Editor’s Note: This text is a transcript of the webinar, COVID-19 and Dysphagia: What we need to know, presented by Angela Mansolillo, MA, CCC-SLP, BCS-S.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the respiratory, neurological, and otolaryngological manifestations of COVID-19.

- Identify five potential causes of dysphagia in patients with COVID-19.

- Explain how to incorporate respiratory assessment into clinical assessment of swallow function.

Introduction

In this course, we are going to talk about COVID-19 and what that means in terms of swallowing functions and swallowing disorders. We are also going to discuss the respiratory, neurological, and otolaryngological manifestations of the virus and how those manifestations result in dysphagia. Finally, we will talk about how our assessment process needs to be varied in order to accommodate the distinct characteristics of COVID-19.

What is COVID-19?

COVID-19 is a novel strain of coronavirus. Coronaviruses have been around forever. We have all probably experienced coronaviruses more than once in our lives. They manifest typically in cold-like symptoms, upper respiratory infections, etc. But this one clearly is something more.

COVID-19 is most closely related to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) virus. It seems to gain entry to cells through the ACE2 cells, which are mostly in cardiopulmonary tissue. So, respiratory issues are very predominant. But this virus also seems to be able to enter through white blood cells and possibly through brain neurons as well. We'll talk about that in more detail later.

It infects the mucosa of the upper airway. It is highly contagious, spreading through droplets, contact, and aerosolized particles. We will talk about the aerosolization issue as we go through the course. Contact with contaminated surfaces also seems to be a method of transmission. However, scientists seem to be less concerned about that now than they were initially. There is conflicting information about how long the virus is actually able to live on surfaces. Not that we don't have to be careful about that.

The aerosolization seems to be the bigger problem. Aerosolization occurs when people speak, sing, sneeze, or cough. Given that, speech therapy does create some challenges as you would imagine. That aerosolization also occurs during aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs).

Symptoms

COVID-19 symptoms are typically mild. I researched some statistics right before this course and there are 104,172,916 cases worldwide as of February 2021. Of those, about 26 and a half million are in the U.S. So, the U.S. currently has had about a quarter of the total worldwide cases. The number of deaths worldwide is 2,255,423, so that's a little over a 2% death rate worldwide.

Deaths in the United States, of those 26 and a half million cases, is 447,715. That's a little less than 2%. So, we're doing a little bit better in terms of survival rates. We have a lot of cases, but we have better survival rates. About 2% of people with this infection die from it, which is a small percentage. However, the number of deaths is huge because the overall number of cases is so large. We are talking about hundreds of millions of people worldwide.

But the symptoms, typically, for the majority of cases are fairly mild:

- Fever

- Cough

- Dyspnea

- Sore throat

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

- Loss of taste, smell

- Muscle pain

- Headache

- Fatigue

There is a lot of upper respiratory infection, as well as GI issues with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea. The one we hear the most about is loss of taste or smell which seems to be the hallmark of this virus and is persistent in a lot of folks. Even after the other symptoms have cleared, folks are continuing to deal with that.

There are, however, more severe consequences of this virus for a lot of individuals:

- Pneumonia

- Severe muscle weakness

- ARDS; severe hypoxia

- Stroke

- Acute kidney injury, renal failure

- Encephalopathy

- Multi-organ failure

- And…Dysphagia

Early Data

Here is some of the first data that came out at the very start of the pandemic in the United States. This is some data that came out of New York City in April of 2020.

NYC Hospital Admissions:

- Fever (30.7%)

- Oxygen requirement at triage (27.8%)

- RR>24 bpm (17.3%)

- HR >100 bpm (43.1%)

- Oxygen saturation <90% (20.4%)

- Required invasive ventilation (12.2%)

- Required ICU level care (14.2%)

- Acute Kidney Injury (22.2%)

- Death (21% overall; 88.1% of those requiring invasive ventilation)

(Richardson et al, JAMA, April 2020)

As you can see, there are a lot of respiratory symptoms: oxygen requirement, elevated respiratory rates, low oxygen saturation rates, need for ventilation. But also, some kidney issues, and fever.

Aerosol-Generating Procedures (AGPs)

When patients have issues like pneumonia, and they need oxygen or invasive procedures like mechanical ventilation, there is the potential for the generation of aerosol. Oxygen therapies like high-flow nasal cannula, BiPAP, CPAP, and tracheostomy generate aerosolization into the air. The particles that contain the virus are then expelled into the air. Many of the procedures and treatments that SLPs do and respiratory therapists do to care for patients are aerosol-generating. We do speaking valve trials, trach occlusion trials, suctioning, laryngeal stoma, TEP management etc. All of those have the potential to generate aerosol that is containing the virus.

If you think about the practice of speech-language pathology, there are a number of other procedures that we do routinely, that are not technically considered aerosol-generating procedures but have the potential to generate aerosol and increase exposure. For example, the clinical swallow evaluation, especially if it includes cough assessment. If you're asking people to cough, or if they are coughing in the process of swallow trials, that generates aerosol. Instrumental assessments can cause the same issue as does expiratory muscle strength training. These routine procedures that are critical to the way we care for individuals with swallowing disorders have the potential to generate aerosols containing the virus.

Why Dysphagia

Having established that there's a risk for SLPs, let's discuss why dysphagia is occurring in patients with COVID-19. We're going to see that it's complicated. There's more than one mechanism for the dysphagia in folks with COVID-19.

