Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Intervening with Selective Mutism: The Nuts and Bolts of Behavioral Treatment, presented by Aimee Kotrba, Ph.D.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify the correct starting point and tool for intervention based on evaluation.

- Describe how to develop a communication ladder for shaping.

- List instructions for stimulus fading for school or clinic setting.

Introduction and Overview

Thank you for attending today's webinar on the intervention and treatment of selective mutism. To give you a bit of my background, I obtained my PhD in Michigan, after which I completed a practicum, an internship and my post doctoral research. It wasn't until I did my post doc, about ten years ago, that I heard the term selective mutism for the very first time. At that time, a young patient came into our hospital presenting with a severe case of selective mutism. A second grader, he had never spoken to anyone in public, had never spoken to anyone at school, and had stopped speaking to his parents about one year prior to that. Not knowing much about the disorder, I did some research on selective mutism, and I found that there wasn't a lot of existing literature on SM. I became highly interested in the topic. Behavioral intervention with this child was successful and beneficial, and I was capable of doing it.

As a result of that experience, I started seeing children with selective mutism. Now, our clinic sees a lot of children with SM, both from local areas as well as from around the nation. They enroll in what we call "intensives", which involves coming in to our clinic for one week and participating in 20 or 25 hours of behavioral intervention. I love seeing children with selective mutism, because I feel like the intervention makes sense and you can clearly see the gains that these children make. When they improve, it is very overt, and you can see them start talking to more people and gaining confidence. Hopefully, by the end of today's webinar, you can take away some intervention techniques to use with children with selective mutism in your particular work setting.

DSM-V Criteria for Selective Mutism

The DSM-V defines selective mutism as follows:

- Consistent, ongoing failure to speak in specific social situations

- Interferes with education or social communication

- Not due to lack of language skills

- Other disorders (e.g., stuttering, PDD) have been ruled out

- A relatively rare childhood disorder, affecting approximately 1% of children in elementary school settings

In my experience, children with SM have the greatest difficulty speaking at school, where there is a lot of social anxiety and social pressure occurring. School tends to be a "perfect storm" for children who struggle with SM. I would say that a typical presentation of selective mutism is a child who struggles to speak in school, struggles to speak in public situations, often struggles to speak with family, friends, or extended family members. This leads to interference with education and social communication.

Furthermore, the difficulty speaking is not due to a lack of language skills. However, if you attended my last webinar about assessing for selective mutism, you'll know that SM commonly co-occurs with language disorders. A diagnosis of SM can be made after other disorders (e.g., stuttering, PDD) have been ruled out.

Finally, selective mutism is relatively rare, occurring in about 1% of children in elementary school settings. To date, there have not been any comprehensive research studies to assess the prevalence of children experiencing this disorder. It does seem that the number of cases are growing, although that is likely due to increased awareness of SM and our improved ability to identify and treat the disorder.

Components of a Good Evaluation

A good selective mutism evaluation would include the Selective Mutism Questionnaire, which is the only questionnaire specific to selective mutism. In addition, you would want to know the background history of the child, and whether anxiety runs in the family (parental anxiety). You would also want to know the situations in which the child is currently speaking, and to whom they are speaking. Find out who they talk to in the school and where they talk, so that you'll know where to begin when you start intervening.

