and what a typical day might look like for an audiologist.

Audiologist Roles, Responsibilities, and Scope of Practice

We will begin by examining an audiologist’s role, responsibilities, and scope of practice. While capturing everything is challenging, here are some key highlights.

Audiologists diagnose hearing and balance disorders and related conditions such as auditory processing disorder. They also provide treatment for hearing, balance, and related disorders. A significant part of their work includes hearing screenings, ranging from newborn hearing screenings to large-scale program oversight. This can involve not only performing screenings but also establishing protocols, managing programs, tracking data, and supervising staff.

Audiologists may provide aural rehabilitation or habilitation services, including teaching speechreading, developing auditory skills, and training clients in communication strategies. They also offer psychosocial and adjustment counseling related to hearing loss—not only for clients, but also for parents, caregivers, family members, and other communication partners.

Public education is another important responsibility, with audiologists promoting the prevention of hearing loss, tinnitus, and falls. They may also design, implement, and supervise hearing conservation programs. Finally, audiologists can work in various settings, reflecting the diverse scope of their profession.

Common Work Settings and Patient Populations

You will find audiologists working in a wide range of settings. They may be in hospitals, medical centers, private audiology clinics, or hearing aid centers. Educational audiologists can be found in schools, ranging from preschools and mainstream K–12 settings to schools for the deaf. Many work in universities or research institutions. Others serve in VA centers, VA hospitals, and other military settings. Audiologists may also be in rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, public health departments, or community outreach centers.

Audiologists serve clients across the lifespan—from pediatric audiologists who work with newborns to those specializing in care for the oldest members of our communities. In all these settings, there is significant overlap in roles, responsibilities, and scope of practice between audiology and speech-language pathology.

Areas of Overlap Between SLPs and Audiologists

Here are a few examples of areas where audiology and speech-language pathology overlap. Both professions may conduct hearing screenings. Evaluation and management of auditory processing disorder is another shared area where collaboration is especially valuable. Aural rehabilitation also falls within the scope of both audiologists and speech-language pathologists. In addition, both provide counseling and education for clients, their family members, friends, and caregivers.

Understanding Hearing and Hearing Loss

Let’s now turn our attention to hearing and hearing loss. To understand the different types and degrees of hearing loss, we first need to know how hearing works.

How Humans Hear

Let’s revisit your undergraduate or graduate school days and how humans hear. One of the most critical basics is that sound is vibration, which is central to hearing. Sound travels through the air as vibrations, and hearing begins when those sound waves are funneled into the outer ear, or pinna.