- Sensory changes

- Neuronal injury

- Pneumonia

- Cytokine storm

- Proning

- Respiratory-Swallow Discoordination

- Respiratory Failure; Post-extubation dysphagia

- GI dysmotility?

Before discussing each of the above factors, let’s do a quick anatomy review. The nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) is the primary sensory processor. It brings sensory information to the brainstem in order to trigger the swallow response. The swallow response is dependent on that sensory input and changes based on that sensory input. Colder boluses, larger boluses, smaller boluses, carbonated boluses all have the potential to change the swallow output and to change that swallow response. Sensory input is critical.

The nucleus ambiguus (NA) sends information from the brainstem to innervate the muscles of the soft palate, the pharynx, the larynx, and the upper part of the esophagus. These tracks are critical for the transmission of information for swallow function. Additionally, the cranial nerves are critical for providing sensory input and motor output. I’m not going to spend a lot of time on this, you can do your own quick review of the cranial nerves. But the point that I'm leading up to is that the sensory nerve fibers, as part of the NTS, are critical for triggering the swallow response. Sensory input is important in terms of getting the swallow response triggered.

What's happening in COVID-19 patients? Remember, we said that the hallmark of this disease in many patients is impaired sensation, impaired taste, and impaired smell. Taste perception and the swallow response share pathways and sensory information is important for shaping the swallow response. What happens in patients with COVID who have impaired sensation? It seems to be impacting the ability to initiate a swallow response quickly, although not in all cases. I will be saying "not in all cases" a lot throughout this course because one of the things about this disease is how incredibly variable it is.

The moral of the story is we don't exactly know and can't really pinpoint the impact that these sensory changes are having on the swallow response. But there does seem to be some impact on some clients.

Taste and Smell

This issue of taste and smell loss that occurs so frequently in patients with COVID-19 appears to happen more frequently in younger patients with COVID-19, in female patients with COVID, and in patients who already had some allergic rhinitis.

Other Otolaryngological Manifestations

There are a number of other otolaryngological manifestations as well, with taste and smell loss being the most common. But patients also complain about sore throat, nasal congestion, irritated throat, tinnitus in some cases, voice impairments, and others. All of those can certainly contribute to general feelings of illness in folks for sure.

Neurological Manifestations

We also know that this virus has the potential to cause neurological injury. I remember back in March and April of 2020, having conversations in the rehab staff room about all of these patients we were seeing who had severe strokes. We hadn't seen this number of strokes in our area in a long time. They were younger people who didn't have a lot of comorbidities or history that would make you think they had a lot of risk factors, but they were negative for COVID-19. They had been negative on their initial COVID-19 test and so we didn’t think that there was a connection.

We were trying to figure out where all these patients were coming from, hypothesizing that maybe they were putting off medical care and not coming in because they were afraid to come to the hospital because of the COVID-19 exposure. We actually found out later that this was in fact COVID-19 related even though they were testing negative for COVID-19.

COVID-19 particles have been found in human brain neurons. How they're getting there is not exactly clear. One theory is that they're traveling along the vagus nerve. Another theory is that they are getting in through the olfactory bulb. Perhaps the leukocytes are carrying them into the brain. It's not exactly clear. But, we know that in some folks, the virus is getting into those brain cells and creating a number of neurological manifestations, including stroke, as well as vestibular problems and headaches.

Rarely, but occasionally, we have seen encephalitis and Guillain-Barre. It's sometimes related to the severity of the infection, but not always. Again, there is a lot of fluctuation. But for some folks, the virus is actually getting into the brain cells and so, we are dealing with patients who've had strokes, and in my experience, sometimes really severe strokes. The dysphagia, in part, is then related to that stroke.

COVID-19 Pneumonias

We also need to look at COVID-19 pneumonias. These are severe lung illnesses caused by the virus, they tend to be bilateral. If you look at the chest x-rays, they are dense with fluid. You almost don't have to be a radiologist to diagnose this. You look at these lungs and can see that there is no airspace.

On chest CTs, we can see significant ground glass opacities all through the lungs. Patients with COVID-19 pneumonia often have what's called silent hypoxia. So, their saturation levels are dropping, their O2 levels are low, but they're not experiencing significant dyspnea. Thus, oxygen saturation monitors are so critical for these folks because they're not necessarily going to be symptomatic.

Cytokine Release Syndrome

Another potential issue is Cytokine Release Syndrome. Cytokines are very small peptides that are produced by white blood cells. They're important for immune system functioning and in the presence of an infection, your immune system releases cytokines to help coordinate the immune response. When very high levels are released, it can create problems like drops in blood pressure and mental status changes, confusion, acute kidney injury, respiratory distress, multi-organ failure, and dysphagia as well.

What happens with cytokine release syndrome or "the cytokine storm", is that you're in the face of this virus and your immune system is essentially over-responding. The overall response of the immune system is creating additional problems for the individual, one of which might be dysphagia.

Kidney Connection

We know that there is an interrelationship between the kidneys and the lungs. In order for our bodies to do all the things they need to do, acids and bases throughout and across systems need to be in balance and there are a number of organ systems that contribute to maintaining that balance. The two systems that have primary responsibility for that homeostasis are the renal system (i.e., the kidneys) and the respiratory system (i.e., the lungs). The renal system contributes to homeostasis through waste management. The kidneys are part of your waste management system and they can either let go of those waste products or retain and recirculate them depending on what your body needs at the moment to stay in balance.