Conceptualizing Selective Mutism

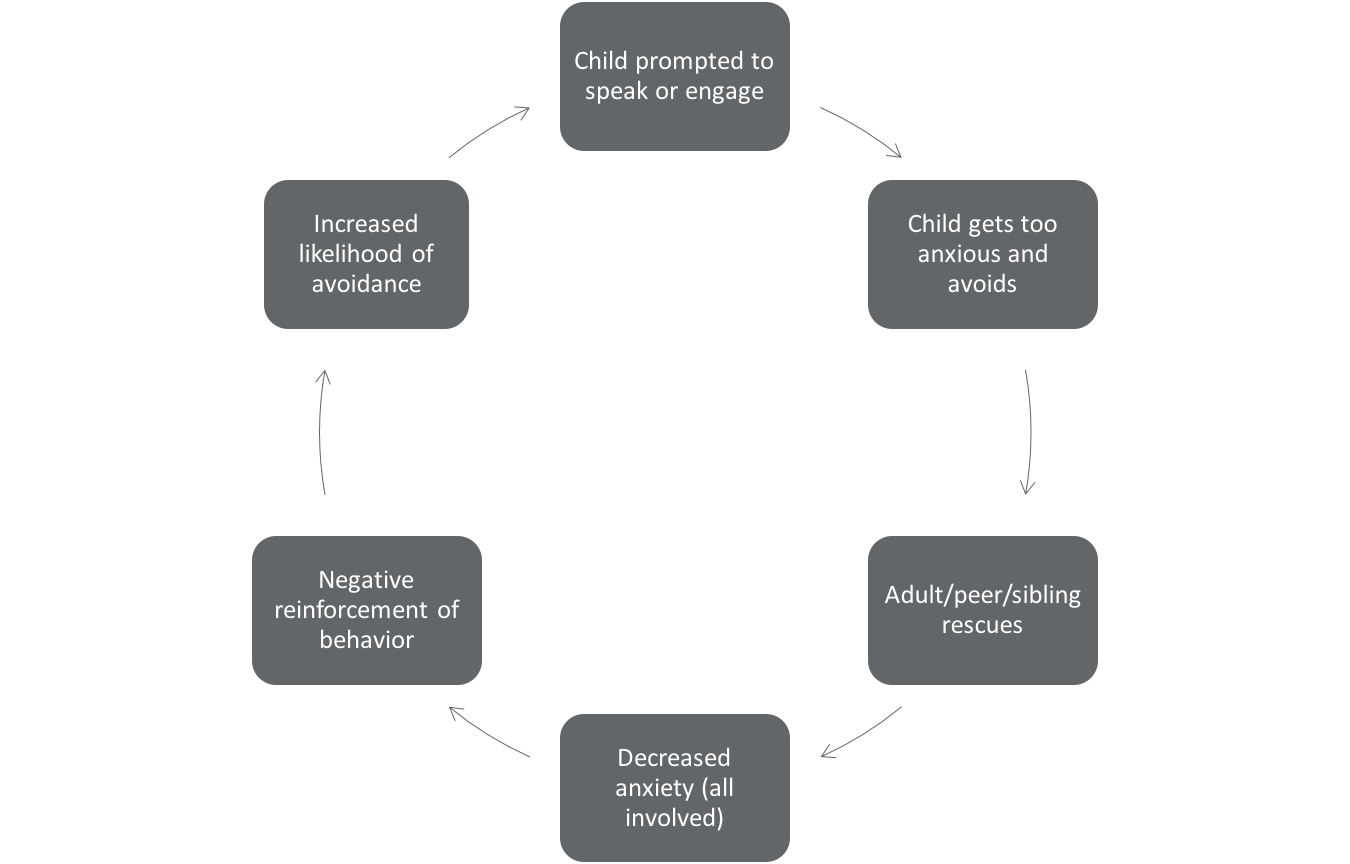

We conceptualize selective mutism as an anxiety disorder. These children are put into situations where they're prompted to speak or engage. Because they are biologically, neurochemically, or temperamentally anxious, they avoid these situations. This is normal human behavior. With any type of anxiety-provoking situation, in the moment or when thinking about that situation, our first thought is probably, "How do I get out of it?" For example, if we have a big presentation to give, or a review coming up at work, our natural instinct is to think about how we can escape the situation.

When children appear to be overtly anxious, someone often steps in and rescues them. Rescuing happens in a number of different ways. Sometimes, rescuing occurs by parents, siblings, or peers speaking for the child. For example, at a doctor appointment, the doctor may ask the child what grade they are in, and when the child looks uncomfortable, mom chimes in to say he's in third grade this year. Another way that rescuing occurs is that parents, peers, or siblings simply prompt or let others know not to even ask the child any questions. For instance, if a substitute teacher comes into the classroom, one of the child's friends will tell the teacher, "Miriam doesn't talk", alerting that person not to even ask questions of the child.

When people rescue, that decreases the anxiety of the child, because they don't have to face that scary situation. Rescuing also decreases the anxiety of the rescuer, because we don't like to see children struggle. It's uncomfortable for us, and we want to try to save them. Unfortunately, rescuing reinforces both behaviors: the behavior of rescuing, and the child's desire to avoid. Next time, the child is more likely to avoid situations where they're prompted to speak or engage, and other people around them are more likely to rescue, or even stop asking them questions altogether. We skip over them at circle time. We ask them only questions that they can nod or shake their head to. The longer this cycle of avoidance occurs, the more set in stone it becomes, the harder it is to intervene (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptualizing selective mutism.

Today, we're going to talk about a few different places today to intervene, because there is a better way to do this. There is a better way that includes the child being prompted to speak or engage. They get anxious, but instead of avoidance, we teach them other ways that they can deal with that anxiety. We try not to rescue as quickly. Instead, this changes the avoidance cycle into what you could call a "brave" cycle.