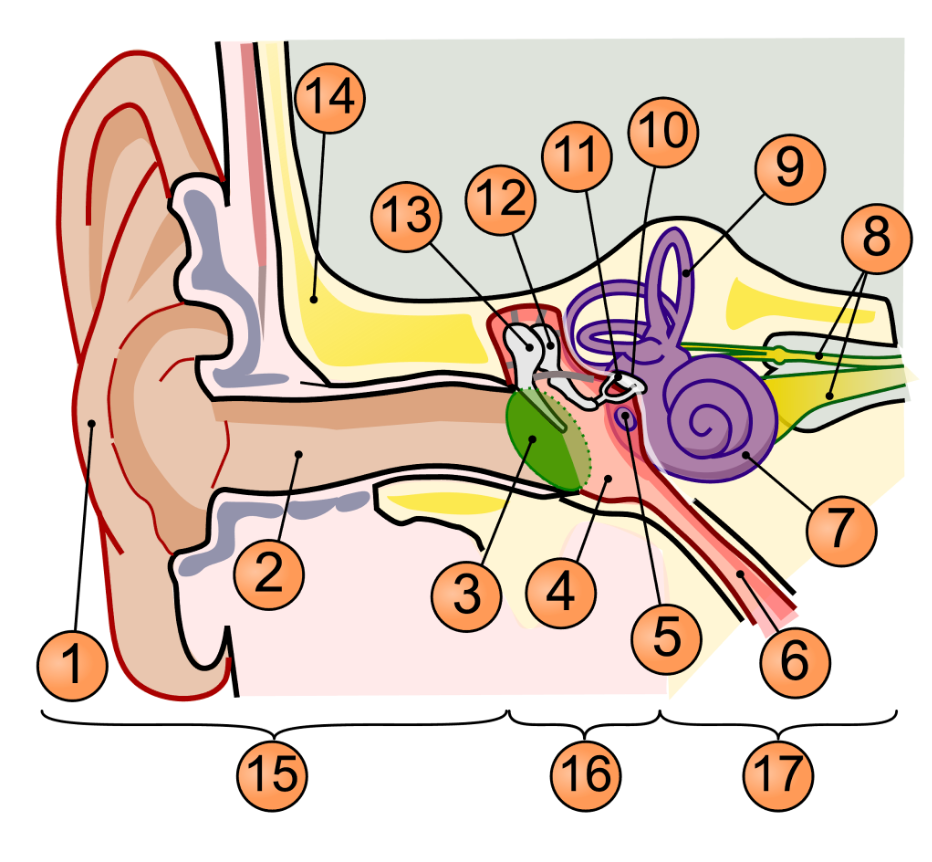

Here is an illustration of the ear in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Illustration of the ear. (Click here to enlarge the area.)

In this illustration, hearing begins at number one, the outer ear. Sound waves are funneled into the pinna and travel down the ear canal, number two, toward the eardrum, or tympanic membrane, as number three. When sound waves strike the eardrum, they cause it to vibrate.

These vibrations are passed along to three tiny bones in the middle ear—the ossicles—numbered 11, 12, and 13 in the illustration. The ossicles consist of the malleus, incus, and stapes, and their role is to continue transmitting the sound vibrations through the middle ear while amplifying them. The smallest bone, the stapes (number 11), presses against the entrance to the cochlea in the inner ear.

The cochlea is a fluid-filled, snail-shaped hearing organ. When the stapes moves against its membranous entrance, the fluid inside the cochlea moves. This fluid movement sets the hair cells lining the cochlea into motion. As these hair cells move, they trigger a chain of chemical reactions that convert the fluid vibrations into electrical signals.

These electrical signals are then carried by the auditory nerve, shown as number eight, to the brain, where the sound is interpreted. Any disruption in this chain—from the outer ear to the brain—can result in hearing loss.

Types of Hearing Loss

There are different types of hearing loss, and they are differentiated based on the part of the auditory system that is not functioning as we would expect.

Conductive

One type of hearing loss is conductive hearing loss, which occurs when there is a problem or dysfunction in the outer and/or middle ear. Examples include complete ear canal blockage from earwax, middle ear infections where fluid builds up and becomes infected, and otosclerosis. In this condition, the ossicles harden or stiffen, preventing them from transmitting sound effectively through the middle ear.

These issues involve the outer and/or middle ear, resulting in conductive hearing loss. This type of hearing loss can be either temporary or permanent. For example, hearing loss from an ear infection is typically temporary, resolving once the infection is treated. Other cases are permanent, meaning they cannot be corrected medically. In some situations, a surgical or medical intervention might be possible, but if the individual chooses not to pursue it—or if it is ineffective—the conductive hearing loss remains permanent.

Sensorineural

Sensorineural hearing loss is another type of hearing loss that occurs when there is a problem in the inner ear and/or the auditory nerve that carries sound signals to the brain. Unlike conductive hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss is always permanent—at present, there is no way to restore the damaged hearing to normal levels.

Common causes include aging, where the hair cells in the cochlea become damaged over time; noise exposure, which can similarly damage these hair cells; and certain viral infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), which is a frequent viral cause of sensorineural hearing loss. In all these cases, the issue lies in the inner ear or the auditory nerve, which is why the hearing loss is classified as sensorineural.

Mixed

The last type of hearing loss is mixed hearing loss, which occurs when both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss are present at the same time.

One typical example is a child with sensorineural hearing loss due to a genetic condition. If that child then develops a significant ear infection, the infection can cause an additional conductive hearing loss. In that moment, the child is simultaneously experiencing both types of hearing loss—sensorineural from the genetic condition and conductive from the ear infection—making it a mixed hearing loss.

Degrees of Hearing Loss

Another vital way to describe hearing loss—beyond its type—is by its degree, which refers to how much hearing loss someone has, or conversely, how much they can hear. Audiologists measure hearing levels in decibel hearing level (dB HL) and describe them using specific ranges.

For adults, typical hearing sensitivity is between –10 and 25 dB. For children, the range is slightly narrower—about –10 dB to 15 dB—because children generally have more acute hearing and are still developing language skills. Even a slight hearing loss (16–25 dB) can have a greater impact on speech and language development than it might for an adult.