Your respiratory system contributes to this balance through the process of respiration, making sure that there's a balance between O2 and CO2 throughout and across the cells in your body. Your respiratory system and your renal system are actually working together to maintain that homeostasis. With COVID-19, sometimes one of those systems goes down.

For example, the respiratory system goes down because of COVID-19 pneumonia and that creates stress on the renal system because the renal system now has more responsibility for maintaining that homeostasis. Then we end up with some renal problems. Alternatively, the virus detects the renal system and that system goes down putting more stress on the respiratory system to maintain homeostasis. So, there is a fairly important connection between the respiratory system and the renal system. Again, the virus can attack one of those systems or sometimes both.

There's also something called Bradykinin Storm. These are peptides, like cytokines, that help to fight infection by promoting inflammation. In some COVID-19 patients, there is a flood of bradykinins into multiple systems that creates problems like arrhythmia, pulmonary edema, encephalopathy, myalgia, or ischemia. The COVID-19 virus seems to trigger an over-response, this hyperresponsiveness, within the immune system that creates a set of new problems for the individual.

Respiratory-Swallow Coordination

The bradykinin storm is thought to be the cause of the hydrogen that we see in the lungs. It's really this thick fluid that doesn't move, takes up airspace and makes it so difficult for folks to maintain oxygenation. Given that, another potential contributing factor for dysphagia in folks with COVID-19 is a discoordination in breathing-swallow functions.

We know how important breathing-swallow coordination is. When we talk about respiratory-swallow coordination, there are three components that we think about. One of those components is the respiratory-swallow pattern. The most typical pattern we know is: exhale a little, swallow, exhale some more. That post-swallow exhalation is so critical to swallow safety because it helps to clear out any pharyngeal residue, to facilitate vocal fold closure, and facilitate laryngeal valve closure.

The second component of breathing-swallowing coordination is lung volume initiation. In other words, what is the lung volume when the swallow is initiated? Most swallows tend to occur somewhere in the middle part of the lung range. You don't have to fill your lungs to capacity every time you take a sip of water. However, we also don't want to be in the low part of the lung range. Folks have to be able to at least get to the low middle to the middle part of the lung range in order to swallow safely. You have to have some air to get you through that period of respiratory pause.

The respiratory pause duration is the third component of breathing-swallow coordination. We stop breathing to swallow. The duration of the respiratory pause is about a second. If there is some dysfunction in respiration and you are air hungry, you will have shorter periods of respiratory pause and are more likely to demonstrate a possible inhalation.

Likewise, if you are struggling with pneumonia, you may not be able to get to the middle part of your lung range. So, these various underlying respiratory problems can create difficulty in any one of these components of breathing-swallow coordination. And breathing-swallow discoordination is likely to cause dysphagia. We know from other populations that when the respiratory system is compromised, there is breathing-swallow discoordination and that breathing-swallow discoordination causes dysphagia. There are a number of studies that indicate that, although none have been done with COVID-19 patients yet.

Impairments in respiratory-swallow coordination specifically result in increased pharyngeal transit times, pharyngeal residue, airway compromised penetration/aspiration, and delays in swallow initiation. When the respiratory system is off, then breathing-swallow coordination is off, and dysphagia is the result of that. So that's definitely a potential cause of dysphagia in our COVID-19 patients.

Proning

Another issue that may be contributing to dysphagia is a treatment strategy called proning. You may have patients at your hospital who have benefited from this technique and it is not unique to COVID-19. It's been used for years with patients with respiratory compromise but seems to be really effective for patients with COVID-19. So, we're seeing it being used much more routinely than we ever did before.

Proning is just what it sounds like. Patients spend a lot of time in the prone position (i.e. on their stomachs). The head is turned to one side or the other and one arm is over the head in what is called a swimmer's position. While they might maintain that prone position for 12-18 hours, their head position is changed routinely, about 1-2 hours depending on the protocol, and they alternate arms over their head as well.

In our hospital, this is utilized fairly routinely with COVID-19 patients who are ventilated, but, last summer, we also began using it fairly successfully with COVID-19 patients who were not ventilated. I think that's probably true in other facilities, they have probably had the same kinds of results.

Why does this help? It seems to take some of the pressure off the lungs. It takes the weight of the body and the weight of the abdominal organs off the lungs. It requires less pressure to keep those alveolar spaces open and available for gas exchange and seems to help with the drainage of fluid.

However, it does create some problems. It makes oral hygiene very difficult. It increases the likelihood of airway injury because patients now have to be turned and they're changing neck position fairly routinely. If you think about that with an intubated patient, there's more potential for airway injury. There's also potential for airway injury when patients are moved from supine to prone. It's done very carefully by a team all working together to keep all the tubes, drains, etc. in place. But in that movement, in that shift, there's always the potential for more airway injury.

We have seen patients with breakdown in facial tissue from being in the prone position. Some patients have had significant upper extremity weakness from having their arms over their heads. We have seen pressure injuries on their knees, breasts, orbital pressure issues, and in some cases vision loss. I have not seen a lot of that in our facility, but I've read that it is sometimes a problem with proning. However, we have seen a lot of oropharyngeal edema due to hyperextension of the neck.

While proning has been demonstrated to decrease mortality in COVID-19 patients, we do see more pressure sores and more difficulties with ET tubes. If you think about the potential for edema and the potential for airway injury, once these patients are extubated, the likelihood of post-extubation dysphagia is going to increase.