Choosing an Intervention

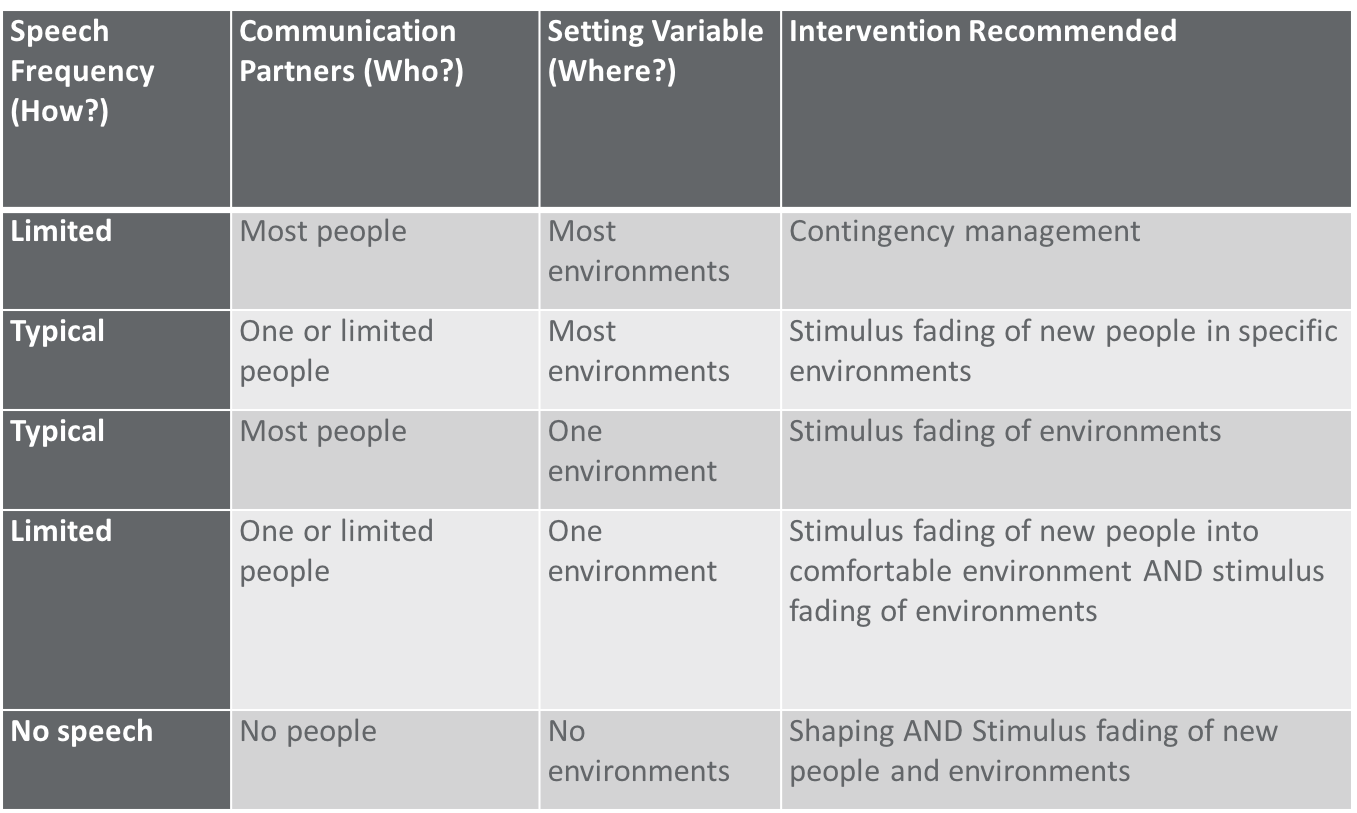

When choosing an intervention, there are several things to consider. We haven't discussed all of these different interventions yet, but I think that this chart will help you keep in mind what kind of intervention you should specifically pay attention to (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Choosing an intervention for selective mutism.

Looking at Figure 2, the first column is Speech Frequency (i.e., how much does the child talk). The next column is Communication Partners (i.e., how many people do they talk to). Next, is the Setting Variable (i.e., how many environments do they talk in). Finally, based on those first three criteria, the fourth column shows the intervention that's recommended (Shriver, 2011).

If you have a child who doesn't talk a lot, but does talk to most people in most environments, then you would use contingency management. You could think of this as a type of reward system, where speaking is highly rewarded, and not speaking is less rewarded, or less reinforced. In these mild cases of selective mutism, you really want to ramp up the reinforcement of speech.

You may have a child who does speak to only one or perhaps a handful of people outside of the home setting, but he will talk to those people in most environments. For example, as the child's SLP, they will talk to you but no one else at school, and they will talk to you in most places at the school. In those cases, you need to use something called stimulus fading (which we'll learn about in a few minutes). This is the idea of generalizing existing speech to new places or to new people. In this case, you would try to generalize that speech that you have to new people.

Another scenario is a child who has typical speech frequency with most people, but only in one environment. He'll talk to most people if they come into your office, but once you open that door to your office and step outside, he stops talking. In that situation, you're going to take that speech and generalize it to new environments.

If you have a child who has limited speech frequency to only one or a few people and only one or a few environments outside of the home, then you have to generalize speech to new people and new environments.

Finally, if you have a child who does not talk to anyone in any environments, you can't do stimulus fading. You can't generalize that speech to new environments and new people. Therefore, you have to start off with shaping, which is reinforcing successive approximations of speech. You must continue to use shaping of speech until you have speech, and then you can generalize that speech to new people and new environments.