Mild hearing loss is thresholds between 26 and 40 dB HL, moderate hearing loss between 41 and 55 dB HL, and moderately severe hearing loss between 56 and 70 dB HL. Severe hearing loss typically falls between 70 and about 80–90 dB HL, and profound hearing loss is at or above 90 dB HL.

When we talk about “hearing levels,” we are referring to hearing thresholds—the softest sounds a person can detect. If the softest sound a person can hear falls, for example, between 26 and 40 dB HL, we would classify their hearing as mild.

It is also common for a person’s thresholds to span more than one category. An audiology report might list a “mild to moderate” hearing loss, meaning some thresholds are in the mild range while others are in the moderate range. This variation is highly individual, and understanding the degree labels is often most useful when discussing their functional impact.

Mild Hearing Loss (26-40 dB HL)

Mild hearing loss refers to thresholds between 26 and 40 dB HL. People with mild hearing loss can hear most conversational speech, but challenges arise if the speaker turns away, speaks softly, or is at a distance. They often have difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments such as restaurants, parties, classrooms, cafeterias, or gyms.

A common characteristic is difficulty detecting soft consonants, which can make speech sound muffled. Many people with mild hearing loss report that they can hear others talking, but it sounds unclear, as if people are mumbling. This is often due to missing those softer speech sounds.

Because individuals with mild hearing loss function well in many listening situations, it can be easily overlooked—especially in adults, who may not realize they have it. Being aware of this possibility is important for speech-language pathologists, as subtle impacts may emerge during evaluations or therapy sessions even when the hearing loss has gone undetected.

Moderate Hearing Loss (41-55 dB HL)

Moderate hearing loss refers to thresholds between 41 and 55 dB HL. People with moderate hearing loss usually hear louder voices and speech occurring close by, such as when someone is sitting right next to them. However, they often miss portions of the auditory signal and rely more heavily on visual and contextual cues.

This may include watching facial expressions, engaging in speechreading—whether consciously or not—and using context and background knowledge to fill in gaps in what they hear. These individuals may not receive the full auditory picture even with louder or closer speech.

In noisy environments or group settings—especially where multiple people are talking at once or conversations overlap—following dialogue becomes significantly more challenging for someone with moderate hearing loss.

Moderately-Severe Hearing Loss (56-70 dB HL)

Moderately severe hearing loss refers to thresholds between 56 and 70 dB HL. For individuals in this range, speech must be loud to be heard, and many everyday environmental sounds—such as a phone ringing, a doorbell, or a knock at the door—may go undetected.

When listening to speech, even if it is loud, they may only catch fragments of words or bits of what is being said. Because so much auditory information is missed, understanding spoken communication can be difficult, even under favorable listening conditions.

Severe Hearing Loss (71-89 dB HL)

People with severe hearing loss have hearing thresholds between 71 and 89 dB HL. They can only detect loud sounds, such as shouting, screaming, sirens, or fire alarms. Most speech sounds are inaudible unless produced at volumes much louder than normal conversation.

If they use spoken communication, it will be heavily dependent on amplification—through hearing aids or cochlear implants—and on visual cues. Without these supports, carrying on a spoken conversation is generally not possible.

Profound hearing loss is the next degree beyond severe, involving even greater limitations in hearing ability.

Profound Hearing Loss (90+ dB HL)

Profound hearing loss occurs when hearing thresholds are greater than 90 dB HL. Individuals with profound hearing loss may perceive very loud sounds only as vibrations, without actually hearing them. Speech is completely inaudible unless they are using very powerful amplification, such as a power hearing aid or a cochlear implant. Even then, environmental sounds are often not detectable.

Reliance on visual and contextual cues remains high for those who use spoken communication. They typically need to see the talker’s face for speechreading and benefit from knowing the topic of conversation to follow along. Even with amplification, they may not receive enough auditory information to understand speech through listening alone.

Now, let’s examine how hearing loss impacts communication and learning, beginning with its effects on children.

How Hearing Loss Affects Communication and Learning

Children

More than 90% of deaf and hard-of-hearing children are born to hearing parents who do not know a signed language. This means most of these children are born into families that use spoken language exclusively, and where no one can provide them with immediate access to a visual language.