Respiratory Failure

Another contributing factor to dysphagia that we see in patients with COVID-19 is respiratory failure. These patients have a lot of fluid in their lungs and they're hypoxic. But in some cases, there might be some brain injury, some central nervous system dysregulation. All of this contributes to the respiratory failure that we see in these patients and may be the cause of recurrent respiratory failure.

These patients are recovering slowly. We are seeing a lot of back steps with patients who may be extubated, seem to be doing well, and end up in respiratory failure again. We are seeing that frequently. Recovery from COVID-19 is not a straight line.

Intubation Considerations

I am going to talk about the next two sections very briefly because there is actually another course specific to post-extubation dysphagia (Course 9653). We know that intubation is achieved through hyperextension of the head and neck, the airway is visualized, and the ET tube displaced. It is often done quickly and urgently, so there is certainly risk of laryngeal trauma.

Post-Extubation Considerations

We've already established that in COVID-19 patients who've been prone, there's potential additional airway injury because of the proning itself. Therefore, there are a lot of issues with post-extubation dysphagia in our COVID-19 patients. In some ways, the issues are similar to all of our other patients with respiratory disease, but in other ways, they are more complicated.

A number of contributing factors to dysphagia in this post-extubation population are:

- Residual effects of sedating meds; delirium; decreased level of alertness

- Alteration in airway sensitivity

- Potential for glottic injury (laryngeal injury)

- Disuse atrophy

- Weakness

- GERD secondary to medication, supine position, NG tube (reflux disease)

- Reduced breathing-swallow coordination

The question for COVID-19 patients and non-COVID-19 patients is always, “Once they have been extubated, when do we begin oral feeding?” We don't have data yet on COVID-19 patients but there is some data that was done pre-COVID. There's conflicting information in terms of whether or not these folks are ready for oral feeding and when they are ready for oral feeding. There are a number of factors that can potentially contribute to post-extubation dysphagia that we need to consider as we make the decision about whether or not to move forward with oral feeding.

According to the research, folks who are more likely to have dysphagia post-extubation include:

- ▪ Prolonged duration (>48 hours) of intubation*

- ▪ Age > 55

- ▪ Poor pre-morbid functional status

- ▪ Increased duration ICU stay

- ▪ Repeated intubations

- ▪ Upper GI dysfunction

- ▪ Kidney disease, CHF

- ▪ COVID; proning

Probably the biggest factor to pay attention to is the duration of the intubation. The longer the duration, the more likely it is that there will be some post-extubation dysphagia. Certainly, this is a big issue for our COVID-19 patients because they tend to have longer than typical periods of intubation.

GI Issues

If you've heard me speak before, you have probably heard me say that what happens in one part of the body impacts what happens in other parts of the body. There are very close connections between the GI system and the respiratory system and this is certainly true for our patients with COVID-19 as well. There is a lot of esophageal dysmotility and gastric dysmotility that is contributing to the respiratory distress. As a result, these patients are experiencing more reflux and aspirating that reflux. Even micro-respiration of acidic stomach contents can be problematic and detrimental to a long recovery.

As an aside, there is some evidence to suggest that patients taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be at higher risk for COVID-19. We know that proton pump inhibitors increase risk in a lot of areas and COVID-19 seems to be another one of those. As you may know, we need stomach acids to kill the bad bacteria. When we don't have sufficient amounts of stomach acids, that can be problematic for a number of reasons, including increased COVID risk.

I mentioned earlier that our patients with COVID-19 tend to have longer than typical periods of intubation. "Pre-pandemic" practice was to convert from ET tube to trach tube after a week or no more than two weeks. But we're seeing that conversion being postponed with patients with COVID-19 because of the potential for aerosol generation. We are seeing folks with long periods of intubation, and a lot of airway injury as a result. Some of the issues that are occurring as a result are:

- More laryngeal edema

- Laryngeal injuries

- Laryngo-tracheal stenosis (LTS)

- Granulomas

- Glottic webbing

In addition to all of the other considerations, when a COVID-19 patient has been extubated, you also want to think about all of their comorbidities, the disuse atrophy, and the impact of social isolation on these patients. Because visitors are currently not allowed in hospitals and long-term care facilities, social isolation can be a real contributing factor.

An interesting study was conducted comparing ICU patients who were COVID-19 positive to ICU patients who were not (Lima et al., 2020). They found that the COVID-19 patients had longer periods of intubation, and were more likely to have swallowing difficulty that was persistent. These folks had more significant dysphagia and were slower to recover.

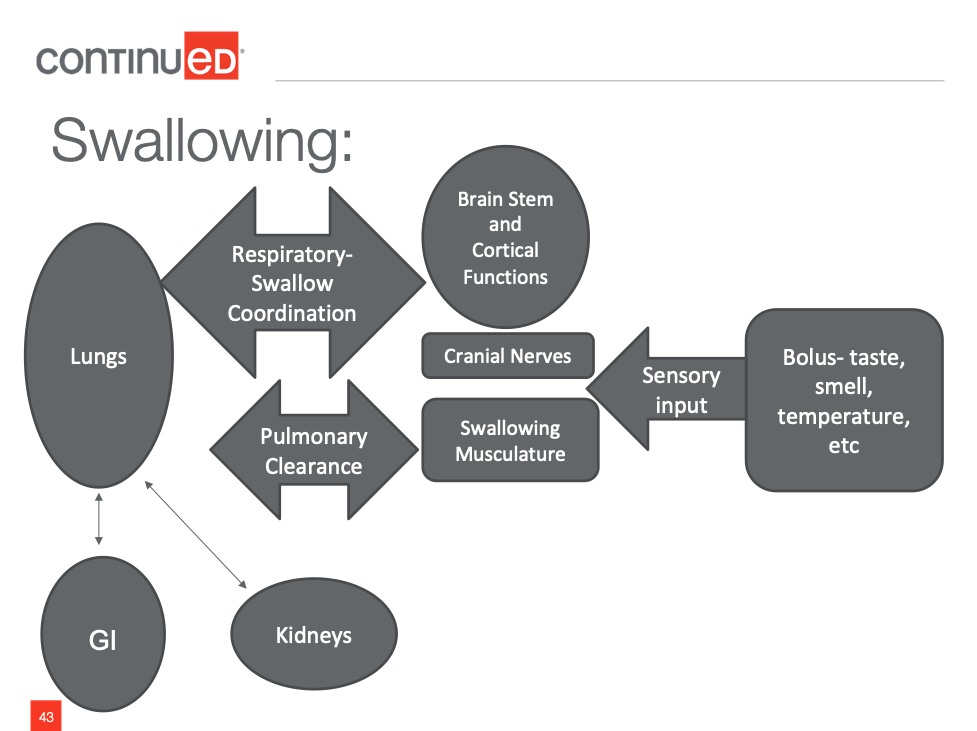

Swallowing

Putting all of this together, we know that swallowing is complicated. We know that it requires sensory input, that then triggers a swallow response that involves cortical functions, brainstem functions, cranial nerves and swallow musculature. We know that the swallow response has to be coordinated with respiration. So that means the lungs and the respiratory system are involved.

We know that the lungs also have a role to play in terms of pulmonary clearance if aspiration does occur. The GI system and the renal system are very much intertwined in terms of the response.

Figure 1. Swallowing is a complicated process.

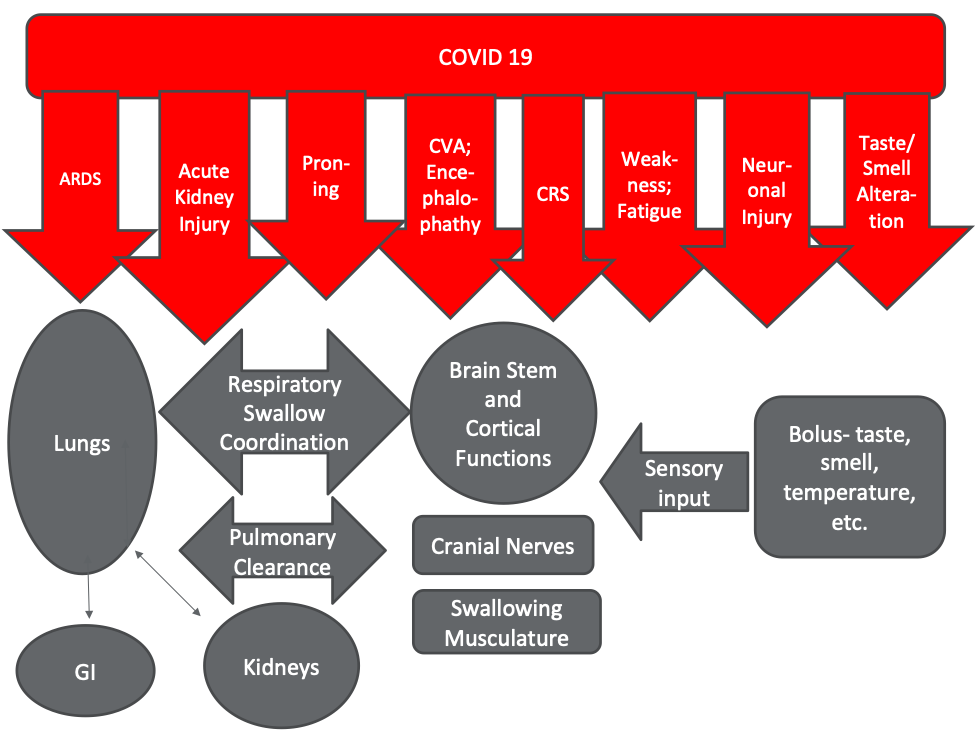

When we think about what happens with COVID-19, you can see all of the factors that we've been talking about have the potential to impact swallow function anywhere along the way. It’s not surprising that we see a lot of dysphagia in folks with COVID-19 for all of the reasons that we've been talking about.

Figure 2. Impact of COVID-19 on swallowing.

General Recommendations

How are we managing patients with COVID-19 and dysphagia? The following recommendations came out last summer (Vergara et al., 2020).

- Utilize appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- When in a patient's room, stand at the side of the bed; maintain distance (3-6 ft) whenever possible

- Avoid procedures, techniques that induce cough

- Limit intra-oral examination, laryngeal palpation, cervical auscultation

- Encourage self-feeding

- Gather as much info as possible BEFORE entering the room

- Use time efficiently (limit exams to 10-15 min)

Obviously, I don't need to tell you that we need to be protecting ourselves with appropriate PPE. When we're in patient rooms doing clinical swallow evals, try and maintain some distance, stand at the side of the bed, and try to avoid techniques that are going to induce a cough. I know that doing a swallow eval induces cough in some patients but I'm saying let's not test a voluntary cough. Let's not get right in the oral cavity. Let's get as much information as we can, while still protecting ourselves.