Because of this, early assessment and identification of hearing loss are critical. Identifying hearing status as soon as possible allows children to gain earlier exposure to language, access early intervention services, and—if families choose amplification—begin using hearing aids or cochlear implants at a younger age. The primary goal is to reduce the risk of language deprivation.

Language deprivation occurs when deaf and hard-of-hearing children cannot access a complete, consistent language during the critical language learning period. Even children who use amplification may not have full access to spoken language. If they are also not given full access to a signed language, they may be deprived of a complete language. Ensuring that children consistently receive accessible language—spoken or signed—is essential for their development.

Without full language access, children may face:

Language and speech delays include limited vocabulary, grammatical deficits, and impaired phonemic or phonological awareness.

Cognitive delays, since language is foundational to concept development and critical thinking.

Academic challenges include difficulty with reading comprehension, writing, and keeping pace academically, particularly in mainstream settings without proper accommodations.

Social and emotional difficulties include trouble engaging in conversation, building friendships, interpreting social cues, or catching nuanced communication. This can lead to social isolation, frustration, and behavioral issues from communication barriers.

Executive functioning deficits include planning, organization, memory, impulse control, following multi-step directions, and problem-solving.

These impacts can have long-term and even lifelong effects, extending into adulthood. Individuals may encounter barriers to higher education, employment, and full social participation without strong language skills.

Adults

When hearing loss begins in adulthood—after a person has grown up with typical hearing—it can have wide-ranging effects on communication and learning. Adults in this situation may experience:

Difficulty understanding speech, especially in background noise.

Frequent misunderstandings and the need to ask others to repeat themselves, often saying “What?” during conversations.

Challenges with phone conversations or following discussions in virtual meetings.

Increased risk of social isolation due to communication barriers.

Greater risk of cognitive decline, as untreated hearing loss has been linked to changes in brain function over time.

Heightened stress and frustration stem from the effort required to communicate effectively.

Impacts on job performance and career advancement, particularly in roles that require frequent verbal communication.

Strain on interpersonal relationships with spouses, family members, friends, and children.

Therefore, unidentified or untreated hearing loss in adulthood can have broad and significant consequences, affecting both professional and personal aspects of life.

Hearing Technology

Next, I want to discuss different technologies that audiologists may recommend for children or adults with hearing loss.

Hearing Aids

Hearing aids can be used for any hearing loss—sensorineural, conductive, or mixed. However, for individuals with severe to profound hearing loss, hearing aids may not provide enough access to sound for speech understanding through listening alone. While these individuals may still benefit from using hearing aids, the devices often need to be combined with other strategies or technologies to optimize communication.

Modern hearing aids are digitally programmed using a computer, with settings tailored to the individual’s specific hearing thresholds. They come in various styles, including behind-the-ear (BTE), in-the-ear (ITE), and receiver-in-the-ear (RITE). An audiologist recommends the most suitable style based on factors such as:

Degree of hearing loss

Dexterity considerations (e.g., ease of handling batteries or controls)

Personal preferences regarding comfort, appearance, or features

It’s important to understand that hearing aids do not restore hearing to normal. Unlike glasses, which can fully correct many vision problems, hearing aids work by making sounds louder and enhancing clarity, but they cannot replicate natural hearing.

Bone Conduction Hearing Aids/Implants

Another hearing technology that an audiologist may recommend is a bone conduction hearing aid or implant. These devices are typically used for conductive or mixed hearing loss or for single-sided deafness, where one ear has typical hearing and the other has a very significant, often profound, hearing loss.

Bone conduction hearing aids transmit sound through vibrations in the skull's bones rather than through air conduction. A microphone on the device picks up surrounding sounds, converts them into vibrations, and sends them directly to the inner ear through the skull bones.

There are two primary forms:

Headband-worn devices are often used for young children (typically under age five) or for individuals—children or adults—who cannot or do not wish to undergo surgery.

Surgically implanted devices – Available in several types, offering a more permanent solution for candidates for surgery.

Cochlear Implants

Cochlear implants are appropriate for individuals with sensorineural hearing loss in the moderately severe to profound range and for those with single-sided deafness. They are typically recommended when hearing aids are not providing sufficient benefit.

Cochlear implants bypass the damaged cochlea and convert sound into an electrical signal. An external processor contains a microphone that picks up environmental sounds. The processor converts these sounds into electrical signals sent via a transmitter to a surgically implanted receiver. Electrodes within the implant stimulate the auditory nerve directly, taking over the role of the cochlea. The brain then interprets this electrical stimulation as sound.