Encourage patients to self-feed as much as possible so that we can maintain some distance. Having said that, these patients, particularly newly extubated patients, are very weak and often have upper extremity weakness from proning. Therefore, sometimes there's just no way around it. We have to be close and we have to feed patients. Again, that means making sure that we have appropriate PPE.

Also, limit your time in the patient’s room by getting as much information from the nurse, the physician, or the medical record to minimize the time in the room, but maximize the way that you use the time in the room.

Acute Care Considerations

For those clinicians working in acute care settings, there are a couple of things that we have learned over the last year or so. If you didn't already have a protocol for identifying post-extubation dysphagia, you need one. You need to put a screening mechanism in place.

We have also gotten into the practice of placing an NG tube as part of the extubation process. What was happening was as the ET tube was removed, the feeding tube was often removed as well. But, we’re finding these patients are unable to maintain nutrition by mouth so we are then going back and placing the NG tube. This is being done a little more routinely when patients are extubated, particularly the patients who've had longer periods of intubation.

For a long time, we did not have access to instrumental assessment, and our access to instrumental assessment is fairly limited even now. So, we really have to hone our clinical assessment skills.

Most importantly, we have to expect fluctuations in performance. That's certainly true in ICU but with COVID-19 patients as well. They fluctuate considerably. It's helpful to provide nursing staff with some flexibility in terms of recommendations. For example, order trays that have pureed items and soft solid items because we don't know what patients are going to feel like at noontime when that tray comes up. Giving nursing staff some help in that way is important.

Swallow Screening

As I said, if you don't have a solid screening protocol in place, it's imperative to do that at this point with your COVID-19 patients. We need to be identifying these folks and getting as much information as possible before we go into the room. The swallow screening is an important part of this process. There are a number of types of screening tools. There's another course that I presented on swallow screening that takes a close look at all of the screening tools (Course 9210). Remember, if you're doing water screening or cough testing as part of your screening tool, there's going to be the potential for aerosol generation. We need to protect ourselves with appropriate PPE.

Clinical Assessment

When doing your clinical assessment, watch for breathing-swallow coordination or lack thereof. Watch for changes in respiratory rate and fluctuations in level of alertness. Incorporate some type of cognitive screen because there's often some cognitive impairment and mental status changes with these patients.

There is some data from other patient populations with respiratory compromise, that give some insight in terms of what we should be looking for during our clinical evaluation (Steele and Cichero, 2014):

- Respiratory rate that's upwards of 25 breaths per minute

- Deterioration in breathing-swallow coordination

- Low baseline oxygen saturation levels (<94%) - not fluctuations in oxygen saturation throughout the assessment but that baseline level gives some insight into whether or not there's a risk for aspiration.

- Inconsistencies in breathing-swallow coordination - particularly that post-swallow pattern.

- Are you seeing a post-swallow inhalation - when are you seeing it? Are you seeing it all the time? Are you seeing it with solids and not with liquids? Are you seeing it toward the end of your trials?

Again, these are some factors that we know to pay attention to from other populations with respiratory compromise.

Aspiration Assessment - Respiration

As you're doing your clinical assessment, watch respiratory rate. What is the rate when you start? What happens to it as you start to impose the demands of swallowing on the respiratory system, that repeated breath-holding, repeated swallow apnea.

Watch the depth of the respiration. Remember that you have to get to the middle part of the lung range to swallow safely. Is this someone who's breathing more shallowly and probably isn't getting to the middle part of the lung range? Do they not have sufficient lung volume to get them through that period of swallow apnea?

Watch the coordination and the post-swallow pattern. Look at it across bolus type and size. We're looking for dyspnea and increased work of breathing during speech and swallowing tasks. During swallowing tasks, you're looking for reliance on the accessory muscles, that shallow sort of breathing and increase in respiratory rate. The patient might also be able to tell you, “I just feel short of breath. I feel like I can't breathe. I feel like I can't get air in my lungs.” These are all important signs to pay attention to as you're doing your clinical assessment.

In recently extubated patients, there's a risk for vocal fold paralysis, laryngeal edema, and decreased sensation. This is complicated by mental status changes and disuse atrophy, particularly in folks who were intubated for longer periods of time. Some of these airway injuries appear to be even more pronounced if a patient spent a lot of time in the prone position.

Post-Acute Considerations

Once these patients are out of acute care, they often continue to have prolonged periods of muscle weakness and persistent swallow problems. They're going to need ongoing management. They're going to need help with energy conservation. They will need diet modifications and some flexibility in those modifications because there are going to be days when they feel pretty good and days when they don’t. There are going to be parts of the day where they feel like they can eat a whole meal and other parts of the day where it's just too hard and they only want a milkshake or a supplement. So, we need to build that flexibility into our management of these clients once they leave acute care.

Ambulatory Patient Setting Considerations

If you're working in an ambulatory setting, you still need PPE. You want to think about your physical environment and make sure that you have the space to be able to maintain some distance while doing your assessment and your treatment.

That may mean limiting family members and, unfortunately, limiting students. You should probably have a COVID-19 screening process in place in your outpatient setting, which I'm sure most of you do at this point.

Long-Term Care Considerations

In long-term care, access to instrumental assessment is even more limited than it was prior to COVID-19. Again, we need to make sure that we have appropriate PPE. We also need to be on the lookout for the impacts of social isolation and observing folks who are eating by themselves because family members can't come in and check on them as often. We should have a process for keeping track of folks so that they're not slipping through the cracks. We need to have a process for identifying fluctuations in performance in these folks.

Diet Modifications

In terms of dietary modifications, we've been using texture modifications a lot, mostly because of fatigue. But as I said previously, have some flexibility built in so that patients have the ability to choose a higher texture item if they're feeling pretty good that day.

We have been very cautious at my facility. We're always cautious, but we have been very, very cautious about using thick liquids with our COVID-19 patients because they fluctuate so much. It's just so hard to be sure that the thick liquid is going to do what you need it to do. If you put this recommendation into place, and they're worse this afternoon than when you saw them in the morning, and they aspirate that thick liquid, now they're in worse shape. Therefore, we've been using a lot of water protocols and ice chip protocols with these patients because the risk of aspirating the thick liquid is really high in these patients.

This recommendation is based only on my experience. We don't have any research yet on water protocols with COVID-19 patients. But we have been using water sips and ice chips a lot with these folks and trying to hold off on the thick liquids as much as we can because we don't want them to aspirate the thick liquid.

Given these fluctuations in performance, it's hard to be sure that the intervention is going to work every time. We've had some success with cold boluses for some patients, but other patients actually prefer warm. So, that's going to be a personal preference.

Again, build in that flexibility. Patients are going to need options at each meal depending on how they're feeling that day. Similar to other patients, if they want to get better at swallowing, they have to swallow. These are often patients who've had prolonged periods of disuse and significant disuse atrophy. Giving them some opportunities to practice with swallowing is beneficial. Water sips throughout the day, ice chips throughout the day, and regular oral care are all stimulatory and can reduce disuse atrophy.

Compensatory Strategies

Probably the most important compensatory strategy is to slow down. We want patients to decrease the demand and take breaks. Conserve energy for mealtimes. For example, have the patient take a small sip and then put the cup aside or take a few bites, and then have a little bit more later. These folks are exhausted, so we need to make sure that the pace is slow enough for them. Smaller bites and smaller sips tend to be helpful.

I've spent a lot of time talking to patients about the bolus-hold technique. I tell them that if they are feeling short of breath, take a sip and hold it for a second. Let your breathing regulate and then swallow. Chew up a sandwich or take a bite of pudding, but don't feel like you need to swallow it right away. Just hold on to it for a second, let your breathing regulate, and then swallow. This seems to be a good strategy for patients who are cognitively intact.

Case Review

Let's finish up with a case review. This is actually my very first, but certainly not my last, patient with COVID-19. It was a scary time for all of us. This woman was a lovely 72-year-old retired pediatrician. She had been physically active and physically fit. She was not your "typical" COVID-19 ICU patient. She had no comorbidities and no underlying lung disease. She was a pretty healthy 72-year-old when she got sick. She was admitted with increasing dyspnea. They tried BiPAP, but it didn't work and she was intubated. She spent eight or nine days intubated and was prone for significant periods of the day. She was extubated, as I said, on day nine, and failed her swallow screen (we use a water swallow protocol at my hospital). Like most post-extubation patients at the hospital, she got orders for OT, PT, speech and swallow.

When I first saw her, she was using high flow nasal cannula (HFNC). I think it was maybe 25 or 30 liters per minute. She was awake and she was weak. She said her throat hurt really badly and she was coughing. She was actually hoarse. When she would cough, she would try and lift her hand to her mouth and couldn't even do that. She just could not move. She was so weak and so tired, and certainly couldn't self-feed. She was clearly going to be unable to maintain nutrition. In those early days, we were still trying to figuring this out. Her OG tube had been pulled and they ended up placing an NG.

After that initial eval, she couldn't do significant amounts of anything. But we were doing water sips and ice chips throughout the day when she was awake and alert, which was increasingly longer periods of the day. We saw her daily for re-evaluations as is our protocol in the ICU. She was able to do increasing volumes very slowly. She transitioned to puree, and cold purees actually seemed to work best for her and were more appetizing to her. But her progress was certainly not a straight line. We adjusted her diet back and forth countless number of times. She would move from puree to ground and then she'd have a day where she'd have to go back to puree.

Again, there was constant accommodation as her status fluctuated. She did well. Despite those fluctuations, she moved to a step-down unit and eventually to our med-surg COVID unit. Her oxygen needs continued to fluctuate and her volume of intake continued to fluctuate. But she was discharged home on a modified diet. She had success with softer foods and was doing liquid supplements. She was drinking milkshakes and that type of thing on those days when liquids were just easier for her to manage.

What We’ve Learned

This is what we've learned so far. Recovery is not a straight line. There are a lot of fluctuations in performance. Therefore, we need to keep our diet recommendations flexible in that regard, as I've said multiple times.

More seriously ill COVID-19 patients are probably going to need some non-oral supplementation. We also have to think about the duration of the intubation which is sometimes prolonged in these patients. That's going to result in more compromised airways and longer periods of recovery.

Of course, there is still a lot we don’t know. We still have quite a bit to learn about these patients and the virus.

Questions and Answers

I have a patient who has macroglossia. I assume this is an acquired type of macroglossia where there's some inflammation of the tongue that has not resolved 11 months after coma. The tongue is protruding outside of his or her mouth five inches. This is a patient who had COVID-19. I am wondering about any medications that she might be taking that might be exacerbating that?

I know that sometimes psych meds or anticholinergics sometimes have the potential to exacerbate that. So I might have the physician or the pharmacist take a look at his/her meds to see if there's anything that's prolonging that recovery.