Assistive Listening Devices

Audiologists may also recommend assistive listening devices to support communication in specific situations. These can include:

Bluetooth-enabled hearing devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants

Remote microphone technology

DM or FM systems for improving speech clarity over distance or in noisy environments

TV listening systems

Captioning devices

Alerting devices for sounds like doorbells, alarms, or timers

In addition to recommending these technologies, audiologists often assist clients with fitting, setup, and training so they can use these devices effectively in their daily lives.

Various Uses of Hearing Devices

It’s important to remember that hearing devices—such as hearing aids or cochlear implants—are not used solely for hearing and understanding speech. While speech perception is often the most recognized reason for their use, many people who are deaf or hard of hearing choose these devices for additional purposes, such as:

Monitoring their speech to help with clarity and self-correction

Increasing environmental awareness by providing access to the surrounding sounds

Enjoying music and enhancing music appreciation

In other words, speech understanding is just one of several meaningful reasons someone might use a hearing device.

When Should I Refer to Audiology?

We’ll look at when to refer a client to audiology. As a speech-language pathologist, specific observations should prompt you to recommend an audiological assessment. Red flags include:

Frequent requests for repetition

Inconsistent responses to sounds or speech

Difficulty with phonological awareness that may be influenced by hearing status

Delayed speech and language milestones in children

History of frequent ear infections, which may affect hearing

Difficulty hearing in noisy environments

The key point is to rule out hearing loss before diagnosing any speech or language disorder. This applies to both children and adults. Knowing a client’s hearing levels ensures that hearing loss is not an unrecognized factor influencing communication before you proceed with a diagnosis.

How Much Do You Know Now About Audiology?

All right, we are back to our pop quiz.

1)Conductive hearing loss results from a problem in which part of the ear?

- Outer

- Middle

- Inner

- A and/or B

2)An audiologist’s scope of practice includes which of the following?

- Diagnosis of hearing disorders

- Vestibular rehabilitation

- Teaching speechreading

- All of the above

3)A person must have hearing levels in the profound range to be a candidate for a cochlear implant.

- True

- False

4)Which of the following is a “red flag” that suggests referral to an audiologist is needed?

- Echolalia

- Mumbling or whispering

- Struggles with phonological awareness

- Part-word repetitions

If there were any questions the first time I showed you this that you did not know the answer to, I hope you know the answer now. So go ahead and look this back over again. I will give you just about 10 or 15 seconds to do so.

Summary

Hopefully, you are now feeling like an expert in audiology and can answer all of these questions. We have reached the end of today's presentation, and I am happy to answer any questions that you may have about any of the topics that I have talked about today.

Questions and Answers

Besides a patient declining medical intervention, what are some examples of conductive hearing loss that can’t be reversed?

Sometimes, a patient may choose medical treatment or surgical intervention, but the procedure may not fully restore hearing to typical levels. The result might be improved thresholds without returning to normal hearing, leaving some degree of permanent conductive hearing loss.

Is there an upper age limit for when a cochlear implant is recommended?

No, there is no strict upper age limit. Candidates have successfully received cochlear implants into their 80s and 90s. The primary consideration is how long the person has been without auditory stimulation. Expectations may differ for older adults who have never used hearing devices or have gone many years without them.

Any suggestions for when a client has tinnitus?

Always recommend a complete audiological evaluation for any client reporting tinnitus. This assessment can help identify potential causes, including hearing loss or other auditory system issues. An audiologist can also suggest strategies or techniques to reduce tinnitus awareness, especially if it interferes with daily life.

Do you have any advice for working with patients with dementia who also have hearing loss?

First, ensure the person has had a recent hearing evaluation to determine what auditory input they can and cannot access. Differentiate, as much as possible, between difficulties caused by hearing loss and those caused by dementia. If the person uses hearing devices, ensure they are in place and functioning before sessions—this includes checking the batteries and using a listening scope to confirm the aids are working. Avoid relying solely on the patient’s report of device function, as this may not be reliable.

References

Please refer to the handout.

Citation

Alicea, C. (2025). Audiology essentials for non-audiologists, presented in partnership with RIT/National Technical Institute for the Deaf. Continued.com - SpeechPathology, Article 20736. Available at https://www.speechpathology.com/.