We see patients who frequently have arytenoid dislocation, but there is no ENT consultation available until the post-acute stage and after the patient is already gone. How would you handle that? Their dysphagia is obviously persistent.

We have the same issue. We have difficulty getting ENT consults in our acute care, critical care unit, for any number of reasons, not the least of which is that we have a physician shortage in Western Massachusetts. So, I hear you. What we have been doing is trying to put compensatory strategies in place, which is probably what you are already doing. We are just putting a safety net underneath them until they can see an ENT. In some cases, though, some of our intensivists and our pulmonologists have been willing to take a look at them. They can't provide the same sort of information that an ENT can, but they've been able to provide us with a little bit of information in some cases.

You were talking about how the assessments may be 10-15 minutes long because they get tired easily within 30 minutes. Why wouldn’t you want to assess them when they're at their worst stage to see what the worst-case scenario looks like?

Actually, I think that you would want to do that. I think regardless of when you're in there, you just have to recognize that that's probably not going to be truly representative. There'll be times after you leave when they're better and times after you leave when they're worse. And sometimes we don't have a lot of control over when we can get in there. We can get in there when we can get in there or when everybody else is not in there or when they're awake. The other issue related to timing is we get an order for patients who've been intubated. The extubation order in our critical care unit is linked to a swallow eval order. So, we get ordered in immediately. But sometimes we'll go up and the nurse will say, “Whoa, not yet. He's not ready yet.” So, we get waved off. Sometimes we'll take a look at the medical record or look at the oxygen requirements and decide that we're not going in there yet. But we get called and we get that referral right away and that's just part of our protocol.

How do we explain the increased risk of aspiration to RNs and MDs for those patients who are on high-flow nasal cannula or oxidizers? We get lots of referrals for these patients especially.

Yes. So, there is some research, some of which I included in the reference list. There's not a ton of research, but there's a slowly growing body of research to support aspiration with risking patients with some of those interventions. So that might be research that you could share with your team and I'm happy to provide you with more of the data if you email me directly.

Have you ever had experience with the use of carbonated cold beverages versus thickening with any benefit for COVID or other post-extubation?

Yeah, we use carbonation quite a bit, and that's been true for some of our COVID patients as well. There is research to support the use of carbonation as a way of improving the timing of the swallow response for sure, and so we do use carbonation. I will tell you that some of the COVID patients find the carbonation distasteful or unpleasant. Again, there is a lot of variability because there's a lot of variability in terms of their sensory changes. Just keep in mind that some COVID patients might not like the feel of it.

How valid do you think the results of MBS or VFSS might be given all the fluctuation in the patient's status? What kind of advice could you give for people who are having to kind of shift away from the instrumental exams and back to more clinical type assessments just because of the whole situation?

I do think that, obviously, there's value to instrumental assessment. If we want to know definitively what's happening in the pharynx or if we want to know the cause of the aspiration from a physiological perspective - Is it delay swallow response? Is it incomplete laryngeal valve closure? Is it pharyngeal residue because of reduced pharyngeal stripping? If we want to know specifically what the physiological cause is, then we need instrumental assessment. But we always recognize that it's not representative of everything this client can do or will do. That it needs to be put in the context of everything else we know about this patient, including our clinical exam. For patients who are acutely ill, and I think particularly for COVID patients with the fluctuations that we see, I'm not sure that it's going to give us the same kind of value. So, we are in fact, more dependent on our clinical evaluation. And the thing that will help to make our clinical evaluations as reliable and valid as possible, is a focus on those respiratory indicators that I talked about earlier. There's data that says, these are the things, the respiratory rates, over 25 breaths per minute, then the likelihood that the patient's aspirating increases. If the baseline oxygen saturation is below 94%, then we know that the aspiration risk increases dramatically, right? So those respiratory indicators are the important things to pay attention to in order to make our clinical evaluation more valid.

With prone positioning and patients laying on their bellies all the time, what effects does that have on the GI system? How do you feed them when they're in that position?

Proning does increase the reflux risk potential particularly in patients who have GERD. So, we do know that that's a risk. What we've been doing is to elevate the bed a little bit. Obviously, we don't want them sliding down. It's a fine line, right? We don’t want the patients crumpled at the bottom of the bed, but putting the bed on an angle to help with that a bit, even in the prone position. In terms of eating, we're not doing oral feeding in prone, so it's not oral feeding.

My question relates to nursing doing the water screens and how they don't often notice when patients are aphonic or have severely altered phonation after intubation. It seems that it is contributing to aspiration pneumonia on top of COVID pneumonia. Any comments on that?

Well, that's always a risk, right? With nursing administered screens, it's a constant education process. We spend our careers educating and re-educating people. That's not an issue specific to COVID as you pointed out with your question. There is research for the three-ounce water test, specific to the Yale swallow screen that demonstrated that it is pretty good at identifying patients who would otherwise be silent aspirators. It’s the volume and the repeated swallows that are done without stopping. Those things combined seem to help tease out those folks who would otherwise be silent aspirators. They may silently aspirate if you give them a sip or two. But, if you give three ounces of water without stopping, they're going to have to stop or they're going to cough, or there's going to be some overt sign of aspiration.

So, the three-ounce water test actually is pretty good at identifying those patients who would otherwise be silent aspirators. The issue of nursing administration, that's an education issue and it's just constant re-education.

Citation

Mansolillo, A. (2021). COVID-19 and Dysphagia: What We Need to Know. SpeechPathology.com, Article 20443. Available from www.speechpathology.com